How Does a Debate Moderator Work?

Read what Slate culture writer Aisha Harris asked Intelligence Squared U.S. moderator Jon Donvan about successful debates, good questions, and the art of interruption.

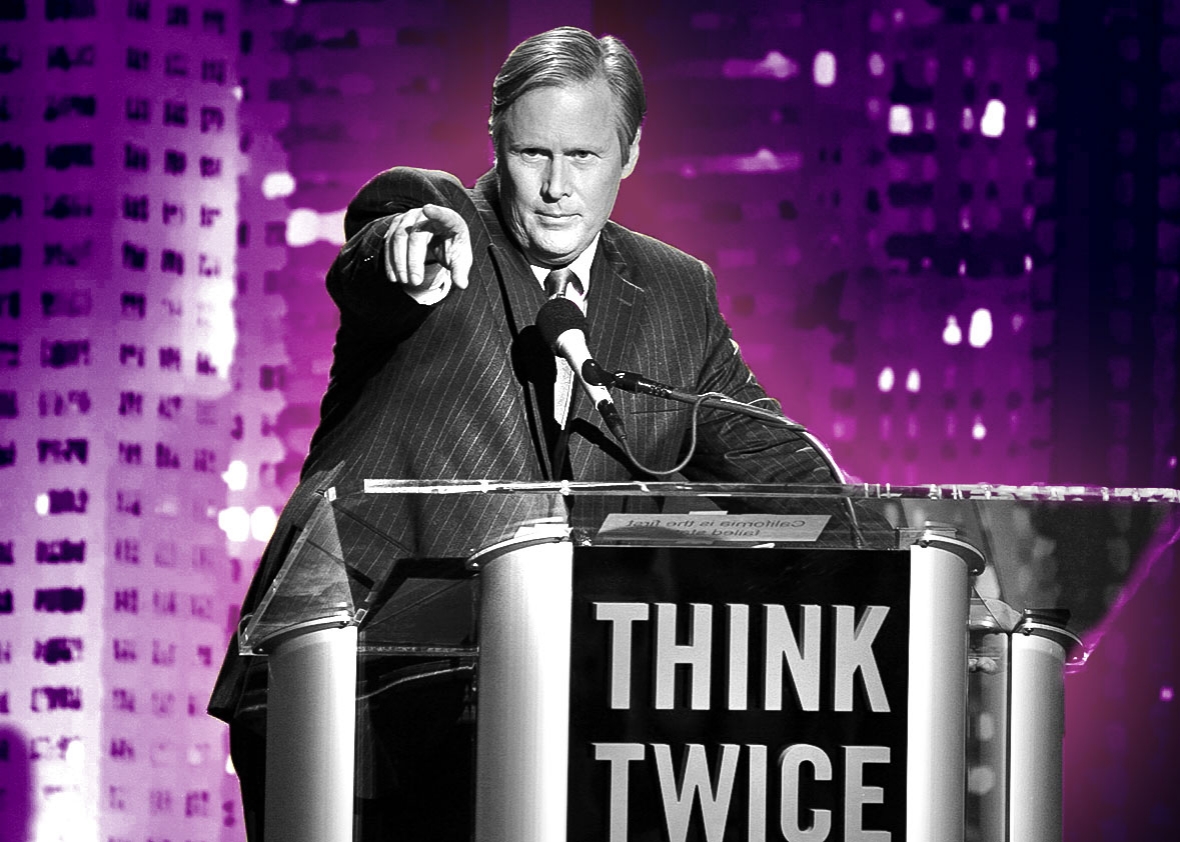

Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Intelligence Squared U.S.

We’re posting transcripts of Working, Slate’s podcast about what people do all day, exclusively for Slate Plus members. What follows is the transcript for Season 3, Episode 4, in which Slate culture writer Aisha Harris talks to John Donvan of Intelligence Squared U.S., a series of Oxford-style debates on the most controversial issues of the day. In this podcast, Donvan, who is a veteran ABC News correspondent, discusses why successful debates start with good questions and why a moderator must learn the art of interruption. Plus—Donvan schools Harris on why she shouldn’t try to game Intelligence Squared’s scoring system, for the Slate Plus bonus segment. To learn more about Working, click here.

