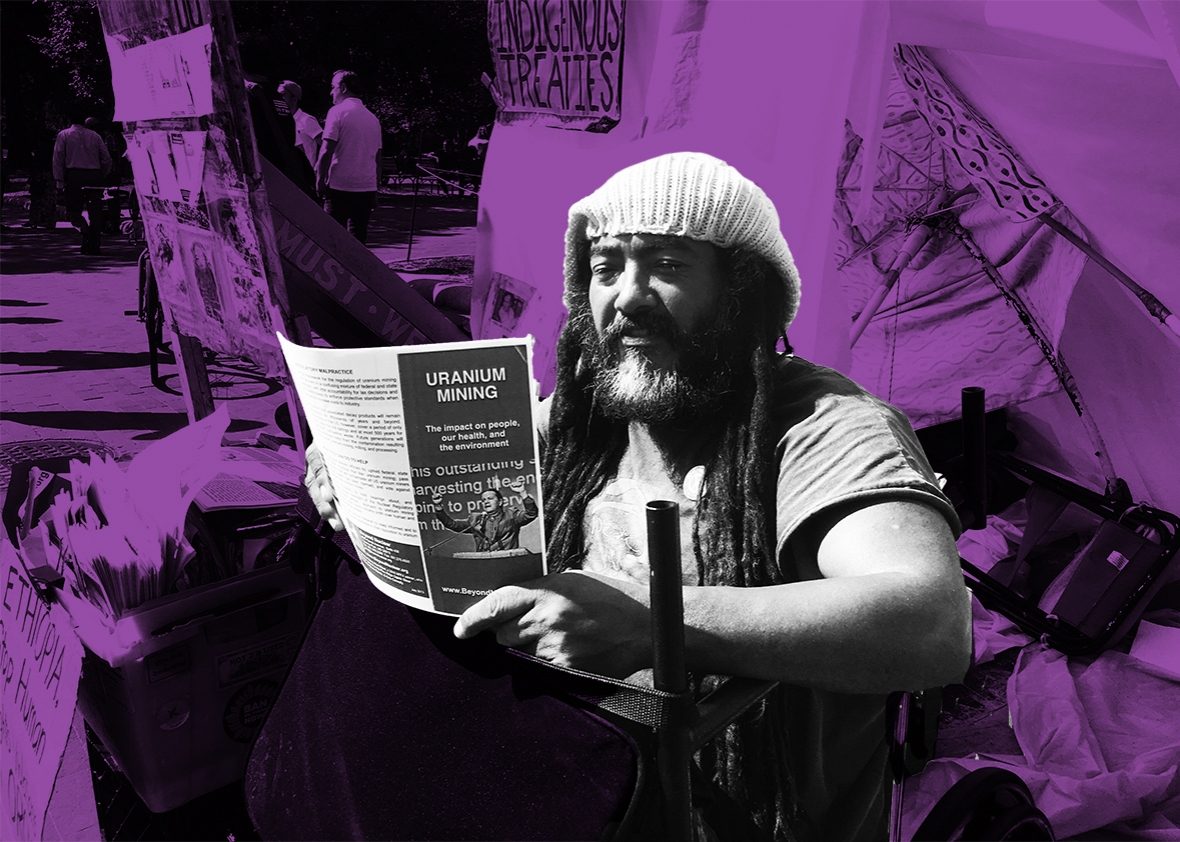

This Man’s Been Protesting Outside the White House for More Than 30 Years

Slate’s Working podcast talks to protester Philipos Melaku-Bello about his anti–nuclear war vigil.

Photo illustration by Slate. Image by Mickey Capper

On the most recent episode of Working, Slate’s Jacob Brogan talks to Philipos Melaku-Bello, the protester who has spent more than 30 years maintaining an anti–nuclear war vigil outside the White House. Through blizzards, hurricanes, and scorching heat, Melaku-Bello has talked to tourists, politicians, D.C. residents, and just about everyone in between about his message of world peace. Melaku-Bello is just one of the regular volunteers at the vigil and is largely responsible for managing daily operations.

In this episode, Melaku-Bello talks about the lesser-known parts of public protesting, such as what regulations affect the vigil and its volunteers, as well as what it takes to work days as long as 17 hours in inclement weather.

And in this episode’s Slate Plus bonus segment, Melaku-Bello talks with Brogan about the history of the vigil, starting with its founder, William Thomas Hallenback. How does Hallenback’s legacy continue to inspire him, as well as the other volunteers? And how have things changed over the years as a protester?

