Why Angels in America Still Resonates

Slate’s Dan Kois and Isaac Butler discuss the groundbreaking play’s cultural impact.

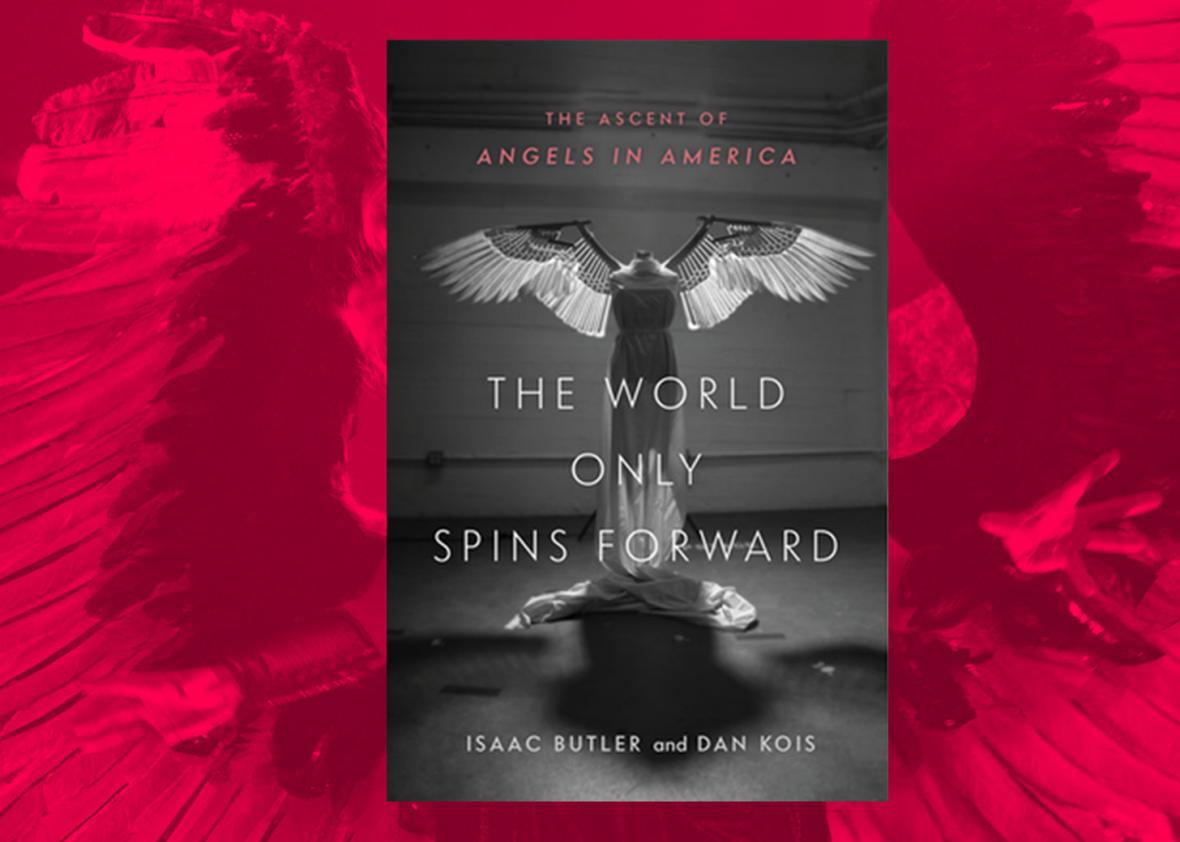

Photo illustration by Slate. Images by HBO and Bloomsbury Publishing.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the original Broadway premiere of Angels in America, a groundbreaking play by Tony Kushner that helped to change representations of gay people in culture. Written and set in the Reagan era and during the rise of the AIDS epidemic, Angels in America became renowned for being a life-changing experience for those who saw its various productions.

