Thirsty West: The End of the Road

Oregon may be California’s agricultural future.

Photo by Eric Holthaus

SHERIDAN, Oregon—In the Thirsty West series, I’ve tried to look at the immensely complicated issue of Western water in a time of transition: Rapid urbanization, continued dependence on industrial agriculture, and global warming are simultaneously forcing a rethinking of the basis of growth for nearly half our continent. Without enough water, it’s hard to sustain human civilization.

But how much is “enough”? There surely is enough water for urban dwellers to survive out West, even with increasing numbers. The problem lies in using water in ridiculous ways.

The future of water issues in the West will be decided by agriculture. Whether it’s the perplexing persistence of wasteful urban agriculture (grass lawns) in Los Angeles and Las Vegas or our country’s dependence on growing huge quantities of food in California’s reclaimed Central Valley desert, agriculture is the beginning and end of any discussion of Western water. For example, agriculture currently uses about 80 percent of California’s developed water resources each year. If you add lawns (which use about half of all city water) into the mix, that figure jumps to 90 percent.

For years, we’ve been told by corporate farms from Kansas to California that they’re “feeding the world,” so they deserve every drop of water currently coming their way, global warming and dwindling aquifers be damned. After driving through the West for a month—including California’s Central Valley, the belly of America’s agribusiness beast—I think they’re right. Farmers deserve to keep getting the majority of our water. But just not the way they’re currently running things, which is skewed by huge subsidies at odds with public health.

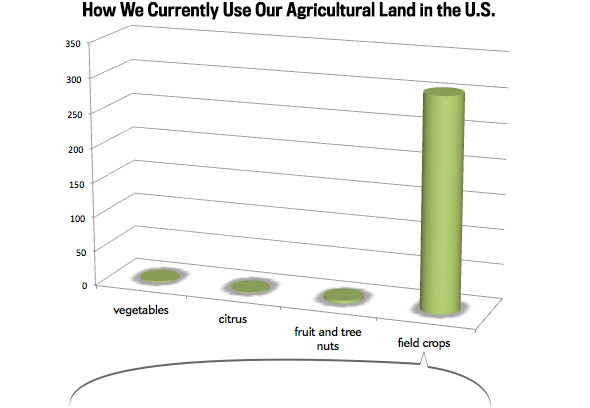

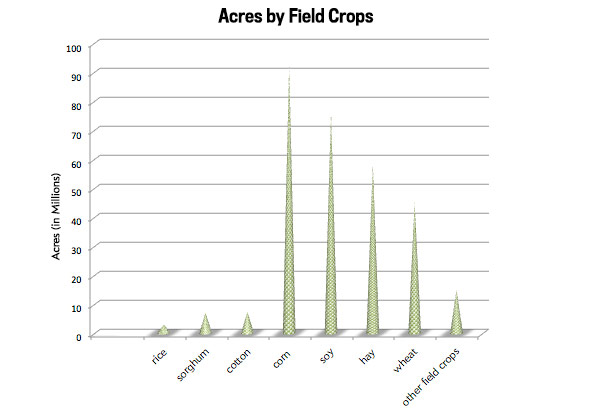

Here’s a snapshot at how we currently use our agricultural land in this country:

That’s right: We use 200 times the land on commodity agriculture (think: high-fructose corn syrup and hamburgers) as we do on all vegetables combined. No wonder there’s sticker shock in the organic produce aisle. There’s so much waste already built into the system.

The world needs much more than just ethanol and cheap grain for livestock feed. To get there, we’ll need massive changes in the way we do agriculture in this country. These misplaced priorities are helping to overwhelmingly subsidize meat, dairy, and grains, while leaving vegetables, nuts, and fruit to increase in relative price and making it hard for small farmers to compete.

California’s agricultural riches are mostly due to the combination of favorable climate and historical happenstance. As a result, practically everything we think of as “food,” from avocados to zucchini, is grown there in massive quantities. But there’s no reason why other states can’t mimic its agricultural success in growing food people actually eat. Sooner or later, they’ll have to: The dwindling snowpack in California’s Sierra range will see to it.

On the fringe of modern “conventional agriculture” lies the growing permaculture, local, and organic movements. In 2013, the Department of Agriculture estimates, organic food made up just 4 percent of food sales. But if you take the long view, agriculture has always been local and organic. What we’re witnessing is the start of a massive mean reversion: Farmers are finally learning that it’s better to work with nature, not against it. Irrigating the desert with dwindling groundwater simply can’t continue indefinitely.

Small farms are more productive and more nutritious per acre. The problem is, there just aren’t many small farms left in the country. And another problem: As much as advocates wish it were so, organic farming still can’t feed the world, at least not in its current state. There’s an inevitable yield trade-off when you stop pumping crops full of chemicals and imported water.

