The Evolution of Everyday Objects

How smart design makes good things great.

Read all the stories in Slate’s new series on the evolution of everyday design. And don’t forget to nominate everyday objects you’d like us to cover at everydayobject@gmail.com.

-

Composite created from Key from 14-15th Medieval Key from The Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum; typical modern key from Getty Images/iStockphoto; hotel keycard from The Time.

Composite created from Key from 14-15th Medieval Key from The Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum; typical modern key from Getty Images/iStockphoto; hotel keycard from The Time.The Key

As you read this sentence, you almost certainly have a small, grooved slab of metal somewhere on your person. You used it to lock your front door this morning. You’ll use it to get back into your place tonight. In between you might use it to open a box or a bottle of beer, but these are unauthorized applications. I’m talking, of course, about your house key, which probably looks a lot like my house key. It’s also not so different, in its essential function, from the keys that ancient Romans used, thousands of years ago, to lock up their precious items: It’s a metal form that—when inserted into an opening and turned—draws back a bolt or latch. But the metal key is marked for extinction. Electronic access controls—keycards, keypads, biometric scanners, and the like—are already common in hotels, office buildings, and cars, and they’re gaining ground. What will we lose when the metal key, a form that has endured for centuries, disappears? And what will we gain?

-

Photograph by Stan Sherer/Project by Mara Bishop, '00, and Amanda Payne Burton, '97, Smith College History of Science, Museum of Ancient Inventions

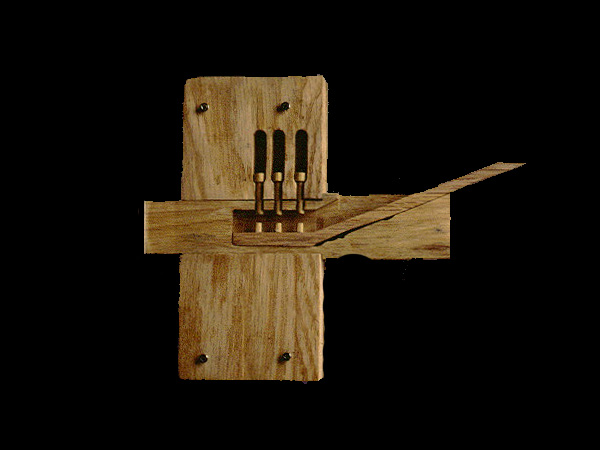

Photograph by Stan Sherer/Project by Mara Bishop, '00, and Amanda Payne Burton, '97, Smith College History of Science, Museum of Ancient InventionsModel of Ancient Assyrian Lock

To understand the history of the key, you must understand the evolution of the lock. One of the most sophisticated locks used in the ancient world was found in 1842 at Khorsabad—in what’s now Iraq—at the palace of the Assyrian king Sargon II, who ruled just before 700 B.C. As the reproduction at left shows, the door opener would use a large, pronged wooden key to lift a series of movable pin tumblers into a position that allowed the wooden bolt to slide open. Although the key shown here looks unfamiliar—more like a rake or a comb than what we’re used to—the locking mechanism is stunningly similar to the ones we use today, most of which also rely on sliding tumblers into place. Although this relatively secure mechanism soon spread from Assyria to Egypt and across the ancient world, it eventually fell out of favor in the West, and wasn’t revived until the 1800s.

-

Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum/Smithsonian Libraries.

Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum/Smithsonian Libraries.Roman Keys

Most ancient Roman locks were less sophisticated. The locks these bronze keys operated would have used simple lever mechanisms to draw back the bolt. Note that each of the keys at left features a hole so it can be worn on a strap or chain, the Roman equivalent of a keyring. (The Romans weren’t big on pockets.)

-

Waterton Collection/Victoria and Albert Museum.

Waterton Collection/Victoria and Albert Museum.Roman Key

In Ancient Rome, having keys—or anything worth locking up—was uncommon. So the key was as much a status symbol as a security device. Affluent Romans often kept their valuables in secure boxes within their households, and wore the keys as rings on their fingers. The practice had two benefits: It kept the key handy at all times, while signaling that the wearer was wealthy and important enough to have money and jewelry worth securing.