Slate’s Dan Kois and theater director Isaac Butler first explored the background and phenomenon of the Pulitzer Prize–-winning play in an extensive Slate cover story in 2016. They’ve now expanded that oral history in their new book, The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels in America. In this S+ Extra podcast—which is exclusive to Slate Plus members—Chau Tu talks with Kois and ButlerButler and Kois about the play’s history and why they think it still resonates today.

* * *

This transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Chau Tu: Let’s offer a little background for those who may only be partially aware of it—what is Angels in America?

Dan Kois: Angels in America is a two-part play by Tony Kushner that won the Pulitzer Prize in 1993, and the Best Play Tony in 1993 and 1994. It’s set in the late ‘ ‘80s, mostly among a group of gay men in New York, including both fictional ones—a gay man with AIDS, his lover who leaves him, a closeted Rrepublican judicial clerk—and real ones like Roy Cohn, the ‘‘80s-and-earlier-era power broker in New York who was also a compatriot of Joe McCarthy’s. The play was quite a sensation when it premiered—it really changed the conversation around how gay people are represented in culture and also about how AIDS and illness were generally treated by the culture, and it is now being revived on Broadway this spring in a transfer from the National Theater in London starring Andrew Garfield and Nathan Lane.

How did you first become familiar with it?

Isaac Butler: I think Dan and I both had that experience when we were younger of seeing both parts of Angels in America on Broadway—there are a couple of different ways you could do it: You could marathon it in one day or you could see one part one day, one part the other. And both of us I think definitely had that experience of having heard for a long time that this very, very important life-changing play was coming, sort of very highly anticipated. Then when it arrived, it was this huge sensation the way that Hamilton is a sensation, or the way that August: Osage County was a sensation a few years ago.

We both went to see it when we were students and we both had this just incredibly profound experience that I think an entire generation of people who do theater had, which was seeing both parts of that play and actually feeling your entire being be transformed by the experience.

And that the play had almost defined for you what your mission as an artist and human was going to be from that point on. I mean, it sounds crazy when you describe it, but for a whole generation of people seeing Angels in America, there really was like a who you were before you saw it and who you were after it and we both had that very profound experience.

Kois: That’s what a seven-and-a-half-hour day in the theater can do to you.

So what brought you to writing this piece for Slate?

Kois: So it was a cover story that ran in June of 2016. I’m an editor at Slate and each week, we have these cover story pitch meetings in which all the editors get together, usually with a bunch of invited guests from the staff writers and editorial assistants and other people on staff, and we pitch ideas for our cover stories.

The mechanism may be of interest to Slate Plus listeners or not, but the mechanism is actually stolen from a magazine called ClickHole, which I profiled for Slate in 2016, in fact. The idea is everyone sends in these pitches anonymously, they’re compiled into a document, everyone reads the document before the meeting and then at the meeting, people bring up the pitches that seem most interesting to them, but you’re not allowed to pitch your own idea. Other people have to support your idea and pitch it.

And so I wrote up this pitch for our cover story’s meeting, and put it in because the 25th anniversary of the very first production of Angels in San Francisco was coming up at that point, and I had always been fascinated by the story of the play. I had this sort of vague sense that it had a stormy history but I didn’t really know that much about it, but the more I looked into it, the more it seemed amazing.

I wrote up this pitch and walked into the meeting—, was very nervous that no one would care about my pitch and would fade away into the ether. But in fact, Julia Turner, the editor -in -chief at Slate, brought it up in the meeting because she had also had a similar ecstatic experience with Angels when she was younger. For her it was a production at Yale where she went to college, but also it sort of changed her artistic world view.

So her supporting that in the meeting meant that we had a green light to sort of go ahead and I brought Isaac on to co-write the piece with me because it was way too big for one person to do all by himself. And the more that we wrote and collected up these stories from all the people we wanted to interview, the more we realized that A) we wanted to tell it in an oral history form because so much of Angels is about voices in dialogue with each other, and to write the story of what we believed to be the greatest play of our age, it seemed like oral history was the way to go, a. And B) that it was a book, that after the story ran, if people liked the story, and we felt like we could get traction, we should absolutely do a book because, for example, the first draft of the story was 50,000 words long. Which, for listeners who may not know, is too many words for a magazine.

