When we were young and the Internet was too, many of my friends treated it as a laboratory, experimenting with identity. In chat rooms and on message boards they would offer new names, claim different genders, and pretend to be older than they were. This was the early Web’s utopian promise: It seemed to liberate us from the terms and conditions of our “real” lives, setting us free to become whoever we wanted—or needed—to be.

But the Web had terms and conditions of its own, even if we didn’t read them at the time. And instead of freeing us from the real, the Internet has begun to shape it.

Consider the case of Zoë Cat, a former Facebook employee. In an essay posted to Medium (and subsequently republished on Gizmodo), Cat explains that she had fallen afoul of Facebook’s real-names policy, which forces the site’s users to go by the appellation they use offline or face banishment. (Cat welcomed me to refer to her by that name, though she wrote the piece under the name Zip.) A trans woman, Cat explains that she selected her Facebook name years before as she was beginning to transition. In a later post, she added that she subsequently changed her legal name to something else altogether. Nevertheless, she continued to employ the one she had first selected on the social network because “she wouldn’t be recognized by” the newer one. Facebook, Cat wrote, “decided my name was not real enough and summarily cut me off from my friends, family and peers.” She says that Facebook gave her one week to “provide proof of name.” She hasn’t provided proof, and her profile is still active as of Monday afternoon—but that may be because of the fuss her posts created. Regardless of what happens to her profile, the kerfuffle speaks to a broader problem about managing identity in a digital world.

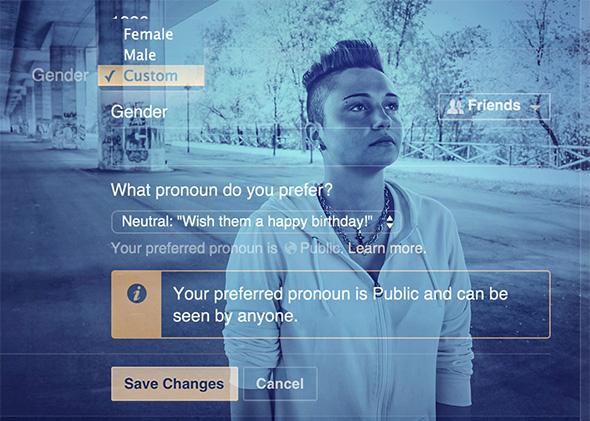

Cat’s story of exclusion stands out in part because she claims partial responsibility for one of Facebook’s most famously inclusive gestures. She writes that during her time with the company, she implemented its custom gender feature, which allows those who don’t identify as “male” or “female” to choose from more than 50 alternate possibilities. (Facebook has neither confirmed nor denied Cat’s assertion.) Now Cat risks banishment from the site for reasons that relate directly to her trans identity—and the hammer struck on the very weekend when celebratory rainbows blossomed across Facebook in response to the Supreme Court’s marriage equality decision.

Cat’s story is not a new one. Facebook has long insisted that its users go by the names they employ in their offline lives. The company operates on the theory that users get more out of the site when they feel like they’re interacting with real people. Cat affirms this hypothesis in her essay, writing, “Creating a social network where people used the names that they were already recognised by has made it more accessible and popular than any other social network in the world.” Accordingly, Facebook seeks to ensure that each profile is clearly and definitively tied to a single, real person, and it associates that reality primarily with users’ names. In this, it’s not entirely alone: Google Plus once had a similar policy, though the company abandoned it under pressure last year.

Social media critics have seized on the real names requirement as a tool of commerce. In his book Terms of Service, Jacob Silverman writes, “The push for authenticity is really a campaign to have every user be immediately identifiable … their whole data self immediately visible to the social network controlling it and selling it back to them in the form of advertising, coupons, and gifts.” When it’s easier to pin you down, it’s easier to sell you to advertisers, and nothing holds us in place more immediately than our names.

Cat, for one, disagrees with Silverman. But whatever Facebook’s intent here, it’s important to recognize that the real names requirement has had a disproportionately negative effect on the site’s LGBTQ users, many of whom have compelling reasons to employ different names online than they do offline. For example, trans women and men worry that it threatens to make them go by names that misgender them, or otherwise call painful attention to their pre-transition experiences. On a different front, drag performers have complained that the regulation prevents them from maintaining profiles under their stage names. For others still, employing a different name on Facebook allows them to remain in touch with their support circles while avoiding harassment or threats. As Meredith Talusan—the trans advocate whose Twitter feed first alerted me to Cat’s situation—observes, “When you’re part of a small minority and are at risk of attack when you walk down the street, online spaces are often the only place where you can be your real self.”

Ironically, Facebook claims that its authentic names policy actually helps prevent abuse. In a recent blog post, Facebook’s Justin Osofsky and Monika Bickert write that it serves to “protect our community from dangerous interactions, like when an abusive ex-boyfriend impersonates a friend to harass his ex-girlfriend, or a high school bully uses a fake name to post hateful comments about a gay classmate.” On first pass, this is sensible enough. The easier it is to associate someone’s online presence with his real identity, the easier it is to hold him accountable for his actions. But the same principle may also make it easier to victimize those who would rather go unseen—whether for relatively mundane privacy reasons, or out of concern for their safety.

