A Women’s Right to Choose Returns to the High Court

In Justice Scalia’s absence, a newly balanced Supreme Court gets heated up in a fiery, female justice–fueled debate.

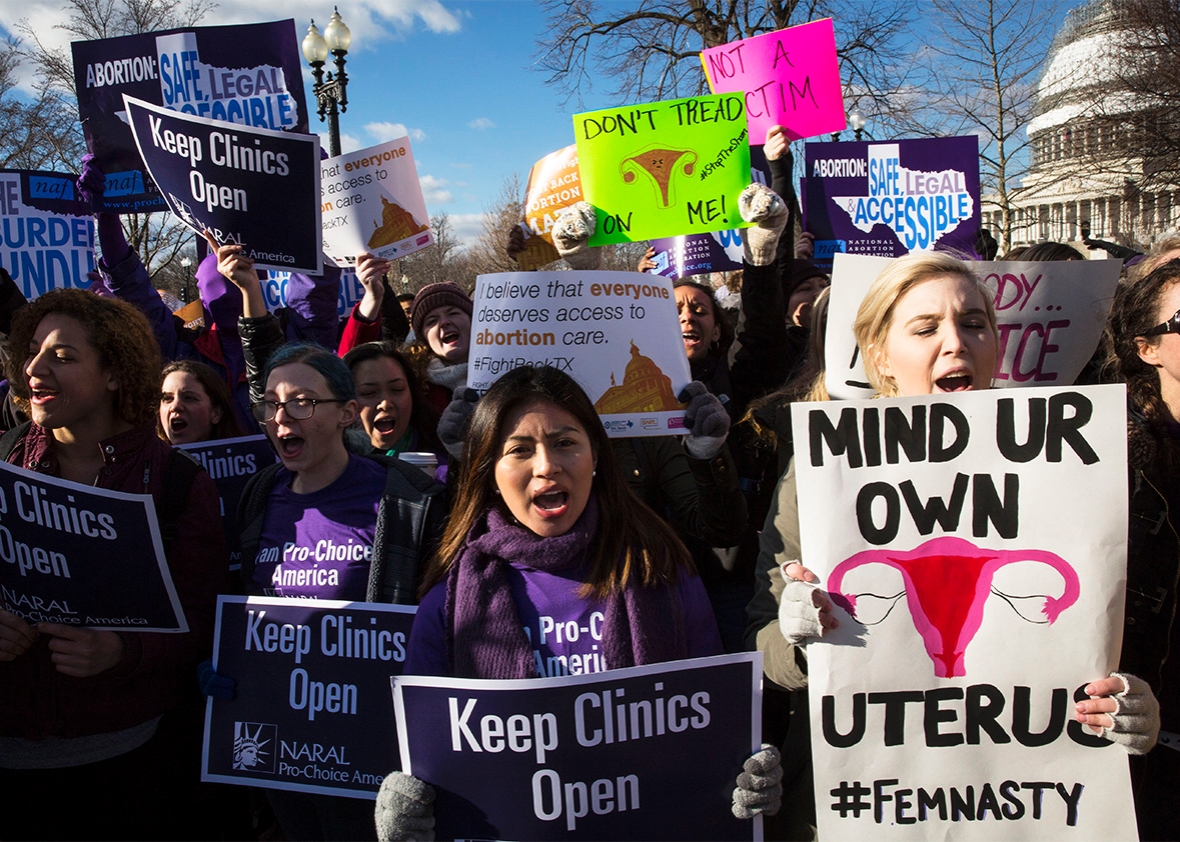

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

We’re posting transcripts of Amicus, our legal affairs podcast, exclusively for Slate Plus members. What follows is the transcript for Episode 39.

In this episode, Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick discusses the case that brought abortion back to the Supreme Court. Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt was argued on Wednesday morning, March 2, making it the first abortion case heard by the high court in nine years. On this episode, Dahlia invites Stanford Law School professor and co-director of the school’s Supreme Court litigation clinic, Pamela Karlan, to help Amicus unpack the case.

To learn more about Amicus, click here.

This is a lightly edited transcript and may differ slightly from the edited podcast.

Dahlia Lithwick: Welcome to Amicus, Slate’s Supreme Court podcast. I am Dahlia Lithwick, Slate Supreme Court reporter. And as you may know already, this was one of those weeks that tend to get us Supreme Court people very, very excited. On today’s show, we’re going to focus on one case, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, that was argued Wednesday morning at the high court as thousands of protestors commandeered the sidewalks outside screaming.

