“We Just Keep Trying to Beat Every Show With the Funny Stick Until It’s Funny”

A conversation with Dan Povenmire and Swampy Marsh as Phineas and Ferb approaches the final day of summer.

Photo by Valerie Macon courtesy Disney XD

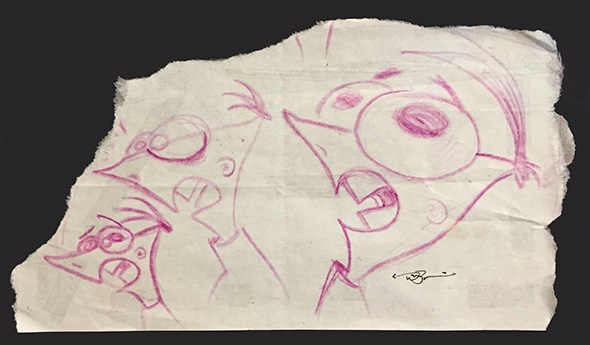

One night in a Pasadena restaurant in the mid-’90s, the animator Dan Povenmire—then working as a writer on the Nickelodeon series Rocko’s Modern Life—doodled a simple cartoon on the butcher paper covering his table: a triangle-headed boy with a pair of round bubble eyes and a mouth agape in nervous alarm. It’s an expression that’s hard to imagine on the wedge-shaped face of Phineas Flynn, the unflappably cheerful young inventor that triangle-headed kid would become—but mouth shape aside, the character is pretty much fully present in that first sketch. As Povenmire would recall when Phineas and Ferb finally had its premiere on the Disney Channel nearly 16 years later, “I tore that piece off and told my wife, ‘This is the show I'm going to sell.’ ”

Well, eventually, anyway. Along with his co-writer on Rocko’s, Jeff Marsh, Povenmire imagined that triangle-headed kid into an elaborate and conceptually bizarre fictional universe—one whose complexity they refused to relinquish when executives suggested they eliminate some of the multiple ongoing plot lines.

After early attempts to pitch their show failed, the men’s professional paths separated for a time—Marsh moved to England to work on two animated shows there, while Povenmire became part of the production team for Fox’s Family Guy, where he always made sure to keep a Phineas and Ferb portfolio on hand in case the chance for an impromptu pitch meeting arose. It wouldn’t be until 13 years later, after repeated attempts to sell the idea to various networks, that Povenmire was able to convince Disney to let them shoot an 11-minute pilot, with the possibility of getting picked up for a 26-episode season. Marsh describes getting a phone call from Povenmire in England: “ ‘Do you want to work on Phineas and Ferb?’ The next sound he heard was me packing.”

Drawing by Dan Povenmire courtesy Disney XD

Soon after I began watching Phineas and Ferb with my daughter—as I remember, it was this joke and this song that first drew me in—I wondered, Who in God’s name are the minds behind all this madness? Now that Phineas and Ferb is about to come to an end (at least as an ongoing weekly series—there’s been talk of a theatrical film, and a spinoff special, The O.W.C.A. Files, is set to air in the fall), I decided to corner Dan and Swampy (a nickname Jeff Marsh was given in England as a play on his last name, and which he now prefers to go by) and ask them a few of the questions that have been piling up in my mind as I’ve spiraled deeper and deeper into the demented yet gentle alternate reality they’ve created – a reality you can revisit this week as Disney XD runs a marathon of every Phineas and Ferb episode, leading up to the series finale, “Last Day of Summer,” on June 12.

It’s a mysterious world of mute animal secret agents and unexplained floating baby heads, where two elementary-school–age half brothers can build a portal to Mars or a space-time–bending trebuchet in their backyard; a suburban dad can become a one-hit wonder to impress his wife (who has a secret past as a pop star); an incompetent archvillain can openly confess his abiding affection for his silent monotreme nemesis; and a cranky teenager can have her face carved into Mount Rushmore, just for the length of a summer’s day.

* * *

Dan Povenmire: So I’m Dan. I’m the one with the low, manly voice.

Swampy Marsh: And I’m Swampy. I’ve got the high-pitched, girly voice.

The first question is from my 9-year-old daughter: Did you draw a lot as children, and what did you like to draw as kids?