Jacob Brogan: You’re listening to Working, the podcast where we talk to people about what they do all day. I’m Jacob Brogan. Like Washington, D.C., itself, the White House plays host to a transitory population of staffers. In the area just outside its fence perimeter however, a more permanent crew of protesters has been operating for more than 30 years. We spoke to one of them this week, Philipos Melaku-Bello, an anti-nuclear activist who mans the William Thomas Memorial Peace Vigil in beating snow and piercing rain alike.

We sat with him in the partial shade of the vigil’s rag tag tent surrounded by the clamor of the protesters, tourists, and the passing occasional Secret Service officer. It was a noisy place. You’ll hear people chattering, performers prancing, and much more, but we thought it was important. It’s in that environment Melaku-Bello has to convey his own message, and it’s in that environment that he’s been working for decades. Melaku-Bello discussed the shape of his days which often stretch to 17 hours, and the supplies that he brings with him.

In the process he told us about his interactions with passersby, the support network that keeps him going, and how he interacts with the world around him. On that there’s maybe the most surprising detail of all—his friendship with the squirrels of Lafayette Square. And in a Plus Extra, as Melaku-Bello tells us, about the more than 30-year history of the vigil he now operates. If you’re a member, enjoy bonus segments, and interview transcripts from working, plus other great podcast exclusives, start your free two-week trial today at Slate.com/workingplus.

What is your name and what do you do?

Philipos Melaku-Bello: My name is Philipos Melaku-Bello. I am here across the street from the White House. It’s the William Thomas Memorial Peace Vigil, and I protest for world peace against nuclear and atomic weapons, and against human rights violations.

Brogan: How long have you been out here?

Melaku-Bello: I started helping out in 1981. I didn’t become very regular until about ’84.

Brogan: So what inspired you to start back then?

Melaku-Bello: No, the inspiration didn’t start when I first came here. I was already by 1984 organizing protests against the Vietnam War and against nuclear and atomic weapons in Southern California. So me and my brothers, we were already organizing protests because we saw our father do it. So the inspiration probably comes from my father, was a long time activist. That was actually in front of the White House in ’52 and ’53, protesting against the Korean War and atomic weapons as nuclear hadn’t been fully developed yet.

Brogan: So you’re part of a long family tradition of protesting in front of the White House where we are right now?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah, yeah, it’s kind of like I’m a legacy guy, like if you go to Harvard, and your uncle went to Harvard, you’re probably going to get in there.

Brogan: So you stay here now overnight outside of the White House?

Melaku-Bello: Actually we had a volunteer, Concepcion Picciotto who passed away Jan. 25 of this year, but I was doing nearly every other night, but there have been volunteers who have come forward since she passed away, offering to help me out, so now I’m doing only one overnight a week, so that’s great, going from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Brogan: Can you tell us a little bit about this space you all have built up here itself?

Melaku-Bello: By regulations the sign can only be 4 feet by 4 feet, so I can have two of them flanking this area here, that is a makeshift tent, we’ll call it.

Brogan: Is there a reason it has to be makeshift?

Melaku-Bello: Yes, it’s in regulations. In my other bag I have the 28 pages of regulations with an average of three to four regulations on each page. It’s 91 total regulations on the vigil, so it looks like there’s not even enough out here that they can possibly make 91 regulations.

Brogan: So you’ve got the signs, the makeshift shelter tent area. Do people sleep in there, in that tent space?

Melaku-Bello: By law they’re not supposed to sleep. Nobody’s ever here the hours I’m here, so if they do a six or seven hours overnight—

Brogan: So when they’re doing an overnight that just means they’re sort of sitting out over the course of the night?

Melaku-Bello: By law.

Brogan: Yeah, in theory, by law.

Melaku-Bello: Yeah, I better not wink.

Brogan: Sure.

Melaku-Bello: I better just verbalize it. [laughs]

Brogan: For the record you did not wink. So what kind of stuff are you spotlighting on the signs themselves?

Melaku-Bello: Until William passed away, I had a lot of information on the nuclear and atomic industry, and sometimes I would read him articles on the nuclear and atomic industry, and he’d either use them or would use some of the quotes and make a good sign out of those.

Brogan: So what’s your day to day like? When do you come out here in the morning?

Melaku-Bello: Saturday and Sunday morning I come out, Saturday at 5:30 a.m. and Sunday about 7:30 a.m., and both of those days I stay until either 10:30, 11:15.

Brogan: More than a full-time job.

Melaku-Bello: Oh yeah, 17 hours Saturday, 16 hours Sunday, and an average of 11 to 13 hours Monday through Friday—Thursday.