But before we get there, we wanted to bring you a little audio that most of you won’t yet have heard, although news of this sound on Monday morning just about broke the Internet. It all happened early Monday toward the tail end of arguments in Voisine v. United States, a really arcane and frankly boring case about domestic violence convictions and gun ownership.

Ilana Eisenstein: On the face of petitioners hypothetical—

Lithwick: The press gallery was nearly empty. I had only come up to this early case to try to clear my head for the next argument. That was a complicated case about judicial recusal rules. But this argument was proceeding so very snoozily that even the Justice Department lawyer, Ilana H. Eisenstein, started to wrap up her presentation really early. If there are no further questions, she said, signaling her intent to sit down at about 10:45 a.m., 15 minutes before she needed to wrap up.

Eisenstein: If there are no further questions.

Lithwick: And suddenly, heads swiveled, jaws dropped, necks craned, and we all heard something we have not heard in the courtroom in 10 years.

Clarence Thomas: Ms. Eisenstein, one question. Can you give me—this is a misdemeanor violation. It suspends a constitutional right—can you give me another area where a misdemeanor violation suspends a constitutional right?

Lithwick: It was Clarence Thomas. Asking a question. Nobody could believe it. Even the Chief Justice looked stunned. Eisenstein struggled to answer. What? Who’s talking? Thomas pressed on.

Thomas: Well, I’m looking at the—you’re saying that recklessness is sufficient.

Lithwick: Voisine was really just a case about how to read a statute that takes gun ownership away from people who have misdemeanor domestic violence convictions. But Clarence Thomas wanted it to be perfectly clear that this was pushing hard on what he sees as a fundamental Second Amendment right to bear arms.

Thomas: Can you think of another constitutional right that can be suspended based upon a misdemeanor violation?

Lithwick: And so, this colloquy went back and forth, back and forth, with Justice Thomas pressing and pressing on this Second Amendment gun ownership issue, asking at the end nine questions in total.

And finally, it was left up to Justice Stephen Breyer to remind the Court that this is in fact pretty much just a statutory case about how to read the language of a law and that really the big Second Amendment question wasn’t really an issue in the case.

Stephen Breyer: We aren’t facing the Constitutional question. We are simply facing the question of what Congress intended. And if this does raise a Constitutional question, so be it. And then there will, in a future case, come up that question. So, or our point is we don’t have to decide that here.

Eisenstein: That’s correct, your honor.

Breyer: Thank you.

Lithwick: At this point, it’s been less than one month since Justice Scalia left us. But nothing could have made clearer than Monday morning that everything at the court is going to be completely different.

So, now we want to turn to the great, big abortion case that was argued this past week at the Supreme Court.

You’ve probably heard something about Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. This basically was an appeal that came out of HB 2, Texas’ famous omnibus abortion regulation that was passed in 2013 famously over Wendy Davis’ filibuster. Now, there’s only two provisions of the law that are challenged before this particular case in the Supreme Court. One has to do with retrofitting every clinic that provides abortions as an ASC.

That’s ambulatory surgical center. That means things like extra-wide hallways, specific broom closets, and certain air conditioning systems. The other provision has to do with whether doctors who perform abortions need to get what’s called admitting privileges in hospitals 30 miles away from wherever they’re doing the procedure. These kinds of laws are commonly known as targeted regulation of abortion providers, or TRAP laws.

When these two provisions were challenged in the courts in Texas, a district court judge struck them both down saying, nuh uh, these represent what’s called an undue burden on the right to an abortion. The undue burden test, as we’ll discuss later, is the holdover from Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the last time the court heard a big, big abortion case. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said, no, we’re okay with these laws.

They don’t constitute an undue burden. They upheld them. And so, in Texas we’ve seen the state go from 40 abortion providers to 20. And if this law is truly allowed to go into effect, it may be as few as 10 providers left in the entire state where 5.4 million women are of reproductive age. The stakes really couldn’t be higher. We wanted someone really smart and thoughtful on this issue to help walk us through it before we talked about oral argument.

And to do that, we reached out to Pam Karlan, who is calling into the show all the way from Florence, Italy. She teaches law at Stanford Law School and she co-directs the school’s Supreme Court litigation clinic. She served as a deputy assistant attorney general in the civil rights division of the Justice Department. And she is co-author of casebooks, and amicus briefs, and articles, too many to mention. And I should add, Pam, in case you didn’t know this because you’re in Italy, that Cosmopolitan magazine last week named you as one of 13 women who should be considered to replace Justice Scalia.

