Exonerate Cameron Todd Willingham

The family of a man executed on faulty arson evidence pushes for reform.

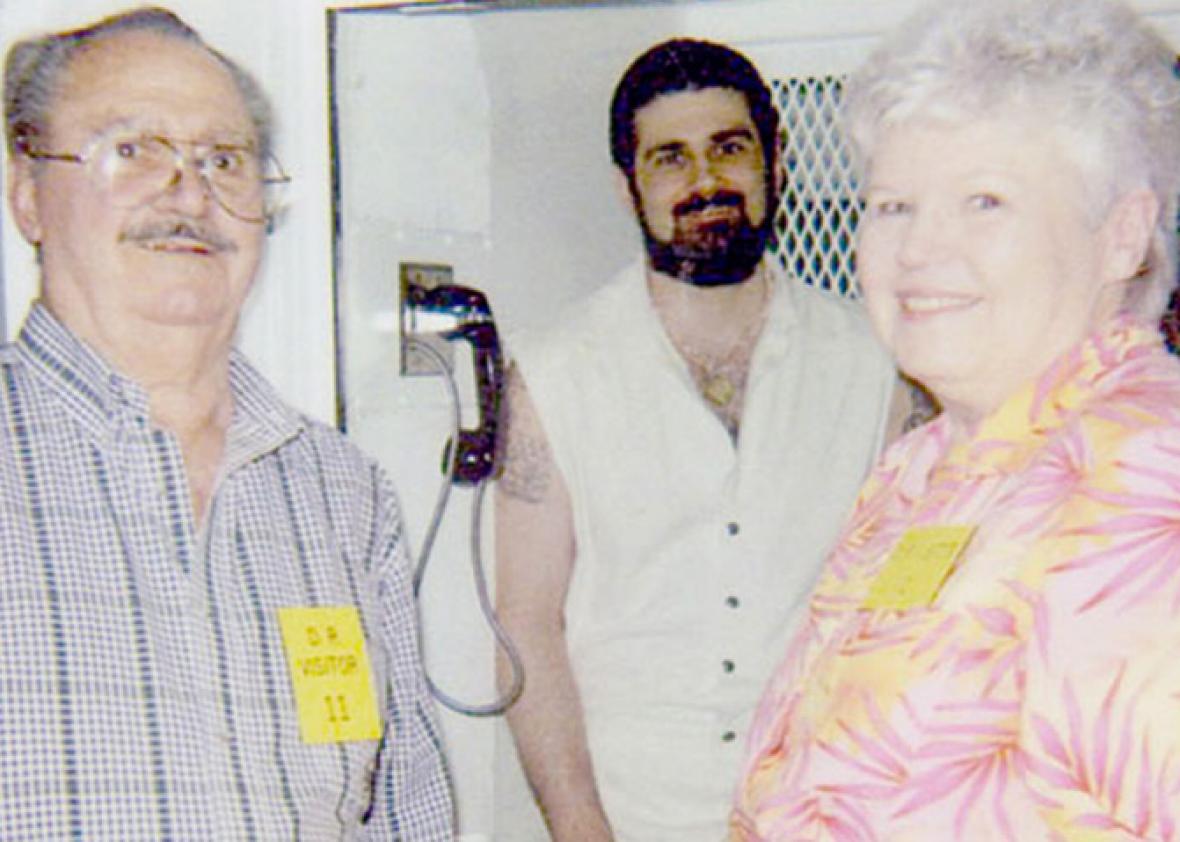

Photo courtesy of Cameron Todd Willingham’s family.

This story is part of a special Slate Plus package on Jeremy Stahl’s “The Trials of Ed Graf.” Be sure to check out another Slate Plus exclusive related to this story, a look at how Texas executed Cameron Todd Willingham based on junk science and then tried to cover it up.

Cameron Todd Willingham was in jail, charged with murdering his daughters, when he supposedly confessed to a fellow inmate named Johnny Webb. Based in part on Webb’s testimony, Willingham was convicted, sentenced to death, and executed in 2004 despite overwhelming evidence, which was clear at the time of his execution, that he was an innocent man.

Navarro County District Attorney John H. Jackson called the supposed confession the second pillar of his prosecution. The first pillar was forensic evidence that Willingham had intentionally set his house on fire and left his children to suffocate and burn. That evidence has been discredited. Last August, the second pillar came undone as well when the snitch recanted and claimed that Jackson paid him off for his testimony and then lied to the jury about it. (Jackson, who has described the charges that he paid off Webb as a “complete fabrication,” did not respond to multiple messages requesting comment left with his law office.)