Brogan: You’re seated for most of that time?

Melaku-Bello: I’m in a wheelchair, so yeah, I’m seated.

Brogan: What are the most rewarding encounters in the course of the day? You talk to a lot of people? Do you interact with the tourists going by?

Melaku-Bello: I love them. I love them. I mean I love people I’ll never meet. This is a protest for world peace.

Probably like 6.9 billion people that I’ll never meet that it’s my love letter to the planet. I mean it’s not only for the people because obviously if the planet Earth, if it was engaged in an nuclear holocaust it would take the animals and plant species with it, so it’s really a love letter to the planet. That’s what it is when you protest for peace.

Some people will come here and they’ll yell at me that I hate the United States. Well, if I’m protesting for world peace, I don’t know which world the United States is in. It’s not saying I want world peace exclusively of the United States. I’m not saying that.

Brogan: You are here across the street, literally across the street from the columns of the White House itself. Do you see yourself as trying to address the President, trying to address people who are in this position of power?

Melaku-Bello: The beauty of the White House is that it’s part of D.C. that people come and they visit their consulate and their embassy, and while they’re in D.C., we might as well visit the White House, and they do.

Brogan: So when you position yourself here then, for 17, maybe more hours a day, it’s partially to address the tourists from all over the world that come to this spot?

Melaku-Bello: Right. It’s more an international feeling. In front of Congress there’s way less international community and with it closing at 5 to 9in the morning, there would be a lot of void time, but we’re still, according to what we’re doing, would have to maintain a presence for 24 hours a day.

Here, I’d say through 11, there’s at least a dozen, two dozen people you can talk to, and then again from 2:30 until about 4 you have the midnight stumblers, the last-call revelers. So then you have a little bit of a crowd again. It’s just like an hour and a half in between, then by 5:30 people are walking on the way to work.

Brogan: How do you relate to the people going by?

Melaku-Bello: I never talk to the people until they get on the sidewalk, or if they’re definitely looking at me and trying to get my attention, because this is what I believe in and it’s why I don’t use bull horns.

I believe people have the right to visit the White House and not have to hear me from 250 feet away.

Brogan: So I’m just a person who walks up to your booth, is looking at your signs, is reading them, but isn’t saying anything to you. Do you start talking to me or do you just wait for me to talk to you?

Melaku-Bello: If they look at my signs I’ll greet them.

Brogan: What do you say to them?

Melaku-Bello: Hello. How are you? Hola, como estas?

Brogan: Try any other languages?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah, yeah, aloha, [speaking other languages]. I will speak until I get a giggle, then I know which one, sometimes even in languages I can’t carry conversations in.

Brogan: How many languages can you carry conversations in?

Melaku-Bello: Eight.

Brogan: Wow.

Melaku-Bello: I’m multilingual.

Brogan: That’s amazing.

Melaku-Bello: But I mean, I know several hundred Hebrew words and several hundred Arabic words.

Brogan: When you start talking with them, whatever the language, what do you talk about? Do you usually broach the question of nuclear war?

Melaku-Bello: I go straight into what we’re here about, the nuclear war industry, world peace, the human rights violations that have been identified by the United Nations, and knowing that that’s only what they’ve identified.

Brogan: How long does the usual interaction with someone last?

Melaku-Bello: I have students that have kept coming for an hour and a half once a week for seven or eight years.

Brogan: Is that how you think of students, the term used to describe the people who come to the—

Melaku-Bello: I mean they started as high school students and then they stayed in the area, and went to American, TW, Howard University, Georgetown.

Brogan: What about just the typical tourists? How long do you spend talking to them?

Melaku-Bello: I think average is 15 minutes.

Brogan: I notice you have next to you at your right is a big bin of papers. Is that literature you hand out?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah, on the nuclear industry, on the depleted uranium, Eleanor Holmes Norton. She’s the representative in Congress that can’t vote, as we know.

Taxation without representation in Washington, D.C. The whole reason the United States fought England was because of taxation without representation, and it is alive and well in the nation’s capital.

Brogan: So you have a wide range of topics that you can cover with people, not just nuclear war but also taxation without representation here in the District.

Melaku-Bello: Everything that fits within political science. That’s why I keep having these students who come back. It’s usually like they’re in a class, political science class.

Brogan: Do you ever interact with people from the White House itself?

Melaku-Bello: I won’t speak on record on that one.

Brogan: So today, the day we’re talking to you, it’s brutally sunny. The sun is starting to go down right now. Yesterday we were going to talk to you and unfortunately it was raining, but you or someone connected with the vigil is out here all the time, every day, right?