We’re a little delayed in posting this episode’s transcript—apologies. This is a lightly edited transcript and may differ slightly from the edited podcast.

Aisha Harris: Welcome to Working, Slate’s podcast about what people do all day. I’m Aisha Harris, a culture writer at Slate. Today, someone who has made a career out of staying calm and staying on topic.

What’s your name, and what do you do?

John Donvan: My name is John Donvan, and I moderate debates.

Harris: And, where do you work?

Donvan: I moderate debates for an organization called Intelligent Squared U.S., which is based in New York City.

But, we take the debates a lot of places, many of them here in New York. But we’ve done them also in Chicago and in Boston and in Aspen, Colorado, and in Los Angeles, and in Philadelphia.

Harris: Can you describe to me a little bit about what the Oxford debate style is?

Donvan: The Oxford debate style is a debate where a proposition is put before the debaters.

A statement is made. It’s sometimes called a resolution. And it could be, for example, all people should eat eggs for breakfast. And two teams will debate for and against that motion. They’ll try to persuade the audience that indeed all eggs should be eaten for breakfast and that the resolution should be passed. Or, the other side is arguing that that’s wrong and that eggs should not be eaten for breakfast, or at least it cannot be said that all eggs must be eaten for breakfast.

And so, that’s the core idea, is that there’s this statement with an argument for and an argument against. And generally speaking also an Oxford-style debate has a structure. There are timed rounds, and the debaters have specific times in which they’re allowed to speak without interruption. And then they are allowed to speak and interrupt each other. And then normally there’s a final round in which they have a summarizing position. So, it lasts a limited amount of time.

And it really has that structure about being yes or no about the one question before the house.

Harris: Can you give me an example of a recent debate and just kind of the question or the statement that was put forward and then how they go back and forth, just to give the listeners an idea about how exactly it works?

Donvan: Sure. There was a debate we did in the early winter of 2015 where the motion was Amazon is good for readers.

And we had one team arguing for the motion and one team arguing against the motion. We had an author on each-—we actually had writers on all sides. Two of them were published authors, however. One was self published and loved the fact that he could self-publish with the support of Amazon. And the other was more traditionally published, and he was really bothered by the fact that Amazon had been taking over the book business, basically, in ways that he found really threatening.

And so, the two teams got up there, and they argued—they made arguments more or less from the point of view of the readers and also from authors and in the broad sense an argument about literature in general and whether the move to—the restructuring of the business as Amazon has affected it was good for all of those things. And so, arguments were made about the economics of the business, about the quality of editing, about the quality of literature, about book writing as an essentially entrepreneurial enterprise needing funding.

And some—there was an argument made that traditional publishing is the funding source for entrepreneurs who are called writers. And the other side argued that publishing houses were actually stifling entrepreneurialship among authors. And that was basically how it went on for about—we debate for about an hour and 45 minutes. And what we also do at Intelligence Squared U.S. is we have the audience vote on which side argued the best.

And the way we do that is we have everybody in the room vote before they hear the arguments. And then they vote again after they hear the arguments. And we give victory to the side whose numbers have changed the most between the two votes in percentage point terms.

Harris: So, I’ve actually been to quite a few of these debates, the ones that have been held in New York over the last couple of years. And one of the things that I always want to know is, so, for the Amazon one you had publishers and people who were self publishers.

What part do you play in deciding, A, what the topic is and, B, who you’re going to choose to debate these things?

Donvan: It’s a long process, actually, and sometimes a process of six to eight months to get a debate together from sort of germ of the idea to the night that we do the debate. And we’ll go down a list of ideas that are sort of out in the culture or in the news or perhaps are sort of eternal as well, and ask ourselves, first of all, is there something fresh to be said about the question or the topic?