Povenmire: You know, I drew when I was very, very young. My mom kept stuff I drew when I was 2 and a half years old, because it looked like, you know, like a jaguar as opposed to a cheetah. Like, it’s very obvious what they’re supposed to be.

Marsh: I don’t know the difference between a jaguar and a cheetah.

Povenmire: They look like they were drawn by a child, but they look like they were drawn by a 12-year-old child or something like that. And I was 2. I couldn’t even speak yet. So, you know, my mom kept that stuff. And I was drawing professionally by the time I was 12. I used to do very detailed sort of photorealistic pen-and-ink work, and I burned out on it around, like, high school. And cartooning really got me back into drawing. I answered an ad, for a campus cartoonist at the university I was in, my freshman year. I was like, Oh, I can draw, and I’m sort of a funny guy. I should try this. Then they paid me to do a comic strip for the paper.

Swampy, I know you had a different trajectory professionally.

Marsh: I was in marketing, computer marketing. I started drawing in first grade. Because the kid next to me was drawing, and I remember thinking: I want to be able to do that! And so I just always drew. But never took that as a career path. I ended up in the computer business, and found myself as the vice president of sales and marketing for a computer accessories company.

Povenmire: And then he decided computers are never going anywhere. Want to get out of that before it tanks.

Marsh: Sailed on that when I was 28. And ended up, thanks to some friends, getting a job on The Simpsons drawing backgrounds.

Was it sort of a dark night of the soul for you? Were you like, I can’t do this anymore, I’ve got to find a creative outlet?

Marsh: I had this horrible moment at the end of a very successful day, where I realized I just felt nothing about it and I didn’t care. And I had that fear that I would, because I was successful at it, that I would be there 20, 30 years down the road, doing this job and just not caring about what I did. And that was this horrible, frightening thing.

I’m particularly interested in your partnership as creators.

Povenmire: Is this the Why are you two not sick of each other? question?

Exactly.

Povenmire: Our answer to that question is: What makes you think we’re not sick of each other?

Marsh: I have blinders on most of the time, so I can pretend he’s somebody else.

Povenmire: You know, Swampy and I live as far away from each other as we possibly can and still work together. He lives in Venice, and I live in the other end of Pasadena, and, you know, we meet in the middle. So we don’t really get that much of a chance to get sick of each other, because we see each other at work but we’re not always together at work. We’re doing different things on the show and stuff. But we just always felt like we were funnier when we were in the room together than we are when we’re separate.

Marsh: We have so many different artistic, comedic, musical sensibilities that are the same, it makes so much of what we do incredibly easy. And if you couple that with—for some reason we have the ability to be brutally honest with each other about what we’re doing without it being offensive.

Povenmire: Well, I think that’s because we both have really huge egos.

Marsh: Yeah.

Povenmire: But very healthy egos. So we’re always sure that we’re right. So, you know, somebody else challenging that doesn’t piss us off.

It sounds like you don’t get into too many creative battles with each other. Are there episodes you’ve strongly disagreed on?

Povenmire: I think there was, like, it was how many times Perry the Platypus would punch Doofenshmirtz in the face in the first Shrinkinator episode.

Marsh: Yeah. That was our biggest disagreement.

Povenmire: I was like, “I want him to punch him a bunch of times,” and he felt like it was too brutal. And I was like, “Yeah, but it’s funny!” And he was like, “I don’t want my kid to punch people in the face five times!”

Marsh: Three is fine.

Thanks to your informative rap video “Animatin’ ”, I now know that you draw the storyboards for each episode at the same time you write the scripts, and that many weekly animated shows don’t do it that way. Can you talk about why that choice works better for you and what you think it brings to the show?

Povenmire: Well, that’s how we did Rocko. That’s how they did Ren & Stimpy. That’s …

Marsh: … how they did the original Disney cartoons, and Warner Bros.

Povenmire: Yeah. To me, if you want a lot of visual humor, the way to do it is have visual people do it. We really needed to do that on Phineas, because two of the main characters don’t speak. So, you know, like Ferb and Perry would have just disappeared in scripts. It would be hard for us to even get Disney on board with the show if we hadn’t shown them a storyboard first. They wouldn’t have gotten the charm if they hadn’t seen it.

