Remember when Mark Zuckerberg didn’t believe in privacy? When he argued that it was “no longer a social norm”? When Facebook employees wouldn’t even use the word “privacy” at a forum about the future of privacy?

That was then. Now, it seems, privacy is back—not just as a social norm, but as a business model.

On a conference call with investors on Wednesday, Zuckerberg singled out privacy features and private services like messaging and anonymous logins as keys to the company’s future growth. Why? “Because,” he said, “at some level, there are only so many photos you’re going to want to share with all your friends.”

He’s right. From WhatsApp to Snapchat to bitcoin to Secret and Whisper, privacy is as hot today in the technology industry as “sharing” and “openness” were four years ago. And Facebook intends to capitalize on it—provided it’s not too late.

To be fair, Facebook’s about-face on privacy has been in the works behind the scenes for a while now. I met in March with a pair of managers from the company’s “privacy product and engineering” team, which was formed in early 2012. Their job is to think about nothing but privacy all day. Making privacy a product in itself, like the news feed or Facebook Messenger, “allowed us to think about it a little more holistically, in a little more of a user-centric way,” product manager Mike Nowak told me.

In the past six months, that shift in focus has become apparent.

The clearest sign came in February with Facebook’s $19 billion acquisition of WhatsApp, a globally popular private-messaging app. Then, in March, the company trotted out the privacy dinosaur, a little blue avatar that popped up on users’ news feeds to make sure they weren’t accidentally oversharing.

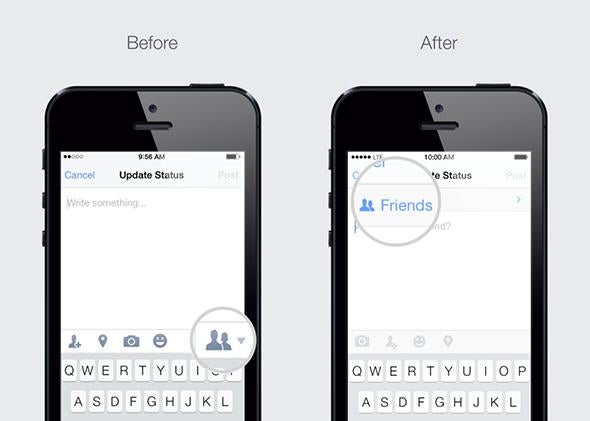

April brought a new “anonymous login” feature that will allow Facebook members to verify their identity to apps and websites without giving away any personal information. In May, the company quietly took a step that few would have imagined four years ago, when “openness” was all Zuckerberg could talk about: It changed the default audience for new members’ posts from “public” to “friends.” And just this month Facebook rolled out a “save” function that lets people bookmark posts and content from around the Web—without revealing them to anyone else.

It was that flurry of privacy features and services that prompted one astute investor to ask Zuckerberg on Wednesday whether the company was undergoing “a strategic shift in thinking or tone with regard to privacy.”

Usually, Facebook spokespeople reject the premise of such questions. The company has always cared about users’ privacy, they insist—it’s just a matter of evolving and improving over time.

On Wednesday, though, Zuckerberg rose to the bait. Perhaps he was feeling particularly confident after Facebook’s earnings crushed Wall Street’s expectations yet again. (Facebook’s stock is now the top performer in the S&P 500 over the past year.) For whatever reason, he seized the opportunity to launch into a monologue about the history and future of privacy on Facebook. You would not have guessed that this was the same man who had dismissed privacy as outmoded just a few years ago.

I’ve transcribed his full response below, because I find it so interesting in contrast to his prior statements. But if you want the tl;dr version, just focus on the three passages I’ve bolded and italicized.

That’s a really important question, and I think it’s something that is misunderstood about Facebook.

One of the things that we focus on the most is creating private spaces for people to share things and have interactions that they couldn’t have had elsewhere. So if you go back to the very beginning of Facebook—rewind 10 years—there were blogs and things where you could be completely public, and there were emails so you could circulate something completely private. But there were no spaces where you could share with just your friends.

It wasn’t a completely private experience, but it’s not completely public: It’s 100 or 150 of the people that you care about. And creating that space, which was a space that had a kind of privacy that no one had ever seen before, was what enabled and continues to enable the kinds of interactions and other content that people feel comfortable sharing in this network.

So we’re looking for new opportunities to create new dynamics like that and open up new, different private spaces for people where they can then feel comfortable sharing and having the freedom to express something to people that they otherwise wouldn’t be able to. It’s one of the reasons I’m personally so excited about messaging. Because at some level there are only so many photos you’re going to want to share with all your friends.

I mean, obviously, we still think there’s more to do there. But the amount of messaging and how quickly we see that growing, it’s crazy. There is just a lot more that people want to express and that they need the tools to express with smaller groups of people—not just one person at a time, but small groups as well. Things like anonymous login totally unlock different behavior. So we view our jobs as, like, very fundamentally providing people with these spaces and tools. Which is very different from how a lot of people think about what Facebook is.

What Zuckerberg doesn’t mention here is that this isn’t just different from how “a lot of people” think about Facebook. It’s also quite different from how Zuckerberg himself used to think about Facebook. There seems to be a bit of history-book-rewriting going on when Zuckerberg explains how privacy was fundamental to Facebook’s success from the beginning.

But that doesn’t make it untrue. Anyone who joined Facebook early on knows Zuckerberg is right that a modicum of privacy was crucial to Facebook’s early success. As former employee Kate Losse chronicled in her 2012 book The Boy Kings, the knowledge that the site was open only to students of elite colleges emboldened people to post things they’d never have dreamed of sharing with the public.

In fact, I’d argue that privacy remained important to the majority of Facebook’s users all along—even through the years when Facebook itself didn’t realize it.

Facebook has succeeded as a business by pushing the boundaries of what people are willing to share, but on several occasions it pushed too far. Users pushed back, and Facebook adjusted, but the missteps did lasting damage to the company’s reputation. It’s now widely understood that no one should post things on Facebook they wouldn’t be comfortable revealing to a wide audience.

Belatedly, Zuckerberg and company are trying to change that. They’ve come to understand that their targeted-advertising business doesn’t necessarily rely on people sharing things with the public. It just relies on them using Facebook’s services as much as possible, so that the company’s software can keep refining its understanding of their behavior and preferences. As Zuckerberg now recognizes, they won’t do that unless they trust Facebook to keep some things to itself.

It’s not inconceivable that people would place such trust in a company that harvests their data for targeted ads. Look at Google, whose hundreds of millions of Gmail and search users have generally accepted a bargain in which software “reads” their most intimate communications, but other humans don’t (except, you know, when they do).

Facebook’s first mega-fortune was built on the backs of extroverts. If there’s to be a next one, Zuckerberg is going to have to get introverts to open their accounts—and their wallets—as well.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.