You Will Not Comment on This Article

A primer on commenting on Slate.

Photo illustration by Tashatuvango/Thinkstock

This article is free to all Slate readers to promote our membership program, Slate Plus. Try Slate Plus free for two weeks! Go to slate.com/plus to learn more.

This article is also part of a package of coverage about commenting on Slate. Slate Plus members can also check out “Are Comments Sections Worth It?,” a debate featuring writers Amanda Hess, Rachael Larimore, Amanda Marcotte, and Will Oremus. And then head over to “How Should Slate Improve Its Comments Section?,” a members-only open thread discussion.

You will probably not comment on this article.

At least that’s what my analysis of recent Slate commenting data suggests. In September, for example, 99 percent of all Slate readers did not comment on any Slate article they read. Most readers just aren’t commenters. No need to bury our lede.

As a result, most conversations below Slate articles are small. Slate has published more than 12,000 pieces since the beginning of 2014. Only 12 percent of those pieces attracted participation from more than 100 individual commenters. In comparison, the average Slate article attracts many thousands of readers—or at least clickers.

Yes, often the comment icon at the top of an article displays a number greater than 100. But that’s a measure of comments, not unique commenters; the icon’s count may double, triple, or infinity count those commenters who have much to say. That’s true of one of Slate’s most-commented pieces of 2014, “The Rise of the Ironic Man-Hater” by Amanda Hess; it garnered about 4,900 comments from only 343 commenters, meaning the average commenter left about 14 comments below the article.

Slate articles almost never engage more than 1 percent of their readers as commenters. It’s a small crowd, but that doesn’t seem unusual. Across many types of websites, it’s often observed that there are many more people consuming content than creating it. Some people have referred to this a 1 percent rule of Internet participation.

So the odds are against you. You will probably not comment on this piece.

But maybe you were just reading the Drudge Report?

That could change the odds. Because one predictor of how Slate readers will behave on the site is where those visitors arrive from.

Slate tracks where its readers come from and some of what they do once they're here. Like how long they spend reading an article, or whether they leave any comments. And there are certain sites whose readers, when they come to Slate, appear more likely to leave comments.

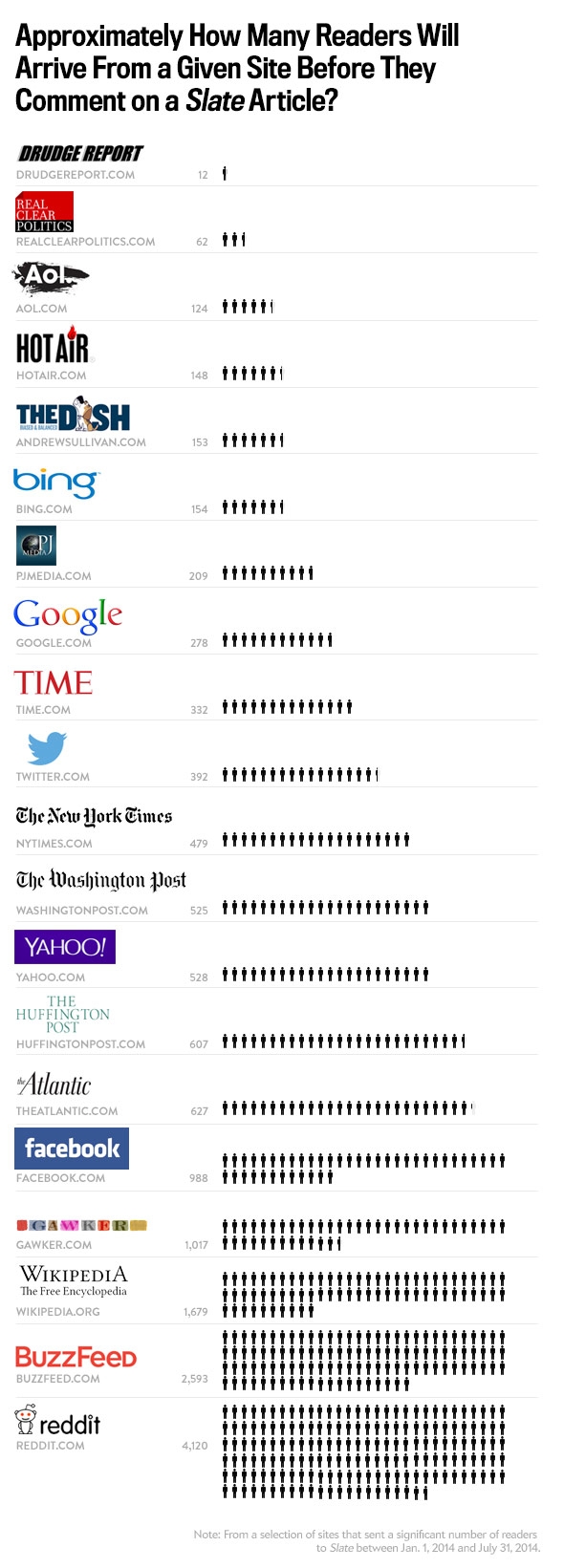

For example, on average, for every 12 readers who arrive at Slate from the Drudge Report, one comment is left below an article. By comparison, it takes 4,120 visitors from Reddit to generate a single comment on Slate.

Here’s a selection of websites that send a significant number of readers to Slate. We measured the volume of commenting activity that occurs relative to the number of readers each site sends to Slate.