Welcome to Amicus, Pam.

Pamela Karlan: Thank you so much.

Lithwick: So, let’s talk about the first big, big abortion case that the Supreme Court is considering in nine years. This was going to be a big honking blockbuster, except for the fact that we now have a 4–4 court. Is Hellerstedt still a big deal, Pam?

Karlan: It is still a big deal. And in part, it’s a big deal because the 5th Circuit issues an opinion that essentially allows Texas to close down three-quarters of the abortion clinics in Texas.

And if the Supreme Court divides four to four, that opinion will stay on the books. And thousands—indeed, hundreds of thousands of women in Texas will find it difficult, if they need to get an abortion, to find a clinic in Texas that can perform one.

Lithwick: So, it’s important to flag that even though this may not set any kind of national precedent, it would absolutely have an on the ground impact immediately on coming down.

Karlan: Well, in Texas and in Mississippi, the next state over. And it would set a tone that would give courts around the country faced with abortion restrictions some guidance and some hints as to where the Supreme Court now is on the question.

Lithwick: So, let’s go back to where the Supreme Court was on the question, Pam. I wonder if you could help listeners who aren’t completely sure what happened in Roe v. Wade.

That was an opinion, probably one of the most important opinions authored by Justice Harry Blackman, for whom you clerked. Obviously, this was before you clerked. But can you help us understand the core holding of Roe and what it is that could be on the line this week?

Pamela Karlan: Sure. So, in 1973, the Supreme Court held that the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment, which protects liberty—liberty is the word that the clause uses—encompasses a woman’s decision whether or not to bear a child. That that decision and making that decision is a fundamental liberty that women enjoy. At the time of Roe, the Supreme Court said that in the first trimester of a woman’s pregnancy, she has the right to terminate that pregnancy. And really, the state has very little in the way of regulation that can influence her choice.

In the second trimester, a woman still can terminate a pregnancy that’s still before viability. But the state’s interest has increased somewhat, and the state’s regulation and its power to regulate has increased. And then after viability, states have the power to ban abortion, except in cases where it’s necessary to save a woman’s life.

Now, that was in 1973. The Supreme Court subsequently, in the Planned Parenthood v. Casey case in 1993, changed somewhat the way in which courts analyze restrictions on abortion decisions. And said that a state could not impose what it referred to as an unnecessary burden on a woman’s decision whether to terminate a pregnancy prior to viability.

Lithwick: Now, let’s listen, if we can, to Sandra Day O’Connor reading her opinion in that landmark Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision. This is 1992. She’s reading her opinion from the bench. And let’s listen to how she tried to describe the new test post-Roe.

Sandra Day O’Connor: After considering the constitutional questions decided in Roe, the principles underlying the institutional integrity of this court and the rule of stare decisis, we reaffirm the constitutionally protected liberty of the woman to decide to have an abortion before the fetus attains viability and to obtain it without undue interference from the state.

We also reaffirm the state’s power to restrict abortion after fetal viability, if exceptions are made where the woman’s life or health is in danger. We also hold the state has legitimate interest from the outset of pregnancy in protecting the health of the mother and the life of the fetus that may become a child and that the state may further these interests so long as it does not unduly burden the woman’s right to choose.

Lithwick: So, Pam, help us understand, because this is pretty squishy language, right? What the plurality—and this is comprised, I think surprisingly, of Sandra Day O’Connor, Justice David Souter, and Justice Anthony Kennedy—what they come out with in Planned Parenthood v. Casey is this idea that, sure, the state has an interest in protecting fetal life and protecting the life of the mother. They can throw up some roadblocks, but the roadblocks become impermissible when you reach some magical place called an undue burden.

Is that basically what she’s saying?

Karlan: Yes. And you’ve put your finger on exactly what the key issue is, which is, when does a burden become undue? How do we measure an undue burden versus simply the state’s decision to try and persuade a woman to choose not to terminate pregnancy. And it’s a tough question, and it’s made tougher in the case that the court has in front of it, because there’s a second or a subsidiary question, which is, how do we figure out whether a burden is undue or not?

The 5th Circuit, the court of appeals that upheld Texas’ law said, you don’t look at whether the law actually serves the interest the state says it’s designed to serve. You simply hypothesize about that.

Lithwick: Right. And there’s a real question, looking at this case, whether the 5th Circuit just abdicated its responsibility to—I think as Linda Greenhouse has put it this week in the New York Times—to even look at facts at all.

