The “How Does Samuel R. Delany Work?” Transcript

Read what Slate’s Working podcast asked the acclaimed science-fiction novelist about his career.

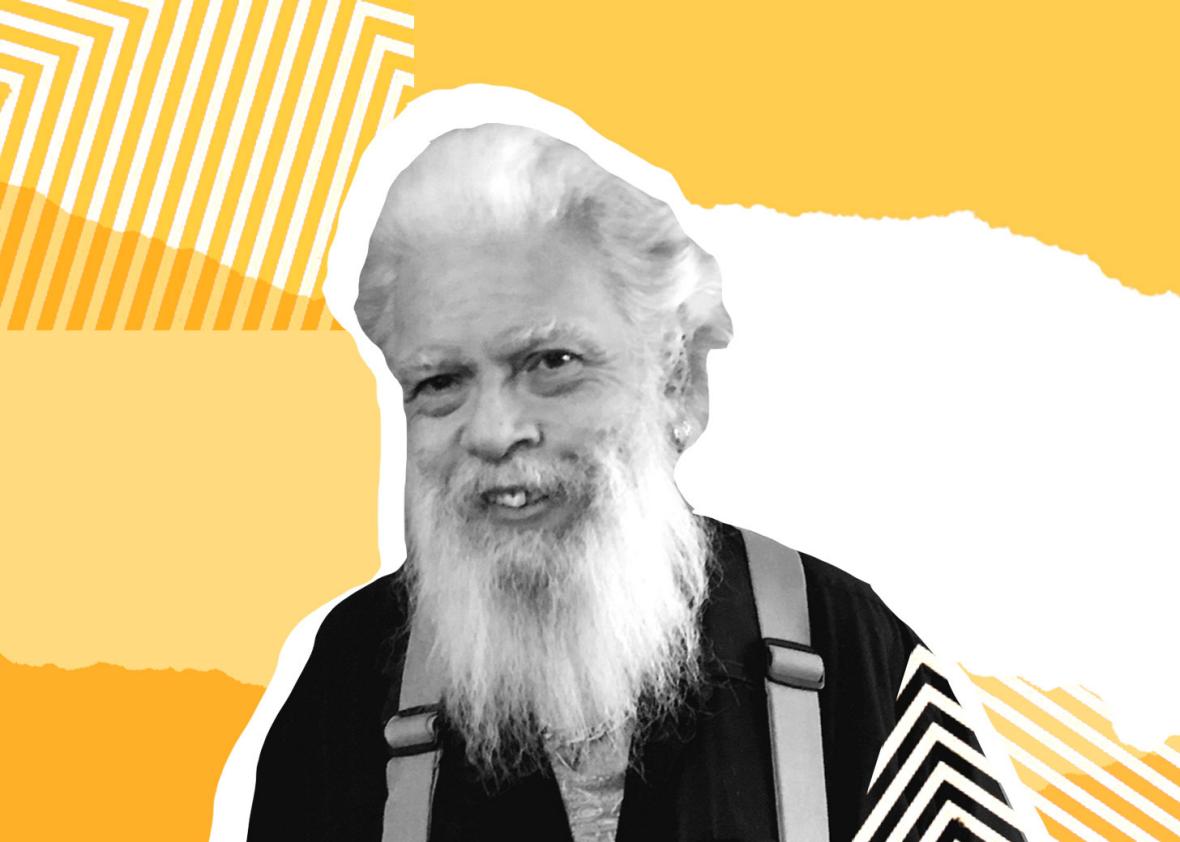

Photo illustration by Slate. Photo by Erin McGregor.

This is a transcript of the Dec. 17 edition of Working. These transcripts are lightly edited and may contain errors. For the definitive record, consult the podcast.

Jacob Brogan: This season on Working, we’re talking to individuals whose jobs touch on aspects of LGBTQ life. As regular listeners of the show probably know, I did a Ph.D. in English literature before I became a journalist and started hosting the show, among other things. And one of the people I wrote about in my dissertation was this remarkable queer science-fiction novelist named Samuel R. Delany. Delany’s books, Dhalgren, Nova, Trouble on Triton, The Jewels of Aptor, and so many others are among the most remarkable explorations of desire and its limits in any genre. I couldn’t be more excited about this episode in which we sat down to chat with Samuel R. Delany, who goes by the name Chip to his friends, about his writing process, about the way that his own particular desires have shaped his work, and even about the role that dyslexia plays in his writing, reading, and revising process. This is one of the episodes I’m happiest that I’ve gotten to do and I’m so, so happy that I get to share it with you.

What is your name and what do you do?

Samuel Delany: My name is Samuel Delany. All my friends call me Chip. And I am a writer.

Brogan: What kind of writer are you?