What explains the garrulity of Drudge visitors? One motive for commenting is to register disagreement; it’s possible that Drudge readers simply disagree with Slate more often than an average visitor. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center suggested that Drudge and Slate cater to ideologically opposite audiences. Most conservatives indicated that they trusted Drudge and distrusted Slate while most liberals distrusted Drudge and trusted Slate.

Perhaps this difference of opinion predisposes the Drudge reader visiting Slate toward more commenting. In affirmation of that hypothesis, Drudge is not the only site atop the chart above that caters to a right-of-center audience. Readers arriving from Hot Air and RealClearPolitics, for example, also leave a lot of comments at Slate.

But apart from their politics, the sites listed above are also different in kind. At the top of the list are some aggregation-focused sites like Drudge. Some news outlets cluster in the middle. Social media sites rank in the bottom half. Several of the sites near the bottom of the list, including Gawker, Wikipedia, and Reddit, are known for hosting their own, active commenting communities.

There’s some causation versus correlation mess here that’s work for another day. The point is, what kind of site a reader arrives from may predict whether they will become a commenter.

You are more likely to comment on this article if it’s about feminism or race.

And also parenting or religion. You have a lot to say about these topics.

In 2014, from Jan. 1 through Sept. 24, there were 209 Slate articles that attracted more than 300 unique commenters. When Slate publishes an article, it assigns certain topic tags for archival purposes. We looked at which topic tags were assigned most frequently to this sample of 209 articles. (We took a few analytical liberties: We grouped some similar topic tags together; we assigned topic tags to articles that had none in a few obvious cases; and we held aside Dear Prudence columns, about which more below.)

Approximately 40 percent of these most-commented articles dealt with issues of feminism or race. Not very far behind were a significant number of articles about parenting or religion. Excluding Dear Prudence columns, about 70 percent of Slate’s most discussed articles dealt with one of these four themes (sometimes more than one).

You can see how that’s reflected in some of Slate’s most discussed articles of the year (thus far). In the table below, you’ll see three different ways of measuring which articles ranked as Slate’s “most discussed.”

In the above table, the third tab ranks 10 articles that received the most comments. The second tab ranks the articles that engaged the greatest number of unique commenters; since there’s some relationship between traffic and commenting, this second tab may be biased toward more popular pieces. We’ve made some effort to control for traffic in the ranking displayed on the first tab. It ranks the articles that engaged the greatest share of theirs readers as commenters. None of the three rankings are perfectly scientific measures, but they usefully survey some of the themes that might motivate readers to become commenters.

Incidentally, adding should to a headline also seems to draw out commenters.

You are more likely to comment on this article if it’s a Dear Prudence column.

Which it’s not. But we can’t understand commenting on Slate without mentioning the Dear Prudence commenting community. More than 40 percent of the 209 articles looked at in the above analysis were Dear Prudence columns. Dear Prudence columns are the most reliably talkative place on the entire site, and this is because many of the commenters are loyal, longtime commenters who return every week.

Maybe you would comment more if Slate improved the quality of its moderation efforts?

“Right now, we're totally half-assing moderation,” said staff writer Amanda Hess in our Slate Plus debate about commenting on Slate.

Hess might be on to something. In a report entitled “Online Comment Moderation: Emerging Best Practices,” the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers surveyed 104 news outlets from 63 countries. They found that news outlets “delete or block an average of 11 percent of comments left on their sites, because the content is offensive, irrelevant or spam.” Slate appears to fall considerably beneath this average. From July through October, the months for which tracking was available, Slate moderated about 4 percent of all the comments it received.

Of course, perhaps Slate commenters are simply more decorous than commenters on other news sites? At odds with that interpretation are reports from Hess and other Slate writers. “I envy writers who feel that their comment sections give any insight whatsoever into how people are genuinely reacting to your arguments. But when it comes to writing that touches on class, race, or gender issues, a cesspool is a near certainty, unless you have rigorous moderation,” said DoubleX contributor Amanda Marcotte in the same Slate Plus debate about commenting on Slate.

It takes a lot of moderation to keep the troll population at bay.

If it’s true that Slate could stand to moderate more intensively, perhaps Slate should consider enabling comments on fewer articles. Currently, Slate enables commenting on almost all of its articles. This spreads the magazine’s moderation resources over many articles, most of which will attract only a handful of commenters. If Slate enabled commenting on fewer articles, it might allow more moderation resources to be concentrated on improving the discussions that attract the greatest number of commenters.

The New York Times, for example, has approximated this less is more approach to commenting on its site. In 2013, Bassey Etim, a community manager for the Times, answered a question on Quora about the paper’s moderation strategy. Before they open commenting on an article, Etim explained, they consider the news value of the story, project reader interest, review whether they’ve recently had comments on the topic, and estimate whether or not they have sufficient moderation resources available to handle the projected commenting volume. “The costs to this approach are obvious—it takes a long time, and many stories do not get comments. But NYT readers expect the highest-quality everything from us, so that’s what we deliver,” said Etim.

By improving its understanding of which stories you are most likely to comment on, perhaps Slate could focus its limited moderation resources where they’re most needed. Fewer, better threads—quality over quantity, in other words.

All that said, you will not comment on this article. You just won’t.

Because I disabled commenting on this article. Ha! An elaborate ruse. But for a good cause! Here’s what we want you to do instead: tell us, really—“How Should Slate Improve Its Comments Sections?” Go join other members and Slate staffers in that members-only open thread. And make sure to also check out our Slate Plus debate, “Are Comments Sections Worth It?”