The steps that Jackson allegedly took to ensure Webb’s testimony and continued cooperation, as documented by the Marshall Project and the Washington Post, are terrifying. Webb now says one benefit he got was having a first-degree robbery charge (with a deadly weapon) knocked down to a robbery two (without a deadly weapon). An unsigned note in the prosecutor’s files seemed to confirm this claim. It said that Webb’s first-degree robbery conviction would be downgraded to second degree “based on coop in Willingham.”

“That’s evidence in writing that there was a quid quo pro,” the co-director of the Innocence Project Barry Scheck told me.

These sorts of deals are supposed to be disclosed to defense attorneys. Instead, the prosecutor emphasized to Willingham’s jury multiple times that Webb had gotten no deal whatsoever.

Another unsigned note to the county clerk’s office said that “per John Jackson,” Webb’s charge had been downgraded. After Webb threatened to recant in 2000, Jackson wrote directly to him to say that he was meeting with a wealthy rancher regularly on Webb’s behalf and that he had worked “to get you released early in the robbery case.” Over the years, Webb received thousands of dollars in support from that rancher. Webb did end up briefly recanting in 2000, but his letter was sent to Jackson and never placed in Willingham’s case files or shared with his appellate attorneys.

“He recanted before Todd was executed. And they stuck it in a drawer,” Willingham’s stepmother Eugenia Willingham told me.

Webb’s testimony about Willingham’s supposed confession was coerced by Jackson, Webb now says. “[Todd] never told me nothing,” he told the Post.

The Innocence Project has since filed a grievance with the Texas State Bar charging Jackson with prosecutorial misconduct. The state bar agreed that there was evidence of misconduct and will hold a hearing that could result in Jackson’s disbarment. Scheck says that even without a quid pro quo, for which there is evidence, the act of downgrading Webb’s sentence after he had pleaded guilty to a first-degree robbery was “illegal.”

The upshot of all this is that now none of the evidence used to execute Willingham can be believed.

Gov. Rick Perry refused to offer Willingham a posthumous pardon as he left office. That’s understandable considering he’s the one who put him to death. Perry has an obvious political, and presumably psychological, investment in Willingham’s guilt. But Scheck believes that one day soon the state of Texas will officially recognize Willingham’s innocence. “I think that over the next few years there will be a governor of Texas that will pardon Cameron Todd Willingham,” Scheck told me last year. “I’m sure of it.”

Willingham’s execution brought attention to the shoddy state of arson science in the state. Despite extensive resistance from Texas politicians, the state established an agency to review past arson investigations. The arson reviews would not have existed without Cameron Todd Willingham, and his family has taken some pride and comfort in that fact. “That makes me feel good,” Eugenia said when I described to her the reforms being enacted because of her stepson’s death.

“That’s the one thing that gives Eugenia and I the most comfort, I think,” Todd’s cousin and staunchest advocate Pat Cox said. “Because if nothing happens, from right now on, if nothing else ever happens, [if] we actually don’t get his name completely cleared, then we have already won.”

Eugenia, Pat, and Pat’s sister Judy Cox spoke with me over the course of several hours at Eugenia’s family home in Ardmore, Oklahoma, at the end of 2013. Eugenia greeted me wearing a giant sparkling cross around her neck and with homemade chocolate cake ready to share. Her home is decorated in a Coca-Cola theme—Coke dishes, Coke glasses, a Coke clock. As we thumbed through old photo albums and prison letters, she would occasionally become quiet and seem to go elsewhere.

“This was one of his posters when he lived at home,” Eugenia told me, pointing to a photo of a teenage-looking Todd standing in front of a heavy metal poster with a devil character rising out of flames.

“Led Zeppelin,” chimes in Pat. “They’re a hard rock group. And of course you know everyone that listens to Led Zeppelin is a devil worshiper!”

At trial, this argument was actually made in earnest by a psychological expert and goose-hunting partner of the prosecutor named Tim Gregory. “There’s an association many times with cultive-type of activities,” Gregory said, describing Willingham’s rock posters. “A focus on death, dying. Many times individuals that have a lot of this type of art have interest in satanic-type activities.”

All three women have a sharp sense of humor, which is the only way I can imagine enduring the ordeal the family has lived through and remaining sane. Since Todd’s death, Eugenia, Pat, and Judy have been tireless advocates for his exoneration, taking on the Texas legal system. All three are warm, generous, and collected when talking about the tragedy that befell their family. The most emotional Eugenia got was when she tried to read one of Todd’s letters from death row. At one point she wondered aloud if she’d be able to finish reading, and at others she teared up.

“I never did anything worth a damn to speak until my daughters were brought to my arms,” Eugenia read her son’s words, her voice cracking. “I could not protect my own extensions of life from harm. That makes me a failure.”