Melaku-Bello: Right.

Brogan: How do you deal with extreme weather? You’re under an umbrella right now, but is that enough?

Melaku-Bello: I don’t know. I mean not this last winter but two winters before that we broke the all time cold two consecutive years in Washington, D.C., for any winter.

So negative 14-degree days, with the windchill factor was a negative 28, had 85 mile an hour winds, so it was deemed a hurricane.

Brogan: And you were out here in that?

Melaku-Bello: Oh yeah.

Brogan: You’re like the Postal Service.

Melaku-Bello: I’m here hurricane, blizzard, tornado.

Brogan: Why is it important to you to be out here when there’s no one for you to speak to?

Melaku-Bello: Because then this will be taken away. That’s the way it can be taken away, abandonment.

Brogan: Someone has to be here at all times?

Melaku-Bello: They’re waiting. They’re waiting for it to be abandoned by way of snowfall, blizzard, hurricane.

Brogan: So you have other volunteers who help maintain the vigil, right?

Melaku-Bello: Right. Josh Casey, he helps me out for four overnights a week, and then there’s Craig Thompson that helps me out two nights a week, and three mornings, and there’s a man named Neil that helps me out three mornings, and one overnight.

Brogan: How do you coordinate those volunteers?

Melaku-Bello: I’ve been the coordinator of the volunteers for ages.

Brogan: Do you keep a schedule or something? Is there an email list, a Google document?

Melaku-Bello: No.

Brogan: You don’t do it electronically? It’s all in your head?

Melaku-Bello: No. See, a lot of things that we do, we still do it the way William and I did it. If I have a 40-person roster, I’d use a computer.

Brogan: If you want to touch base with someone do you call them on the phone? How do you get in touch?

Melaku-Bello: I’ve got a cellphone.

Brogan: Yeah. So you just give them a ring? That must have gotten helpful, that change, because you didn’t have that when you started.

Melaku-Bello: No, even by ’91, ’94, a cellphone was still the size of two bricks.

Brogan: There’s a woman over here blowing what looks like a shellfire. Is she a regular out here? Is that someone that you know?

Melaku-Bello: I’ve seen her about seven times in the last 25 years.

Brogan: Seven times in the last 25 years?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah.

Brogan: That’s a deep memory.

Melaku-Bello: Yeah.

Brogan: So there are people who come through not just regularly but occasionally?

Melaku-Bello: I mean, she has come out with fliers that had George Herbert Bush’s face on it and it said, “This is the face of the devil.”

Then about 15 years later she had a flier and the face on the flier was George W. Bush, so I’m going to assume, and I don’t think it’s a crazy assumption, she was perfectly OK with Bill Clinton. And then since Barrack Obama’s been in office I hadn’t seen her much, then it was about 10 weeks ago she came out with a flier and the only thing that was changed is Donald Trump’s face was on there.

Brogan: Let’s talk about the volunteers again. What if someone has to move a shift or something like this? You just handle that by phone, make calls to the other people and see if they can come in?

Melaku-Bello: No, I just cover it.

Brogan: Cover it yourself?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah.

Brogan: So you’re out here even more sometimes than 17 hours a day?

Melaku-Bello: I mean, I’ve been here 96 hours through blizzards. I mean whatever it takes.

Brogan: When that happens someone brings you food I hope.

Melaku-Bello: No. You see, blizzards and hurricanes, you can track those, so I bring food, and with Igloos, you can lock the container so vermin can’t get in.

So yeah, for those times I’ll bring food, but on a regular we don’t store food in the vigil.

Brogan: So you don’t have to truck this stuff in here every day. How much stuff do you bring when you come out here? What do you bring with you when you arrive?

Melaku-Bello: A satchel with the fliers I’ve made for that day, or a specific thing that popped up on the news. I might want to emphasize what’s happening on the news and bring some literature about that.

Brogan: Where do you print that stuff out?

Melaku-Bello: Gonzo style. There’s people in small municipality government that—

Brogan: That help you out?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah, because there’s people in government that they have causes they care about.

Brogan: It seems like it would be expensive to support this. How does this work out financially?

Melaku-Bello: The amount of money I make through the spring and summer is enough for the fliers to continue probably through December, so January, February, March, and April, I go in the hole, inside of my pocket.

Then it never catches up, then each year it’s out of my pocket in those months.

Brogan: Why is it easier in those months?

Melaku-Bello: There’s more trips out here.

