Tween Spirit

Revisiting an adolescence spent hunting for Nirvana rarities on CD bootlegs in dusty record stores.

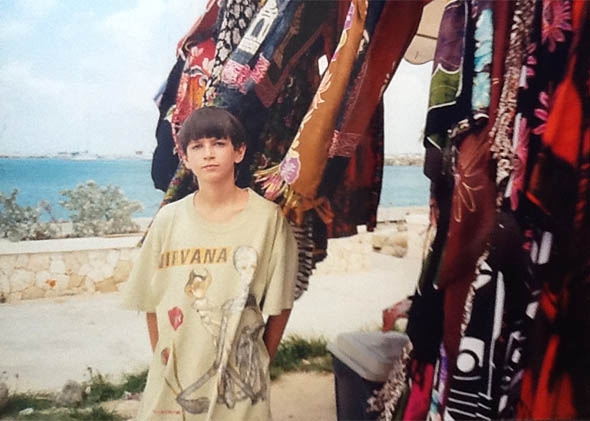

Courtesy of Ljuba Lyass

This content is free to all Slate readers to promote our membership program, Slate Plus. To learn more, go to slate.com/plus.

I had called ahead, as usual, so I knew what they had. Someone had brought in a used copy of the “Lithium” single, which came with a B-side I had never heard before called “Curmudgeon.” When Chris, the owner of the CD store where I did most of my shopping, told me that he had “Lithium” available for just $6, I’d hung up the phone and hustled out the door.

I was in fifth grade, and listening to Nirvana was the only thing I liked to do. All I thought about was Nirvana. I wore a different Nirvana T-shirt to school almost every day. Above my bed, I had a black-and-white poster of Kurt Cobain’s face with a banner at the bottom that said, “I hate myself and I want to die.” To this day I can’t believe my mom let me have that in my room.

Needless to say, I owned all five of the band’s official full-length albums. But I absorbed them quickly, and after a while, the songs had made such deep grooves in my brain that I had basically stopped being able to hear them. I needed more.

The time I spent as a 12- and 13-year-old fulfilling this need has been on my mind this week because of the new Kurt Cobain documentary, Montage of Heck. The film is extraordinary, both in terms of the archival footage it contains—recordings of a teenage Kurt reading out loud from what sounds like a diary, for instance—and the formally inventive ways in which it brings that footage to life on the screen. Watching the movie as a 30-year-old many years after selling off or losing track of the Nirvana collection I amassed over the course of my youthful obsession, brought back visceral memories. What a thrill it had been for young me to hear rare, unreleased songs like “Here She Comes Now” and “Opinion”—both of which appear in the documentary—for the first time.

The concept of “rarities” initially came to me by way of a compilation CD called “No Alternative,” which included songs from iconic ’90s acts like the Breeders and Soundgarden. I didn’t really care about those bands, but I bought the CD anyway because I’d heard a rumor that it contained a secret Nirvana song—one that didn’t appear on any other release and wasn’t even listed in the compilation’s liner notes. Sure enough, after skipping through the whole CD on my boombox, one track at a time, I heard Kurt’s voice ring out over a series of warm guitar chords, singing a tense but buoyant melody that I had never heard before: “And if you save yourself/ you will/ make him happy/ he’ll give you breathing holes/ and you’ll /think you’re happy.” I didn’t know what the song was called or where it came from. I just knew it was amazing—easily as good as anything on Nevermind—and that hearing it made me feel like I was bearing witness to something precious. (For the record, the song was “Sappy,” though for a long time fans mistakenly believed it was called “Verse Chorus Verse.”)

Soon I learned there were untold Nirvana songs out in the world that most people, including me, would never hear unless they sought them out. Some of them were B-sides to official singles like “Lithium.” But many more were only available on bootlegs—unauthorized CDs released by entrepreneurial fans who had somehow gained access to previously unreleased material. Bootlegs were illegal, and as a result, were only available in certain independent record stores. In many cases they were labeled and sold as “imports,” a half-hearted effort, I guess, to make them seem more legitimate.

In my hometown there were just a few stores that sold bootlegs, and because they were rare, they were usually priced between $20 and $30. For a guy whose income came from mowing his mom’s lawn and baby-sitting for the neighbors, these were pretty steep sums. But the knowledge that these CDs were out there, and that they contained Nirvana songs that I would otherwise never get to listen to, not only gave me something to save up for, but also gave me a purpose in life. I became dedicated, addicted even, to the work of getting my hands on each and every song. Bedroom demos, outtakes, live performances, rehearsals, alternate versions of stuff I was intimately familiar with—I wanted them all. And because this was in the early 1990s, before a collector could simply search for anything he wanted on eBay, my main way of finding them involved calling stores and asking them what they had.

As I learned by browsing through shelves and reading fan websites on the Internet connection at my dad’s office, there were dozens if not hundreds of Nirvana bootlegs in the world. I remember buying one called Twilight of the Gods because I liked the photo of Kurt on the cover and because it included an outtake I’d never seen anywhere else called “Return of the Rat.” I bought Europe 1991 because it had a live version of “Oh, the Guilt,” a song that appeared on a rare split 7-inch with the Jesus Lizard (which I also bought). Shelling out $30 for MCMXCIV was a no-brainer because it was supposed to be Nirvana’s last show ever. With time, my stack grew taller, as the lawn was mowed with increasing frequency.