-

Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum/Smithsonian Libraries.

Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum/Smithsonian Libraries.Medieval European Key

During the next 1,500 years or so in Europe, the ornamentation of keys evolved, but the locking mechanism didn’t change much. In the medieval period, keys were more commonly made of iron than bronze, but they retained both their practical and symbolic purposes: securing valuables and showing that you were important enough to have valuables to secure. One way to convey your significance in this period? By carrying a really big key, like this one, which measures 31 centimeters long.

-

Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum/Smithsonian Libraries.

Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum/Smithsonian Libraries.Medieval European Keys

Some useful key terminology: The bow is the part you hold onto while turning it; the bit is the pronged part that enters and activates the lock, and the shaft connects the two. During the 14th and 15th centuries, from which these keys date, the bits feature ornamental as well as functional detail.

-

Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution.Medieval European Key

A few centuries later, in the 1500s and 1600s, the bows of keys were more ornamented than the bits—often featuring finely wrought tracery that resembled the ornate windows in Gothic cathedrals.

-

La Fidele Ouverture/CREDIT: blacksmithebooks.com

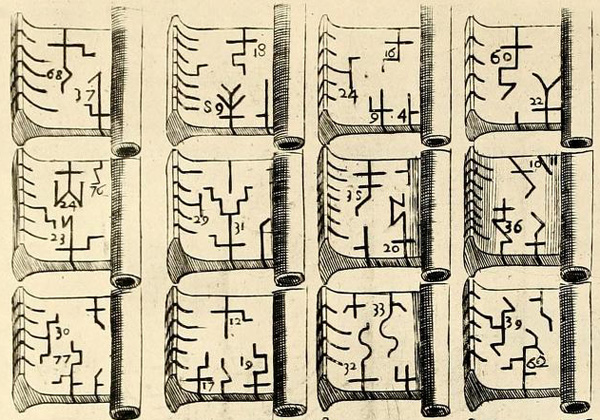

La Fidele Ouverture/CREDIT: blacksmithebooks.comEngraving from Guide for French Locksmiths

During this period in Europe, keys and locks were manufactured by artisans in guilds dedicated to the craft. (The image at left, of designs for key bits, comes from a 1627 French guidebook for the trade.) Because any lock was only as secure as the honor of the craftsman who made it, the guilds had draconian rules about who could make keys, and for whom. One French guild stipulated that a locksmith couldn’t make a key at night or out of sight in a back room, and couldn’t make a key for any lock he didn’t have on the premises, with proof that the man who requested the key was the owner of the lock. If you made a key for the wrong guy, you could be hanged.

-

Jones Collection/V&A Museum.

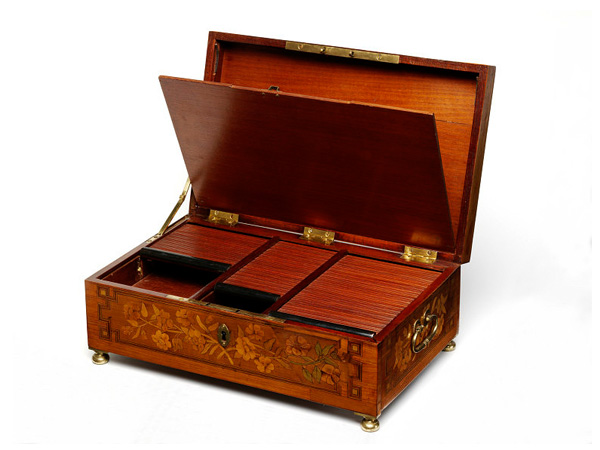

Jones Collection/V&A Museum.French Casket

Dr. Carolyn Sargentson, an art historian, has studied what the key signified to the men and women of Ancien Regime Paris. Wealthy men and women often purchased ornately designed locking furniture—writing desks, armoires, caskets like the one shown here, from the 1770s—that featured secret compartments for correspondence, gems, and other valuables. You might be hiding your trinkets from the servants, or you might be hiding a packet of racy letters from your husband. Keys gave elite women in this period a measure of autonomy and privacy. They wore them in pockets under their dresses, on their person at all times.

