The “A Certain Justice” Transcript

Why does Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas so often stand alone? Read what Dahlia Lithwick talked about on her latest episode of Amicus.

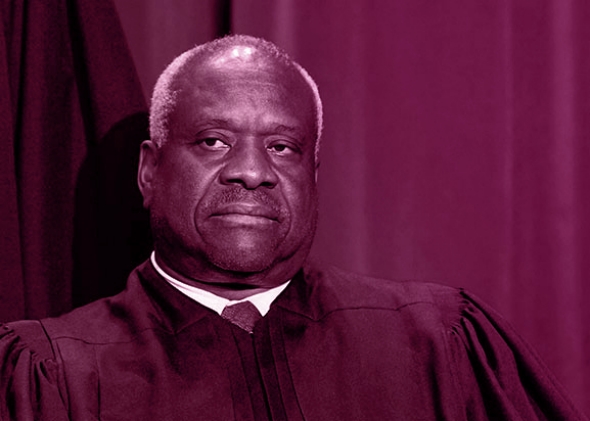

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images.

We’re posting transcripts of Amicus, our legal affairs podcast, exclusively for Slate Plus members. What follows is the transcript for Episode 20, in which Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick chats with Carrie Severino about Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ silence in court and the role he’s played on the Roberts court. Severino is chief counsel and policy director for the Judicial Crisis Network and a former clerk to Thomas. Lithwick also chats with historian Douglas Smith about the bedrock principle of “one person, one vote.” To learn more about Amicus, click here.

We’re a little delayed in posting this episode’s transcript—apologies. This is a lightly edited transcript and may differ slightly from the edited podcast.

Dahlia Lithwick: Hello, and welcome to Amicus, Slate’s podcast about the Supreme Court. I’m Dahlia Lithwick, Slate’s Supreme Court correspondent. And with just three weeks left until the end of the court term and twenty decisions still outstanding, the U.S. Supreme Court this week handed down, well, one decision.

This prompted longtime Supreme Court watcher Linda Greenhouse to quip in the New York Times that, “At that pace, it would be Thanksgiving before the dourt issued its decisions in the same-sex marriage cases.” Despite the trickle of decisions, there’s been a lot of action at the court as the justices hash out their docket for next term. So later in the show, we’re going to look at one of the big, big cases they’ve agreed to take up, a case challenging the bedrock principle of “one person, one vote.”

But first let’s talk a little bit more about this term. And specifically, one member of the court who we don’t talk about much on this show. And that’s because anybody listening in on oral arguments, as we like to do on this show, hardly ever hears from him at all. I’m talking, of course, of Justice Clarence Thomas, who, despite his silence in the courtroom, has had an awful lot to say on paper these past few weeks. In dissents. In dissents from denials of certiorari. And in all sorts of other ways that we don’t often pay attention to.

We wanted to better understand what is going on with Justice Thomas this term. And so, we decided to invite a former clerk of his, Carrie Severino, to join us. Carrie is chief counsel at the Judicial Crisis Network, a conservative advocacy group in Washington, D.C. Carrie, welcome to Amicus.

Carrie Severino: Thanks so much for having me, Dahlia.

Lithwick: So, we wanted to start—I know you and I don’t agree on much. But I think we might agree on this one thing. It seems like a good idea to start with it. And that is: You know, one of the things that drives me batty is people who think they’re court watchers, who say, “Oh, Clarence Thomas. You know, they should have just given Scalia two votes. You know, his clerks do all the work for him. You know, he doesn’t deserve to be there, and has never done anything.” Am I right that this is kind of a knock that has been going on for a long time, and it’s profoundly unfair to Justice Thomas, who in my view has a fully realized, completely independent, and coherent constitutional architecture in place?

Severino: Oh, absolutely. Possibly the most independent architecture of anyone on the court.

It’s something that we’ve seen for a long time. Whether that’s, you know, subtly racist in nature, whether it’s just because they’re frustrated that he is one of the most conservative members of the court, I’m not sure. But ever since he was on the court, people were saying, “Oh, he’s just voting that way because Scalia did.” And actually, now that some of the notes have come out, from other justices releasing their papers, we’ve found that there are cases that—the press is all talking about him following Scalia. It turned out Scalia followed him on some of these early cases.