I’ve heard you say that you don’t conceive of Phineas and Ferb primarily as a show for children—that you started creating it mainly to make each other laugh. Both of you have become parents since you first thought up the show in 1993, and have lived through a period in your lives of simultaneously creating entertainment for kids (or at least, airing on a channel designed for them) and raising kids. I wonder how that overlap has changed you, as both creators of children’s entertainment and as parents?

Povenmire: Well, Swampy was already a parent by the time we sold the show. And I was a parent by the time we really started working on the show. My daughter was born, like, the same month that the show got picked up. When we got together to really start writing episodes of this show, which had been in our brains for years, we made a very definite decision to make it kinder and gentler. Could we make a show that was funny and edgy without anybody, you know, being motivated by meanness?

I remember noticing when I started watching it with my daughter, Phineas and Ferb don’t enjoy defying Candace. It’s not something they’re seeking to do.

Povenmire: They’re just trying to have a great day. Candace is just going for fairness. She doesn’t want to hurt them. She feels like, If I did this, I would get in trouble, so it’s only fair that they get in trouble. I think it’s a lot of why the show caught on, because I think parents feel very safe having their kids watch it. And it just has this positive energy about it that I think is really infectious.

Marsh: We never backed off of a joke because we thought it was over the kid’s head. The only things we ever cut were stuff that was inappropriate.

Povenmire: Our rule was: If it makes the parent laugh, and the kid asks why, that can’t be an uncomfortable conversation.

Right. It should be expanding the kid’s world, not taking them into a world you don’t want to take them into.

Povenmire: Exactly.

Was it always clear to you that Dan would perform the voice of Dr. Doofenshmirtz and Swampy would be Major Monogram? Did you experiment with different voices to see what fit, or try other voice actors out in these roles before deciding to do them yourselves?

Povenmire: We only ever did those voices for them. It wasn’t like we were looking around, trying on different voices. Doof was just the first voice I used when we were first pitching it to the executives. And Swampy always felt like Monogram should sound like his version of …

Marsh: Walter Cronkite.

Povenmire: Walter Cronkite. And apparently the Doof voice has been around for a long time. My sisters laugh, because they say that’s the voice I would use when we were young whenever I was the bad guy in our imaginary games.

Marsh: As we started listening to people who were auditioning for the role, we realized all we were gonna do was try to direct them to do an impression of the voices we were already doing.

Right. Those are some pretty bizarre characters to get into the motivations of, if you didn’t create them.

Povenmire: And Doof just became such a … we did a lot of writing for Doof where I would just start talking like Doof, because he has certain speech patterns, and he tends to start into the next sentence before he’s even sure of what he’s saying, so you get all of the stammering, where he’s, you know, [Doof voice] “The next step is … ” before he really even knows what he’s gonna say.

Marsh: The other problem with other people doing it is that you get folks that are incredible voiceover talent who can give you an exact German or Hungarian or whatever it is. And Doofenshmirtz I think is funnier, because he’s …

Povenmire: Vaguely Eastern European.

Marsh: Yeah, nebulously Eastern European.

Povenmire: He rolls his Rs.

Marsh: That makes him funny.

Courtesy Disney XD

Structurally speaking, Phineas and Ferb is the most “formulaic” show I can think of: Sometime in every 11-minute episode, with the regularity of the cosmic spheres, Phineas and Ferb must build something awesome, Candace must try and fail to bust them, Doofenshmirtz must build and then be foiled by an ill-conceived ’inator, Perry must find a cool new way to vanish into Monogram’s lair, etc. And yet within the rigidity of that format, you find so much freedom—and the show itself is all about turning ordinary life into a space of freedom and curiosity. When you came up with the idea that the show would always adhere to this very strict format, did you have any sense of why that was so important to the show? Were there other cartoons—or works of art of any kind—you were influenced by in making this choice?

Povenmire: The reason we wanted to do several stories at once is Rocky & Bullwinkle, because that was what we grew up with. But they did it as an anthology, where they’d check in on one story and come back. The formula really came from Snuffleupagus on Sesame Street, and how Big Bird had this big, furry, mastodon-type character that only he would see, and then he would, like, go to try to find other people to get them to bring them back and show them the Snuffleupagus, and then the Snuffleupagus would always …

Oh, right! And that became Candace. That’s great.