And, is there really an argument there? Is there really a strong dichotomy of interest between two sides where there’s a zero-sum argument to be had, or almost zero-sum, between a for side and against side on a motion. And what would that motion be? And this list of ideas comes—it comes from us. It comes from listeners to our podcast or to our radio broadcast.

It comes from—we have board members. We get them by email. People have Tweeted us suggestions. And so, we start with a broad ocean of ideas. And then, every quarter or so we narrow it down to about 20. And then we investigate whether, in fact, there’s an argument there. Lia Matthow and Kris Kamikawa are the two members of our team who focus most on this. They’ll start reading to see, again, is the debate fresh or new? But is there really, really a debate there?

In other words, is there an argument to be had as opposed to something that’s just darn interesting. And often those two things don’t go together. And, after a while we’ll narrow the list down to maybe 15. And then we start framing motions, by which I mean we pick the language. Here’s a statement that, you know, one side could argue for and one side could argue against. And then at that point the very tricky part becomes, well, who are we going to book?

And what we look for are people who are already usually well-established in the field but more importantly well established in a way that they are identified with the side that they’re going to be arguing. So that generally speaking means people who have written about the issue before. Maybe they’ve written some of the things that we’ve been researching. And then we call them. You know, eventually we’ll get an anchor debater, somebody who says yes.

And then we will ask that debater, “Who would you recommend for a partner?” Because we always have two members on one side and two members on the other. It’s always two against two. Who would you want as a partner? And who is your worst nightmare as an adversary? And, assuming that they’re honest about that, we take a list of names. And we’re collecting lists of names from other people. And then we go to the other side, and we start calling them and saying, “Would you be willing to get on the stage and debate with somebody who disagrees with you viscerally about something that you care about?” And it’s a long, slow process.

Harris: Can you give me an example of a motion that you kind of regret the way it was framed?

Donvan: We did a debate where the motion was, “When it comes to politics, the Internet is closing our minds.” And what we really wanted the motion to be is, “The Internet is closing our minds.” And it turned out that that was not something that any side really wanted to argue because no side felt that, bottom line, literally, the Internet is closing our minds, period, because not when it comes to science, and not when it comes to education.

There were so many exceptions that we couldn’t find anybody really to argue against it. And when we explained, well, we’re really talking about what it’s doing to the political discourse, they said, “I get that, but that’s not what the motion says.” And so, we added on this clause. “When it comes to politics, the Internet is closing our minds.” And not only was it kind of an awkward phrase, but it became unclear in the course of the debate what it actually means, “when it comes to politics.”

And, it was one of those debates where the debaters end up arguing about what the motion means, which is not what the audience comes to be—you know, have that experience of that light bulb going off. They weren’t there to hear an argument about the meaning of the text that we put before them. They were there to sort of learn what two teams of smart people had to say about the impact of the Internet on the political discourse. And we didn’t really get there.

Harris: Let’s jump into what it’s like for you actually while you’re in the middle of the debate and being the moderator.

My first question would be how—you have a lot of experience. You were a longtime ABC correspondent. So you’re obviously very knowledgeable about things going on in the world. I’m curious. How much prep do you do beforehand? And how does that kind of help you navigate the debates that are going on onstage in that moment?

Donvan: Well, I worked for ABC, and still do, for a long, long time. And in that course of time I’ve basically done every story at least two or three times that’s out there.

I worked overseas in overseas bureaus. I was a White House correspondent. I covered the United States, you know, for years, from the point of view of economy, society, culture. I’ve reported on poverty. I’ve reported on race. I’ve reported on sports. I’ve reported on fashion. I’ve kind of—I was general assignment except when I was a foreign correspondent. I was general assignment. I feel like I’ve kind of done everything. And so there’s almost—there really is no topic that we debate that scares me into thinking, oh my gosh, I have no idea what this is about.

So, I have a—you know, it’s like a perfect chance to bring everything I’ve ever done into focus in this one, you know, this hour and 45 minutes, in a really useful and intelligent way—I hope intelligent way.

That said, I do a lot of preparation for each debate. Partly what I prepare on is the personalities of the debaters themselves. We’re going to have four people onstage. They’re all different from one another.