Eugenia Willingham reading a letter written by her stepson, Cameron Todd Willingham, who was executed based on faulty forensics. The letter was written from prison. This interview was recorded by Jeremy Stahl.

The letter is a devastating meditation on the guilt Todd said he bore for being unable to save his daughters from the fire.

“He’s really quite eloquent with his writing,” Pat said.

“He told me he had changed a lot in prison,” Eugenia added.

The family remembers when Todd learned that the jailhouse snitch Webb was going to testify. Eugenia advised her stepson that all he could do was talk to his lawyer, David Martin. His defense attorney’s response, according to Eugenia: “That’s just another nail in your coffin.” Martin never believed Willingham’s innocence and still didn’t even after the new forensic science evidence came out—going on national television in “informal cow-checking attire” to personally attack the scientists who had debunked the arson myths used against his former client. So certain was Martin of Willingham’s guilt at the time of the trial that he pushed Willingham’s parents to try to convince him to take a plea deal.

“They offered him life, but he was going to have to admit guilt, and he said, ‘No way,’ ” Eugenia recalled. “I just cried. I begged him to take life because I didn’t want him to go to death row … because I knew they were going to kill him.”

Ed Graf’s attorney Walter Reaves made a last-minute appeal on Willingham’s behalf, arguing that research from arson scientist Gerald Hurst showed the evidence used to convict him did not hold up to scientific scrutiny. Gov. Perry refused to stay the execution.

Eugenia and the Cox sisters were with Todd right before he died and remember it vividly. They also have mementos of that day. In the photo album there’s a shot of Todd grinning with his hands clasped in his prison whites dated Feb. 17, 2004, with a timestamp of 11 a.m. He was executed at 6 p.m.

“He said ‘Momma, they’re gonna execute me. I don’t care what you say who said what,’ ” Eugenia recalled.

“He had come to terms with the fact that he was going to die,” Pat said.

“He said ‘I’m a lucky man, I got to say all my goodbyes,’ ” Judy added.

Judy, particularly, remembers the details of that day. She and her cousin Todd looked alike, with jet-black hair and “a certain Indian look”—Judy says the family is part Chickasaw—and Todd joked with Judy, “Do you think our good looks got us in trouble?” After saying their goodbyes, the family sat and waited for word that the execution had gone through.

“The clock … there was a clock in the hospitality room. And it started chiming. And we were to stand up and hold hands—the chaplain wanted us to hold hands—and that clock was right to my left, and I could hear that chiming [snaps fingers in time with clock], as it chimed off. And I was counting them, because they were going to execute him at 6. And I’m thinking to myself, This is something out of a really, really bad movie.”

A prison official entered, handed Eugenia a black trash bag tied in a knot, and told them, “These are all Todd’s belongings, and if you want to see him, he’s still warm.”

“I mean it was like business as usual. No problem,” Judy recalled. “ ‘Run down there, touch him, feel him, look at him, because we’ve done our job.’ ”

Judy described the experience as life-changing. “This was an abomination to me personally and a wake-up call,” she said. “If you actually think it’s gonna be okay and that justice does prevail, you are seriously kidding yourself.”

Looking at how the state fabricated its case against Willingham, it’s hard not to become disillusioned. And yet, even these three women, who have seen firsthand the justice system’s worst abuses, still favor the death penalty and offered a lengthy, heartfelt defense of it. They believe it’s the justice system that’s broken, not the institution of the death penalty, and that it was a just penalty for certain people that were guilty “beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

“It’s not the death penalty itself. It’s that process by which we deem a man to be guilty or innocent and that process by which we convict,” Pat Cox said. “It’s the process leading up to the death penalty.”

“I had talked to Todd about that. And he says, ‘There’s people in here, Mama, that need to be executed,’ ” Eugenia Willingham remembered. “He said, ‘They are definitely monsters.’ ”

According to the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center, Texas alone executed 70 people between 2010 and 2014, three times as many as the next nearest state. This is actually a steep decline from the number of people the state was executing last decade, when it carried out 248 executions. That number peaked in 2000 with 40 people put to death by the state in George W. Bush’s final year in the governor’s mansion.

All that’s left now for the Coxes and Eugenia to do is keep petitioning the parole board and the governor every two years to try to get a pardon. The irony is, Eugenia noted, that Todd died not knowing the extent to which the science and the recantation of Webb would exonerate him.

“He went to his grave not knowing the truth,” said Barry Scheck. “He certainly knew he was innocent.”

It seems almost inescapable that he did know that.

“Well, that’s a lot to know,” Scheck concluded.

Read these related articles about arson investigations in Texas: