The “How Does an Inaugural Parade Announcer Work?” Transcript

Read what Charlie Brotman had to say about presiding over the parades of 10 presidents.

Jacob Brogan

This is a transcript of the Jan. 20 edition of Working. These transcripts are lightly edited and may contain errors. For the definitive record, consult the podcast.

Jacob Brogan: You’re listening to Working, the podcast about what people do all day. I’m Jacob Brogan. This season on Working, we’ve been talking to individuals active in fields threatened by the Trump presidency. While we’re still on that beat and we’re looking forward to a lot more, we’re doing something just very slightly different this week. We’re talking to a guy named Charlie Brotman, who for 60 years served as the announcer for the inaugural parades of most of our U.S. presidents till this year, when he was fired by Trump’s people.

We wanted to talk to him a little bit about what it was that he did for all of those parades, and he led us through many of his activities, describing how he got involved in the first place, what he does during the parades themselves, how he entertains the audience, how he makes use of silence to good effect during his presentations. This guy is great. We hope that you’ll like listening to him as much as we enjoyed talking to him. He’s truly an American treasure.

* * *

Charlie Brotman: Three and four, and five and six and seven, eight, nine, ten.

Mickey Capper: You sound great.

Brotman: Sounds OK?

Brogan: All right, let’s begin. What is your name and what do you do?

Brotman: My name is Charlie Brotman, B-r-o-t-m-a-n. I’m 89 years old and loving it. My idea of growing older is wonderful. However, if I grow old, that’s shameful. Older is good, old is bad, and what I do? For the past 60 years, I’ve been the lead announcer for the presidential inaugural parade in Washington, D.C., and it’s been quite an experience. In researching, I find that I am the only announcer ever to do the parade this long.

Brogan: What did that involve? You’ve been announcing these parades since Eisenhower’s inauguration?

Brotman: Eisenhower, correct. 1957. I was the stadium announcer for the Washington Senators baseball team. In those days, they were the Senators, now they are the Nationals. As the stadium announcer, I also was the public relations. Any celebrity, especially presidents of the U.S., would be brought to me and I would take them literally by the hand into the dugout and the locker room, and introduce the president to all the players. Guys are guys, and the president was getting a kick out of all this and the players were getting a kick out of meeting the president.

In 1956, that was my first year with the Washington Senators, I did this with President Eisenhower. Now, I gave him the ball, and he threw out the first pitch, and the baseball season now officially starts. I thought that for about 10 minutes, the president and I were buddies. That’s my pal. The president.

Brogan: President Eisenhower. How old were you then? Twentysomething?

Brotman: I think I was 30. If you can figure that one up. If I’m 89 now, what would I have been?

Brogan: Sounds about right.

Brotman: Does that sound good? OK. That was a big thrill and I ran home to tell my wife how important I was. How excited I was and I was with the president. I’m introducing Mickey Mantle of the Yankees and nobody could do anything until I announced it. She said, “It really sounds exciting and I want you to tell me all about it but first, take out the trash.” And so I did. I mean, after all, we’re just husbands.

In any event, in November of that same year, November, the season was over and I got a call from a woman who says she’s calling from the White House.

Brogan: This is just after the election, I assume.

Brotman: Yeah. Of course, we’re talking about Eisenhower being in and in any event, she says, “You must have impressed the president because he’s got half of the White House looking for you.” I said, “Well, I did feel like we were friends and hit it off well. What can I do for you?” “Well, the president wants to know if you’d have time and interest in introducing him again.” “Wow. You’re talking about me introducing the president? By all means, it’d be the biggest honor I’ve ever had. Where and when will I be actually introducing the president?” She says, “Well, it’ll be in Washington on Pennsylvania Avenue, Jan. 20, 1957, and it’ll be very exciting. It’s a parade.” I say, “Well, I’m a native-born Washingtonian. That sounds like the Presidential Inaugural Parade.” She says, “Mr. Brotman, that’s exactly what it is,” and this is the statement that floored me and I’ll never forget it: “Mr. Brotman, you will be the president’s announcer.”

