Thirsty West: Lose-Lose Situation

Excessive environmental regulation is ruining agriculture in California.

TULARE, Calif.—Signs of drought are everywhere in California’s agricultural Central Valley. On my monthlong multistate road trip through the drought-stricken West for Slate, there was nowhere that produced more gasps per square mile as here.

Courtesy of Eric Holthaus

Tulare Lake was once the largest body of fresh water west of the Mississippi. But it is no more. This lake (and surrounding ecosystem) was one of the first major casualties of Central Valley agriculture, way back around the turn of the previous century. Farmers from the East settled here after the Civil War, and maps from that era show the lake with roads drawing closer to the tantalizing water source. Technically, four rivers still connect to this lake bed, but none actually make it here with water anymore. The lake has partially reappeared at times, as recently as 1997’s El Niño–driven floods, which couldn’t be contained by the maze of canals and river diversions that feed local agriculture.

One afternoon, I drove out to the now-dry lake bed to have a look around.

In some places, it was like a Plato’s ideal of drought. Surprisingly, there were more green fields than fallow ones, fed in this driest of dry years by groundwater pumping. But the empty fields felt ominous. I encountered more than one dust storm on my way back, passing through soil blown into the air on a warm and windy March day.

This year, water that would have been diverted to thirsty fields never came. That’s mostly due to straight-up lack of water. After all, the state is in the midst of months and months of practically no rain and currently has the slimmest snowpack on record—just 4 percent of normal as of Tuesday. But part of the dwindling water supply has been kept in streams, to keep sensitive rivers flowing. According to some farmers here, that means the extreme lack of water is partly the government’s fault.

They’ve got a case.

During a year of record-breaking drought in California, water is about as political as you can get these days. Cries of mismanagement of the state’s slim water resources abound.

Courtesy of Eric Holthaus

For Gavin Iacono, a deputy agricultural commissioner for Tulare County, it’s a matter of priorities. He says California’s booming urban areas have lost touch with the reality of agriculture. “I call it ‘Safeway-itis’. Most people in cities don’t have direct contact with the land, or the way their food is produced anymore. It’s like, ‘Who cares about farmers? I can just get my food from the grocery store.’”

Iacono, a cowboy-booted and belt-buckled figure who “used to rodeo for a living,” is a charismatic force of nature in his tiny office, and would fit right in in Texas. With a wide smile, he recalls his days touring the competitions around the West, when people would ask questions like, “I didn’t know you had cattle in California! Do you know how to surf?”

He says farmers like him often get a bad rap in the state:

Some of the biggest environmentalists you’ve ever seen are farmers and ranchers. I mean, we’re farming a desert. We’re hyper conscious about our water. You can’t use it up until there’s nothing left. They’re not making any more ground.

Here in the Valley, you’ve got to balance that need with everything else. When we irrigate, where does the excess go? It goes into the ground. When cities waste water, it goes to a treatment plant, it might be recycled, maybe used for landscaping.

The agricultural advocacy in his family runs deep. Iacono’s grandfather used to boast: “If I knew I would die today, I would go down and blow up the pumping station to L.A.”

Fighting over water has long been an unofficial pastime in the West. The landmark Supreme Court case Arizona v. California (actually a series of decisions spread out over some 75 years) put a cap on how much water could be drawn from the Colorado River after Arizona sent an armed militia to the state line to protest the construction of a dam in 1934. In the 1970s, major environmental regulations like the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act placed further limits on the amount of water that could be diverted for agricultural use.

Of course, the farmers fought back. Some of the wealthiest and most powerful farmers in the country are right here along the shores of old Tulare Lake. During the Bush administration, these farmers won a major victory in Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District et al., v. the United States. The government was ordered to pay a multimillion-dollar settlement for withholding irrigation water to protect endangered fish during a drought.