Delany: Well, most of what I write is science fiction. A lot of what I write is criticism and nonfiction and I’ve written some other things, other kinds of fiction than science fiction. I write generally all over. And I do a lot of Facebook posts.

Brogan: A lot of Facebook posts? So you’ve been writing science fiction since you were 19. You wrote your first book, Jewels of Aptor, at 19. You published that when you were 20. You are 75 now?

Delany: 75, very close to 76.

Brogan: Very close to 76. You’ve also written, as you suggest, memoirs, criticism.

Delany: Comic books.

Brogan: Comic books. You wrote two issues of Wonder Woman.

Delany: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Brogan: You’ve written sword-and-sorcery fantasy.

Delany: Yes.

Brogan: Your Nevèrÿon Quartet.

Delany: Nevèrÿon.

Brogan: Nevèrÿon?

Delany: Nevèrÿon.

Brogan: I should have known that from the diacriticals.

Delany: There you go. That’s why I put them in.

Brogan: Nevèrÿon. That’s the pleasure of radio. You get to hear the correct pronunciation. You’ve even written pornography that you, I think, identify as pornography?

Delany: Yes.

Brogan: Given all this, given the range of your work, is there a reason that you maybe primarily identify in some cases as a science-fiction writer?

Delany: Yeah. Science fiction is probably where I have the largest reputation and I think a lot of people think of me as a science fiction. I was elected the Damon Knight Grand Master of Science Fiction two or three years ago.

Brogan: The 30th Grand Master of Science Fiction.

Delany: Yeah, 30th or 31st, I don’t remember.

Brogan: So it’s just what you’ve been doing.

Delany: Yeah. And as I said, I was also a professor. I’ve been a professor at several universities. First in 1975 at SUNY Buffalo. Then I was mostly supporting myself by writing. And then I went to University of Massachusetts at Amherst for 11 years and then for two years up at Buffalo again. Since then at Temple University down here in Philadelphia.

Brogan: But you’re no longer teaching today?

Delany: Yeah, no. The teaching is more or less over with.

Brogan: Are you still writing today?

Delany: Yeah. I have to write and I have to travel around and do talks. You make more money talking about science fiction than you do writing it. In fact, I think you make more money talking about writing in general than you do writing.

Brogan: But you have published literally dozens of books over the course of your 55-odd-year career.

Delany: Right, but not dozens of science fiction.

Brogan: Not dozens of science-fiction books but your most recent full-length book, Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders.

Delany: Yes, that’s a great big long one. It’s that one with the black spine.

Brogan: Eight-hundred-some pages.

Delany: Four, but who’s counting?

Brogan: Four?

Delany: Eight-hundred-and-four pages.

Brogan: Eight-hundred-and-four pages, OK.

Delany: But who’s counting?

Brogan: So that book came out in 2012. Are you still writing novels now or is most of your writing ... I mean, I know you mentioned that you publish on Facebook. A lot of that is essayistic or memoiristic.

Delany: Short, very short.

Brogan: Short writing.

Delany: Short writing, yeah.

Brogan: Are you also still writing novels?

Delany: Novels, no. I have the two novels that were not published that I’ve put together and I’m curious whether I may be able to place them. I have a collection of letters coming out with my university press. They hopefully will get around to publishing. And another collection of essays that, again, I’m waiting for them to move forward with.

Brogan: So this is a show about working, about the way we work. I wonder, are you the kind of hyper-disciplined writer who writes 1,000 words every morning between 7 and 10 a.m., or do you have a more chaotic schedule?

Delany: It’s chaotic. I try to do the writing pretty much first thing in the morning after I get some coffee and oatmeal. That’s the first.

Brogan: Coffee and oatmeal is your—

Delany: I get up. I go to the bathroom. I come out and I make some oatmeal and what have you. And sometimes I get to work even before the oatmeal is done if I’ve got something that’s really in my head. And those things tend to be nonfiction of that sort. Facebook, those are the Facebook posts.

Brogan: Yeah. What about in periods of your life when you are writing fiction, science fiction or pornography or fantasy or whatever genre you’re working in, is your schedule different there than it is these days?

Delany: It’s changed every time I’ve moved to a new neighborhood. I’ve only been here for a few months now.

Brogan: In your apartment in Philadelphia?

Delany: Yeah, here, yeah. Up until a couple of months ago I was at 1123 Spruce St., which was another neighborhood, a different kind of neighborhood. The neighborhood was in Center City. It was on Spruce Street and it was much more lively. I would go and get a latte every morning from the café on the corner, the Green Street Café, and I would usually try to take a picture of the first person I saw pass by on the street and post that. That would be part of my Facebook things. There are nowhere near as many people on the street in this neighborhood. This just is a much less populous place.

Brogan: So you have your coffee here in the apartment then, instead?