-

Metalwork Collection, V&A Museum.

Metalwork Collection, V&A Museum.John Wilkes’ Detector Lock

As locks and keys proliferated across Europe, they became increasingly sophisticated. This 1680 “detector lock,” designed in England by John Wilkes, is a technical marvel. To spring the bolt, you cock the cap of the merry musketeer; to find the keyhole, you slide his leg, hinged at the knee. And each time the door is unlocked, the numbered dial takes note, ticking forward a notch. That means that if you lock up your study when the dial’s at 98 and you come home to find it at 99, you know someone’s been messing around with your stuff.

-

CREDIT: Musee Le Secq des Tournelles; Musée Bricard.

Feisty Locks

Although the ornamentation was increasingly delicate and ingenious, 17th-century locks and keys weren’t much more secure than their medieval predecessors. But the 18th and 19th centuries brought about a new obsession with security. Industrialization made European cities more crowded and helped create a middle class full of people with stuff worth stealing. Theft became more common, and the pressure to thwart it drove locksmiths to new heights. These locks take severe, if somewhat impractical, tacks: Any person using the wrong key in the 1780 lock on the right will find his wrist clamped by the jaws of a fearsome metal lion; anyone jimmying the 1823 lock on the left may get shot by the pistol embedded within it (just barely visible at top right).

-

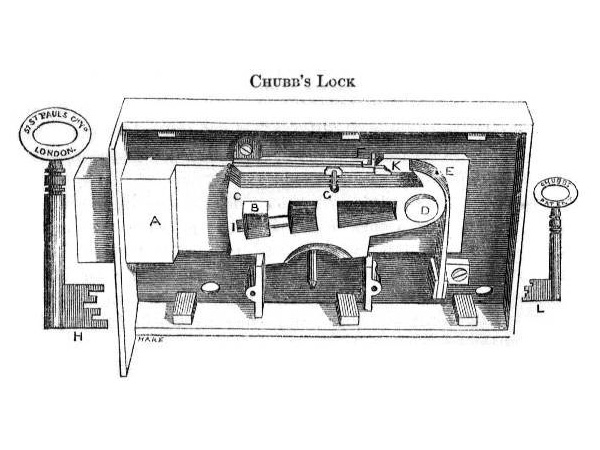

Diagram of Jeremiah Chubb’s Lock, patented 1818, courtesy Oldlocks.com.

Diagram of Jeremiah Chubb’s Lock, patented 1818, courtesy Oldlocks.com.Lock Innovators

Eventually, though, locksmiths came up with more practical ways to stymie thieves. In Britain, a trio of locksmiths—Robert Barron, Joseph Bramah, and Jeremiah Chubb—revived and reinvented the tumbler system used in the ancient world, adapting it to make modern lever tumbler locks that were much harder to pick than the ward locks that had been in use for centuries. A convict on a prison ship in Portsmouth boasted that he could pick Chubb’s lock, but after working on it for several months, he declared it unpickable. It wasn’t until 1851, at the International Industrial Exhibition in London, that the Bramah and Chubb locks were finally beaten, by an American named Alfred C. Hobbs.

-

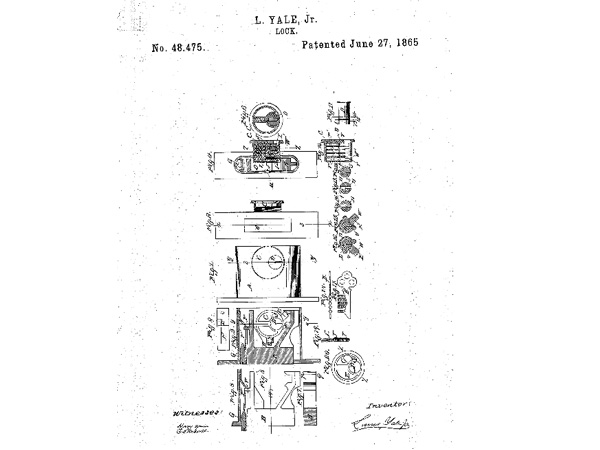

United States Patent and Trademark Office.