Gulp. “The president’s announcer in this parade?” “That’s right. Jan. 20, 1957, probably around 1 o’clock in the afternoon.” “I’ll be there,” and that was the beginning. I did it. They had a script for me. I had to ad lib in several instances but it went well. I thought, “Wow. This is an experience of a lifetime. Of course, I’ll never do it again, but this is spectacular.” End of scenario.

It’s now four years later and I get a call and they said, “I’m with the Kennedy group and I see by these little business cards that your name is down. You did it four years ago. We are brand-new. We’ve never been in a parade. We don’t know what a parade is. We really need help and yours is the only name”— and they had the index cards, no computers in those days—“and we’d like for you to come to the White House and let us pick your brain.” “Absolutely. Whatever’s left of it, you got it.” I went over and we went over everything that I could remember. I introduced the Kennedy group and it went really well and that was the end of that.

I thought that would be the end. For the next, well, total of 15 inaugural parades, is what I was called upon to do, which I did. Fifteen consecutive inaugural parades. How many presidents was that? Ten different presidents. My heavens, see how my memory is. Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon. Ford did not have a parade. You know, he filled in after Nixon had his problems. Then, Carter, Reagan, then, H. W. Bush, Clinton followed. Then, it was the son, W. Bush and last, but not least, President Obama on his two terms. That was quite a stretch and I was really excited looking forward to introducing President-elect Trump. That didn’t materialize.

I did get a call from the PIC, the Presidential Inaugural Committee, and they said they were going to send me an email. I said, “OK.” I tried for literally a month to find somebody who I could say to, “Hey. I have the experience and I’m eager to work with you and maybe I can even be helpful to you because you’re new at all these things.” I got the email and it says, “Mr. Brotman, I just want to let you know you are a spectacular individual. You’re to be congratulated for all you have done in the area of announcing and we want to honor you at the parade but this particular time, we have a new announcer.”

A new announcer. Why not me? I mean, my age is 89 but I’m far from dying and even up to this minute, I never received an answer. It was like—

Brogan: They never told you why they didn’t want your services?

Brotman: Never, to up this second. In time, having researched a little bit, asking questions, I find that the new announcer is Steve Ray and he was a volunteer for Trump and did a very nice job for him. Of course, Trump won the election and now—and I’m making this up, but this is what I understand—that Trump now says, “Thank you very much for a wonderful job you did. Is there anything I can do for you?” He says, “I have an announcer and I’d love to announce your parade,” and it’s like Trump saying, “Get rid of the other guy, whoever he is, get rid of him. We’re putting in my guy.”

Brogan: He’s rewarding the loyalists rather than the experienced.

Brotman: Precisely.

Brogan: Did they even reach out to you to consult about the particulars of putting a parade together in that way that Kennedy’s people did way back in ’61?

Brotman: No. I haven’t heard from them other than the email and my asking a lot of questions that I never got answers for.

Brogan: You’ve been listening to former inaugural parade announcer Charlie Brotman. In a minute, Brotman tells us about the difference between announcing a ball game and announcing a parade. He also talks about how he got started announcing ball games in the first place.

* * *

Brogan: Let me take a step back. Is there anyone, as far as you know, that has been involved with the parades for as long as you have?

Brotman: Nobody.

Brogan: You really know the history of the Presidential Inauguration Parade.

Brotman: Absolutely. Correct. I’m the only one in the world that has been associated with the parade this long.

Brogan: Thinking back to those very early days when you were working as a baseball announcer, how did announcing those first inauguration parades that you did, differ from announcing ball games?

Brotman: Not too different. It’s basically, “Ladies and gentlemen, now coming to bat No. 17, Mickey Mantle,” or “Ladies and gentlemen, now approaching the presidential reviewing stand, the United States Marine Corps Band.” Not too different. Announcers, disk jockey’s, on-air personalities differ from stadium announcing. Number one, if you’re on radio, you’re talking pretty good and it’s fast a little bit and everybody hears what you’re saying and you put your personality into it and it’s really exciting but if I were to say the same thing from the microphone at the parade or the ball field, it would be, “Ladies and gentlemen, it’s certainly nice to have you here.” You see how slow, how deliberate? The reason for that, the radio voice, you’re in the studio, there’s nobody around, and you’re using your personality and enunciation skills to get the message across.