But I wonder if before we get there, you wouldn’t help us understand the two issues. One of them is the requirement that all abortion facilities become ambulatory surgical centers. The other is the admitting privileges requirement. I mean, both of those sound, I suppose, like they’re not that burdensome on woman and they are protecting women’s health. Can you help us think through what those two requirements are and why they constitute burdens?

Karlan: Sure. I want to stop here for just a moment and say there are two kinds of abortions that are performed early in pregnancy. And we’re talking here about early abortions. There are surgical abortions, which involved dilating the cervix and performing a D&C essentially on a woman, a dilation and curettage, where you remove the contents of the uterus. And then there are so-called medical abortions, which involve pills.

RU-486 is the common way of referring to the drugs that women take that first stop the lining of the uterus from continuing itself, and the result of that is that you can’t maintain a pregnancy. And then a second drug that causes expulsion of the contents of the uterus. So, the first requirement, the ambulatory surgical center requirement says, if you’re going to perform either a surgical abortion or a medical abortion, you have to qualify as an ambulatory surgical center.

Which means, among other things, you have to have a large operating room. You have to have corridors with one-way traffic. Essentially, you have to be a minihospital, as opposed to the kinds of clinics that have been performing abortions in Texas for years and years and years. And for most of the clinics, in order to become ambulatory surgical centers, they’d have to spend more than a million dollars. And many of the clinics actually are on plots of land that aren’t large enough for you to build an ambulatory surgical center.

So, you’d have to go someplace else to build one. So, that’s the first requirement, the ambulatory surgical center requirement. It requires a level of technical equipment and the like that really isn’t used in abortions. It isn’t used at all in medical abortions where people take a pill. And it’s not used in surgical abortions. And to add a kind of insult to the injury there, in Texas, generally when they require that something become an ambulatory surgical center, they grandfather in the facilities that were performing the operation before so that they don’t have to change.

And they have a waiver process, so you can get a waiver from some of the requirement. But HB 2 says that with regard to facilities that perform abortions, you can’t get a waiver. So that, for example, if a woman has a spontaneous miscarriage, her doctor can perform a D&C in a facility that’s not an ambulatory surgical center.

But if she wants an abortion at the same stage of pregnancy, her doctor can’t do that. So, that’s the ambulatory surgical center requirement. The second requirement is a requirement that a physician who performs an abortion have admitting privileges at a hospital within thirty miles of the site where he performs the abortion. So, within 30 miles of the clinic. And here’s the difficulty with that.

Many hospitals don’t give admitting privileges to doctors whose practices don’t generate large numbers of admissions to a hospital. So for example, in the record in the Texas case, there’s one hospital that says if a physician doesn’t perform or expect to perform 24 procedures at the hospital in the course of a year, they’re not going to give them admitting privileges. Because admitting privileges are really about the business of a hospital. Well, here’s the problem with that.

Abortions in Texas are so safe that no doctor who performs abortions is going to necessarily have 24 admissions to a hospital in a year. That would be a sign of a terrible doctor in a practice that involves performing abortions.

Lithwick: Is it worth saying also, Pam, that part of the reason we don’t really need admitting privileges is that hospitals have to take, no matter who you are, if there’s some crisis, a hospital has to take you. And also, that a lot of hospitals are declining to give admitting privileges to physicians for all sorts of religious and political reasons, right?

Karlan: Absolutely. Your doctor’s admitting privileges simply go to whether your doctor, in some sense, will take care of you in the hospital, not to whether the hospital will take care of you. And as several of the amicus briefs point out, not only does a hospital have to take you if you have a health emergency, but in many cases they expect that a doctor within the hospital or a hospitalist from your primary care physician’s office is going to be the person overseeing your hospital care, not the doctor who performed a discreet procedure like an abortion.

Lithwick: So, this raises this fundamental difficulty at the center of this case, which is that the pretext that all of the TRAP laws are done under this guise of: Look, we’re just helping women, we want things to be safe.

But then we know one fact in this case is that Texas’ lieutenant governor, David Dewhurst tweeted—when HB passed—a map of Texas showing all of the clinics that would be closed. He tweeted that this would essentially ban abortion statewide.

So, part of what’s really odd about these TRAP laws is that it’s pretty understood that the point is to shutter clinics. That’s the point. And yet, undergirding all of this is this language of helping women be really safe from a procedure that is in fact far safer than a colonoscopy or other surgical procedures that aren’t regulated this way.