So it’s a challenge when you’re a Supreme Court Justice. Because they don’t talk to the press. All of the internal workings are secret. And so no one can stand up and say, “Oh, no, no, no. That’s not how it happened.” And the clerks are all sworn to secrecy. So it’s hard for people to realize how independent he is. But it certainly comes out if you look at his opinions. He is very consistent in his opinions. But he’s also not afraid to disagree when he thinks that the other justices are not taking the correct line.

Lithwick: So let’s talk about this independence.

Because I think it’s in full flower right now, we’ve seen in the past two weeks. Correct me if I get this wrong. But Thomas dissenting in the Abercrombie & Fitch EEOC case alone. Dissenting in Elonis, the Facebook free speech case, 7-2. A major dissent from denial of cert in the San Francisco guns case. Another dissent this week in Zivotofsky. That’s the passports case.

So am I right that he is really, really doing something different this term, where he is standing absolutely alone and kind of bracketing himself, even from the court’s conservative wing?

Severino: Well, he certainly is standing alone. But actually, that in and of itself is not very different. He or Justice Scalia kind of go back and forth for who is the least likely to agree with their other colleagues. And Justice Thomas at least as often as Justice Scalia, probably the most often of any justice, has a unique perspective. And part of it is because he has a very solid sense of his own principles.

Once he has decided a case, he doesn’t go back and say, “Oh, you know, water under the bridge. We’re going to go another way.” It made work clerking for him very nice. Because it was—especially since he’s been in the Court for over two decades now. If there is an issue that he has really thought through and he has a position on it, he’s going to stay consistent.

Lithwick: And is there something different going on this term in another realm, that’s maybe a little bit more subtle? Which is just seeing him and Justice Scalia kind of taking whacks at one another.

So I’m thinking again of this Zivotofsky case, this passport case, that sort of has to do, in the larger sense, with who decides foreign policy, the executive branch or the Congress. But in a deeper way, I think, really smokes out this different reading of the text and purpose of the constitution, the text and meaning. Massive disagreement between Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas. And including Justice Scalia, I think throwing an elbow and sort of accusing Thomas of thinking like, you know, George III.

Is that new? Or is that just something that’s been going on forever as well?

Severino: I really think that’s a—they’re consistently the most aligned with each other of those two. And honestly, these sort of detailed arguments about what version of their originalist conception of the law is the correct one? They certainly go on. They definitely have differences. But there is so much more in common between Justice Thomas and Justice Scalia than, say, Justice Thomas and Justice Ginsburg or Justice Sotomayor.

So while the differences are there and are clear, they aren’t getting in the way certainly of their friendship or their working ability together. And it’s the kind of thing that, you know, probably gets pretty far in the weeds. The broad questions, they certainly are on the same page, in terms of how their jurisprudence runs. Although there’s going to be distinctions, because they both have their own point of view.

Lithwick: So, now I want to turn to—because I think you’re right. I think that when I look at the SCOTUSblog statistics of, you know, justices agreeing with each other, it’s clear this term so far Justices Scalia and Thomas—

It looks like they’ve agreed 76 percent of the time. That’s pretty high. But then we see that it really drops off between Clarence Thomas and Chief Justice John Roberts. That looks to be like, about a 65 percent agreement rate. So I think that, you know, for people like me, who for a long time said, “Oh, you know, there’s a block of four conservative justices, and they play from the same playbook,” that 65 percent looks like that’s not a lot of agreement, in their agreement. Is that representative of something going on? Is that Clarence Thomas drifting to the right? Is that the chief drifting to the center? Or have they always agreed less than I thought they did?

Severino: You know, I think, Justice Thomas, as a general rule, is pretty good to set your compass by. He doesn’t move. And sometimes he has changed his mind on things. But he tells you when he’s doing it. He’ll write separately and say, “You know what? I ruled this way. And now I’ve realized that was incorrect. I’m going to go a different way.”

I think what we’re seeing is, I think some people are very concerned the chief justice has gone wobbly. He has really, in the last few terms in particular—although, it probably characterizes his term on the court in general—hasn’t been the kind of consistent, conservative jurisprudence that you see from a Thomas or a Scalia or an Alito. So I think that’s more the chief moving toward the center. And sometimes in this term, it seems like he’s vying for Justice Kennedy to be the swing vote on the court.

So he’s certainly not a consistent conservative.