And I need to shepherd them through an hour and 45 minutes of keeping on point. And so, I watch everybody on YouTube, or a number of people that we come to come from think tanks, and the think tanks are always posting videos of them. And I watch them just to sort of get, like, their rhythms down, you know, so I know when they’re going to start talking and when they’re going to stop talking. And I know who’s a little bit nervous and who’s not and who’s reticent and who’s not and who needs to be pushed around a little bit and who doesn’t.

So, I watch them. And then I also—even though I’m not scared by any of the topics, I still read into—I read what they’ve written most recently. I back myself up with, you know, data, statistics, polls, to some degree studies on the topic that have been done before. So I feel like I want to go in there and not really be unbelievably surprised by any direction that anything takes.

So, I probably spend, you know, in the week before a debate, probably 25 hours or so of getting ready for it in that way. And then, before the debate itself, Donna Wolf, the executive producer, and I get on the phone with each team separately. And I and she—she walks them through what the format is. She tells them how the timing works and where to come. And she urges everybody please not to read a speech.

But then I give a talk about—I talk to them for about 15 minutes a little speech that I’ve prepared that’s about how to get in the spirit of what it is that we’re doing on the stage, that—to really get into the idea, number one, that it really is a contest, that they’re really there to—I wake them up to the fact that they may lose and that they should try to win and that they should try to show the audience that they want to win, and they should try to show the audience that they’re taking the exercise seriously. And what that exercise is is actually to enlighten people about their ideas.

And it’s not—you know, I use this phrase a lot in these calls. This is not CNN Crossfire. It’s not about trying to put down the other side. It’s not about trying to score points against the Democrats. It’s not about trying to score points against the Republicans. But the audience really, really wants to hear how they think about things and to be persuaded to think the same way if possible or to pick up a little bit of that. And, I tell them that they should function as a team, that they should really prepare, that they should study what their opponents have been writing about these things, that they should try to stay a few chess moves ahead of their opponents or anticipate where they’re going to go.

And I also tell them I’m going to be interrupting you a lot. And I say, “My apologies in advance, but that’s something I’m going to have to do.”

Harris: Right. That seems to be a big part of your job, which is timing is a huge aspect of the debates. And I’ve seen debates where people, debaters want to keep talking and keep talking. And you’re ringing the bell. You have a bell, correct? I think you have a bell.

Donvan: We just started with the bell this season. That’s a one—in each debate we do a thing that we call the volley round where we take one point and say, “OK, for two minutes we’re going to cover this point in two minutes. You each get 30 seconds, and the bell rings at the end of the 30 seconds.” So, that’s a new device.

Harris: So, how do you do that? Like, how—because when you have someone who just keeps talking, you—

Donvan: I just don’t let them. I have to say, I think that people, other people who have started moderating debates have called me and asked for tips.

And I say that for me the art of it—and it is kind of an art because it’s different every time. And I feel like I’m still learning it and getting better and better at it but still learning it. It’s a combination of extremely intense listening to what’s going on. And does this—is this guy on point? Is she making sense? Are people following her or him? Did that person just use language that nobody here will understand and I have to interrupt and ask for clarification?

Is this person missing the question? Is this person wasting our time? Is this person saying the same thing over and over again? And so, I’m listening very, very closely. And even though an hour and 45 minutes sounds like a long time, it’s actually not a long time to keep a debate moving along because we learned this early. If we let somebody keep talking for five minutes, then the other side in fairness needs to get five minutes.

And if the first side wants to rebut that side for five minutes and the other side gets to rebut the point for five minutes, 20 minutes have gone by on one little point which may not be even that interesting a point. And so, I’ve learned to very, very, in a way that’s not at all confrontational, interrupt. And that’s the other part of this secret, if there is one. It’s the art of extremely close listening, and it’s the art of interruption.

It’s not being afraid to interrupt, and I’m not. And it’s being able to sort of find the right moment to interrupt. The very best moment is when somebody’s taking a breath in, when they’re—you know, a period at the end of a sentence and ideally the end of—a period at the end of a paragraph. But if it’s not there, I’m just going to break in anyway. And it’s once I start breaking in I do not give up on breaking in.

