The Thirsty West: What Drought?

Mexico’s desert farms are booming.

Photo by Eric Holthaus

NOGALES, Ariz.—Here on the U.S.–Mexico border, crazy things happen this time of year. Lots of border towns have some pretty weird quirks, sure, but when it comes to North American food policy, there may be no place stranger than Nogales.

This hilly town serves as the primary gateway for tomatoes, corn, melon, and other fruits and vegetables traveling from Mexico to the United States. In fact, 60 to 70 percent of winter produce for consumption in the United States visits this town first, according to the Fresh Produce Association of the Americas, an industry group. If you’ve had fresh veggies this winter, odds are they came to your plate via a truck that passed through Nogales. The rest comes from Florida or passes through other border posts.

The steady stream of truck traffic is most impressive on “produce row,” a frontage road paralleling Interstate 19 where most of the warehouses are located, just a few miles north of the border. The region is in the final stages of a border crossing expansion that will more than double the number of trucks that can pass through this area. When completed later this year, Nogales will be able to handle commercial border crossings at a rate of nearly three trucks per second.

These are the crazy lengths to which our globalized food system goes to deliver fresh produce out of season.

“The ability to get that produce to the market is improving. All these U.S. companies are investing in farms in Mexico,” says Lance Jungmeyer, president of the Fresh Produce Association of the Americas. Technological advances in drip irrigation, greenhouses, and genetically modified seeds have boosted Mexican vegetable production in recent years. “Effectively, that means the growing season [in Mexico] keeps getting longer—a few weeks earlier, a few weeks later—each year.” The “winter season” for Mexico currently stretches from January to June.

And now, with the California drought putting extra pressure on farmers there to fallow vegetable fields, Nogales could be in prime position to cash in.

Jungmeyer explained the farmer’s drought-altered calculus north of the border: If a California farmer has little water, he has to prioritize. Fruits and nuts that grow on trees will take precedence. If a farmer usually grows both bell peppers and almonds, for example, he’ll likely fallow the pepper field. Instead of being grown in California, those peppers will probably be trucked up from Mexico (and through Nogales).

This time of year, the trucks crossing over from Mexico are filled with squash, melons, corn, and countless other fresh foods more typically found during the midsummer months in the eastern United States. But here in Nogales, tomatoes are king.

In 2011, New York Times writer Elisabeth Rosenthal examined the extravagance of sourcing organic tomatoes from the Mexican desert in midwinter. Her piece was summarized by Mother Jones in 2012:

In addition to lacking water, desert land is also deficient in organic matter: decayed plant material that gives soil tilth and the ability to hold nutrients. Just how stark is the landscape on which these tomatoes are being grown? According to Rosenthal, growers in Baja “describe their toil amid the cactuses as ‘planting the beach.’ ”

When I was a graduate student at the University of Arizona in Tucson—which, by the way, is having water issues of its own—I contemplated devoting my entire Ph.D. to the many tomatoes passing through Nogales. The U of A recently completed a comprehensive study on the cross-border economic implications of this exact phenomenon. So, I was excited to visit for the first time earlier this month as part of my Thirsty West series on Western water issues for Slate.

But everyone is so busy that it was tough even getting interviews this time of year. “This is peak week of peak tomato season,” said Javier Badillo, general manager of Delta Fresh Produce, a distributor based in Nogales, as we briefly met in his office.

When we followed up by phone the following week, Badillo explained that this year, the trucks are especially backed up because of the winter weather on the U.S. East Coast—the biggest market for fresh Mexican produce. With ice-covered interstates hampering travel, deliveries have been tricky or even impossible. Supermarkets haven’t been able to sell as much, either, with families sticking home, opting for canned goods instead.

As a result, warehouses here at the border are overrun with tomatoes at the moment. But that bottleneck should be temporary, since drought-stricken California fields won’t be able to produce as much as normal.

Photo by Eric Holthaus

So will Mexico become the long-term source for most of our tomatoes? This year may just be a lucky one for farmers south of the border. After all, there’s been extreme weather in the fields of west Mexico, too, in recent years. Farmers have alternately battled frosts and droughts. Last fall, twin tropical storms hit nearly simultaneously from each coast, prompting flooding concerns. “It’s like gambling in Las Vegas,” said Omar Sanchez, a sales representative for Sandia Distributors, which—as the name implies—deals mostly in watermelons.

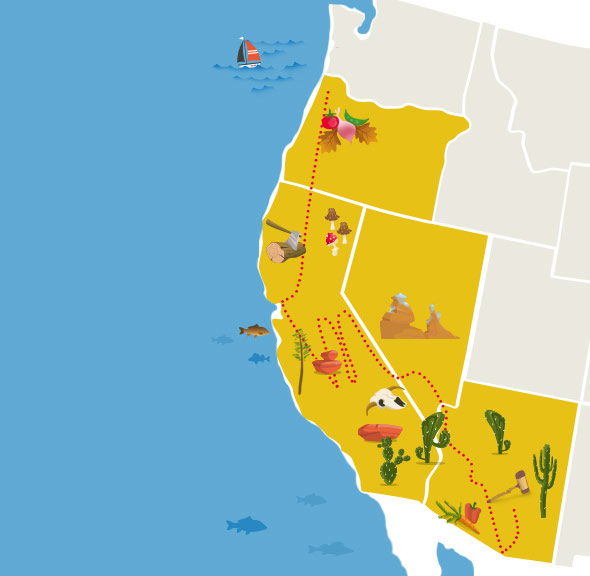

As drought deepens across the Southwest United States, the region is facing hard questions about the future viability of agriculture in one of the country’s richest growing zones, as I described in my intro to the Thirsty West series.

As the climate continues to shift, the global food system keeps growing in complexity. That’s forced massive investment, typically by U.S.-owned companies, in Mexican agriculture. (Companies are also drawn to Mexico because of its relatively lax environmental regulations and better labor supply, says Jungmeyer.)

But drought or no drought, there may not be enough water to go around in the arid growing regions of west Mexico, either. Essentially, the United States is exacerbating Mexico’s own H2O issues by importing millions of tons of water from Mexico in vegetable form. It’s not just agriculture, either: Other U.S. companies with operations in Mexico—like car factories—require water, and lots of it.

Jungmeyer laments this ongoing battle: “When push comes to shove, ag is always going to get the short end of the stick. There’s this perception that ‘Oh, you're just growing things in the dirt; what you're doing doesn't matter.’ It is a sad state of affairs whether you’re on the north or south side of the border.”

As water becomes a bigger sticking point, Jungmeyer predicts a continued massive rebalancing of agriculture across North America. The highest value agriculture—nut and fruit trees—will consolidate in California, commodity grains will grow in the flat Midwest, and labor-intensive produce will be grown more often in Mexico. There, agriculture and individuals may clash over water. For decades, the Yaqui people of Sonora in west Mexico have been fighting to preserve their rights to the region’s precious water. As domestic wells run dry, water trucks have become an increasingly common sight in Mexican cities.

All told, these water wars suggest that like coffee, tomatoes could increasingly become a luxury item.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Tucson, Ariz.

Tucson, Ariz.

Nogales, Ariz.

Las Vegas, Nev.

Death Valley

Sequoia National Forest

Hanford, Calif.

Denair, Calif.

Tulare, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Sheridan, Ore.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.