Get Used to the Flames

California’s “fire season” is basically year-round now.

Photo courtesy John Newman/U.S. Forest Service/Wikimedia (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zaca3.jpg)

HANFORD, Calif.––Where there’s drought, there’s fire.

At least that’s been the case this year, one of the driest in California state history. Through mid-April, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, there have already been nearly 1,000 fires in 2014, not counting those on federal land. That’s double last year’s number over the same time period, and nearly three times the five-year average to start a year.

And “fire season” hasn’t even officially started yet.

From the Wall Street Journal:

Since January, 200 seasonal firefighters have been added to state firefighting ranks in Northern California, far ahead of the region's typical June start to fire season. To the south, where fire season usually arrives in May, state-operated fire stations in San Diego, Riverside and San Bernardino counties are already operating 24 hours a day.

The exceptionally dry conditions have turned the state into a tinderbox, ready to ignite even in months that are typically cool and damp.

In December, a fire near Big Sur burned a patch of forest that hadn’t been touched by flames in more than 100 years. (Among the casualties: the local fire chief’s own home.) In January, a fire in Glendora burned 1,900 acres in the outskirts of Los Angeles. In February, mudslides related to the wildfire forced another round of mandatory evacuations for the Glendora burn area.

Those fires came amid summer-like conditions of hot temperatures and low humidities during what is typically the wettest time of the year. In short, perfect conditions for fire. From Al Jazeera America:

“This is unprecedented,” said Capt. Michael Mohler of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Current conditions are as severe as during the hottest summer months, and Cal Fire is bracing for the worst. It has already brought in 125 additional firefighters, who normally come on board when fire season starts in late May in the North and in June in Southern California.

Facilities where firefighting aircraft are based usually close in the winter. Not this year. “All of our aircraft are running this time,” Mohler said. “Aircraft statewide, all the way from San Diego to Chico.”

A new study released this month shows large fires in the western United States are increasing in frequency and total size, a trend the study’s authors attributed to “changes in climate, invasive species, and consequences of past fire suppression.”

The new research finds that, in aggregate, wildfire burn area in the West is increasing by more than 87,000 acres each year—an area twice the size of Washington, D.C. It’s a trend that shows no signs of slowing.

The finding is in line with previous research that showed the average length of the Western wildfire season has increased by an astonishing 78 days since 1970. The biggest changes have come in regions where warmer temperatures have caused the spring snowmelt to come earlier, winnowing away winter.

Just like California this year.

This week, in its second episode, Showtime’s new climate-change-focused docu-drama Years of Living Dangerously featured former California Gov. Arnold Schwartzenegger deployed with a fire crew in Idaho.

The money quote: “Governor, you have to understand there really is no fire season. The fires are gonna be all year round.” That’s the new world we’ve created.

California’s now buried deep in its worst drought in half a millennium, with snowpack at record lows as the summer months loom. What’s the worst that could happen? On my drought-themed road trip, I decided to investigate.

At the National Weather Service office in Hanford, meteorologists forecast weather conditions for the southern and central Sierra Range, from Yosemite to Bakersfield, covering some of the biggest trees in the world. Along with the firefighters themselves, these scientists are at the front lines in anticipating incendiary weather conditions. “Fire season usually starts in June. This year, it just seems like it never ended,” said Cindy Bean, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Hanford. When an especially big blaze is spotted, meteorologists like Bean are occasionally dispatched to the scene. Last year was her final fire season, after working in the fire camps for 15 years. For Bean, working in such an extreme environment was addictive.

“You start getting into the nuance of the mountains and the fuels and the weather. It starts to make sense, and you get hooked. You get instant feedback when you're out in the field. It really does help you become a better forecaster.” But fast-changing conditions can put people in the fire camp on edge. “During the Zaca Fire down in Santa Barbara County in 2007, a lighting strike in the middle of the night scared everybody.” That fire went on to burn nearly a quarter-million acres.

But this year’s been weird. An oddly summer-like weather pattern hit the Sierras from Jan. 17–23.