Brogan: So you’re mostly supported by donations, by people who just give when they swing by?

Melaku-Bello: Yes, that’s what supports me.

Brogan: Just people dropping money in the—

Melaku-Bello: In the bucket.

Brogan: Can I ask how much it usually brings in?

Melaku-Bello: According to the time of the year, but April, May, early June, $45, and remember, I have volunteers that need their transportation costs to get here, and go home, including me. So you’re still not making much.

I mean maybe if everyone got a coffee, their transportation costs, then July, August, early September, that’s when I’m making enough money to keep the fliers and transportation surviving through the end of December. Then we go back to that time where I go in the red anywhere from some years $1,200 to $2,600 a year that it’s my money making sure that people have the money to get here and volunteer to do this.

Brogan: So it’s that money you have from when you used to work before doing this?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah.

Brogan: Saved up?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah.

Brogan: Sounds like you have to live pretty frugally to do this?

Melaku-Bello: Completely, completely. I don’t take vacations. What I wear was either given to me or I went to a thrift store. Even thrift store prices are too much, only when I know a thrift store is having a sale. I haven’t had a brand new pair of shoes that I bought for myself in 25 years.

Brogan: What size are you?

Melaku-Bello: Some shoes 9½, some shoes 9s.

Brogan: Do people ever try to give you things?

Melaku-Bello: Oh yeah.

Brogan: Donations besides money?

Melaku-Bello: In January before the blizzard started, there were two young men that came through that had come from the green party, from Ralph Nader’s office in Washington, D.C., bought me boots, scarves, a sleeping bag, two blankets, hand warmers, and foot warmers, a 12-pack of socks, and 12-pack of underwear, and that’s from Ralph Nader’s office, Green Party.

Brogan: How important are those kinds of donations to sustaining your ability to keep working here?

Melaku-Bello: It’s more like it makes you feel that someone’s listening beyond the point of, hey, that’s a photo opportunity. Look at that. That’s across the street from the White House. Looks like he wants the downfall of the U.S. government. Let’s go take a picture of that. That might be a little something rare. You know?

Brogan: What are the most important parts of running the stand? Transportation? Is that the main expense?

Melaku-Bello: Fortunately petrol cars are down to about two and a quarter, but when it was up at four and a quarter, almost twice as expensive, that was tough, and then occasionally nothing else will come through, or buses aren’t allowed to run. So I had a friend that made it a couple of times right after the blizzards were over, but still the streets hadn’t been fully cleaned, and he used Uber that time.

Another one came through and used a taxi, and ran down here to see if I made anything during a blizzard, and I just looked at him and go, what did you think I made during a blizzard? Do you think people are out here in 85 mile an hour torrential snowfall? I mean there’s nothing in the bucket.

Brogan: It’s been here for 28 years, 27 years?

Melaku-Bello: No, 1981, 35.

Brogan: 35, wow.

Melaku-Bello: That’s the human sacrifice I’m willing to make of my life for the humans of this planet. I’m out here as a human sacrifice to bring down the damage if I can possibly, even more, on nuclear threat.

Brogan: We’ll just wait until this group passes. You’ve been listening to White House protester Philipos Melaku-Bello. After these people clapping and dancing in the background move on we’ll talk to him about why he sticks with it and why he remains hopeful.

Are there elements of this area we’re in, across the street from the White House that you like? Trees, or lights, or bits of grass? Is there anything about this area that you’ve found that you really have especially taken to that you love?

Melaku-Bello: The squirrels.

Brogan: You love the squirrels?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah, because the squirrels, they come to us knowing if we brought nuts …

Brogan: The squirrels come to you?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah, little treats with peanut butter in it, or something that they—even grains, or people give me oats for me to make my breakfast at home with it, but I see the squirrels come up and I’m going to feed them oats.

Brogan: Do you get to know particular squirrels?

Melaku-Bello: I have names for them.

Brogan: How do you recognize them?

Melaku-Bello: I know their markings. If you see squirrels for every day of their life until they have—because squirrels don’t have very long lives, but you know them.

Brogan: Are they friendly?

Melaku-Bello: They’ll come on my lap.

Brogan: Wow. Does that happen often?

Melaku-Bello: The colder it gets, I think they like being around contact. So during those months when I said there’s less people, and maybe I’m going into my own pocket to run the vigil, then I have squirrels, and they’ll be on my lap, and sometimes they’ll climb up my wheelchair and sit right there on my shoulder.