Povenmire: Exactly. So that’s Candace and Mom in a nutshell. And then when I had kids and I saw Sesame Street again, Big Bird is there with Snuffleupagus and all the people! And they can see Snuffleupagus! Somewhere in between my childhood and their childhood, he actually got to show people Snuffleupagus for the first time, and I missed it.

There was a metaphysical shift in the Sesame Street world when you weren’t looking.

Povenmire: Yes.

What are your favorite episodes?

Povenmire: Ooh! I have several episodes that I think turned out almost as good as I wanted them to turn out. Most of them are a bitter disappointment when I watch them, because I know all the stuff that I wasn’t able to fix. But I love “The Fast and the Phineas,” the racecar one. I love “That Sinking Feeling,” the Love Boat episode. To me, maybe the best thing we’ve ever done is the second half of “Summer Belongs to You,” which was the big hour-long special.

Is that the one where they go around the world?

Povenmire: Exactly.

That’s a great one.

Povenmire: I think that the last 11 minutes of “Summer Belongs to You” is maybe my favorite thing I’ve ever done. I think it’s so good.

Marsh: It was so nice doing the first pilot episode, “The Rollercoaster.”

Povenmire: Yeah.

Marsh: We hadn’t worked together in 13 years. So that one has, you know, it’s a sentimental favorite. But I still go back to how much I enjoy “Gettin' the Band Back Together.” It was the first time that we let Phineas and Candace—

Povenmire: Work together on something.

Marsh: Work together, and they have this very small moment, a fist bump. And it really lets you know that they love each other.

Povenmire: And they do something wonderful for Mom and Dad. It’s really romantic for their parents. And they’re not grossed out by it.

Marsh: No “eww!”

Povenmire: It’s a really sweet, sweet episode. And it was the first one that was really a musical, where we sort of furthered the plot with music with no discernible source, you know. Before that we would always do it as Oh, it’s a soundtrack song, or maybe Phineas and the gang are playing it on instruments or something.

Photo by Valerie Macon courtesy Disney XD

You guys write the songs together, the words and tune, and then you give them to somebody to orchestrate?

Povenmire: Yeah. We grab guitars, and it’s usually Swampy and me and some other people—Martin Olson and sometimes Rob Hughes. There are several people who are musicians here. And we would get together, you know, like on Friday night with guitars, and knock a song out in about an hour, and then we would demo it on GarageBand and send it to our composer.

Marsh: In the early days, we would sing it onto his answering machine.

Povenmire: The guy who does all the incidental music, all the orchestrations and the score.

Marsh: He still has all those recordings.

Povenmire: He produces all those songs. It’s almost all him playing.

A comprehensive list of the tooniest tunes in the show's four-season run.

Is that Danny Jacob?

Povenmire: He’s a genius. And that’s the best thing, because I was in a band for years, where we’d write the song and then we would spend, like, two whole days recording all the different pieces and miking the drums, and it was so much work getting the recording done. And then for the show we’d come here, we’d write a song, we’d send it to Danny, and he did all the hard work.

Marsh: We used to be able to send it on Friday, and literally by like Monday or Tuesday, we’d have some semblance of a demo track. Not the final piece, but something that sounded like a professional demo. Like, cool!

Is he the one who wrote the “hard work” music? That’s the best. [Hums it to demonstrate]

Povenmire: The quirky-worky song!

How did the two of you come to decide it was time to end Phineas and Ferb? Was it a hard decision?

Povenmire: We’d gotten through these four seasons, and then they wanted to do all these hour-long specials. They felt like they were getting more bang for their buck with the hour-long specials. And it was like, well, if we’re gonna do hour-long specials, I don’t know that they’ll necessarily want to go back and do a series after that. So if we’re doing the hour-long specials, one of them should be, you know, the finale. Let’s do that and just say, OK, we’ll do it in such a way that if you want to at any point in the future, you can make more. But let’s end it at the last day of summer. It’s been going on for 126 half-hours, and we said there were only 104 days of summer to begin with, and most of the half-hours have two days of summer in them.

Marsh: And it sounds cliché, but, you know, you go out before you’ve gotten to the point where you think, Oh my God …

I’ve often wondered how you maintain the level of fun and joy that you seem to in making this show, while the incredible logistical work has to be done to put out an animated show every week.