At the stadium, there are vendors, there are people, the fans talking to each other. It’s very difficult. If you were to speak as a radio disk jockey, no one would ever understand what you’re saying, so I’m being even more deliberate now to give you some idea of a before and after.

Brogan: You have to kind of cut under all of that other dialogue.

Brotman: Absolutely. It’s not like you’re losing your personality or it’s not like anything is wrong, it’s just that I’m trying to reach you, that you can hear what I’m saying and understand it without, “What’d he say? Hey, who was that, what was the name of …” and that is one of the reasons that you slow down and you can still enunciate and make sure that the spectators, the fans, hear what you’re saying.

Brogan: Did you do any other training or was it just that preparation that you had from baseball that you brought to your first—

Brotman: I went to the University of Maryland for one semester. I found that I was a party animal, so I was learning absolutely nothing but having a good time. I had done some announcing of football games and I liked that, so I saw an ad in the newspaper that said, “For broadcasters, the National Academy of Broadcasting in Washington, D.C., on 16th Street.” I thought, “I think I’ll try it,” so I went there and unlike Maryland, where I learned nothing and felt out of bounds, I was really pretty good at broadcasting to a point I ended up teaching and they found me a job and I wanted to be a sports announcer. I ended up in Orlando, Florida, and just outside of Orlando, was Winter Park. That’s where the Washington Senators were doing their spring training.

I interviewed the players. I interviewed the owner, Calvin Griffith. He says, “Charlie, I understand that Washington, D.C., is your hometown.” I says, “Yes, sir.” He says, “Would you give any consideration of doing the stadium announcing?” I said, “Calvin, if I got that job in Washington, I would think I’d died and came to heaven.” He says, “Well, we got eight other guys who are auditioning next Wednesday and if you want to take a plane, take a chance, come on up. Whoever the best man, wins.” So I did.

Brogan: You won.

Brotman: I won. Ta-da.

Brogan: What do you think you brought to that first audition that won the day for you?

Brotman: Personality. That’s what I really think. I never thought I had a great voice. It’s OK, but it’s not terrific. I mean, I hear on radio on the networks these guys basso profondo, I mean, they were down in the basement with their voice and I’m not even close, but in any event, I think I was able to read what I had to read and explain things that I was asked to explain. I think that’s what really helped me.

Brogan: Once you started doing the inaugurations, how did that job change and evolve over the years?

Brotman: Well, first things first, going from the rooftop to underneath the, one floor down, so I’m on the third floor. Every parade, at the beginning, I was on the roof of the media complex.

Now, if I can paint a word picture for you, on the grounds is the White House. In front of the White House is the presidential reviewing stand. Then, there’s Pennsylvania Avenue and then, there’s a media complex three stories high. I was on the roof. Me and Secret Service, for security purposes. The first three years—Jan. 20 in Washington is very cold.

Brogan: Brutally cold, usually.

Brotman: Brutally cold. I am on the roof and I have my script and when it’s windy, I’m having a difficult time keeping the script together. If there’s any rain, it’s just out-of-sight. It’s ridiculous. After three years, I explained to the officials that I think I need something a little bit more encompassing, something that the rain or the snow or the wind don’t get to me, so they moved me to the top floor, so I went down one floor. That’s where I’ve been ever since.

Now, that vantage point is perfect for the announcer. He can see to his left, all the way down to the 15th Street or he can look to his right, all the way to 17th Street, and of course, 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., 16th Street is the White House.

They call me the president’s announcer and the reason for that, the president is actually situated streetwise very, very low and he cannot only see what’s in front of him. Can’t look to the left. Can’t look to the right. Doesn’t know who’s coming or who’s going. As the president’s announcer, he listens to me.

Brogan: You’re not just informing the crowd, you’re actually informing the celebrant himself.