And, 95 percent of the time—and I think it’s partly because the debaters are uncomfortable and nervous and scared, and they’re on the stage and they’re in front of an audience. Ninety-five percent of the time debaters immediately yield to me, immediately. The other 5 percent of the time they may not hear me or they may say, “I’m almost finished.” And then, if I really think they are, I’ll say, “OK, finish up quickly.” Or if not, I say, “I’m sorry. We need to hear from the other side.”

So, I interrupt just for a bunch of reasons. One of them is so that nobody is talking for more than a minute or a minute and a half.

Another is to keep them on point, is—what the audience—what I think our audience expects to hear, and the reason they learn things, and the reason this is so different from the presidential debates, really, is that the debaters are there building ideas. They’re building one idea on top of another while also trying to dismantle their opponents’ ideas. And so, things need to—you need to stay on point. And so, if somebody starts to wander, which will happen immediately if I don’t do this—not because anybody’s being nefarious, it’s just that their minds wander—I interrupt and I pull them back on point.

Harris: Do you have any examples of a particularly testy debate where—you mentioned earlier like it’s not like Crossfire. But sometimes depending on the topic it might be a very heated, passionate argument that is being made. Can you think of anything in particular?

Donvan: We really discourage personal attacks. And that’s come up a few times. And that’s one where I get kind of all schoolmarm on the thing, and I’ll say—I’ll just scold the debater and say, “You know, we’re really not here for that.”

And it’s an interesting thing because it’s kind of entertaining when there’s a personal attack. That’s why Crossfire exists. But if—again, all of this has been learned from experience. If I let it go on and on it just gets awful, and it ruins the debate, and it gets nasty. And it ruins the atmosphere that we want to create of, hey, let’s all actually learn something through a robust contest here. So, I will call somebody right away. That’s one of the times I interrupt.

If somebody starts attacking somebody’s, oh, I don’t know, financial background or something they’ve done wrong in the past that’s not relevant to the point, our feeling is if we decide that somebody should be put on the stage, then we’re forgiving their past. It’s not relevant anymore.

But we had a very, very rough go back and forth when we were debating whether the U.N. should recognize Palestine. And we had two debaters, two against two.

The side arguing for the recognition of Palestine by the U.N. included Marwan Barghouti, who was with the Palestinian National Council. And he flew over for the debate. But his partner was a guy named David Levy who is a Jew and a Zionist but a very, very strong critic of the way things are going in Israel.

And on the other side we had Aaron David Miller, who has worked for the State Department, and Dore Gold, who was a former ambassador to the U.S. for Israel. And what was really interesting is that the real passion was between the two Jews, not between the Palestinian and the Jews on the other side but between David Levy and Dore Gold, who saw each other as very, very deeply traitorous toward their ideal of what was good for Israel and of the whole concept of Israel.

They both—each saw the other as selling out the higher set of ideals that were behind the founding of Israel. And it got so personal with each of them that a moment came when—they both had the inside seats. The way the debate is set up is I’m in the middle at a little lectern, and right next to me are two tables, one on each side, with the debaters.

And, these two guys had the inside seats on each side. So, they were almost leaning over me with their fingers wagging at each other screaming at each other at the same time. And, I—a couple of times I said, you know, “Gentlemen, gentlemen, let’s hold it off.” And they weren’t even hearing me. They weren’t even aware of me at this point.

And so, I left—the only time I’ve done this. I left my position at the lectern, and I walked around all of these tables, and I went to the—you know, all the way downstage and stood where the—at the edge of the stage near the audience. And I turned around, and I faced these guys, and I raised my arms above my head in that sort of, you know, part the Red Sea gesture. And I just said, “You’ve got to stop. You’ve got to stop.” And I think the theatricality of it, you know, stopped them. They were a little bit surprised that I was doing this.

And so, then I went back to the lectern and I gave, you know, a little bit of a 20-second, you know, “We appreciate that the passions are high, but nobody learned anything really useful over the last minute as you were going through that. And that’s not what we’re about.” And the audience gave a round of applause. The audience is very, very—the audience is so much my ally in keeping these debates on track because they want—I mean, five, 600 people come to these debates in Manhattan where a lot of stuff is going on. They come there because they really love what we’re trying to do, and they want it to happen.

And, you know, even though there was a little bit of titillation to see these guys screaming at each other, you know, a little bit of theatricality, and I’m not against a little bit of that, it was—nothing really was learned during that. And the audience wants to learn. So they all applauded at that point. And they moved on and behaved after that.

Harris: At the end of each debate there’s also a live audience, as you’ve mentioned, and they get to vote at the end. Can you just break down, really briefly, exactly what the voting—how the voting process works? Because sometimes—it seems sometimes sort of counterintuitive the way the voting goes.

Donvan: Well, they have—we equip the hall temporarily with a little keypad that we wire to every seat in the house. And it’s got numbers on it, 1-2-3. And before the debate people vote. And after the debate they vote again. And, the—you push No. 1 if you’re for the motion, No. 2 if you’re against and No. 3 if you’re undecided.

And then we have—it’s all wired into a computer and a spreadsheet, and it tells us, you know, immediately, where the audience stands on the motion. And so, when you say counterintuitive I think what you’re saying is that you may end the evenings having most of the audience on your side but still lose the debate. And that’s because we don’t just go in and vote—it’s because of the two votes. It’s because we say, look, everybody came in here with an opinion already. How do we learn what happened here tonight unless we use that first vote as a baseline and see where things have moved afterwards?

So, in a sense it’s really a measure of who was more persuasive in the evening. So, the team wins who have moved their numbers more than the other side. And since we have a large undecided pool often at the beginning of a lot of votes a team can become—can start out behind and end up behind still but have picked up more of those undecided votes. And that’s why they become the winner, because they persuaded more people to come to their side.

And, it’s not perfect, but it’s the best method that we can come up with.

Harris: What is the outcome that has surprised you the most?

Donvan: A lot of them do, actually. We had a tie recently. It’s the first time that’s ever happened. And we—none of us expected it to the extent that we didn’t have—you know, we have software that puts all of the numbers up onscreen and declares a winner. We didn’t have software for a tie. We had no way to announce it, so I just did it from the lectern.

That debate was—the motion was “Smart technology is making us dumb.” And, it was interesting that it tied on that one. It was also a really good debate.

Harris: Can you let our listeners in on what you might tell the debaters who have lost that you wouldn’t hear, you know, backstage?

Donvan: They hate to lose. They really hate to lose. And it’s kind of awful.

I always go up to them and say—some of them are very sour. And very, very often we’ll hear the losers say, “Well, the other team stacked the audience.” I mean, we hear that a fair amount of times from the losing side. We never hear it from the winning side.

Harris: Really?

Donvan: And, what I say to them, I say to them, “You know, the win-lose thing is, it’s a little bit of an artifact of the situation.”

“It’s a particular audience on a particular night. And we could have the same debate in another place and the result would be different because it’s so audience dependent.”

And then I say, “You know, I don’t mean to sound ‘Kumbayah’ about this to you debaters, but the fact is you picked up—you changed people’s minds tonight.”

“You got people to listen to you who moved from undecided to your side. The other team got more of them than you did, but you did change minds. And that’s all by itself something to be proud of.” And the last thing I say is, “These debates live on and on and on and are presented to other audiences.” I mean, we’re on public radio stations. We’re on—we have a podcast that we—as I said before, it’s distributed free through our app.

And, you know, we have—seriously, millions of listeners at this point. And five to 600 people in New York City happened to vote one way. But what’s going to happen is that debate’s going to be heard by millions of people who are going to hear your arguments. And many of them are only there, number one, because they like debate, or number two, because they started out thinking that they liked what your opponents believe in. But they now have heard your arguments.

And so, I do sort of say—you know, it sounds like little league soccer. But I do sort of say, “You know, everybody wins in this process.”