Delany: Yeah, mm-hmm (affirmative).

Brogan: Then do you work out of this apartment or do you have a separate office that you—

Delany: No, no. We are now in my office/living room.

Brogan: Can you describe this space that you work in to us?

Delany: Well, there’s a wall of books behind there. Then there’s another wall of books. And then there are some boxes over there that are left over from the move, which is stuff that I still haven’t got unpacked. This is my assistant over here.

Brogan: Hello.

Bill: Hi.

Delany: Bill.

Brogan: Hi, Bill.

Delany: He’s the one who knows what buttons to push.

Brogan: On the computer?

Delany: Yeah, mm-hmm (affirmative).

Brogan: Do you work at the computer yourself?

Delany: Yeah. I can do some of my things. I can do my writing and what have you. I’m very dyslexic and have been all my life with the result that even the writing goes fairly slow, goes relatively slow. I always have to go over and correct things again. Even the Facebook posts have to get rewritten and rewritten because I cannot type the word dear without writing D-E-A-E-R. There’s always an extra E that comes in and then I have to take it out. The dyslexia has been described ... It’s not a problem with your memory. It’s pathological absentmindedness, which I think is a very good description of it because you can’t shake it. Some of it is habitual absentmindedness like the D-E-A-E-R.

Brogan: I wonder, though, if that pathological absentmindedness has shaped your own writing practice, the obligation to go back over to review.

Delany: It made me very much aware of style because everything had to be retyped and rewritten and at first when I was young, it was a matter of typing it three times. Then when you get to word processors, there is no ... Just the whole notion of the discrete draft vanishes and you just rework and rework things forever.

Brogan: Do you—

Delany: It’s not a new draft until somebody else has read it first. Then you’ve written another draft.

Brogan: So you’re, I assume, a pretty aggressive reviser, then?

Delany: Yes, I am. Yeah. In fact, I basically, I revise. I don’t write. I revise.

Brogan: Yeah. You’re known in your science fiction and in your other writing as a high stylist in many ways and often an experimental one. Even in your more mainstream-ish science fiction there are still stylistic and technical flourishes in terms of the way you organize chapters. But also even more granularly at this syntactical level. How much of that kind of stylistic play that shows up in so much of your work comes through in those first drafts, and how much of it is a product of revision and rewriting?

Delany: I couldn’t tell you. Most of it. It varies per page. Sometimes I have to rewrite a paragraph five, 10, 12 times. Sometimes one will come out more or less correct the first time except for the oddness spelling. If someone catches it, then it’s fairly easy to correct. Bill sits there and looks over my shoulder and points to the extra letter or where I’ve done something stupid. My emails have to be rewritten again and again and again. I used to say I can’t sign my name to a check without rewriting it three times because I’m likely to misspell my own name. And I do, I actually do misspell my own name when I’m writing checks and things like that.

Brogan: You’re also, I assume from looking around this room but also from knowing your work, a pretty copious reader.

Delany: I was, I was. I find it’s harder and harder for me to read as I get older. It really is. That’s another thing that’s definitely changed with getting older. I don’t feel that much like I’ve aged. I feel if I sit back and just ... I feel like I felt like when I was 12 years old. But I do know my voice sounds a little different. My voice sounds a little rougher to me than it sounded when I was 12.

Brogan: It sounds very similar to me.

Delany: Well, OK. But I can hear all the little ...

Brogan: Sure.

Delany: … the little things that are different about it. I did a lot of singing. I used to be in singing groups and things like that.

Brogan: You were in a folk group as well at one point.

Delany: Right, yes. And we actually were planning to record. I wrote a book about it.

Brogan: Heavenly Breakfast.

Delany: Heavenly Breakfast, yeah. And I’m in touch with one of the members of the Heavenly Breakfast group who came to see me not too long ago, which was great, a guy named Brett Lee, which was really nice. I went over with him and put him back on the train and what have you. Good guy. Very, very, very sweet young man, although now he’s 60-something now. I think of him as a sweet young man because the time I saw him before that he was about 18 or 19. He’s now just hit 60s.

Brogan: So not to return too aggressively to the question of style and composition, but does that musical background, has it ever informed the way you write?

Delany: Yeah.

Brogan: Do you think of a kind of musicality in your own prose?

Delany: Right, yes. I’m interested in what the sentence sounds like, it’s rhythms and how they play with one another. I don’t put too many ... Watch out for those adverbs. If they’re not doing something really important, get rid of them. I’ve written a book on writing. It’s right behind you. It’s called About Writing. It’s directly behind your head.

Brogan: I see it.

Delany: Can you see it?

Brogan: I saw it earlier. There it is.

Delany: There you go. Yeah. There’s a whole group of 10 things. The noun can stand up to one adjective, two at the most. Or you have to be doing something really special to use more and things of that sort.