Bean recalls: “We had a strange low pressure system that retrograded. When the winds become offshore, humidity dropped and the temperature spiked. We were forced to issue a Red Flag Warning for wildfires. It’s the first time I've ever done that [in January] in the 19 years I've worked here.”

It wasn’t just the strange weather that prompted this year’s rare January fire season. After years of drought, the trees here are ready to ignite.

One of the reasons this winter’s fire season was so bad has to do with the way firefighters attack megafires in the summer. There are simply not enough people to extinguish every last smoldering stump in a fire roughly the size of New York City, like last year’s Rim Fire which burned for months into Yosemite National Park.

Instead, firefighters contain the perimeter of the fire, and plan on the winter snows and rains to do the rest. Problem is, winter didn’t show up. “What we saw this year was, a couple fires rekindled themselves. The fires came back to life," says Bean. Zombie fires, like the one in Sequoia National Forest this January, could happen more often in coming years as climate change accelerates. “That one was burning around some snow patches."

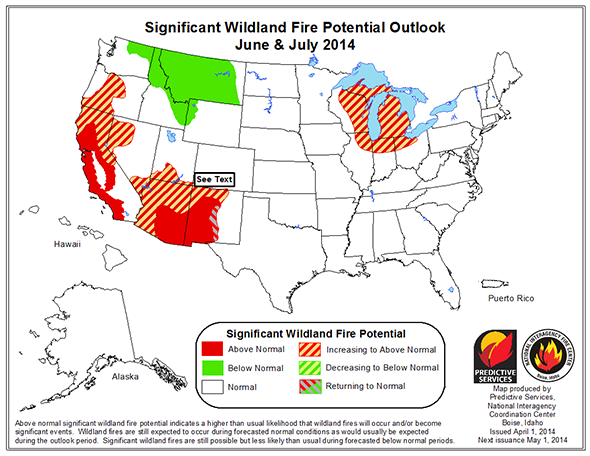

Graphic courtesy National Interagency Coordination Center

Essentially, what we’re seeing here is evidence of the gradual northward migration of entire ecosystems in a warming world. Tree species that aren’t adapted to the warmer and drier weather become susceptible to pests—like the pine bark beetle that has devastated Colorado forests—and eventually die out. When they do, they become kindling for forest fires.

In 2014, this process is happening in the context of one of the driest stretches of California history. So, how bad could it get? Bean’s tongue-in-cheek answer:

“This year has a potential to be an interesting fire season."

* * *

This year could be interesting for California farmers, too. As the leading agricultural state in the country, California produces half of the U.S.-grown fruit, nuts, and vegetables. Only problem is, this year, there’s no water.

That dilemma will be the focus of my next Thirsty West.

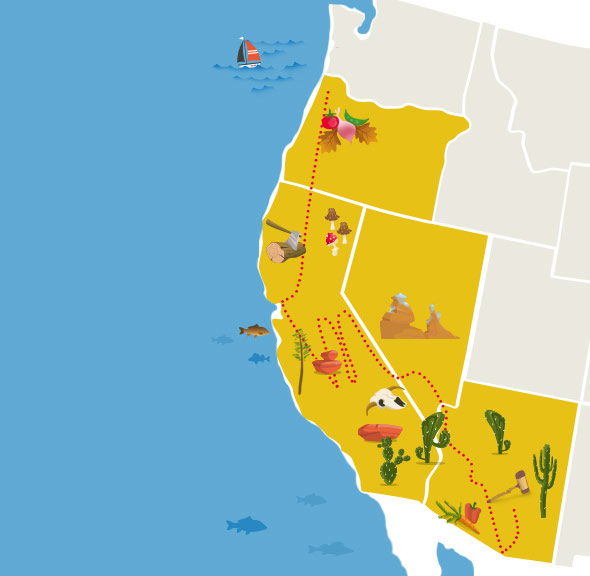

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Tucson, Ariz.

Tucson, Ariz.

Nogales, Ariz.

Las Vegas, Nev.

Death Valley

Sequoia National Forest

Hanford, Calif.

Denair, Calif.

Tulare, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Sheridan, Ore.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.