Lithwick: And is that, you know, the chief—and we’ve talked about it so much on this podcast. He’s very institutionally anxious, right? I mean, his concern is legitimacy of the court, the appearance of unanimity. You know, not politicizing the court in an election year. Those sort of laundry list of maybe chief-specific concerns. And is that legitimate in your view? I mean, are those things that John Roberts should be worrying about? Or is it getting in the way of him doing his job?

Severino: Well, we actually don’t know, of course, what is really going on in John Roberts’ head. All of this is sort of speculation. I think the challenge is a lot of it is a speculation coming in ways and in timing where it looks like there are a lot of people using these alleged concerns about the institution to try to lobby the chief justice to vote in certain ways. Because you always see it coming from a particular angle. You don’t hear people saying to Justice Ginsburg, “You know, it looks unseemly that you have such a high consistency of voting with Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan. Why don’t you flip every once and a while just to shake things up?” And I think that’s because, ultimately, switching one’s vote in order to try to placate people on the outside who have their own political interests in the case, isn’t actually the role of a judge. That’s the role of a politician. And it’s one of the aspects of politicians we normally don’t like. The fact that they’re willing to switch their principles or appear to be willing to switch their principles, based on sticking their finger in the wind.

And that’s not what we want a judge and a justice to do. We want someone who’s going to be, as the chief who put it himself, “calling balls and strikes.” Not saying, “Hey, you know what? I keep on calling strikes on the home team. We’re going to do a few on the away team, just to make things look even and fair.” So I hope those aren’t his reasoning behind these cases. Unfortunately there are cases that give people that impression. The biggest one, of course, being NFIB v. Sebelius, the major Obamacare decision that he historically appears to have flipped at the last minute.

People felt that that was something the chief did not because of the broader legal principles, that he just felt compelled by the law but because he was trying to grasp at anything straw he could not to overturn the law. And unfortunately the way that the chief voted in that case has suggested to people that maybe he’s gettable. Maybe we can influence him on these grounds. And I think that’s unfortunately disappointing and undermines the view of the court as independent of politics.

Lithwick: Carrie, can you just clarify? Because I think what you’re saying is that Roberts is really uniquely solicitous of, sort of, criticism from the left. And that he’s somehow less prone to listen to criticism from the right. And yet I guess I would say there was an awful lot of people, after the 2012 Obamacare case, on the right who were so furious with him. That at least if you’re sort of going to get engaged in that, “Who’s bullying Roberts?” it’s certainly arguable that he’s now been as terrorized by critics from the right, as he has been by critics from the left.

In other words, if he’s wobbly, I’m not sure which way he wobbles, in light of the blowback that he got after 2012. Is that fair?

Severino: You know, I think there may be people on both sides, as I said, that view him as gettable, at this point. And so you’re seeing people writing op-eds, hoping that Chief Justice Roberts will read them. And I think that is a problem. As a mother of a toddler, I can identify. It’s like, once you give in to the tantrum, now you’re just inviting more tantrums.

And that is how I view what happened there. If it looks like you’re giving in to the tantrum. Everyone going, “Oh my gosh, the world’s going to in.” The court is going to sink in people’s view, or at least in the media’s view, or my view. Then suddenly people say, “Oh, hey. It worked. We’re going to try it again.” And so I’m hoping he maybe will have learned this, having had toddlers of his own, and will say, “You know what? On second thought, we need to just stick with the program.” You don’t see people writing those op-eds toward Justice Thomas. Because they kind of know it’s not going to do any good. And you know, maybe if we saw an indication, however the justices can manage that.

That, “You know what? We’re going to shut off the TV. We’re not going to be reading the paper to find out what’s happening about ourselves. We just need to do our job and let the chips fall where they may.”

Lithwick: I guess my heart goes out to the chief, if I were to use your toddler analogy. I feel like, in addition to squawking toddlers, which is the country, he has this mother-in-law, right? Which is, you know, John Marshall and his hero, William Rehnquist, and the chiefs before him, who really did put the institution above their personal views sometimes.

And I think he really, right or wrong, I think he feels bound by a kind of chief justice-y ethos that gets in the way of always doing what he wants. It sounds to me like, in your view, that doesn’t hold a lot of water.

Severino: Well, I think to suggest that voting contrary to what you actually believe the correct legal answer is isn’t doing any favors for the court as an institution. If the court looks like an institution that has political influences and not legal ones, we’re all poorer for that.

And I don’t think that’s what Americans want, be they liberal or conservative. I think we’d all rather have a court that we think is really trying to take politics out. Just make the decisions based on the law itself.

Lithwick: Carrie, I want to take you back to Justice Clarence Thomas for a minute, just because I’m obsessed with him this week. And I want to play to you a little bit of audio from Feb. 22, 2006. You probably know this date by heart, although it’s before you clerked. This is Holmes v. South Carolina.

And it’s the last time he asked a question at oral argument.

Counsel: I see my time is about up.

Clarence Thomas: Counsel, before you change subjects. Isn’t it more accurate that the trial court actually found that the evidence met the Gregory standard?

Counsel: No, he specifically found, I believe, from my reading, that it didn’t meet the Gregory standard.

Thomas: Well, he says, “At first blush, the above arguably rises to the Gregory standard. However, the engine that drives a train in this Gregory analysis is a confession by Jimmy McCall White.”

And then, he goes on to say that that …

Lithwick: So Carrie. I guess my question is the one anybody who talks about Thomas gets all the time. Which is, why did he stop talking? He hasn’t asked a question since then. Much to the chagrin of, I think, a lot of folks. But he has a lot of pretty principled arguments for why he does not ask questions at oral argument. I wonder if you would take a moment to help unpack that for us.

Severino: Sure. When you talk to the justice about it, he’ll explain what the court was like when he first came on the court.

In 199, they took tons more cases than they do now. Instead of like 70, 80 cases a year, they were taking 120 cases. He got started a little bit behind everyone. So he’s rushing to catch up. They had not just cases being heard in the morning but in the mornings and the afternoons. So there’s almost twice as much work going on. And no one would ask a question. The justices wanted to hear what the advocates had to say. They realized that the advocate, as much as the justices, read on the cases by then.

The advocates actually know more than them. And want to find out what is it that they feel is the most important thing. Particularly, sometimes on these detailed, factual questions that you—you know, the Justices can study the law, but they might not know the facts of the case in detail. So, the culture that he started on the court was very different. It’s not like it is now, where it’s almost a three-ring circus. The justices are interrupting each other. You don’t get a full sentence out at the beginning half the time before someone jumps in with a question. They’re sort of rhetorical questions. They’re trying to score points.

They’re often trying to score points against each other, not even—you know the poor, hapless advocate there is kind of just being used as fodder for them to make their arguments against each other. And I think he would say it’s worse for the way it is now. It’s not necessarily teaching us anything new about the case. So I think until he finds that they quiet down a little bit, he sounds like he doesn’t want to add to the noise.

Lithwick: And my I also take your temperature on this hypothesis, Carrie? And that is, I think that when Justice Clarence Thomas takes heat for not having spoken in nine years, he cares not at all.

Am I correct in saying that the more people criticize him, the more he just says, “I don’t need to speak this year, either.”

Severino: You know, I’m not even sure of the extent to which he knows the heat that he’s taking. Because he just doesn’t pay attention to that stuff. He doesn’t read what the papers are saying about him. If there’s something he needs to see that’s particularly interesting or that he might like, his wife will show it to him.

But he doesn’t really care what the media thinks. Again, he thinks, you know, “I took this oath. I’m going to do this job the best I know how. And if these people want to complain? You know, that’s fine for them. I’m the one who has to sit in this seat.” I don’t think he’s going to play games to try to please the media, at all. He’s going to do what he thinks is right. And good luck trying to change him.

Lithwick: So my last question, Carrie, is that we’ve given all of our guests, in the last couple of weeks, free range to just wildly predict what’s coming up in the coming couple of weeks.

And you can certainly exercise your right to say, “I am not making a prediction, because we’ll see what we’ll see.” But certainly, if you want to tell how you think things are going to go down in the Burwell case, and the Obamacare 2.0 case, or in the marriage-equality cases, we will love to hear it. And we will not hold you to it.

Severino: Please don’t bet on this. Because Justice Thomas always used to make us guess before he told us how the votes came out when we were clerking. He made us guess what the votes were.