Brogan: So thinking about the spareness of style.

Delany: Yeah.

Brogan: As well as the experimental, I won’t say “excess” but ...

Delany: Right.

Brogan: Extremism, perhaps, that you can sometimes reach. One thing that, again, looking around this room, looking at the many books in here—

Delany: This is about a quarter of my whole library. I lost a few about a year ago.

Brogan: Oh, no. I’m sorry.

Delany: One of the reasons I wanted the moving is because I had to give up and get rid of three quarters of my library. This is literally a fragment of what it once was.

Brogan: And even to the extent that it is just a fragment of it, one thing that I really notice in this room, looking at the books that surround you as you write today, is their own variety, diversity, and so on. Here you have your own books mixed in with the comics of Linda Barry, the theory of Giorgio Agamben, the novels of Don DeLillo. Is that—

Delany: Roger Zelazny, Theodore Sturgeon.

Brogan: A lot of classic science fiction as well.

Delany: Not a lot, a little classic science fiction.

Brogan: A little classic science fiction. The Comics of Persuader.

Delany: The poems of Robert Duncan.

Brogan: Yeah. There’s this tremendous variety in here. For you, as a writer, has it been important to literally and figuratively surround yourself with that kind of thematic, stylistic, generic diversity?

Delany: Right, yeah, sure. You know, I used to read the Barry Wintersmith’s comics when they were coming out.

Brogan: Conan artist.

Delany: Yeah. Who was really an extraordinary artist. I liked that stuff very much.

Brogan: Yeah. I mean, given all these forces that you’re dealing with, all these ideas that are coming at you, all these ideas that are channeling through your work, I wonder are you an outliner or do you just dive into a story or an essay and write it as it comes?

Delany: I do some outlining and I do lots of rewriting, as I said, the outlining is part of the rewriting. I will outline something. I’ll start writing it. I have an ideal form, which doesn’t cover everything. You start writing and when you’re about halfway or a third of the way through, you see how close you’re following the outline and then whether you want to re-outline it and see if it’s changed your way. That’s how I got through the Nevèrÿon series, which ended up being 11 novels and short novels and a few short stories. Where the basic form of the science-fictional/sword-and-sorcery-story series is the problem, you write a piece and the solution of piece A becomes the problem of piece B, which is not the progression of novel chapters. So it’s a very different form from the chapters in a novel.

Brogan: The stories, the novels that compose that collection ... I’m going to say the name of it wrong.

Delany: Nevèrÿon.

Brogan: Nevèrÿon.

Delany: Accent on the second.

Brogan: Nevèrÿon.

Delany: Nevèrÿon, on the second syllable.

Brogan: So the novels and stories that composed this, what you call “quartet” sometimes, because it’s contained four books.

Delany: Returns of Nevèrÿon is the title of the whole series. The series is 11 stories and novellas and novelettes, which were simply divided more or less arbitrarily into four volumes. They could fit into four volumes. The second volume is a complete novel.

Brogan: Those stories, though, are themselves stylistically quite diverse. You talk about the solution of story A becoming the problem that motivates ...

Delany: Story B.

Brogan: Story B and so on. There are characters that run through them, Gorgik the Liberator, his former slave.

Delany: Gorgik.

Brogan: Gorgik, I’m sorry.

Delany: Hard G.

Brogan: Learning a lot about mispronouncing things that I’ve been reading for a decade today and loving it. Gorgik the Liberator, who is this former slave-turned-revolutionary figure over the course of the series but also these other figures, an actor, who is a sort of Socrates stand-in.

Delany: Yeah. And it is no accident and one of the things you learn is that in this language, Gorgik, the term “gorgie” is a slang term for the male penis.

Brogan: It’s also, as you’re suggesting, ribald, sexual.

Delany: Yeah.

Brogan: And among other things, this series contains what is generally recognized to be the first American novel about AIDS, The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals, which is a remarkable story, book, novel, some of which takes place in our own New York in 1984, some of which takes place in this fantasy kingdom.

Delany: Fantasy world, yes.

Brogan: Nevèrÿon, am I saying that one right?

Delany: Well ...

Brogan: Nevèrÿon, as it’s undergoing a plague of its own.

Delany: Nevèrÿon, if you read it, it’s “Never yon” and if you put the accents on it, it’s “Nev air eon.”

Brogan: Across never.

Delany: Yeah.

Brogan: But I guess what I’m getting at, the kind of problems that you are opening up in these stories are not the kind of problems that a casual, maybe we would even say careless, reader of fantasy might associate with the genre. You’re grappling in these books with, in some cases, pressing and immediate issues of the moment in which you wrote them.