Brotman: I’m actually the announcer for the president and several hundred thousand people are listening in. You’re absolutely right. It’s not for the spectators. It’s for the president. When I announce that the United States Marine Corps Band is now approaching the presidential reviewing stand, he knows when to stand, when to salute, when to take off his hat, when to sit. I’m a word guide for him and it’s worked beautifully for all this time.

Brogan: Which inaugurations were most memorable of the 15 that you did?

Brotman: For me, the first one always is memorable because it is the first time, but hardly one of the better ones. He was a military man and thought a pain. “I should be in the White House working. I don’t know why I’m doing this kind of stuff,” but that would be one.

The second one would be Kennedy because here we have a military man who couldn't care less and here comes Mr. Personality, here comes the high hat and society has arrived in Washington. What I have learned is that the parade is an extension of the president’s personality. If he’s a military man, straight, dull, that’s the way his parade is. On the other hand, like Kennedy, who’s surrounded by important people, social people, movie stars, and so forth, it becomes really exciting. That was the first exciting parade I’ve ever done.

The next best one would be President Reagan. Reagan pulled in half of Hollywood here because they were co-workers, they were friends. Now, I consider myself a very ordinary guy, and as an ordinary guy, being with movie stars, rubbing shoulders together, I mean, I was really impressed. It was exciting for me, too, and I think maybe it may have even generated a little excitement over the microphone and the speakers. That was exciting.

A couple of things happened, with Reagan, mostly. The second term for Reagan, it was so cold. It was like 20 degrees below zero, not below freezing. It was really cold and with that the president’s advisors told him that the parade itself should be canceled. No parade and we’re going in that direction until the president stepped in and he basically said, “We can’t stop this parade. All these kids have been waiting for four years. Their bands and cheerleaders. I couldn’t do this to them and I know we can’t do it outside. I recognize that. The marchers really could catch frostbite, pneumonia, and everything else, so we won’t even enter into that arena, but let’s do something perhaps in an arena.”

We had the Capital Centre, which was in a suburb of Washington, D.C., and a very nice arena where you played professional sports and college sports. I got a call 11 o’clock the night before and basically they’re saying, “Charlie, don’t go down to Pennsylvania Avenue. We’re not having the outdoor parade. We are having it at the Capital Centre. We won’t be able to bring in the Army Band that has maybe 300 to 400 participants, but we will do everything that we can to get all the kids to do what they do, so they can feel that the trip was worthwhile and they can tell their friends.” Without Reagan, this would never have happened but it did happen and I was the announcer. They told me, “Might as well throw away the script because it has nothing to do with what’s happening in this building.” So I was able to ad lib and basically just be a friend of the fan, the spectators, and it seemed to work.

Brogan: You’ve been listening to former inaugural parade announcer Charlie Brotman. In a moment, he talks about how he employed trivia during his presentations to keep things moving along even when the parade itself was coming to a halt.

* * *

Brogan: On a typical day, a typical inauguration day, when would you head out to the parade grounds?

Brotman: I get there about 8 o’clock in the morning.

Brogan: How did you usually dress on those days?

Brotman: Normally, it’s very cold and I do not dress for television, I dress for warmth. Thermal underwear, two pairs, and sweaters—

Brogan: Gloves.

Brotman: A lot of layers.

Brogan: Yeah. I imagine though that it was sweaty work. Would you have to pull clothes off as you went?

Brotman: In some areas and sometimes, yes. Absolutely, but it’s better to take off than to search out another sweater or jacket to put on.

Brogan: You said that each parade was a reflection of the respective president being inaugurated.

Brotman: Exactly.

Brogan: Was there, though, or is there generally a standardized script, anomalies, like the one at Reagan’s second inauguration aside, was there a baseline for how things went from one year to the next?

Brotman: Most of the scripts are similar. The participants in the parade are similar. They’re different but similar. I’ll tell you since we have a minute. Let me look at one of these things.