The people that do come up, they’re like freaked out, like this doesn’t happen in nature. But if I’m a guy that doesn’t want the planet Earth to go through a nuclear holocaust, I’m doing as much for the animal life, the wildlife, as I am for humans, because once this is gone it’s gone for all the things in nature. I mean, I don’t see that much there that is going to survive 1,000 278-degree nuclear blasts.

Brogan: Do you ever get bored out here? How do you deal with that?

Melaku-Bello: I trigger things in my mind that I’ve been doing since I was a little kid?

Brogan: Like what?

Melaku-Bello: I’m in a happy place. I’m in a warm place. I do what I used to call telepathic transportation where I transport myself to Kenya, or Ethiopia, or Brazil, because it’s so damn cold. Boredom, I’m all the sudden at a Beatles concert, or Grateful Dead concert, and Bob Marley and the Wailers, or name it.

Brogan: Do you read?

Melaku-Bello: Miles Davis. I read a lot. During those winter months I will bring a lot of reading, but during—like right now it’s raised up the amount of people out here because it’s after work hours, so if there’s 50 people around me I’m not going to break into a book and two paragraphs my attention is on them and getting the message out.

Brogan: What kinds of stuff do you read?

Melaku-Bello: I read books in eight different languages, everything from Charles Bukowski, William S. Hunter, Hunter S. Thompson, Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Saul Alinsky, any of the books that were written by the members of the Weather Underground.

Brogan: What about the Secret Service that controls this area of Pennsylvania that we’re in outside of the White House? Do you ever have any hassles with them? Do they ever bug you?

Melaku-Bello: Secret Service, they’re lovely chaps.

Brogan: Do you know those guys by name?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah.

Brogan: You interact with them much?

Melaku-Bello: I’m not going to say any of their names.

Brogan: Sure, that’s fine. But they know you?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah. I mean, when it’s really cold coffee can come my way by way of the Secret Service, a muffin a bagel. If it’s very extremely hot—I mean it’s not all the time, but water, iced tea will come this way, and sometimes by hand of Secret Service, but more often it’s by the hands of the lovely people that come by and think that this protest is needed, and that it’s in the right place.

Brogan: Do you keep a lot of supplies in the tent yourself of food, water, stuff like that, to sustain you throughout the day?

Melaku-Bello: No. Food becomes rat food. I have probably a little more than a case of water in there and a two and a half gallon container of water, so water we need, yes, of course, but besides that there might be some backup paperwork, bug repellent. During the summer it can have mosquitoes.

Brogan: Do you wear sunscreen ever?

Melaku-Bello: No.

Brogan: Just get tan out here?

Melaku-Bello: I mean, I’m under this too. So I’m not getting a tan. I’m under the umbrella.

Brogan: What else do you have to have that gets you through the day every day?

Melaku-Bello: Love.

Brogan: Love?

Melaku-Bello: Love.

Brogan: Just from the people walking by or your love for the world?

Melaku-Bello: Both. It’s an equal exchange.

Brogan: Sometimes the Secret Service does have to clear this strip of Pennsylvania Avenue when the motorcades are going through. Do you stay here when that’s going on or do you have to move?

Melaku-Bello: There’s times they’ve let me stay and there’s times—three of my friends that I would consider my best friends amongst the Secret Service, they’ll say something like, eminent, or say a word like possible danger. We’ve got to call in. And those are trigger words because now only about—I think about 15 or so weeks ago, there was a situation where Vice President Biden, he was still in the Eisenhower Executive Building and there was a shooting around the corner, and it ended up being deemed that it was suicide by cop, that that guy, that was the way he wanted to go out, I guess like a martyr.

Brogan: Did you have to move when that happened?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah. At that time one of the Secret Service agents came by and let me know, “Philipos, it’s eminent.”

Brogan: It seems like you have a lot of stuff here. Are you able to move all of that when something like that happens?

Melaku-Bello: No, we don’t have to move the things.

Brogan: You just leave temporarily and come back?

Melaku-Bello: Just roll out with my wheelchair, take maybe one sign, take the bucket, get some of the folded makeshift brochures and go up to Eighth Street.

Brogan: Will you be here during the inauguration next year?

Melaku-Bello: They move us, but they can’t move us out of the park. They setup the bleachers here for the inauguration.

Each inauguration they move us into the park, but they can’t move us from the park.

Brogan: So you just move the whole vigil?

Melaku-Bello: The signs and everything.

Brogan: Do you talk to other protesters out here? Clearly you’re not the only group protesting out here. Is there a community of protesters?

Melaku-Bello: I’ll say this: During the spring and the summer they have a few of them that do the weekdays, but of course heavier on the week, but once that college vacation is gone, you only see it on the weekend. I mean there’s artistic expression out here, but they’re not protesters.