Delany: Yeah, oh yeah. Sure, yes. AIDS was going on. Margret Heckler made her announcement of the “discovery” of the AIDS virus while I was writing the book. There’s an account of my sitting there watching it on television in the book.

Brogan: Yeah. Over the decades your work has grown increasingly explicit about preoccupations with sex and sexuality, especially around questions of the sort of experience of sexual minority, of queerness, homosexuality. You’ve sometimes suggested that science fiction, maybe even fantasy—not maybe even fantasy. Maybe fantasy as well, genre generally may be especially amenable to these kinds of themes, these questions of sexual and also probably racial minority because it is, itself, a marginal genre.

Delany: Now put a great big negative sign in front of what you’ve just said and you’ll make it correct.

Brogan: All right. Tell me the correct thing.

Delany: The correct thing is that there is nothing special about science fiction that makes it amenable to doing that. There’s nothing special about it. It is simply a genre. So much of the science fiction that actually gets published is published by proto-fascists and historically has-beens.

Brogan: That’s right.

Delany: Often they’ve been interesting fascists and some of them have been somewhat more benign than some others but basically it’s people like Heinlein and Jerry Pournelle and what have you, like that were really far right.

Brogan: This is a debate, as I learned recently, that dates back at least to the first World Science Fiction Convention.

Delany: Convention, yeah. Sure, yeah. A lot of the people on the East Coast were very much on the left and when I say on the left, I mean they were socialists and they were the young ... They grew out of things like the Young People’s Socialist Alliance and things like that. The people on the right coast were people who were very much on the right. For many years the most popular, the Heinlein’s and what have you, Heinlein and even Bradbury was a West Coast writer, and basically nice guys. I talked with Heinlein once on the telephone when he was trying to solve—he was a big deal—he was trying to solve a political problem and he was using the fact that he was the biggest deal around to bring people together and he made a suggestion and I think everybody ... I don’t even remember what he was dealing with, but I know that it made sense after the phone call so I went along with it. People like Isaac Asimov, again, was very much a lefty.

Brogan: Yeah. He actually had a quite copious FBI file because of that.

Delany: Yeah, right. Exactly.

Brogan: Let me ask that question a different way. You are black and gay. Your work deals explicitly and maybe increasingly so over the years with themes of race and questions of sexuality.

Delany: Yes, mm-hmm (affirmative).

Brogan: Have you found science fiction to be a useful lens for thinking about those issues to the extent that you think about them in your work, or is it just an accident of the genre, the para-literary form, to use a term that you’ve embraced in the past, that you’ve chosen to embrace?

Delany: I think it does. I mean, Theodore Sturgeon was a married gay man. I was married for a while. I have a child. Possibly Ted thought of himself as bisexual. I don’t know. I never got a chance to ask him. I know that there are bisexuals out there. I have met people who just are, really are bisexual. I am not one, which is why I live with Dennis today. So that’s the way that works. I write about those things because those are the things that fill up my life. That’s why I’m interested in them. That’s why I write about them. I write about them as fiction too, although I do use a fair amount of observation as well.

Brogan: Yeah. Given the long-standing push and pull between left and right in science-fiction fandom and among science-fiction writers, have you received resistance from fans of your work as these themes grew more explicit in your prose and your fiction, your other writing over the decades?

Delany: Depends on what you mean by fans.

Brogan: Good point.

Delany: Huh?

Brogan: I said “good point.”

Delany: Which is to say I have received hate mail. I can still remember when the third volume of the Return to Nevèrÿon was published, Flight from Nevèrÿon, I remember getting a letter from some kid in Canada. I assume it was a kid because of the handwriting. And I opened it up and there was this, written, and it began, “Fuck you. You think you’re so smart” and so forth and so on. It just went on from there about how awful he thought this stuff was and it was because the stuff was about gay material and obviously he had not picked up a sword-and-sorcery book planning to read about gay people.

Brogan: A lot of those books, whether or not this young man realized it, were very gay all along.

Delany: They were, yes. I know. And certainly the Robert E. Howard, on which was the basis of the sword-and-sorcery stuff, although the—

Brogan: The original Conan stories.

Delany: The original Conan series is as gay as ... In one sense I was just taking what I had already seen as there and bringing it to the surface because clearly it seemed to be already quite as gay as you could want. But they didn’t want it out there where everybody could see.

Brogan: Yeah. You also have a sizable queer readership today.

Delany: Yeah. And who are very happy with it, very happy.

Brogan: But do they ever ... I mean, what kind of relationship does that portion of your readers, do you think, have to the science fictional and fantastical themes of your work?

