“A Robot Has Shot Its Master”

The 1930s hysteria about machines taking jobs and killing people.

In the autumn of 1932, a British inventor named Harry May invited some friends over to see a demonstration of his latest invention, a robot called Alpha that could fire a gun at a target. Operated by wireless control, the robot sat lifeless in a chair on one side of the room. May placed a firearm in the robot’s hand and made his way to the other side of the room to set up a target. With the inventor’s back turned, the two-ton Alpha slowly rose to his feet and pointed the gun with his metallic arm. The men shouted warnings while the women screamed in terror. The inventor turned and was startled to see that his robot had come to life—and was now pointing a gun directly at him. Alpha lunged forward.

At the last possible moment, the inventor put his hand in front of his face to defend himself. The gun went off, the sound of discharged bullet echoing in the room. In that moment, Alpha became the first robot to rise up against his inventor. The story made headlines in newspapers across the United States, relayed as fact for the most part. Many of the stories quoted the inventor as saying, “I always had the feeling that he would turn on me some day.” A small-town newspaper in Louisiana ran an editorial in the Sept. 27, 1932, issue titled “Our Dread of Robots.” It recounted the story of Harry May’s mechanical man come to life and compared it to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: “[L]ife has imitated art once more. A robot has shot its master.”

None of this, of course, actually happened. At least not in the way that most everyone in 1932 would seem to believe. Harry May had indeed wanted to show off his robot firing a gun. But in reality, the firearm accidentally discharged as he was placing it in the robot’s hand. Mr. May was not shot; he suffered only a minor burn on his hand from the discharge, as gunpowder is wont to do.

But why were people so willing to believe that a robot had blinked alive and decided to turn on its master? What about the 1930s lent itself to a fear of technology that was made tangible through a humanoid robot? Predictions for the future are always a direct reflection of the times in which they’re created. During times of economic insecurity it’s hard not to be filled with anxiety about the future of your country, your family, or your employer—should you be so lucky as to be employed. Just as all politics is local, all futurism is now. Over the last few years we’ve seen Americans of all political persuasions flood the streets; concerned about the future, and more often than not, concerned about their jobs. At the same time, we’ve seen a renewed fear of robots invading the workplace. Earlier this fall, Slate’s Farhad Manjoo warned that even the highly educated—doctors, lawyers, scientists—could find their jobs outsourced to robots in the future; farm workers and warehouse employees are in more immediate danger of being replaced.

The Great Depression, like today, was quite obviously a dark time for the American worker. The unemployment rate hit nearly 25 percent by 1933, leaving 13 million people out of work. And people needed something to point to as the source of their woes. Rightly or wrongly, a great many things took the blame: the president, the weather, immigrants, the wealthy. But with the tremendous rush of technological advancement that was seen in the 1920s, there was a new and terrifying thing at which to point our unemployed fingers: the robot. Coined in 1921, the word robot was still relatively fresh to the national lexicon. But it was a great shorthand for something frightfully inhuman or dehumanizing.

And Frankenstein was the best way to illustrate this fear. Like the Louisiana editors, Bruce Catton invoked Shelley’s frightening tale in an editorial that appeared in the Sept. 28, 1932, Sandusky Star Journal of Sandusky, Ohio. Catton went on to explain:

A psychologist could probably make a good deal of this fascinating dread of ours for mechanical monsters. Machinery has created a revolution in our life. The wage-earner, the farmer, the soldier, the merchant, the politicians, the schoolmaster, the printer—all of us, in every moment of our lives, live differently than our ancestors lived because of the constant increase in the mechanizaton of society.

Many feared that fewer workers in factories—factories that were replacing manpower with more machines—meant the utter collapse of an already depressed economy. Certain industries were seen as being at particularly high risk of a robot invasion. In 1930 the American Federation of Musicians spent more than $500,000 to fight the advance of “robot music”—prerecordings on records—with the Music Defense League. They ran a series of ads in newspapers across the United States and Canada that featured illustrations of robots. These menacing mechanical men represented the dreadful threat of recorded music that was seen as putting musicians out of work. Joseph N. Weber, president of the American Federation of Musicians, said in the March 1931 issue of Modern Mechanix,

The time is coming fast when the only living thing around a motion picture house will be the person who sells you your ticket. Everything else will be mechanical. Canned drama, canned music, canned vaudeville. We think the public will tire of mechanical music and will want the real thing. We are not against scientific development of any kind, but it must not come at the expense of art. We are not opposing industrial progress. We are not even opposing mechanical music except where it is used as a profiteering instrument for artistic debasement.