And we’d read all of the information. We had talked to other clerks. We had all sorts of inside information, and we still got it wrong, regularly. And so, that was just to keep us humble. I really think that the biggest cases—which in my mind are King v. Burwell and Obergefell, the marriage cases—are really too close to call. If I had to give the thumb to one, I felt, after oral arguments, a little more confident that King v. Burwell would go with the text of the statute and that there would be a redefinition of marriage in the marriage cases.

But I could see them both going the opposite direction, you know, depending how the wind is blowing that day.

Lithwick: Listener at home, do not bet based on this advice. Carrie Severino is chief counsel and policy director of the Judicial Crisis Network. She was also a former clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas in the 2007–2008 term. Carrie, thank you very, very much. It was really a joy to have you on Amicus today.

Severino: Thanks. Great to be here.

Lithwick: Now, before we move on to our next guess, we’re going to pause for a few words about today’s sponsor, the Great Courses …

Now, I love deeply exploring complicated legal issues. And I’m guessing you do, too, if you’re listening to this podcast. So, that’s the motivation behind the Great Courses. It includes over 500 courses in all sorts of subjects—from law, to history, yoga, science, math—available in audio and video formats. Now, one cool thing about the Great Courses is it’s taught by really smart and engaging professors, in ways that are accessible to you

And the Great Courses series called “The First Amendment and You: What Everyone Should Know” is a really good fit for Amicus listeners who want to dig deeper into the First Amendment. It explores, in depth, how the First Amendment, at just 45 words, is kind of still the pillar of our democratic system. The Great Courses’ “The First Amendment and You” explores everything from commercial speech, hate speech, and the religion clauses in a deep and engaging way. Now, the Great Courses created a special, limited-time offer for Amicus listeners.

If you order from eight of their best-selling courses, including “The First Amendment and You,” you’ll get them at up to 80 percent off their original price. So go to thegreatcourses.com/amicus. That’s thegreatcourses.com/amicus, and learn a little bit about the First Amendment and you. And while we’re on the subject of lifelong learning, we wanted to make sure you knew about another exciting podcast project happening right here at Slate. It’s called Slate Academy, and it’s available exclusively to Slate Plus members.

Our very first Slate Academy is currently underway. It’s a nine-part history of slavery, hosted by our very own Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion and featuring loads of leading scholars of slavery. Visit slate.com/academy to learn more.

Last week the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear a big, fat Texas case for next term that will challenge the fundamental principle of “one person, one vote”, possibly replacing it with one voter, one vote. Joining us now is Doug Smith.

He’s a historian and author. And his most recent book is On Democracy’s Doorstep: The Inside Story of How the Supreme Court Brought “One Person, One Vote” to the United States. Welcome to Amicus, Doug Smith.

Doug Smith: Thank you very much.

Lithwick: So Doug, this kind of gets lost in the jargon. So can you just unpack what the words one person, one vote signify? What is the kind of legal, constitutional question? What was it attempting to redress?

Smith: So the concept of “one person, one vote” emerges in the 1960s, in connection with a series of Supreme Court cases. And the basic issue of these cases was, how were state legislative districts to be drawn? Were they to be drawn based on a straight population basis? Or should they be drawn based on other factors, such as geography? So at its most basic level, the concept of “one person, one vote” was that in all elections, every person’s vote is weighted exactly the same.

So that in portioning and redistricting, essentially every district would have the same number of people in them.

Lithwick: And now, Doug, could you just briefly summarize the nature of the Texas challenge that the court agreed to hear last week?

Smith: Sure. So my understanding is that the appellants, who are primarily residents of rural areas, have argued that their vote has been diluted by the fact that even though the districts in Texas have the same number of people in them, that they don’t have the same number of voters.

And that in the rural areas, that there’s higher numbers of actual voters, or even eligible voters, than in many of the urban areas, which include a lot of people who are counted for the purposes of reapportionment who are not in fact eligible to vote. And so their argument is that state senate seats, in this case, ought to be apportioned based on the number of eligible voters, not on the number of all people who normally would be counted in a census.

Lithwick: And let’s try to be super clear about who it is that may be counted as a person, but not as a voter. And that tends to be people under the age of 18.

Smith: Sure. Documented citizens who are—I’m sorry. Documented residents who are not citizens of the United States. So recent immigrants who are here legally and are counted in the census but are not eligible to vote.

And then, of course, in some states there are, in some cases, very large numbers of individuals who have lost the right to vote because they’ve convicted of felonies. So felony disenfranchisement plays a role in this as well.

Lithwick: So is it fair to say that that’s a demographic—those folks who are counted as people who live in an area, but are not voters in an area—that tends to skew Democrat?

Smith: To my knowledge—and this is—when we start to look at it in those terms, we’re beginning to move a little bit out of my area of expertise. But certainly, the evidence would be that they tend to be more urban residents who, when they are able to vote, do tend, at this point in time, to skew towards Democrats.

Lithwick: Now, Doug, I think the notion of “one person, one vote” seems like such a deeply entrenched principle that probably a lot of listeners think it’s in the Constitution. Right? That it’s just like that, you know, it’s in the Federalist Papers. That it’s just established from the get-go, “one person, one vote” means what it says. But as you point out in your books, prior to the 1960s, representation in this country was just kind of an entrenched system of minority rule.

And residents of small towns enjoyed huge disparate political power, right?

Smith: Absolutely. And it’s funny. The first of that is, when I, over the past ten years, when I’ve been telling people or friends what I was working on and I talking about the Supreme Court’s “one person, one vote” decisions in the 1960s, typically I would get a sort of puzzled look. As if, “What do you mean? Hasn’t it always been that way?” And as you point out, no. It’s been, for the most part, anything but.

So you know, prior to the 1960s, you had a whole hodgepodge of systems. It was, you know, very much state by state. There are many state constitutions that did base representation on population. And many of those same states also required, you know, reapportionment every 10 years. But often that just didn’t happen. Throughout the 20th century, as the population of the United States became increasingly urban … state legislatures just refused to reapportion.

And so as the populations became increasingly urban, resident of rural areas and small towns began to wield vastly disproportionate political power. And it wasn’t just in—when I first started this project, I thought—I came at this as a historian in the American South. And I thought that I was really writing a regional history. And I quickly discovered what a national story this was. So that you had, I mean, every region of the country, there was, you know, a fair amount of malapportionment.

And often for very different reasons. You know, California, where I now live, it began as a state where it required equitable apportionment in both branches of its legislature. But as Los Angeles and Southern California got bigger and bigger, folks in San Francisco and in areas outside of Southern California were worried about their loss of political power. So they, to cite just one example, you know, in the 1920s, changed the system so that on the California state senate, no senator could represent more than three counties. And no county could have more than one state senator. So you ended up with a situation by 1960 where Los Angeles has 6 million people and has one state senator. And there’s three rural counties, up on the eastern side of the Sierra Mountains, where 14,000 people have the same amount of electoral power. So you see. I mean, vastly disproportionate. And that was true in many states throughout the country.

Lithwick: But wasn’t there also this strand of argument that said rural voters were better Americans and more truly representative of what American voters should be?

Smith: There were many folks who did often talk about rural residents as better Americans. And for reasons that, in some ways, actually echo much of what we hear today. Late-19th, early-20th century massive waves of immigration in the United States. In the urban areas. New York, you know, Philadelphia, Boston, et cetera, et cetera, were swollen with immigrants. And so, part of, I think, the reaction then was not entirely unlike what you hear now.

And although I’m sure the appellants in the Texas case would deny this, that it has anything to do with current immigration debates, it’s hard to see it not being separated from that.

Lithwick: Now, correct me if I’m wrong, Doug. But it was not a foregone conclusion, in the early 1960s, that the court is going to wade in to the malapportionment problem. What is it that decides to drag the court into this conflict, which is, at least initially, looks like it’s kind of happening in the states, and underground, and the court could certainly steer clear of it?

Smith: Correct. And it was a real surprise, to many, when the court did decide to step in. And I think the sort of the brief back story is that the—malapportionment—it was clear every 10 years, with every census, that it was getting worse and worse. And so it was becoming more and more of an issue. In terms of the politics of malapportionment, it’s really post–World War II, when you have groups of, especially the League of Women Voters, at the state and local level, are really driving this.

You know, and these are women in municipal areas, you know, from Nashville, Tennessee, to Memphis, to Seattle, to Minneapolis, who are concerned about all sorts of things. And they recognize the extent to which malapportionment is preventing the legislature from providing the necessary funding for things like education, welfare services, and a whole host of issues that need addressing in increasingly urban communities. And so it’s very much of a grass-roots, local, and then state issue, in terms of it being addressed.

The state legislatures consistently just refused to get involved. I mean, it’s asking state legislators essentially to vote themselves out of office. So they don’t do anything. State courts frequently recognized that there is a violation of state constitutions, but say that the state legislatures alone can fix this. And then the federal courts, for the most part, sort of stayed out of the issue of malapportionment throughout the ’40s, the ’50s, and into the early 1960s. And so it was no foregone conclusion by any means.

It was not a given when the Supreme Court decided in November 1960 to hear arguments in Baker v. Carr, a case that had come out of Tennessee.

Lithwick: So Doug, maybe walk us through what the holding was in Baker v. Carr. And then we can talk through the other reapportionment cases that come after.

Smith: Sure. So in retrospect, and sort of over the years, people often refer to Baker v. Carr as the case that established the principle of “one person, one vote”.

But Baker, in fact, did not do that. In Baker, the court, very purposely, did not reach any decision on the issue of what standards of apportionment the equal protection clause would require. But what Baker did do was it said that malapportionment could in fact be a violation of the equal protection clause. And that therefore, the federal courts could hear cases alleging malapportionment. And so this was really big first step, which essentially opened the doors of the federal courts to lawyers and plaintiffs to challenge state legislative and congressional malapportionment.

And over the course of the next two years, dozens and dozens of cases were filed alleging state legislative and congressional malapportionment. And then, that’s what sort of set the stage for what comes two years later.

Lithwick: Now, Doug, what comes two years later, of course, will become Reynolds v. Sims. This is the attorney general of Alabama in the opening moments of oral argument, 1963, Reynolds v. Sims.

Richmond Flowers: There’s four propositions I want to make to the court. One. Legislative reapportionment should be resolved without federal interference. The court should reconsult Baker v. Carr, or clarify Baker v. Carr, and return to the original Constitution proposition that courts do not interfere with the political structure of state.

Two. The court should limit themselves, under the time-honored constitutional provisions for checks and balances, to the function of judicial review of legislative acts. They should not invade the providence of the legislature.

Lithwick: Doug, can you tell us, in very nutshell form, what the ultimate holding of Reynolds v. Sims was and what it signified going forward?

Smith: Reynolds, in a nutshell, said that both chambers of a state legislature must be based on population equality and struck down any notion of being able to have what was often referred to as a little federal system. You know, where one branch is based on population, one branch is based on other factors. And so, it really held that all legislative bodies in the United States had to be based on population.

Lithwick: Doug, help me understand one final, technical point. Which is, Reynolds v. Sims ruled that voting districts have to contain close to the same number of people. But they didn’t answer this question that’s now before the court. Of, you know, whether it’s persons or voters. Why didn’t the Warren Court just answer that question?

Smith: Right. And that’s a great question. And it seems like a head-scratcher. And you know, I actually,I had one conversation, in the course of my research, with one of Earl Warren’s law clerks about that issue. And as far as I can recall, the response was sort of along the lines, “Well, we did look into it.” That at that particular time it did not seem like you would have, that the result would be fundamentally different, whether you counted people or counted voters. And I think it’s important to recognize that 1964 was the year before the immigration policies in the United States changed dramatically. And so, you’re at the end of a 40-year period of very narrow immigration. And so in terms of large numbers of noncitizen residents, there just simply weren’t as many at the time. So in that sort of narrow sense, it may not have been as much of an issue.

Part of the assumption, back to your original question, is that virtually everywhere, people meant people. And it was persons who were counted. And the court at the time was more concerned in places like Tennessee. Whether you use people or voters, that they were actually counted fairly. And so even though Tennessee used voters, they weren’t counting them fairly. And so that was more the issue than whether it was people versus voters.

Lithwick: Doug, my last question for you is that you seem to have some insight into the very origin of the term one person, one vote, that could shed light on this new, upcoming cert grant. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Smith: Sure. And I should say, parenthetically, before answering that directly. I spent a long time trying to trace the origin of this. And the phrase one man, one vote is actually what was used most commonly at the time. And trying to trace the origins of that is a little problematic. Although, there’s a lot of evidence that it’s used often in Africa, actually. The African National Congress was using one man, one vote. But in the United States, even the League of Women Voters referred to one man, one vote.