Delany: One of the things that has happened is that the gay readers among fandom are much more out, as is everybody else today. You know, now same-sex marriage is the law of the land. We have not, Dennis and I, haven’t been able to do that because up until fairly recently Dennis had no photo ID. We were only able to get that, he was only able to get that with Bill’s help and my help and the help of a number of other people, many of them on Facebook or at least some of them on Facebook. A genealogist named [unintelligible] Sprouse who was instrumental in getting him his birth certificate, which he had never had before. But all that. Which is one of the reasons I think Facebook has a place in all of this, although I also know people who don’t ever look at Facebook. Apparently Bill says the only time he looks at Facebook is when he’s looking at my account to find out what mood I’m in this morning.

Brogan: It’s funny to think about a technology like that or a subset of technology that has reshaped some of our lives so totally. For you, you’re not the kind of science-fiction writer who was working or has worked in an especially predictive terms for the most part. How do you feel as a science-fiction writer about having your life reshaped around this different form of networking, of relations, of relationality?

Delany: The technology that we’ve got is too complicated, so you get something like, whether it was MySpace or whether it was Facebook or whether it was some of the others. To come up with a platform that’s easier to handle or just Gmail or something like that because it makes things easier to deal with or do you do this on your iPhone or do you do it on a computer.

Brogan: Your phone.

Delany: My phone and that are ...

Brogan: Your computer.

Delany: … are basically the same thing. Fundamentally they’re the same thing. However, thumb typing is one thing and typing with eight fingers and using the thumbs for the space bar is another thing. You need several different bodily technologies in order to make use of them. The way the body interfaces with the actual object is one of the things that one is always dealing with and always dependent on.

Brogan: And it does seem like, not to return or to return to your work, it does seem like something, a peculiar and unusual way in which your science fiction often plays out, which is that it is whether or not it’s explicitly about queerness or what have you. It is work that is often about the body and it’s experiences. I think a lot, when I read your work, about the ways that you describe people’s bodies, the things that you’re attentive to. One of the personal predilections that shows up, I think, in a lot of your work is attention to nail-bitten fingers, for example. Is it fair to say that your own desires, your own thinking about the body plays out in the way you write and the kind of things you write about?

Delany: Absolutely, yeah. Absolutely, yeah. I have a sexual fetish for guys who bite their nails. I’m usually safe in the same room with them. It’s been there since I was nine or ten years old. I was always ... before I knew I was sexual. I was curious about my best friends in elementary school, Robert and Johnny, and Michael Held and what have you were all the nail biters in the class. I didn’t even know what it was, in a sense. It had something to do I think with the fact that I had sexualized the hands. My father had clubbed fingers and did not bite his nails. It was something about coming up with something that made the hands very different from his. It was a displacement, somehow. My father was not circumcised; I am. That was another thing, a sexual difference that was important. The foreskin, when it is forward on the penis, looks a bit like the shape of a nail that has been bitten. There were all these things that have to do with it, that connect with it.

Brogan: Was there a moment when you said, “I’m just going to write about this stuff, these personal desires, this personal attention to body in my fiction”?

Delany: Yeah.

Brogan: Was that a conscious choice for you?

Delany: That’s always what I wrote about.

Brogan: OK.

Delany: That was what I wrote about. I started by writing my masturbation fantasies down in notebooks. My mother found them in the bottom of my underwear drawer and took them to my therapist, who, I was seeing a therapist. I did not like my therapist at that time. I had a therapist whom I did not trust, I didn’t like. I had very much liked the therapist I’d first seen, a woman named Dr. Green. I liked her and I thought she was going to be my therapist. I was all ready for it and then she assigned me to somebody else who smoked a cigar, which used to turn my stomach. This is 1948 in a nutshell. Because he was so masculine and I needed a model for masculinity, so that’s what they would do. Basically, not because he was a good therapist, because he smoked cigars and was—

Brogan: Nothing more masculine than sticking a big ole cigar in your mouth.

Delany: Right, absolutely. I’m still not too hot on ... I like bears, but I’m still not too terribly hot on cigars. In fact, I’m definitely not hot on cigars.

Brogan: So you found your own way to masculinity.

Delany: Right, exactly.

Brogan: Of a different kind, perhaps.

Delany: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Brogan: One advantage of science fiction arguably is that it allows us to imagine the world otherwise. When you were writing about this stuff, about your masturbatory fantasies, about the particularities of your desire, what have you, in science-fictional forms, was there any conscious attempt there to think about a world that might be more amenable to your particular desires?

Delany: Sure, yeah. Who doesn’t? I mean, I’ve always assumed that probably Marx basically had some kind of fetish for workmen, which is why he wanted more of them in the world and for them to have a better deal because probably he thought they were, you know, at the very least, good-looking people or basically good people.

Brogan: So we all write maybe about what we want.

Delany: Yes, exactly. Yeah.

Brogan: Yeah. Your work, though, if it is allowing you to imagine a more desirable world, it’s not typically utopian. I think you did once use the word “pornotopia” to describe one of your works.