Karlan: Well, in Texas, it’s actually 100 times safer to have an abortion than to carry a pregnancy to term. The death rate for abortions in Texas is .27 women per 100,000 procedures performed. And the death rate among women who carry a pregnancy to term, the mortality rate is 27 per 100,000.

So, everybody understands that this is not really about a woman’s health. But the Supreme Court created this temptation to make arguments about women’s welfare in the Gonzales v. Carhart decision, which talked about the interests of the woman. And so, you know, the anti-abortion folks, the anti-choice folks have realized that arguments that pit a woman’s interest against a fetus’ interest tend not to persuade the people they’re trying to persuade.

And so, they are trying instead to argue that they’re really trying to help women, because that’s a way to try and blunt what would otherwise be the obvious response to them, that they’re trying to deny women the right to choose.

Lithwick: And just to be clear, Carhart is the 2007 case in which the court chose to uphold the partial-birth abortion ban. So, this brings us inexorably, as every show brings us inexorably to Anthony Kennedy.

Karlan: For now.

Lithwick: For now. Because he was in this plurality in Casey. And it’s worth pointing out, since Casey, he has upheld every abortion restriction that has come across his desk. He is not ambivalent about this. But can I ask you what your thoughts are on really the raft of fascinating amicus brief in this case that are the narrative briefs?

I think Adam Liptak had a story about how Amy Brenneman is involved in an amicus brief, the actress. And that there’s been a real attempt to humanize this fact that, you know, 1 in 3 women has had an abortion in her lifetime. These are real people, that their own autonomy and economic necessity required this. Do you think there are similar briefs on the other side saying that?

Karlan: Yeah, the regrets brief.

Lithwick: The regrets brief.

Karlan: Yeah.

Lithwick: And I wonder, it seems to me as though this is an attempt to put a face on Hellerstedt. But I wonder if you think it’s a sort of an attempt to say to Justice Kennedy, look at these people. These are real people. This is not just a question about the Constitution. These are real women, and these are their lives.

Karlan: Well, I think it’s certainly an attempt to do that. Whether it will have an effect one way or the other is hard to know. I think some of the inspiration for these briefs, I think it’s kind of twofold. One is to combat his reliance, Justice Kennedy’s reliance in Gonzales against Carhart, on a regrets brief, by saying, we’re women who have abortions and we don’t regret it. It was the right decision for us. So that he understands that this is at best a mixed issue.

The second thing is, I think it reflects a broader understanding of the movement that led up from Bowers v. Hardwick to Obergefell.

Lithwick: Now, Pam, let me be clear. Bowers v. Hardwick is the 1986 case that upheld the constitutionality of Georgia’s sodomy laws that would criminalize sex between private, consenting adults if they are gay.

Karlan: Sure. So, in 1986, which was actually the high-water mark of abortion rights at the Supreme Court, the year of Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which reaffirmed Roe and struck down a number of provisions that actually were quite like the provisions that the Supreme Court later upheld in Casey. That was the low-water mark for gay rights in the United States. It was the year of Bowers v.Hardwick and an announcement by five members of the Supreme Court that they thought any claim by gay people to the liberties that everyone else enjoyed was—and here I’m quoting the Supreme Court—“at best facetious.”

Well, fast-forward to 2013 and the Windsor case and 2015 and the Obergefell case. What changed during that time? Well, what changed is gay people came out. And I think that affected how judges thought about the claims of gay people to equal rights. Because it wasn’t just that they knew gay people. They now knew that they knew gay people.

And over that same period of time, abortion became increasingly a private concern in some ways. And so, of course the justices all know people who’ve had abortions. But they may not know that those people have had abortions. And I think some of the impulse in these briefs is to do for reproductive rights and reproductive autonomy what the coming out movement did for the LGBT community.

Lithwick: So, Pam, of course the response to that on the other side is Kermit Gosnell, Kermit Gosnell, Kermit Gosnell. And for listeners who aren’t aware of who he is, he was the former Philadelphia abortion doctor who was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for abortion procedures that were not only illegal but quite horrific and graphic.

And so, what we hear often in the briefs on the other side and proponents of these Texas regulations is, look, we are just trying to protect against the fact that abortion doctors are corrupt and abortion facilities are filthy abortion mills. And this is a story that I think leads us to, you know, David Daleiden and the Planned Parenthood sting videos. And just the version of the story that is, that everything about Planned Parenthood, about Whole Woman’s Health, about you know, women’s reproductive care is basically corrupt and filthy and needs to be hyper-regulated.