Harris: Does that—

Donvan: It doesn’t always assuage all feelings, no. No, it doesn’t. It doesn’t. But I’m impressed by anybody who has the guts to get up on stage, especially in light of all of the people who are really impressive people out there who are afraid to who won’t, who don’t want to do the homework, who don’t want to risk losing, who don’t want to face a challenge to their ideas in front of an audience.

That makes me congratulate, really, everybody who gets on our stage, which now at this point has been more than 500 people, I think. And I congratulate all of them. And frankly their ideas are out there now. You know, every day somebody is downloading and listening to them because they were in this unique format. And their ideas are being heard and challenged and tested in a really tough way. And if they stand up to those and persuade somebody, then that means they’ve really succeeded. But it’s hard to tell them that in the moment after they lose.

Harris: Thanks for listening to this episode of Working.

To find out more about John Donvan and Intelligence Squared U.S., and to listen to their archive of podcasts, go to intelligencesquaredus.org. Their fall season starts Sept. 16. Send us your feedback about the show to working@slate.com. And there’s more where this came from. Explore our first two seasons at slate.com/working.

This episode was produced by Matt Collette. Joel Meyer is our managing producer. And our executive producer is Andy Bowers. I’m Aisha Harris. See you next time on Working.

This podcast extra is part of your Slate Plus membership.

Harris: I would like to say very quickly that my friends and I, when we go, we’ve developed a system. You mentioned earlier about how, like, often it starts off mostly undecided when audience guests are there. And we realized that if we all start off undecided, regardless of how we feel about the topic, and then switch over once the debate is over, whichever side we preferred is more likely to sway the votes, just the way that works out.

I don’t know if you were aware of that, but—

Donvan: Well, I would discourage you from doing that because then what’s the point? What’s the point? What do you achieve by doing that?

Harris: Well, I mean, I think it’s like hoping that whichever side you do choose to—

Donvan: Yeah, see, that kind of depresses me because unless you’re saying that you’re also actually sincerely persuadable—but if you are sincerely persuadable, then you could just stand by your side.

But what it then does is it becomes like I’m going to go in and help my side win as opposed to I’m going to go in and really keep an open mind. And even if you succeed in that, I’m not sure what you’ve achieved. All you’ve done is succeeded in skewing the reality. And maybe, you know, a press release goes out that this side won and that side lost.

But I don’t think you’ve achieved much more than that. And so, I assume—you know, I mean, we assume that some people game it but probably not in significant enough numbers to sort of blow up the integrity of the whole thing. But I’ve often—this is a good opportunity for me because I’ve often wanted to say this. What have you really—what have you achieved by doing that if you really just want to go in and have your side win?

It also suggests that you don’t have full confidence in your side’s ability to win.

Harris: Well, I think on our end it’s a matter of—a lot of times we actually don’t know. Like, we’re undecided.

Donvan: And that’s totally fair.

Harris: But, like, the added bonus of once you are persuaded by whichever side is that, you know, that side has a better chance of being the victor.

Donvan: That’s true. You definitely have more power regardless of what game you’re playing if you move from undecided, absolutely.

Harris: Right. Yeah.

Donvan: So, you’re holding it in reserve.

I mean, the honest truth is that everybody is always asking me which side I thought won. And I’m usually not very good on picking which side won. I think I’m wrong more than half the time. But, on most issues I ask myself at the opening which side would I be on at the opening. And I would be undecided every time, not because I’ve—not because I have—I want to, like, hold in reserve the chance to push the side that I favor, but because I say to myself I may hear something tonight that I’ve never considered before. And I may be persuadable.

Harris: Yeah.

Donvan: So, it’s more for that reason that I think I would be undecided at the start of almost everything. There are very, very few issues where I go in thinking there’s no way my mind can be changed. We did the death penalty debate, and I had a number of friends go who said I just—you know, I’m willing to listen, but there’s no way my mind will be changed on this issue, on both sides of that issue. And that’s one where I actually would go in once again undecided. I wanted to hear what they had to say.