As my wife and I completed our Thirsty West road trip, we visited Joshua Simonson’s brand-new chicken farm in the Willamette Valley, one of a growing wave of new farmers with a different set of priorities.

I sat in Simonson’s front yard, with a dozen or so heritage breed hens roaming freely about. As Simonson’s wife and toddler chased them, he reflected on his motivation for starting such a seemingly chaotic endeavor:

Photo by Eric Holthaus

My family’s been in the Willamette Valley for a long time, we moved here from Iowa in 1917. I’m the fourth generation. I grew up as a grass seed farmer, and I never wanted to be a farmer. My dad said we were feeding the world, and I just never saw it. I didn’t want to grow lawns. That’s not farming.

While working at a natural foods market in Portland, he was appalled by what he considered to be a void in Oregon’s agricultural landscape: There aren’t that many farmers left in this famously fertile area that are growing actual food. (Simonson’s neighbors are mostly vineyards, grass seed farms, and landscaping-tree nurseries.) So he returned to farming, just in a different way. He’s motivated by his time working on his father’s farm as a kid:

What I didn’t like about their style of farming was you sat in a tractor and went around in a circle all day long. We’d apply more and more chemicals. It disconnects you from the soil and what you’re doing.

I was seeking more adventure in my life. What we’re doing now is what my great-grandfather did.

When he went to the bank to get funding, he says, “they laughed at me because we weren’t farming grass seed,” the way all of his neighbors do. But he’s had help: He attributes his start at least partially to Friends of Family Farmers, an advocacy organization in Oregon that helps partner aspiring small farmers with landowners. That’s how he’s leased his current plot of land, a retired grass seed farm he’s turned into a pasture for hundreds of free-range chickens he sells to restaurants and farmers markets in Portland.

As we walked from the farmhouse toward the four huge chicken coops he designed himself from old shipping containers, he talked freely about the challenges he’s faced in just the first few months.

Simonson feels the headwinds of a system built to support industrial agriculture in a deeply personal way. “It’s not at all what we expected it to be. We’re going to write a book someday called Everything We Thought We Knew About Farming Is Wrong.” Regulations from the Food and Drug Administration have limited the size of his flock, and he’s had trouble sourcing corn-free, GMO-free chicken feed in line with his values.

Photo by Eric Holthaus

Simonson has noticed the effect that industrial farming has had on local water resources, too. In the past year or so, the California drought has started creeping northward, and Simonson said that’s only heightened what he sees as a long-term shift in the local climate:

Farmers here get paid by the government to get these huge irrigation systems, and they use them constantly, where they didn’t use them before. They water dirt fields, just to keep their water rights. You have to keep irrigating—even on rainy days—or you lose it. I had never seen that before.

The Willamette Valley was once the American agricultural ideal, the last stop of the Oregon Trail. Now, the water table is dropping, and things are quickly changing.

We’re lucky. We bought a semi-truck load of feed before the drought really got bad. But pretty soon, we’re going to have the climate of the Central Valley where you just came from. We’re going to have the same water problems. People are going to have to learn that you can’t keep doing things the same old way. I’m going to have to learn to grow different crops here. Just like any ecosystem, diversification protects you.

Simonson is one of the first to put his money where his mouth is. But as his story embodies, change won’t be easy.

While it’s a beautiful idea, the romantic idea of organic agriculture as a big red barn on the hill with cute little piglets and lambs living together in harmony needs a wake-up call. At the end of the day, farmers like Simonson still have to pay their bills.

What we need is a better way: a hybrid system of organic and industrial agriculture that will actually be profitable enough for small farmers to return to the fields. The cooperative movement is an example of a possible bridge, but people much smarter than me are going to have to figure out the details.

My wife and I moved from Arizona to Wisconsin in part because of water. Though we get droughts here, too, southwest Wisconsin is reliably green and lush each summer, with a long growing season. Wisconsin also has the highest number of organic farms of any state (except California, of course) and is a hotbed of the local foods movement.

Now that we have a backyard of chickens, raised vegetable beds, and bees, we can offset a tiny bit of what we would have bought at the store, but I’m under no illusions that backyard gardens will replace industrial agriculture anytime soon. In our 21st-century world of extremely specialized skillsets, not everyone is going to have the time or desire to sustainably harvest their own spinach. You do it because you love it, not because it’s the cheapest or most efficient way to feed your family.

At the end of our road trip, I’ve gained a much greater appreciation for the complexity of water issues in the West. Taken as a whole, there’s a sense of foreboding, but also hope. Thanks to the current drought, the West is at a crossroads. Decisions we make in the next few years will determine how long it remains Thirsty.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Tucson, Ariz.

Tucson, Ariz.

Nogales, Ariz.

Las Vegas, Nev.

Death Valley

Sequoia National Forest

Hanford, Calif.

Denair, Calif.

Tulare, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Sheridan, Ore.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.