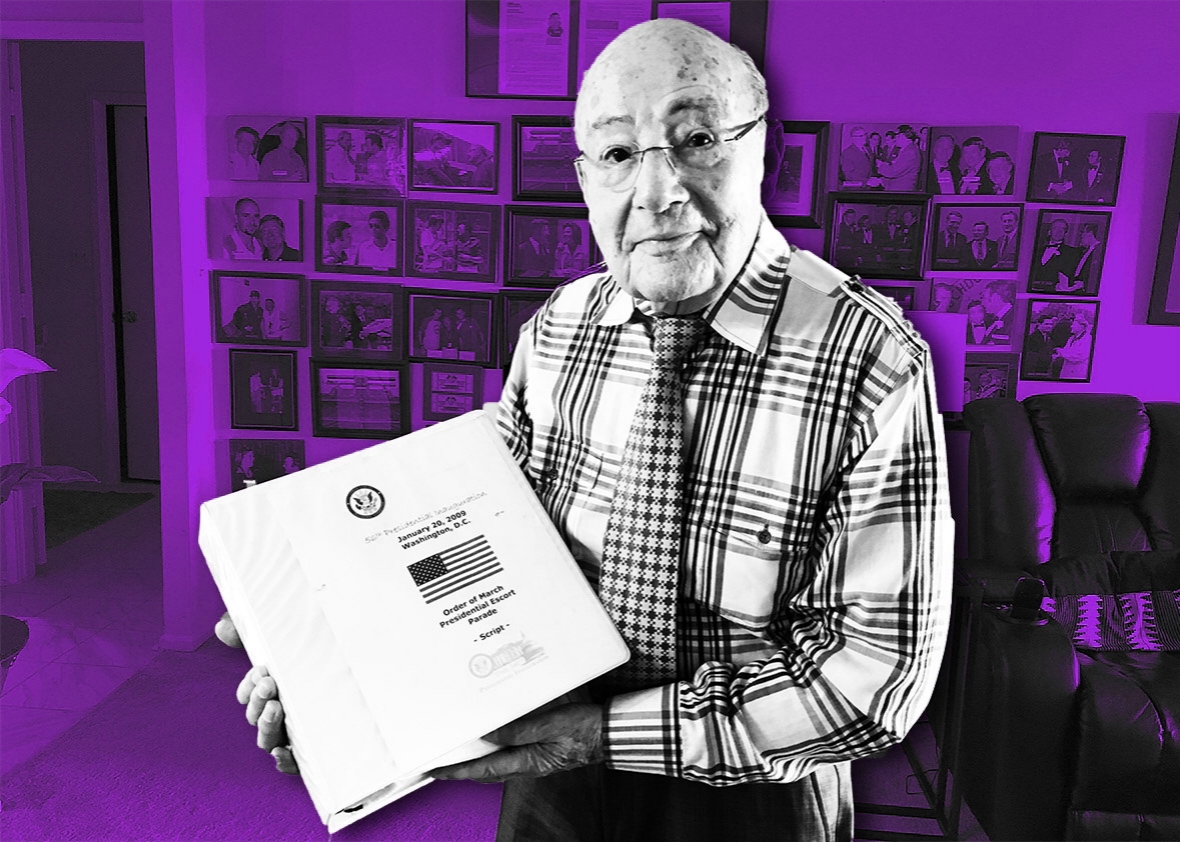

Brogan: Here on the table in front of us, you have the scripts in thick binders for most, 11 of the 15 parades that you’ve done over the years.

Brotman: For the folks listening who are over 50, these scripts remind me of the Yellow Pages of bygone days but they are heavy, like I don’t know, 20 pounds.

Brogan: They look it. Yeah.

Brotman: What do you think?

Brogan: They’re substantial.

Brotman: Yeah. OK. Let me see. I’m just going to go through—

Brogan: Which script is that that you’re looking at there?

Brotman: This one is Bush. “George W. Bush is the 43rd president-elect of the United States. Formerly the 46th governor of the state of Texas, Bush has earned a reputation as a compassionate conservative who shapes policy based on the principles of limited government, personal responsibility, strong families, and local control.”

Brogan: This is what you would read as it begins?