But it was the all-male Supreme Court that actually used the term one person, one vote, when everyone else was using the phrase one man, one vote. The phrase one person, one vote actually appears for the first time, from what I’ve been able tell, in a Supreme Court opinion. Not in Baker, and then not in Reynolds. But a case in between. A case that was decided in 1963, which dealt with the constitutionality of Georgia’s country unit system. Georgia had this system that where in all of their statewide elections—say governor, for instance—you didn’t just simply add up the number of people that candidate A or candidate B.

But you looked at it on a county-by-county basis. And each county was assigned a certain number of units. And so I think it was, I don’t know, the eight largest—I may be off by a little bit. But the eight largest counties got six unit votes. And then, the next 20 largest counties got four unit votes. And every other county got two unit votes. Well, Georgia had something like 150 or 160 counties, 120 of them being very small rural counties, which only had two unit votes each.

But that was more than enough to offset any population issues with Atlanta or the other big cities. So literally it allowed for minority rule to flourish in Georgia. And so in striking that down and saying that the Georgia county unit system was unconstitutional, William O. Douglas wrote the opinion. And this is one of those moments, as a researcher, where you get very excited, because they found his original draft. And he amended his first draft to write, “The conception of political equality—from the Declaration of Independence, to Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, to the Fifteenth, Seventeenth, and Nineteenth Amendments—can mean only one thing. One person, one vote.”

And to your original question, what I found most relevant here is that someone—I have always assumed a law clerk, based on a variety of factors—tried to change one person, one vote to one voter, one vote. And Douglas refused. And so, it was very clear—in his mind and presumably in the mind of the majority at the time—that the issue was one person, one vote, not one voter, one vote. And so that I find highly relevant to the claim today in the Texas case.

Lithwick: Doug Smith is a historian.

He’s the author of On Democracy’s Doorstep: The Inside Story of How the Supreme Court Brought “One Person, One Vote” to the United States. Doug, thank you so very much for joining us today on Amicus.

Smith: Thank you. It was my pleasure.

Lithwick: We have second sponsor on today’s show. And it’s FreshBooks. And I’d like to tell you a little bit about it. If you’re someone who runs your own service-based business, spending less time on pesky administrative tasks means having more time to focus on your clients’ work. Which is why you should give FreshBooks a try.

FreshBooks is the invoicing solution that makes it incredibly simple to create and send invoices, track your time, and manage expenses. Even if you’re not a numbers person, you’ll be shocked at how easy FreshBooks is to use. For your free 30-day trial, go to freshbooks.com/amicus, and enter AMICUS in the “How did you hear about us?” section of the sign-up page.

As you may or may not know by now, Amicus is but one of many fantastic podcasts in the Panoply network. And before we leave you today, we wanted to give you a taste of another one of them.

Jeffery Rosen: I’m Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, and host of the We The People constitutional podcasts. Every week I call up the top liberal and conservative constitutional scholars in America to debate the constitutional issue of the week. And this week I’m joined by Erwin Chemerinsky, from the University of California Irvine School of Law, and Richard Epstein, from the New York University School of Law. We discuss this week’s landmark events at the Supreme Court, including a fascinating ruling about the separation of powers in foreign affairs.

The question is, who decides whether or not to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel? Is it the president or Congress? We also preview an upcoming decision in a case about housing discrimination and the government’s power to address it that could have large implications for the future of race discrimination in America. All this and more on our We The People constitutional podcasts.

Find us on iTunes, and learn more at constitutioncenter.org.

Lithwick: And that’s going to do it for this episode of Amicus. As always, we’d love to hear what you think. Our email is amicus@slate.com. If you want to catch up on older Amicus episodes, you can always find them all at slate.com/amicus. We’re told some folks have been binge-listening to all of the prior episodes as they prepare for their bar exams.

Good luck. And if you want to help others find out about the show, one great way to do just that is by leaving a short review on our iTunes page. Just search “Amicus” in the iTunes store; click the ratings and reviews tab. We really appreciate that support. Thank you to the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, where our show is taped. Our producer is Tony Field. Our managing producer is Joel Meyer. Andy Bowers is our executive producer. This week’s excerpts from the Supreme Court public sessions were provided by Oyez, a free law project at the Chicago Kent College of Law, part of the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Amicus is part of the Panoply network. Check our entire roster of podcasts at itunes.com/panoply. I am Dahlia Lithwick. We’ll be back with you next week for another edition of Amicus.