Butler: I think the eventual article that ran, which was also a substantial, like, very long article, was 15,000 words or something like that?

Kois: Yeah, we ran it at 15,000, which is way longer than almost anything else we ran on site that year. Or ever. Happily, when we published it, it did really well. People really sparked to it, it turned out there was, as we suspected, an entire generation of people—both people who make theater and just people who love theater and just people who love art—who had a similarly galvanizing experience with Angels sometime in their life, whether it was reading it or seeing it on Broadway or seeing it in a regional production, or seeing the HBO movie which came out in 2003. Many, many people had had that experience and said the story was good enough to carry them through it. And so then we turned it into a book and here we are.

So let’s just step back a little bit, I mean you’re talking about all these like personal relationships to this play and this story. What struck you about this story? Why were you guys so attached to it and what kind of brought you to it?

Butler: I would say that the thing that kept coming up for me was the way that the play and the story of the play are about the same things. They have similar themes., Tthere’s a similar messiness to both of them. The play is about the end of the Cold War and Reaganism and the AIDS crisis and who we are as a people and the necessity, the painful necessity of change. And it’s about life and death and love. It’s about these huge, huge things in a very specific, particular way.

And the story of the play turned out to be that too. You have people struggling to create art during the height of the AIDS crisis when all their friends are dying. You have this question that the play asks about what do we owe ourselves, what do we owe each other, and what do we owe to love. And that question every single one of our subjects struggles with at some point. That was the thing that was really striking to me. And that it is a play about change and that everyone who encountered this play was profoundly changed by the experience of doing it.

Kois: And also what I ended up loving about it, in addition to everything Isaac so eloquently explains, is just that it turned into just like this crazy rousing story of artistic creation in the face of being almost 100 percent clear that everything about this play was a bad idea. Like, it was too long and it was too big and then it wasn’t just one play, it was two plays, and they were seven and a half hours long in total, and they were about gay people at a time when you definitely could not get a mass market to see a thing about gay people. And also angels came down from hHeaven, and also the characters went up to heaven, and also a bunch of angels spoke in like gobbledygook, et cetera, et cetera.

And every theater that put this play on struggled with how to do it. Often the effort of putting this play on both defined these theaters for decades and destroyed them, put them out of business. And every step of the way there were artistic disagreements, and firings, and bitter arguments, and moments of great beauty, and it all like made this sort of like dramatic story of the creation of an amazing thing that at almost any step of the way could have easily just been discarded. You know, Tony could have never had the idea, or he could have had the idea and discarded it or maybe he never gets the NEA grant that allows him to support himself. Or maybe not theater ever commissions it, or maybe after it’s such a total fucking disaster the first couple of weeks of rehearsal, they’re just like, “You know what? Screw this.”

But none of those things happened., Iinstead, everyone was so moved and touched by the play and so driven by the urgency behind what it was trying to do, that they like gave it a shot. And the show kept going on and it eventually evolved into this generational defining work of art.

So now you have a book about it. Obviously this was coming from the article, so what did you expand upon from the article in the book?

Butler: Well, we expanded upon everything. There is more about everything that you’ve read in the article. There’s more about the making of the movie, including a failed attempt to make the movie with the director Robert Altman. There’s more about the development of the Broadway production and of both parts we get into some stuff involving the contract negotiations after it’s a hit. You know, there’s more every step of the way.

And then on top of that, there are dozens of stories that we didn’t have room to tell in the article that we finally have room to tell, everything from this production in North Carolina that the state government tried to shut down, to the behind- the- scenes story of the production that’s about to come to Broadway. And in addition to that, we spent a lot more time talking about like the social context and the history that gave birth to the play—which is to say, the growth of gay rights movement, the unfurling of the AIDS crisis, the Reagan revolution. Eventually the rise of the religious right, you know, the context of the play gets greatly expanded upon as well.

You did upwards of 250 interviews for the book, right?

Butler: Yeah.

Kois: But it only felt like 1,000.