Brotman: The easiest thing to do: show up 10 minutes before the march, open up the script, start reading. Nothing exciting. Close the script, go home. I don’t do that. It’s just not my style.

Brogan: Who writes that script, though?

Brotman: The PIC. Presidential Inaugural Committee have people who write it and what they have done, they must have broadcast background because they would put something like a full-page, eight and a half by eleven, and some single space, some double space, that would take—if I read it as I normally would—about a minute and a half.

Now, if I read that introduction of the band in front of me for a minute and a half, I would miss two or three units. That is much too long. Twenty seconds is all I need, and then they have now passed the presidential reviewing stand, next group is on top of us. So I explained that to them and they did change from a full page to like 20 seconds’ worth because they know now that they’re writing too long.

Some of the things I try to do for the spectators, the fans, the idea of the announcer, in my opinion, is to inform and entertain. By that, I don’t mean you have to tell jokes or sing or dance or any of that but there are areas, as a for instance, when you’re talking about a parade, any and all parades have a little problem now and then. A flat tire, somebody gets sick, whatever the minor thing is, but the parade stops for about five, ten minutes.

At the beginning, there’s nothing I can do. I mean, a flat tire, I’m not going to go fix the flat tire for them. We have no background music, so there was silence. I’m thinking, “I can’t let this happen like this, but what can I do?” I’m thinking and nothing, nothing. I didn’t do anything. I was angry at myself for not thinking quicker. I didn’t want to tell jokes so I did nothing.

Since that time, I’ve come up with a few things. One of them has to be trivia. What I’m normally saying is, “Ladies and gentlemen, there’s been a delay in the parade but that doesn’t mean we have a delay in having fun. I’m going to ask you some questions. Now, this is going to be a trivia contest, nobody’s going to win a million dollars, I’ll tell you that right away. What you will win? Bragging rights in front of your family and friends.” Let me give you an example. “The White House. How many restrooms do you think are in the White House? A hundred? Two hundred? Three hundred? What is your guess?” I’ll wait for about 15 to 20 seconds.

Brogan: I’m going to say 200? That seems like a lot. We’ve been there a few times.

Brotman: What I like to do is, “Who said 200?” Then everybody was saying, “Wrong,” and I get that reaction. I mean, I’m looking for that reaction. It’s 320-some. I would not like to be the cleaning lady at the White House.

Brogan: We tried to interview her.

Brotman: These are things that I’m saying to the crowd. There’re several hundred thousand people out there and, “OK. Did you get that one? Well, if not, I’m going to give you one more.” Then, I’ll do one or two more and, “Hey. Good news. The parade’s about to start again. Now here comes the Marine Corps Band.” That type of thing.

Brogan: When all of this is going on, how much of what you’re doing is dictated by just what you see happening out on the street and how much of it is being fed to you through an earpiece or something? What information streams?

Brotman: Nothing is being touted to me. Nothing’s in the earphone. I’m the lone eagle, I do what I do. Nobody says do it or don’t do it and I’ve been doing this for 60 years and they don’t care if I’m a Democrat or a Republican or Ubangi, whatever it happens to be. I’m just me doing what I think is informative and entertaining. And it seems to work that way. It’s worked that way for—

Brogan: Sixty-some years.

Brotman: Sixty years. As a for instance, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, you’ve heard of them, of course, and it was Reagan who had the choir as a special guest. As the cherry on top of the whipped cream that the Tabernacle Choir was, they were last. The problem was they had waited too long to start the parade. It was a slow parade, had many, many different groups in the parade and it continued until about 5:30.

Now, 5:30 in Washington in the wintertime—

Brogan: Dark.

Brotman: —is dark, which meant that when the Mormon Tabernacle Choir crossed in front of the presidential reviewing stand, you could hear them but you could not see them. It was such an embarrassing situation. There were no lights down there. This is a daytime parade and I am the announcer. I can’t turn the lights on. I can’t pull the sun down, so I would try my best with words. “Ladies and gentlemen, this is the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and they are now approaching the presidential reviewing stand. I know that, unfortunately, no one here can see them. It’s pitch-black.” Then, for effect, I would have silence. The biggest underlining, as you guys know, if you’re on radio: silence. It gets your attention because they are used to hearing something, and when there’s nothing, “Is it me? Is it my ears? Did they stop?” Then you come back with what you want.