Karlan: Well, you know, abortion, like all other medical procedures, was already regulated. And nothing about the Texas law is going to make abortion safer in Texas. And they already had the power to go after abortion providers who didn’t maintain safe and sanitary facilities. That’s not anything that this law provided that wasn’t already there.

Lithwick: So, is the reliance on horror stories about Kermit Gosnell, the abortionist who really did commit horrific atrocities, is that just for lack of any other argument? That it’s such an important sort of placeholder in the briefs on the other side?

Karlan: I think that’s right. I mean, I don’t think that pointing to one doctor who violated a series of laws in another state is a justification for shutting down a series of clinics that had lower mortality rates than even the low mortality rates of abortion providers in other states. This law was totally unnecessary to protect women’s health. And the only real effect of this law was to do what its proponents intended, which was to shut down abortion clinics willy-nilly.

Lithwick: I wonder if you can just end by coming back to something you said at the very beginning of this conversation, which is that the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, when they had the opportunity to look at HB 2 and to look at the district court order below which had struck down both of these laws, simply said, you know what? Ours is not to decide facts. And this is the quote from the 5th Circuit opinion. “It is not the Court’s duty to second guess the legislative fact-finding, improve on, or cleanse the legislative process.”

So, basically, I think what they’re saying is, we’re giving carte blanche to legislatures to just make some argument that sounds pretty plausible and we’re good. That’s a complete abdication of the judicial role, isn’t it?

Karlan: Well, it’s not just a complete abdication of the judicial role. But it really flies in the face of what the plurality opinion, the joint opinion, said in Casey, which is you have to look at what the purpose and the effect of a law are. And if the purpose of the law is to put a burden in the way of women who want to make the decision that is constitutionally theirs to make, the law is invalid.

So, you have to look at the purpose of the law. You can’t just say, well, here’s a purpose that might be okay. You have to ask what the actual purpose of the law was.

Lithwick: So, we want to thank you, Pam Karlan, for calling in from Florence, and to set you free back to enjoy art and good food until you return to the United States.

Karlan: Oh, there’s good food in the United States.

Lithwick: Pam Karlan teaches law at Stanford Law School where she also co-directs the school’s Supreme Court litigation clinic. And Pam, we so enjoyed having you on the show today, and hope to have you back soon.

Karlan: I hope so too. Ciao.

Lithwick: Now we want to take you inside the top-secret, red-curtained courtroom for the actual oral arguments in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. Now, the audio is already up over at the U.S. Supreme Court website.

And I would really urge you to listen to all 90 minutes of it when you’re at the gym, because it is awesome. But we wanted to put some of it into your ears before we let you go this weekend, because it was, to be sure, a barnstormer. So, to set the scene, I want to start with Stephanie Toti, who represents to abortion clinics that are challenging these new Texas regulations. Here is here opening statement.

Stephanie Toti: Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the court, the Texas requirements undermine the careful balance struck in Casey between state’s legitimate interests in regulating abortion and women’s fundamental liberty to make personal decisions about their pregnancies. They are unnecessary health regulations that create substantial obstacles to abortion access.

Lithwick: Eventually, the chief justice, John Roberts, begins to closely question Toti about whether the 10 or 11 clinics that have had to close in Texas did so specifically because of the new law or they did so for some other reason and what that other reason might be.

Toti: —the timing of the closures alone—

John Roberts: I’m sorry. What is the evidence in the record that the closures are related to the legislation?

Toti: The timing is part of the evidence, your honor.

Lithwick: After a little while, Justice Elena Kagan jumped in to supply the answer to that question.

Elena Kagan: Ms. Toti, could I just make sure I understand it? Because you said 11 were closed that the admitting privileges requirement took effect. Is that correct?

Toti: That’s correct.

Kagan: And is it right that in the two-week period that the ASC requirement was in effect that over a dozen facilities shut their doors? And then when that was stayed, when that was lifted, they reopened again immediately? Is that right?

Toti: That is correct, your honor.

Kagan: It’s almost like a perfect controlled experiment, as to the effect of the law, isn’t it? It’s like, you put the law into effect, 12 clinics closed. You take the law out of effect, they reopen.

Lithwick: Now, around now is where Justice Anthony Kennedy—remember, his first name is All Eyes on Kennedy—suggests that maybe the solution is to just remand this whole thing back to the lower courts in Texas and have them take another look.

Anthony Kennedy: The state, I think, is going to talk about the capacity of the remaining clinics. Would it be, A, proper, and B, helpful for this court to remand for further findings on clinic capacity?