Marsh: Because cartooning is such laborious, dull factory work. [laughs] No, we’re very lucky to work in this kind of a job, where you’ve got a bunch of creative people coming together every day, and hopefully we’ve created an environment where everybody contributes and everybody feels like they can say crazy weird funny stuff. So we spend a good portion of our day laughing and giggling and being silly and playing music. It’s hard not to continue to be enthusiastic about what you do.

Povenmire: You know, we also know that we could be digging ditches or working in an office, you know, pushing numbers and stuff like that. So I think we’re very thankful for what it is we get to do for a living, and I think that keeps us, you know, on the positive side. Any job ends up with stress, and certainly there’s always a deadline looming when you work in TV. It’s sort of constant. We just keep trying to beat every show with the funny stick until it’s funny, and try to make sure that it’s funny when it goes out the door.

There was a moment most of the way through the first season where I was in the editing room, and some joke was not working, and usually I’m like that last line of defense right before it goes out the door, and I can usually come up with something that will work for that instance. I was just tired. And this joke wasn’t working. I was like, I don’t know what to do with this. I have no, there’s nothing in my brain. It’s like I’m completely used up. Oh my God, what am I gonna do?

And then suddenly I thought, Wait a minute! There’s like four people down the hall who Disney is paying to be funny for us! And I called them, I said, “OK, here’s the joke that I don’t have anything for.” They threw out, like, five different jokes. I picked one, I put it in. And we moved on. It was so liberating! After that, if I was stuck for 15 seconds, I would just call the writers and have them come down.

Marsh: At any given moment, we’re no more than 30 or 40 feet away from 30 or 40 of the most creative people we know. And that’s great.

My last question: there’s a live-action tag you guys made, I think it’s at the end of “Act Your Age,” where Swampy is weeping, saying, “They’re growing up so fast!” and Dan is saying, “I have things to do, I gotta go.” And I’m wondering, is one of you more that way now than the other?

Povenmire: We’re both pretty easy cries.

Marsh: Oh, we are. It’s really sad.

Povenmire: We’ve had a lot of great stuff happen because of the show, and almost all of it makes us cry. You know, the first time we saw the character walkarounds at Disney parks, we got teary, and the first time we saw the thing at Epcot … there’s all these firsts, and then there were all these lasts. You know, the last time we recorded all the kids, the last time we recorded Vincent [Martella, voice of Phineas] and Alyson [Stoner, voice of Isabella] and Ashley [Tisdale, voice of Candace] …

Because you don’t usually tape your vocal parts in the same place, right?

Povenmire: Exactly. And then, you know, the end of an animated show is like a long, slow degenerative illness. If you’re on a sitcom and it has a finale, everybody’s there for the finale, somebody calls “wrap,” and you all go have a party.

Marsh: It’s all nice and neatly …

Povenmire: But it takes like 10 months to do an episode of animation, and, you know, the writers’ team leaves, then the storyboard guys start to trickle out—there’s six months of people leaving, and then there’s a few months of just waiting around for the animation to be finished. So you go from a staff of like 70 people, this bustling activity, to, you know, to …

Marsh: Crickets.

Povenmire: I think the last crew photo we took, there were seven people in it.

Povenmire: Yeah. That was what it was like for almost a year. We had sort of come to terms with the show ending. And then when they announced that the show was ending, which was only a couple weeks ago, I was waiting outside a courtroom to go in for jury duty. They were holding us out in the halls, and I saw that [Disney] had announced it, so I tweeted it, because I couldn’t tweet it before then. And immediately, there were like hundreds of really emotional tweets from people. Because for them, it was all brand-new that it was ending.

Right. So it’s a second wave of mourning that you have to go through.

Povenmire: I started reading them, and some of them were really emotional! And suddenly it became new to me again, and I started crying in the hallway. I went into the bathroom to splash water on my face. When I looked at my face, I was like, “I look like a crazy person!”

Marsh: That should get you out of jury duty.

Povenmire: I called him up at work, like, “Swampy, are you crying?” He said, “Yes. I’m crying.” It’s, you know, it’s been a great thing. It’s been a huge thing in our lives, and the kids themselves, the animated kids, these guys that we created, we feel like they’re our children. So it’s very sad, it’s bittersweet to say goodbye to them. But I feel like we’ve done a good job.