Brogan: This guy across the street from us?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah.

Brogan: Painted all in silver.

Melaku-Bello: And then there’s people using their freedom of religion rights, handing out the tracts for the Jehovah’s Witnesses, but Monday through Friday when the college students go back, it can be pretty lonely for protesters out here, but the activists that come through, most of them know who I am.

Brogan: Is the advice you give to people who are protesting out here?

Melaku-Bello: I mean there was ones that were going to travel out to Ferguson and before they traveled out to Ferguson, quite a few D.C., Maryland protesters came through and asked me for advice.

Brogan: What advice do you give to protesters? What’s your most—

Melaku-Bello: What I try to tell them is you have the right to a peaceful protest. That’s part of the First Amendment to the Constitution. You don’t have the right to a violent protest. Now it’s up to you where you want to take it. If you’re willing to get violent, which I don’t advocate, because I protest for world peace, I’m not going to judge you, but you might have to face a judge, and I’m not talking about after this life.

I’m talking about you might have to physically face a judge because you’ve chosen to get violent. I’ll tell them this too. Stick to what the protest is about.

Brogan: Important to know your target. You said you keep all the rules for protesting here in your bag by your side. Does that help you stay focused to attend to what the official policies and rules are, that keep you away from a judge?

Melaku-Bello: Yes, and then also if other people are going to protest anywhere throughout the District of Columbia, like I said, people come to me for advice.

So I not only have the advice. I have paperwork from the Department of the Interior.

Brogan: You know the rules for the whole area.

Melaku-Bello: Yes, and then other activists have been surprised when they’ve seen people from the Department of Justice, Department of the Interior, Department of Defense, Secret Service park police, park rangers, come and embrace me, because it’s, “Well, they’re protesters.” That seems like that’s the other side. No.

I mean sometimes I can ask them for assistance or clarification of a law and I need to be humane with them.

Brogan: So you’ve been involved with this vigil throughout I think five presidential administrations? Regan, Bush, Clinton, Bush, Obama.

Melaku-Bello: Right.

Brogan: Have things changed? Has your experience of being here changed over the course of different presidential administrations?

Melaku-Bello: Oh yeah. I mean Bill Clinton disarming 10,287 nuclear warheads, the planet Earth disarming 10,695 nuclear warheads, but not one before this protest started.

Brogan: But what about the tone of life out here? Has that changed? Have the kind of people that come by, the way the people talk to you, the way the people listen or don’t, has that changed?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah, the Regan administration, during that time, and then you know, it was right backed up by George Herbert Walker Bush, so there were 12 years there where people willing to physically put their fists on our face, and jaw, and head, and smack us, has changed, except for the last two years that the vigil was stabbed at, sharp rocks were thrown through, and it was completely torn apart.

Brogan: When the vigil has been attacked, torn apart, otherwise damaged, are you able to rebuild it? Is that ever an issue in terms of the obligation to keep it able to stay operating?

Melaku-Bello: The last time I just went right to my cellphone, and I got on Facebook, and I put the word out, and 40 minutes later one person was here, and an hour and a half later, six people were here, and three hours later there was 12 people here who had brought more of the building plastic, brought duct tape, clamps, Gorilla Glue.

Brogan: When something like that happens, do you file a police report?

Melaku-Bello: No.

Brogan: Why not?

Melaku-Bello: I’m an anarchist, and I don’t want anyone to lose a minute of freedom for their lapse of judgment or their lifelong brainwash by their government.

Brogan: Has there ever been a time where you just wanted to give up and stop? Have you ever thought about quitting?

Melaku-Bello: No, because the face of a little girl in Bangladesh, or a little boy in Cambodia, and the thought of a nuclear blast going off close enough to them for them to lose their life, is enough. Again, this is a love letter. This is a love letter to all the civilians of the planet.

Brogan: How would you know when your work here was done?

Melaku-Bello: When we get to global zero on the nuclear, meaning power plants and weapons.

Brogan: So total nuclear—

Melaku-Bello: Disarmament.

Brogan: At all levels.

Melaku-Bello: At all levels.

Brogan: Do you expect that will happen in your lifetime?

Melaku-Bello: If it doesn’t, I don’t care if I don’t see the day. If I spark the mind of the person that sees it done, I’ll be happy.

Brogan: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us.

Melaku-Bello: You’re welcome.