Toti: I don’t think that’s necessary, your honor. I think there’s sufficient evidence.

Lithwick: At this point, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg hops in to ask the chief justice to give the lawyer for the clinics a little bit more time. Here she is.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: We have absorbed so much of your time with the threshold question. Perhaps, can she have some time to address the merits?

Roberts: Why don’t you take an extra five minutes, and we’ll be sure to afford you rebuttal time after that.

Toti: Thank you, Mr. Chief Justice.

Lithwick: With this extra time, Justice Sonia Sotomayor decides it’s time to argue her case. Let’s have a listen.

Sonia Sotomayor: There’s two types of early abortions at play here. The medical abortion, that doesn’t involve any hospital procedure. A doctor prescribes two pills, and the women take the pills at home, correct?

Toti: Under Texas law, she must take them at the facility. But that is otherwise correct.

Sotomayor: I’m sorry. She has to come back two separate days to take them?

Toti: That’s correct. Yes.

Sotomayor: Alright. So, now from when she could take it at home, it’s now she has to travel 200 miles or pay for a hotel to get those two days of treatment.

Toti: That’s correct, your honor.

Lithwick: Long after Stephanie Toti’s time is up in defending the clinics, Justice Sotomayor is still going. And she’s showing no sign of letting up. Here is her closing back and forth with Stephanie Toti.

Sotomayor: So, your point I’m taking is that the two main health reasons show that this law was targeted at abortion only.

Toti: That’s absolutely correct. Yes, your honor.

Sotomayor: Is there any other—

Roberts: Thank you, counsel.

Sotomayor: I’m sorry. Is there any other medical condition, like taking the pills, that are required to be done in hospital? Not as a prelude to a procedure in hospital, but an independent. I know there are cancer treatments by pills now. How many of those are required to be done in front of a doctor?

Toti: None, your honor. There are no other medication requirements and no other outpatient procedures that are required by law to be performed in an ASC.

Roberts: Thank you, counsel.

Lithwick: Now it’s Don Verrilli’s turn. He’s the United States solicitor general. And he’s been given 10 minutes to argue against the Texas restrictions on behalf of the Barack Obama administration. Justice Samuel Alito continues to press him hard on whether there is any good evidence that the remaining clinics in Texas, there will only be nine left when this law goes into full effect, can’t just take care of all of the state’s needs.

Samuel Alito: There’s no evidence of the actual capacity of these clinics. And why was that not put in? If we look at the Louisiana case, we can see that it is very possible to put it in. And some of the numbers there are quite amazing. There’s one doctor there who performed ,3000 abortions in a year. So, we don’t really know what the capacity of these ASC clinics are.

Don Verrilli: Well, I think you have expert testimony in that regard.

Alito: Yeah, but what is it based on? It’s not based on any hard statistics.

Verrilli: Well, it is. It’s common sense that you can’t—

Alito: Well, common sense, no.

Verrilli: But beyond that, as I said, Justice Alito, they studied the period of time in which half the clinics in the state were closed. And you would expect that those clinics, that if the additional ASCs can handle the capacity, they would have. And they didn’t.

Lithwick: Now it’s the Texas Solicitor General, Scott Keller’s, turn at the podium. He’s been given 30 minutes to defend this Texas statute, but Ruth Bader Ginsburg kind of comes at him like the Tasmanian devil.

Ginsburg: How many women are located over 100 miles from the nearest clinic?

Scott Keller: Justice Ginsburg, JA-242 provides that 25 percent of Texas women of reproductive age are not within 100 miles of an ASC. But that would not include McAllen, that got as-applied relief. And it would not include El Paso, where the Santa Teresa New Mexico facility is.

Ginsburg: Yeah, that’s odd that you pointed to the New Mexico facility. New Mexico doesn’t have surgical ASC requirement, and it doesn’t have any admitting requirement. So, if your argument is right, then New Mexico is not an available way out for Texas, because Texas says, to protect our women, we need these things.

Lithwick: And then it’s Justice Sotomayor tagging in again.

Sotomayor: According to you, the slightest health improvement is enough to impose of hundreds of thousands of women, even assuming I accept your argument, which I don’t necessarily, because it’s being challenged. But the slightest benefit is enough to burden the lives of a million women. That’s your point?

Keller: And what Casey is the substantial obstacle test examines access to abortion.

Lithwick: And a few minutes later, there’s Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, all 90 pounds of her, back in the ring and she is punching double-time.