Courtesy of Eric Holthaus

Take the tiny Delta smelt, for example: Since this fish hit the state endangered species list in 2010, water-pumping from the San Joaquin–Sacramento River Delta has been curtailed in an attempt to restore the sensitive ecosystem of the West Coast’s largest estuary. Farmers throughout the state are being forced to fallow fields in order to save it. Back then, the Wall Street Journal ran an op-ed with the title “California’s Man-Made Drought.”

And still the battle goes on. During the middle of my trip, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a ruling limiting water pumping to protect the fish, dealing a major blow to agricultural interests in the state. The issue has become so politically charged that you can’t talk about water in California anymore without talking about the Delta smelt.

Problem is state environmental regulators are fighting a losing battle. Despite the restrictions on agricultural water use, the Delta smelt’s population is still in a freefall. Last year, populations of the fish reached a new record low since it became endangered, down more than 90 percent over the past 20 years. Environmentalists argue that the smelt is much more important than its size and is an indicator species for the ecosystem health of the entire region, including salmon and migrating birds. They say huge corporate farms are pulling out all the stops to grab water from every source they can find, even in spite of a major drought.

Courtesy of Eric Holthaus

They’ve got a case, too. As I wrote in my previous Thirsty West, agriculture already uses 80 percent of the state’s water, with a significant portion of that destined to support cash crops—like almonds—grown for export. It makes sense to ask farmers to do more with what water they already have.

Some solutions on the table are almost laughably outrageous: A multibillion-dollar proposal by Gov. Jerry Brown to build aqueduct tunnels under the Delta so as to not interfere with fish habitat has advanced to the planning stages. A plan to load salmon in trucks and haul them upriver by convoy is already underway. An $11 billion “water bond” is scheduled to go in front of California voters in November.

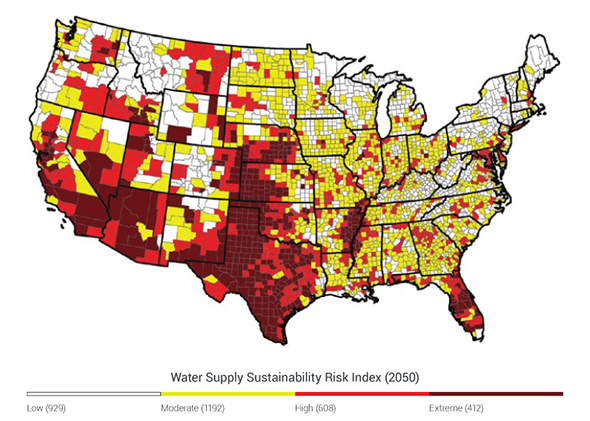

Unfortunately, both sides in this debate aren’t yet facing the grim reality of the future. Sensitive species like the Delta smelt are going to go extinct due to climate change. Fighting against saltwater intrusion, snowpack loss, and warmer temperatures is a losing battle with or without environmental regulation (though if done well, environmental regulation will blunt this change). Some ecosystems, like the Delta, are going to change in fundamental ways in the coming decades. The state can’t bring its economy crashing down in the process.

It’s easy to argue that the point of the increasing slate of environmental rules in California is to help reclaim what was once here, if not for an overreach of human activity. Just because humans carry the biggest sticks (and most powerful river-diverting machinery) doesn’t mean we get to wipe out entire species. It’s not that the Delta smelt is a lost cause. But in cases like Tulare Lake and the Delta, reclaiming any semblance of what once was may be unachievable.

Still, Iacono is optimistic the problem will be solved, one way or another. He says if the current drought doesn’t force action, some future calamity will. “At some point we’re going to hit that tipping point, but of course we might get regulated out of ag before that happens. California might go back to being a desert again."

* * *

In my next stop on the Thirsty West road trip, I'll visit a farmers market in Oakland to get a sense of how urban Californians are dealing with the drought.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Tucson, Ariz.

Tucson, Ariz.

Nogales, Ariz.

Las Vegas, Nev.

Death Valley

Sequoia National Forest

Hanford, Calif.

Denair, Calif.

Tulare, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Sheridan, Ore.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.