Was there anyone that you didn’t get to speak to and you wish you could have?

Kois: Sure. Well, a lot of people are dead.

Butler: Yeah, that was the big one for me, was people who had died. There’s a guy named Rick Frank who played Roy Cohn in one of the very first workshops and was ill with AIDS while doing it and died not that long thereafter. I would have loved to have talked to him, for example.

Kois: And even some of the execs who sort of oversaw this throughout its creation. For example, Gordon Davidson, who ran the theater in Los Angeles that put on the first full production of both parts of Angels in the United States, died actually just shortly after our piece ran but before we got a chance to reach out to him for the book.

What else was really difficult about putting this together? I mean, it just seems like there’s just so much content and there’s so much.

Kois: I don’t know, I didn’t think it was that difficult. I mean, this is like maybe a weird thing to say on a thing about making a book. But like, it was a lot of work and there were a lot of interviews, and there was a lot of text to wrangle, but it wasn’t like hard or un-fun, you know.

You were interviewing people telling stories they loved that they’ve been telling their whole lives or saving up to tell their whole lives about formative, artistic, and political experiences that they will never forget and putting them together in this collage of voices was like pretty much a joy.

Butler: And I’ll also say that there’s a thing that we talk about in theater sometimes that can sound a little loosey goosey about the—

Kois: A little woo-woo.

Butler: A little woo-woo, yeah, that the work itself has its own needs and desires of what it wants to be and like a lot of your job is to listen to that and to fulfill that to the best of your ability. And, I haven’t always felt that on every play I’ve worked on, every piece of writing I’ve done, but I think we both really felt that and talked about it a bit over the course of creating this book. That the play or the story would kind of tell you like this is what I need and you would go out and you would endeavor to the best of your ability to give it that. Which is also a way people talk about doing Angels in America.

What do you think was the most surprising thing that came out of the reporting on this for the book?

Butler: We were talking about this the other day that one of the really fascinating things about this play again is, you know, this is a play about change and to engage with it is often to be changed by it. Particularly when you’re spending months and months and months working on it. And one of the fascinating aspects of that is the number of people—it’s not a lot but it’s enough—who encountered this play as actors and then by the end of doing the play, weren’t actors anymore. They weren’t traumatized by it, it’s just that by the time the play was over they were like, “Oh, I’m not sure what I was called to do on this earth was being an actor.” Or, “Oh, I don’t think I will ever do anything this great.” This is a moonshot., Yyou get it once in your life.

Joe Mantello became a highly acclaimed director and went on to direct Wicked; David Marshall Grant became a writer and producer and now does Code Black. One of the people who played the Angel is now a therapist. So that was really interesting to me as someone who sort of shifted what I want to do in my career over time and stuff, the way that these people encountered this play and were transformed by it.

Kois: Yeah, right up to a guy who did the play just like two years ago in Bethesda and then decided after that he didn’t want to act anymore and now he’s a political activist. Like in the Trump era, he decided that’s what he needs to do with his life and the play helped convince him of that.

So it’s like a life-changing thing.

Butler: Yeah, absolutely.

Kois: Yeah, I agree with Isaac it’s heartening to hear that it isn’t just life-changing for the audience—it’s life-changing for the people who do it. Maybe more so. They’re living in this play for months as opposed to we who just get our seven -and -a -half hours with it.

I was surprised by so many things, but one thing that I do want to point out is that I was just really surprised by this whole sort of shadow version of Angels in America movie that could have existed had Robert Altman managed to stop smoking weed long enough to actually do it. He optioned it., Aa studio optioned it with him a. As the play was premiering on Broadway, and he said that he loved it and he did a bunch of meetings with Tony., Tony wrote a whole screenplay for him, which we’ve read, which is fascinating. It was a game attempt to transform Angels in America into an Altman movie, with overlapping conversations and people having coincidental meetings on the street and stuff like that.

Butler: They had a casting idea, that Robert Downey, Jr. was going to be in it, and Tim Robbins.