Ginsburg: I can’t imagine what is the benefit of having a woman take those pills in an ambulatory surgical center when there is no surgery involved.

Lithwick: Justice Anthony Kennedy comes back into the argument because he actually wants to talk about the health effects of the Texas law.

Kennedy: But I thought an underlying theme, or at least an underlying factual demonstration, is that this law has really increased the number of surgical procedures as opposed to medical procedures. And that this may not be medically wise.

Lithwick: And a few minutes later, it’s Justice Stephen Breyer’s turn to take a whack at Scott Keller in probably one of the funniest moments of the case.

Breyer: Where in the record will I find evidence of women who had complications who could not get to a hospital even though there was a working arrangement for admission, but now they could get to a hospital because the doctor himself has to have admitting privileges?

Which were the women? On what page does it tell me their names, what the complications were, and why that happened?

Keller: Justice Breyer, that is not in the record.

Breyer: Fine. So, Judge Posner then seems to be correct when he says he could find in the entire nation, in his opinion, only one arguable example of such a thing, and he’s not certain that even that one is correct. So, what is the benefit to the woman of a procedure that is going to cure a problem of which there is not one single instance in the nation? Though perhaps there is one, but not in Texas.

Lithwick: And here’s Ruth Bader Ginsburg again.

Ginsburg: As compared to childbirth, childbirth is a much riskier procedure, is it not?

Keller: Well, the American Center for Law and Justice and former abortion providers’ amicus briefs dispute that.

Ginsburg: Is there really any dispute that childbirth is a much riskier procedure than an early-stage abortion?

Lithwick: Then it’s Elena Kagan’s turn to ask Scott Keller why it is that Texas feels it needs to regulate abortion for a woman’s health sake when colonoscopies and liposuction have much, much higher complication rates.

Kagan: I guess I just want to know, why would Texas do that?

Lithwick: Justice Samuel Alito steps in to help Keller along a little.

Alito: But as to rogue facilities, which Justice Kagan just mentioned. One of the amicus briefs cites instance after instance where Whole Woman’s facilities have been cited for really appalling violations when they were inspected. Holes in the floor where rats could come in. The lack of any equipment to adequately sterilize instruments. Is that not the case?

Lithwick: Toward the very end of the argument, Ruth Bader Ginsburg starts to press Keller on whether we shouldn’t really worry most about the women, the poor, the rural, the minority woman, who will be hardest hit by clinic closures. Keller tells her, this isn’t about regulating women’s rights to abortion. It’s just about regulating doctors and clinics.

Keller: When a law is regulating women, as it would in a spousal notification provision, that might be different. But when we’re talking about doctor and clinic regulations, when the law is going to have a relevant effect is going to be for every doctor and every clinic. Which is precisely why the 5th Circuit noted that that was proper the denominator, all women in Texas of reproductive age.

Lithwick: But Ruth Bader Ginsburg is having absolutely none of that.

Ginsburg: What it’s about is that a woman has a fundamental right to make this choice for herself. That’s the starting premise. Casey made that plain, that the focus is on the woman, and it has to be on the segment of women who are affected.

Lithwick: All of which goes to show that you can put an old veteran ACLU, women’s rights warrior into a lacy collar, but every once in a while, at least on Ginsburg, it looks like she’s wearing a pair of golden gloves.

And that is going to do it for another episode of Amicus. As always, we are eager to hear whatever thoughts you have about this week’s show. You can share them with us at amicus@slate.com. We love your letters. Thank you. We also love reading the reviews of Amicus on our iTunes page. And they’re a great way to help other people find out about our show. So, if you haven’t already left one of your own, there’s no time like the present.

Search Amicus in the iTunes store and click on the ratings and reviews tab. Remember that if you’ve missed any of our past shows, you can always find them at slate.com/amicus. And we also post transcripts there, but you do have to be a Slate Plus member to access them. You can sign up for a free trial membership to Slate Plus at slate.com/amicusplus. And when you do, know that transcripts take a few days to post. This week’s excerpts from the Supreme Court’s public sessions were provided by Oyez, a free law project at the Chicago Kent College of Law, part of the Illinois Institute of Technology.

You can find it at oyez.org. Thank you as always to the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, where our show is taped. Our producer is Tony Field, Steve Lickteig is our executive producer, and Andy Bowers is the chief content officer of Panoply. Amicus is part of the Panoply Network. Check out our entire roster of podcasts at itunes.com/panoply.

I’m Dahlia Lithwick. We will be back with you soon for another edition of Amicus.