Brogan: Thanks for listening to this episode of Working. I’m Jacob Brogan. We’d love to hear your thoughts about the podcast. Our email address is working@slate.com. We do read all of those messages and we try to reply to them. You can listen to all seven seasons at Slate.com/working. This series was produced by me and Mickey Capper.

Mickey also edits the show. Thanks to Hakim Shapiro. Our executive producer is Steve Lickteig, and the chief content officer of Panoply is Andy Bowers.

* * *

In this Slate Plus extra, Philipos Melaku-Bello tells us about the more than 30-year history of the vigil that he now operates. Can you tell us a little bit more about the history of the vigil itself?

Melaku-Bello: William Thomas Hallenback, he started the vigil. He was the one that was here first. He was an activist, a hippy.

He was born in New England area and spent early life in New York as well, then in the 1960s was in New Mexico.

Brogan: Do you know what inspired him to start this particular vigil?

Melaku-Bello: He had been a hippy, and at first he wanted to protest for world peace because it was the right thing to do, world peace dude, some very hippy thoughts, which I loved the guy. I’m not making fun of him, but very simplistic.

And he had this part about he was always seeking wisdom and honesty, and he wanted to see if he was able to survive without having anything to do with going out there and seeking finance. But if enough came for coffee, or somebody brought him a coffee, or a sandwich, twice in a day, he wanted to see if it could be done. He also had gone across Africa, through the Middle East, Europe, a total of 31 countries, including Puerto Rico.

He had already been to Canada and had already been to Mexico, living here in North America.

Brogan: Once he started the actual vigil, were there ever times when it was seriously in jeopardy, when it seemed like it might get shut down, or have to end?

Melaku-Bello: I mean I was here only three weeks later on one of the tours with one of my bands, which was a political band. My father already knew of him and knew him, so I came and checked on my father’s friend, then when I saw him I knew him too from when he’d be around my dad when I was a little kid.

I came and I helped him in the D.C. area, on the East Coast, for about 10 days and five shows, I came and helped him, even seven days because when I played in Maryland and played in Virginia, you don’t go to sound check until later on, so I had daytime to come and visit him too. Then I did that again in late ’81, ’82, ’83, so like I said before, from ’81 to ’84, I helped when I could.

Brogan: After this vigil had been going on for a while, eventually Concepcion Picciotto was the person who was probably most identified with it for most of its history. What was she like?

Melaku-Bello: I love the true story of Concepcion, because the true story of Concepcion shows that she was a woman that was not going to let down her efforts to try to have visitation rights with her daughter, so she couldn’t have possibly been here when this was founded, because she was doing good things in New York, trying to keep things in the courts.

But eventually she lost the right to visitation without court authorized adult supervision, and she didn’t believe that she should ever be supervised to see her daughter. She adopted her daughter.

Brogan: So she was not involved with this place heavily until she was no longer able to spend time with her daughter, is that what you’re saying?

Melaku-Bello: Right.

Brogan: What was Concepcion’s personality like? What drove her?

Melaku-Bello: She was in love with William Thomas, and love is a great thing. I’m never going to say anything bad about love. William Thomas considered her his best female friend, but like platonic female friend. So what drove her is the pros— when she wanted to have a platform to stand on, she was able to speak loudly on that platform as well.

Brogan: So was she more aggressive about reaching out to people walking past than you are?

Melaku-Bello: Yeah. She put her hands on people. I won’t.

Brogan: So the kind of tenor of the tone, of the vigil, has really changed depending on who’s operating it?

Melaku-Bello: What has happened is it’s gone back to—many people come through here and say, “When I come through here, it’s like I’m talking to William again.”

William trained me a lot. Then my father who was protesting two and a half decades before William, I mean, I’m his kids.

Brogan: What did you learn most from William during your time with him here?

Melaku-Bello: He was the person that was compassionate, and he came from a place where he had seen a lot of the world, and myself too, having worked for the King of Ethiopia. We had those things that were in common, so we could understand each other very much.

There’s nothing wrong with only having been to three, four, seven countries, but it’s not the same as him being the 31 countries and me being in 91 countries.

Brogan: How did things change here when Concepcion died earlier this year?

Melaku-Bello: More people were willing to come and help.

Brogan: Because less aggression?

Melaku-Bello: Right. I mean, I was getting congratulated by people because it looked like I was returning it to the way William had it, but there was also people that were coming out and saying that they were giving me their condolences.

Those are the ones that said, “We will always respect a person that stood up for what she believed in, even if we didn’t always agree with what she was saying. The length of time that she stood up for what she believed in was amazing.” I say that too. I mean 32 years helping do this is amazing.