Delany: Right, mm-hmm (affirmative).

Brogan: And you’ve also used the term “heterotopia,” a concept that comes from Foucault, suggesting a place of difference.

Delany: A place of difference and it is also a medical term that has to do with moving flesh from one part of the body to the other. A sex change, for instance, is a heterotopia.

Brogan: In fact, in the novel that I’m referring to, Trouble in Triton, it is a science-fiction novel that deals with sex change.

Delany: Sex changes, yes.

Brogan: Yeah. Does any of this stuff, this need to imagine these alternate configurations of the world, has it grown less urgent for you as the world has changed?

Delany: For me personally, possibly. I think it’s gone much more urgent for the rest of the world. Which is to say, we are in a really strange state right now. The future does not look terribly good and anything from global warming to ... I just posted seconds before you got here three articles on the possibility of worldwide famine because of what’s going on in everything from what’s ... I just found a new term for it, “insectagone,” where the huge fall in the number of insects and pollination, pollution. There’s the pollution problem and then there’s the pollination problem, they’re getting out of hand. The animal farming and the rage for meat is not doing well for the environment at all because it’s making it harder and harder to grow vegetables and vegetables right now are what we need.

Brogan: Do you think of this kind of ... Maybe this is too aggressive of a word, but this kind of doomsaying as a sort of science fiction, or is it just fact now?

Delany: I don’t know whether it is just left over chiliastic panic, which is to say around the turn of the century there’s always a ... And we just came into a new century a mere 17 years ago and we may have 20 years of just general ... Or we may be doomed. We don’t know. I’m 75. I don’t know what’s going to happen. I hope I last another five, ten years. I have good genes in the family. I have a number of 100-year-old-plus relatives. I can remember thinking that I wasn’t probably going to be here too much after 60. Suddenly here I am 75 and possibly will be here a little while. The last first cousin that I had, the oldest first cousin that I had who was 96, male, just died a couple of months ago. Maybe I’ll make that. I have no idea what sort of mental state he was in. I think he tended to drink too much even at 96. The picture they had of him posted on Facebook, he was clutching a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, which is interesting because one of the last pieces of gay porn I watched there was a very good-looking young man sitting on a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, as it were.

Brogan: You really mean “sitting on”?

Delany: Sitting on, yes, yes. And taking it up his butt.

Brogan: Yes.

Delany: Where is it? I believe that’s the one .

Brogan: To the Last Man.

Delany: To the Last Man, yes.

Brogan: If you need the title.

Delany: Yeah. It’s in two volumes.

Brogan: You’ve written pornography. Do you take inspiration from watching porn, from looking at other people’s fantasies?

Delany: Some, although I’ve always been much more involved in reading. Porn in general doesn’t really ... I mean I went for a period where I bought a lot of it. I’ve had this for 8 years.

Brogan: This movie, To the Last Man?

Delany: And just got around to watching it last night.

Brogan: Was it worth it?

Delany: It was sort of, “Oh, that’s what it’s about.” I do not know whether I will ever go back to it again.

Brogan: OK. You talk about writing on ecological themes. Now you’ve also written some ... I think just yesterday you posted a memoiristic reflection that had you returning to the scenes of some other earlier memoiristic writing that you’ve done. Do you see yourself writing more science fiction as you move ahead?

Delany: I don’t know. My last short story, which is over there next to Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, which came out in the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction is a science-fiction story. My next book that’s coming out is not science fiction at all. It’s something called The Atheist in the Attic. It’s a reconstruction of a conversation between Leibniz and Spinoza back in 1776, I think. 1676, not 1776, was our ... No, 1676.

Brogan: Does philosophy play an important role in your reading and writing life?

Delany: It has in the past. Yes. I was a philosophy reader and I read a lot of Quine and Derrida. Those were philosophers that I ... And a number of others as well.

Brogan: Your work, even your ...

Delany: And Spinoza. I went through a whole big Spinoza ... Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders is a ... The philosopher of the book is Spinoza.

Brogan: In your other fictional writing as well, you often cite sometimes unexpectedly post-structuralist thinkers like Carole Jacobs, who was a teacher of mind.

Delany: Carole Jacobs was a ... Say that again.

Brogan: She was a teacher of mine and I believe a high school friend of yours.

Delany: Yes, yes, yes. I was going to say, I was friends with Carole in high school. Isn’t it a small world?

Brogan: It is.

Delany: She and Henry, her husband ...

Brogan: Henry Sussman, yeah.

Delany: Yeah, Henry Sussman, helped me get my first job. Was it my first job? They were there at SUNY Buffalo when I got there. It was really nice.

Brogan: So you’ve always been a reader of philosophy and academic theory.