I quickly discovered, though, that only some bootlegs were worth the money and effort it took to acquire them. One in particular, called Outcesticide, was known to be the very best one on the market, and the company that made it, Blue Moon Records, had a reputation for presenting fans with very choice, exclusive material. There was actually a series of four Outcesticides—Vol. I was called In Memory of Kurt Cobain, Vol. II was The Needle & the Damage Done, and so on—and I was desperate to get my hands on each one.

It was not a straightforward process. Because Outcesticide—the name was a pun, sort of, on the official 1992 Nirvana B-side collection Incesticide—was such an in-demand title, Blue Moon’s competitors in the shady world of Nirvana bootlegs tried to ride their coattails by making imitations. As a result, there were several fake Outcesticides in circulation, and you had to be careful to avoid getting a subpar “clone” or an imposter. To this day, the “bootography” published by the fan website Live Nirvana features a comprehensive Outcesticide FAQ.

I can still remember when I came across my first Outcesticide in the wild. It was the fourth and, at that point, final volume in the series—subtitled Rape of the Vaults—and I found it at a store I didn’t usually go to because it was far from my house and required getting my mom or dad to drive me. As I held the CD in my hands and scanned the track list, I was seized with intense desire for the treasures it contained. An alternate version of “Pennyroyal Tea,” possibly my favorite Nirvana song, which had only been released on an impossible-to-find CD single and on the Walmart version of In Utero. An early recording of “Spank Thru,” which I had read somewhere was the first Nirvana song ever. Something called “Clean Up Before She Comes,” recorded on a four-track in 1988. “D-7,” a cover of a song by one of Kurt’s favorite bands. A demo of “Drain You” with alternate lyrics.

It took me two weeks to save up enough money to buy it. I worried the entire time that someone else would snatch the CD before I had the chance, and I would call the store every day to make sure it was still there. When I finally brought it home, I felt as though I had successfully pulled a very large and beautiful fish into my boat. And while those alternate lyrics to “Drain You” weren’t terribly exciting—as far as I could tell the only difference was Kurt says “I travel through a tube and end up in my infection,” instead of “your infection”— Outcesticide IV did contain a truly bewildering rendition of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” in which Kurt sang in a deep, faux-plaintive voice that made him sound like a cartoon version of Morrissey. (It turned out this was a recording of Nirvana’s 1991 appearance on Top of the Pops, the British TV show, where the band was required to play along to a recording of their big hit single. Kurt protested by singing in a silly voice.)

I don’t know what I did with my copy of Outcesticide IV, in the end. Maybe I sold it on eBay? Or maybe it’s still in a closet somewhere in the house where I grew up. Some irrational part of me wishes I still owned it, even though, as I write this, I’m listening to a version that’s been uploaded to YouTube, along with every other once-hard-to-find piece of Nirvana history under the sun. The fact that this is possible is amazing to me, but I’m glad I discovered this world before it was so easily experienced: As much as I’m enjoying these songs, hunting for them and watching my collection grow was, for me, a pretty crucial component of the lifestyle. I recently discovered that there is now an Outcesticide V—Blue Moon put it out in 1998, after I had moved on from my Nirvana obsession, to ska and other things—and though it’s sitting right here, and though it includes a demo version of the Hole song “Live Through This” with Kurt singing backups, I’m sad to say I have no desire to put it on.

That’s not to say that 30-year-old me regrets anything. In fact, if you couldn’t tell, I’m quite proud of the dedication I showed in loving Nirvana, even if the phase only lasted a couple of years. When it was announced last year that the new documentary would be called Montage of Heck, I felt a thrilling jolt of insider status from recognizing it as a reference to a sound collage that Kurt made in his room, and which appeared as the penultimate track on Outcesticide IV.

When I finally got to see the documentary last week—a friend here at Slate gave me a screener DVD that I stuffed in my shoulder bag with a familiar hunger—I stared with wide eyes at the amazing material the filmmakers had dug up. This wasn’t some clip job—director and producer Brett Morgen had gotten access to 200 hours of previously unreleased music and audio, and he picked out some stunning artifacts. Hearing these was a humbling experience—like being taken on a tour of an ancient castle that I thought I had already explored as thoroughly as possible. Now that the castle was open to the public, it was clear that I had only seen a tiny fraction of it. And while that did make me feel mildly annoyed—why hadn’t the guys from Blue Moon Records found this stuff back when I was in a state of mind to care about it even more than I do now?—I was mostly just blown away by the footage and stunned by how close it made me feel to an artist I never knew, but will always love.

Without a doubt, the most transporting recording featured in Montage of Heck is Kurt’s 90-second acoustic solo cover of the Beatles song “And I Love Her.” Listening to this song, hearing Kurt’s deep, sad voice transform it from a merely pretty melody into something hauntingly tender, pretty much turned me into a 13-year-old again. The overwhelming feeling: I can’t believe this exists. What else are rarities for?