United States Patent and Trademark Office.The Father of the Modern Key

Perhaps the most significant change to the design of the modern key was patented by an American—Linus Yale Jr.—in 1865. His pin tumbler mortise cylinder lock put the tumblers and bolt mechanism inside the door itself. The design meant that keys no longer had to be long enough to go through the door entirely, to a bolt mechanism on the other side. As a result, keys became much smaller and thinner.

-

Scan of Slate Design Director Vivian Selbo’s key collection.

Scan of Slate Design Director Vivian Selbo’s key collection.Yale’s Descendents

The majority of the keys used in America today fit pin tumbler locks, and are descendents of Yale’s system. We secure most of our 21st century possessions with technology that hasn’t changed much since the 19th. But the era of the metal key may be coming to an end.

-

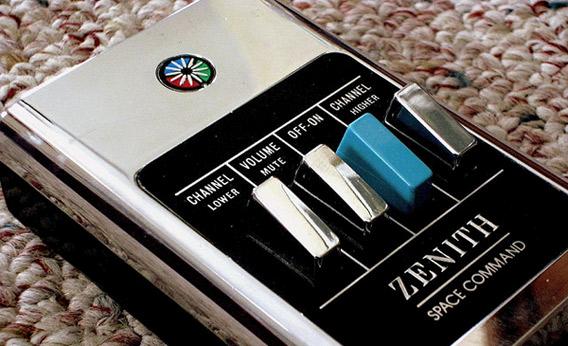

Westin and The Time via CREDIT: Fast Company.

Westin and The Time via CREDIT: Fast Company.Enter the Keycard

First manufactured in the ‘1950s, electronic keys have become increasingly common: Hotels use keycards, private homes use keypads, offices and universities use electronic fobs, some institutions even rely on biometric scans of retinas or thumbprints. The rise of the keycard has been a huge boon to the hotel industry, which formerly wasted energy and time chasing down lost keys. The new swipeable cards—which took root in American hotels in the 1980s—allow hotel managers to reprogram the lock for each guest, which makes rooms more secure. The cards don’t reveal much about the mechanics of the locks they open—the “key” is encrypted in its magnetic stripe—but they do provide a blank canvas for ornamentation.

-

Fobkeyless.com.

Fobkeyless.com.Keyless Cars

Metal car keys are also disappearing. Increasingly, drivers use plastic lozenges that open doors at a distance with the push of a button. Some of these feature a retractable key bit that starts the ignition. But many models now start with the push of a button, as long as the lozenge is somewhere on the driver’s person. In a few years, drivers may no longer know the satisfying feeling of sliding a key into the ignition and turning it til the engine catches. (This shift is good for car companies, who charge a lot more for those fancy doodads than they did for metal keys.)

-

Thinkstock.

Thinkstock.The Keypad

The digitization of security makes it possible to imagine a future where a chip in your wallet gives you access to your home, your car, your office, and the room down in the basement where you keep the bandsaw so the kids won’t play with it. Although electronic systems are more expensive than traditional keys at the moment—and more likely to be found in institutional settings—high-end homes have begun using them. (The same sort of person who would have worn an ostentatious key as a ring in ancient Rome or shown off his nifty detector lock in 1690 would now be likely to tour you around his home pointing out the security cameras, fireproof safes, and digital access controls.)

-

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images.

The Biometric Scanner

But the question with electronic keys—or biometric scans—is who will control the access. For years, locksmiths have shouldered that task, spurred on by thieves to improve their products, careful not to share their secrets too widely. But a card embedded with digital code has as much in common with your e-mail password as it does with your housekey. These new systems have drawbacks—they may be vulnerable to computer hackers or electrical failures. But the new electronic security devices have benefits, too—it’s easier to reprogram a lock when someone’s access privileges change. And there’s one inarguable upside to a world without metal keys: It will be impossible to lose them.

-

More in this series: Read about the book, the office chair, and the other objects featured in our series on everyday design.

Arizona Department of Transportation.

Todd Ehlers/ Flickr.