Delany: One of the reasons I got hired is because I had read all the academic theory at a point when the only people who were reading it were the people at Yale because that was the center of academic theory. But you went to an ordinary English department in an ordinary college and they didn’t know who all these people were.

Brogan: We’re talking about the mid-’70s now.

Delany: Yes.

Brogan: The French theory made its way in force over the United States in the early ’80s. You are a longtime reader of this work. You’ve taught it, I think.

Delany: Yes, I have.

Brogan: You’ve certainly written critically about it. Do you see your fiction as theoretical or philosophical in its approach, its method?

Delany: Other people do. Other people do. I just got some ... No, not that one. But I did get an award for philosophical fiction a few years ago. I don’t think I ever got the actual plaque for various reasons.

Brogan: Would you put it up if you got it?

Delany: I probably would if I did get it, yeah. That’s an award, that clock over there is an award.

Brogan: A very complicated clock.

Delany: Yes, a very complicated clock from Caillou, which is an African American journal. Yeah, I probably would.

Brogan: Yeah. You’re listed on the editorial board of a publication called GLQ.

Delany: And those boards don’t mean anything.

Brogan: Of course, right.

Delany: They realize that’s just your name.

Brogan: So one of our recent guests, Elizabeth Freeman, was, until I think just this month, actually, or just last month, the editor of GLQ for six or seven years. Are you still steeped in that kind of academic discourse?

Delany: I do not keep up with it, I just don’t. There are not enough hours in the day. As I said, my reading in general has just become harder and harder for me. I try to keep up with people like Steven Shaviro and what have you. Basically I’m much more likely to keep up with my friends, try to read the stuff that my friends are doing, whoever they happen to be, than to keep up the way I did 25 or 30 years ago when I would ready every issue of EL French Studies from one end to the other. The result is that I made some friends from doing that, Jane Gallop and people like that.

Brogan: Important critics, all of them. To return to a practical question, you said earlier that you can make more money talking about science fiction in some cases than writing about it. If I may ask, how do you make money today for the most part? A few of your books were pretty significant bestsellers in their time. Dhalgren sold over a million copies and I’m sure still sells reasonably well for a book of its age.

Delany: Yeah.

Brogan: Other works of yours have more cult status. The vast majority are still in print, I think.

Delany: Yeah, which makes me feel very lucky.

Brogan: Yeah. Do you make money from your writing, if I can ask that impolitic question?

Delany: No. Well, yeah. I make some money. I still, yeah. I have the same agent I had when I was 23. I’m a faithful guy. I tend to hold onto ... If I lock onto someone and I like them, I try to stay with them. With the result, as I said, I wonder my agent, who is a year older than I am, that he’s still going. I don’t know how strong he is going. I assume he is. We people on this side of 70 often do things like die. If, for instance, I get a call at some point and I hear that Henry is no longer with us, I’m not sure what I’m going to do, getting used to a new agent. Henry himself makes most of his money from films these days. I don’t even know how many literary clients he has. He produced The Bourne Identity films and things like that. That’s where he makes a lot of his money. I asked him, I said, “Why do you keep me on, Henry?” He said, “You give the place style.” I’m sorry. He said, “You give the place class,” is what he said, not even “style.”

Brogan: Do you feel that way about your work?

Delany: No.

Brogan: Do you class up the joint?

Delany: No, I don’t think so. No. I think I’m just there. About the width of my own work, I cannot know and you cannot tell me, which is what it comes down to. I have too many reasons to misunderstand you and you have too many reasons to just lie, for whatever good intentions. You want to make the old man feel good, or whatever.

Brogan: Let me ask this. Looking back on this 50-plus-year career, are you proud of the work that you’ve done?

Delany: I did as well as I did the things I could do as well as I possibly could do them. That’s all I can say. I have no idea whether they are ... As I said, I have no idea whether they work or not or whether they do. I have a few people who are very faithful readers. I have 500 friends but I only have 700 who follow me on Facebook. Of those 700 who follow me, sometimes I think it’s only 12 who really pay attention.

Brogan: I didn’t even know that I could follow you until recently.

Delany: There you go.

Brogan: Follow Chip Delany.

Delany: Well, that’s just it. The new platforms, you have to learn how to use those and if you don’t know how to use them, you’re screwed.

Brogan: As a science-fiction writer, do you ever feel that the future has gotten away from you?

Delany: I don’t think I ever had it. I don’t think I ever had the future. People tell me I’m the guy who invented the internet. A book of mine called Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, every once in a while somebody says that’s the book that invented the internet. I don’t know. I wasn’t trying to. I was just writing about something. Whether it’s at all true or whether it’s just hyperbole that ... Never believe your own hype. That’s the way to really screw yourself over.

Brogan: Thank you so much for talking with us today.

Delany: You’re most welcome.