Facebook is aware of this problem, but its answer is not entirely satisfying. It believes that users should take advantage of the site’s robust privacy controls, which allow you to tightly regulate who sees your posts, and even how visible your profile is. Even as Facebook has worked to improve these features, this approach puts an undue burden on those who—for whatever reason—have something to hide. In the process, it turns an experience that should be about pleasant communal contact into a process of endless surveillance and restraint.

Further, the very mechanisms by which Facebook enforces its authentic names policy can easily become tools of and for abuse. Facebook does not actively seek out offending profiles—there is, for example, no algorithm to identify the slyly pseudonymous. Instead, it relies on its users to alert the site of others who are in violation. In her Medium essay, Cat proposes that this hands “an enormous hammer to those who would like to silence us.”

Indeed, who would bother to tattle on an actual friend for using an alias? Instead, hitting the report button is most likely to be a vindictive action. Cat, for example, told me that it happened after she “talked about [her] feelings about Pride and how frustrating it was that companies would fly the rainbow flag while having policies that hurt LGBT people.” Shortly after her friends shared these posts—including some in which she talked about the real name policy—someone flagged her profile. Cat believes that the two incidents are linked, writing to me, “I think that one of their friends may have been upset about my comments and reported my name.” If, as Osofsky and Bickert argue, authentic names prevent harassment in one sphere, they may encourage it in another.

Facebook representatives insist that they’re conscious of such issues and are actively working to resolve the problems caused by the authentic names policy. Indeed, they’ve tried to do so in the past. Alluding to protests by drag queens, Osofsky and Bickert write, “Last year we realized that we were making it too hard for people to confirm their authentic identity on Facebook.” Facebook subsequently revised and clarified its names regulations in consultation with LGBTQ groups and activists.

Importantly, the company stressed that an “authentic name” didn’t have to correspond with a user’s legal name, just to whatever his or her “friends call [them] in real life.” Responding to an inquiry that touched on Cat’s situation in a public Q&A session, Mark Zuckerberg affirmed this point. “Your real name,” he wrote, “is whatever you go by and what your friends call you.” Last year, in support of this premise, his company broadened the range of acceptable forms of identification and provided several options for users to present them. Nevertheless, many of those alternate documents are still governmental or financial—library cards and bank statements count among the acceptable items—making them difficult to acquire without a legal name change.

In her public follow-up post, Cat acknowledged that she could have gone through this verification process but that she chose not to—as is her prerogative. Cat has directed her protest at the very existence of the authentic names policy, which she sees as fundamentally pernicious, despite Facebook’s attempts to liberalize it. The trouble, she holds, begins with the very idea of a company deciding what does and does not count as a legitimate name. “Facebook should not be in the business of deciding who is real and who is not,” she told me. In particular, she seizes on its insistence that its users should have only one name, and only one identity to go with it. Calling this “a very WASP notion,” Cat writes on Medium, “Each person has many names, because each person has many contexts and social groups. Like the government, Facebook tries to warp all of these contexts into one identifier.”

The idea that we have many names is not ridiculous. Nor is it absurd to suggest that it might be worth protecting them in their variety. And allowing private companies to police those names is dangerous, not least of all because, as Cat wrote to me, “when they get it wrong they hurt minorities and vulnerable people most of all.” Imagine a young person from a conservative background who begins to question his sexuality. He can’t safely share these thoughts with his friends and family, but he doesn’t want to fully shut them out of his life, either, so rigid privacy filters aren’t necessarily an option. Building another identity—beginning with another name—might offer him a degree of comfort and safety as he works to find a new support system for his new needs. This kind of plural identity, a plurality the Internet once welcomed, is exactly what Facebook denies its user base.

For its critics, Facebook feels threatening in part because it actively sets the terms of identity instead of merely reflecting them. In a point-by-point refutation of Zuckerberg’s recent comments, Cat writes that the site has “set itself up as a gatekeeper to determine our realness.” By insisting that we settle on one version of our lives, and that we tell only one story about ourselves, Facebook effectively makes that story the real one. And because the site is increasingly central to the ways we live, work, and even love, simply logging off is rarely an option. As the literary critic and social theorist Michael Warner shows in Publics and Counterpublics, alternate cultural spaces were once the crucible of LGBTQ identities. Today, settling on a single identity, more or less in advance, may be the price of appearing in public at all, making the contemporary equivalents of such spaces less useful than they once were.

Facebook evidently means well—and there’s no reason to think that its employees don’t want the best for their LGBTQ users. The company’s willingness to work with Cat on the custom gender policy provides ample evidence of this, as do its ongoing attempts to revise its policies. Wanting the best, however, doesn’t necessarily mean understanding what’s best, and it’s not clear that Facebook does. For Cat and others, pushing back against the site’s regulations is about giving those who don’t yet know their names the space to find them, and those who do the room to live according to their desires.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.