Kois: Oh yeah. And they always wanted [Al] Pacino for Roy Cohn, who eventually was in it. But, you know, there’s this whole other version that might have had these younger sort of ‘ ‘90s-ish actors. They budgeted it, and then they cut the budget, and then they cut the budget, then they cut the budget again. And Altman had all these ideas about the Angel’s penis. He had this idea that he just loved that the Angel had this like multi-pronged penis that we would see multiple times in the movie.

It was just going to be wild, you know? But you know, then Altman made Short Cuts, which did great and then made Prêt-à-Porter, which did less great, then he made other movies that did even less great. Then he lost interest, and then he was like, “Tony Kushner, can you make this movie happen?” Aand he’s like, “I’m not a movie director, what are you talking about?” Then it like fell apart, and it’s a shame. Not that the movie that got made was bad—in fact I like it quite a bit—but think of this totally insane version of Angels in America that could have existed in 1995 is delightful.

Butler: I will say that in terms of research, one of the more gratifying things was going to Robert Altman’s papers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. They have an amazing collection of American film directors’ personal business papers. And going to his papers to read through the contracts that they all signed with each other, or letters that they wrote to each other, these scripts. You would expect this of someone like Robert Altman, but the folders with all the Angels in America stuff is part of two file folder boxes that are just Robert Altman’s never filmed projects that went to various states of completion and were abandoned. He was going to make an Amos and Andy movie—

Kois: So bad.

Butler: Yeah, it’s such a terrible idea. So that was like a really gratifying thing to have this angle into an American master’s work. It was really fascinating.

So, it’s the 25th anniversary of the Broadway premiere this year and the play is also returning to Broadway this month. How do you think the play still resonates today?

Kois: Well, there’s like some very obvious ways, and then I think there’s some more complicated ways. The obvious way is that I think for a long time, it was easy for many Americans to sort of put aside the Reagan ‘ ‘80s and feel like we as a culture, you know, that our arc was bending towards justice as we all hoped it would. And then suddenly it’s not, and suddenly we have a president who was not particularly interested in the arc of justice. And, we have a president who in fact is looking for his own Roy Cohn, as he has said in the fucking Oval Office.

And here we have a play that for many people remains the sort of defining image of Roy Cohn and that, on top of everything else it did, seriously investigated the sort of cancerous role that Roy Cohn and his particular brand of vicious conservatism had in American life. So there’s the obvious way that it resonates, right?

Butler: Yeah, I totally agree. I would say another thing, which is there’s an odd thing with this play where by the time it premiered on Broadway, George H. W. Bush was out of office, Clinton was in, and the gay rights movement was, you know, accelerating in power. It would suffer some setbacks like the Defense of Marriage Act, but there was this sense that this play was the crest of a wave.

But that is not the circumstances under which the play was made. The circumstances under which the play was made was the height of the AIDS crisis, the height of Reagan America, that’s when it’s set in the late ‘ ‘80s. But that’s when they started making it too; that’s when Tony did most of the original writing of it. And so now that it’s returning to Broadway, we are living under circumstances far more similar to how they were when the play was created than the original Broadway audience was when it came to Broadway.

Kois: That’s really interesting, I hadn’t thought about that, but that’s totally true, right? That like, you know, there are all these stories about even in the L.A. production, which premiered right around the time of the presidential election that Clinton won, and then the Broadway production happened just after Clinton’s inauguration. There was this sense that everyone had of being part of this sweeping moment of change and like this relentless optimism about the future which the play really encourages, even among its sadness and difficulty. And so to have that same play appear now at a time when many, many people—even Tony Kushner, the person who wrote this play—are feeling like beaten down by history has a very particular meaning. I think that this is going to be really interesting to explore in the next couple months as the play appears.

Thank you for talking with me today.

Butler: Thanks.

Kois: Thanks, and I hope Slate Plus listeners really like it. Slate Plus, as it always does, helped make this project possible in the first place. Without Slate Plus, I don’t know that we’d necessarily have the cover story initiative. Without the cover story initiative, we wouldn’t have this story and we wouldn’t have this book. So good job, Slate Plus!