That’s what I was trying to achieve there. Since that time, they’ve put up a spotlight just in case it goes long. Those are some of the changes.

Brogan: What were the most difficult parts about announcing the parades over the years?

Brotman: The one thing I remember is that there are interns and interested young people wanting to get experience and an opportunity maybe to experience announcing at a presidential parade. I remember, I would have to say this was maybe 20 years ago, I had an individual who was an intern ask if there’s a time when, an opportunity, could they stand in and read an announcement. I said, “Sure. Look, how about right now because I need a break. I have to go to the bathroom and I’m going to give you the microphone and here’s a band coming now. You get next to that microphone and I’ll be downstairs and then I’ll relieve you of your microphone, but for right now, introduce the band.”

The guy’s all excited. “Ladies and gentlemen, now advancing to the presidential reviewing stand, the United States Marine Corpse Band.” Gulp. I immediately made a U-turn. Didn’t have to go anymore. Scared me to death. I really thought that maybe people would think that was me and I cringed and I thought, “I’m not letting anybody on that microphone anymore.”

Brogan: No one else is talking.

Brotman: If I’m going to foul up, I want to be the one who fouls it up.

Brogan: Did you have any tricks to make sure that you pronounced names of dignitaries and such right, normally?

Brotman: I check, and I learned this from baseball. When you’re talking about some of the baseball players, they’re from all parts of the world and pronunciation is difficult sometimes. What I have always done in sports is to go to the individual and say, “How do you want me to pronounce your name?” I would say 99 percent of the time it was, “Oh, just Americanize it,” or “Just anything you say is OK.” I’d tell them, I said, “I’m not going to pronounce it like you. I’m not a gifted foreign language guy but I’d like to do it as close as I can.” Then, they would try to do that.

I try to do the same thing at the parade. I’d look through the script and then I get some of the people who put the script together, “How do you pronounce this?” “Oh, that would be …” and then he would tell me and that’s what I would use.

Brogan: What will you miss most about announcing the parades live?

Brotman: Announcing the president of the United States, no matter who he is, he is the president of the United States and I’ve always been so absorbed with announcing this infamous person and I will miss that. Also, in the marching units themselves in the parade, sometimes I meet some of the individuals and I make a point of announcing their names and they get such a thrill. I know here in Washington, I announce the mayor who will be in the parade and I see the mayor from time to time. “Charlie, way to go with that announcement. That was terrific.” I miss a little of that.

I have friends and family who listen on the television. “I heard you on the background,” so it’s a kick so I will miss it to some degree. I’m going to try and use it. I have been retained by the WRC-TV Channel 4 in Washington. They contacted me and says, “If you’re not going to be the announcer at the parade, we’d like for you to be the announcer at Channel 4 NBC.

Brogan: You’re still involved in some way? Well, you are a huge part of this history. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us today.

Brotman: Thank you for inviting me. It’s a delight, really.

Brogan: The delight was all ours.

Thanks for listening to this episode of Working. I’m Jacob Brogan and I have never marched in a parade. We’d love to hear your thoughts about the podcast. Our email address is working@slate.com. As we’re recording this, we’re in the very last week of President Obama’s tenure in the White House. We would encourage you to go back and listen to some the many episodes that we recorded with members of his staff and other people who work around the White House. Find out what it was like to work in that environment in its final days.

You can listen to past episodes at Slate.com/working and we would love it, especially if you like the show, which we hope you do, if you would rate and review it on iTunes. Working is produced and edited by Mickey Capper, who also wants you to rate and review the show and also hoped you like it.

Capper: Yeah. It just takes a minute and it helps the show a lot. Review the show.

Brogan: Our executive producer is Steve Lickteig and the chief content officer of the Panoply network is Andy Bowers.