The campaign to keep “real” music and “real” art in theaters was vicious. The robot represented everything that was artificial and threatening to the establishment of musicians who played live music. The campaign called out for the public to join in the fight. They were to save the art of music from “debasement.”

An advertisement in the June 5, 1930, Bradford Era of Bradford, Pa., decried the Hollywood movie machine that an established industry is now trying to protect: “300 musicians in Hollywood supply all the ‘music’ offered in thousands of theatres. Can such a tiny reservoir of talent nurture artistic progress?” The irony, of course, is that today the music industry is battling to protect recorded music. Protectionist policies to save the old business models of newspapers, movies, and recorded music mimic those of history.

This is not to say that there weren’t techno-utopian visions of the future during this period. Nor were all predictions about robots negative. It just happened that those who were able to look past the Great Depression and see a glorious technological future happened to be quite well off. Take, for instance, Walter S. Gifford, president of the American Telephone and Telegraph Co., who disagreed with Weber in the March 1931 Modern Mechanix:

This depression will soon pass and we are about to enter a period of prosperity the likes of which no country has ever seen before. It is inevitable that business through science will work toward a social and industrial Utopia which will be gained by the perfection of the best and cheapest possible service consistent with financial safety.

And then there were the technocrats. The Technocracy movement, which started in New York in 1932, envisioned a society where reason and scientific efficiency vanquished all the world’s problems, including the Depression. The first step in their plan was to replace all politicians with engineers and other scientifically minded professionals. Described as “a revolution without bloodshed,” the Technocrats promised a guaranteed income which they believed would bring an end to crime and disease. One particularly striking issue of the Technocrats’ magazine even featured a cover with a robot, the text reading: “Thirty million out of work in 1933—or $20,000 guaranteed income for every family—which?” Believers in Technocracy’s socialist utopia both feared and respected this new hulking robot of automation that Americans believed were taking away jobs. Technocracy presented a world wherein humanity conquered the robots before the robots could conquer them. Technocracy’s brief heyday came to an end when one of the movement’s founders, Howard Scott, gave a rambling, incoherent, and much-ridiculed speech on national radio on Jan. 13, 1933.

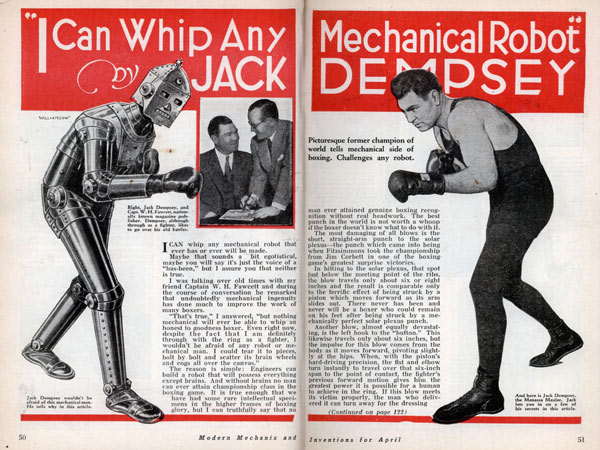

The mythical fight against the mechanical man also made its way to the boxing ring. The April 1934 issue of Modern Mechanix featured an illustrated spread wherein boxing great Jack Dempsey goes toe-to-toe with a foreboding robotic opponent wearing boxing gloves. “I Can Whip Any Mechanical Robot” the headline screams. In the piece, a confident Dempsey proclaims, “I wouldn’t be afraid of any robot or mechanical man. I could tear it to pieces, bolt by bolt and scatter its brain wheels and cogs all over the canvas.” Even Mickey Mouse got in on the action in 1933, with the release of the short animated film Mickey’s “Mechanical Man.” The film shows Mickey the inventor concocting a robot to fight against a gorilla—who subsequently pummels the robot. Everything old truly is new again: Just this year, Dreamworks released the robot-boxing film Real Steel, which Slate’s Forrest Wickman called a celebration of “the supreme might of man and machine working in unison, a combination that ultimately wins out over the soulless tech geekery which aims to outmode workers altogether.”*

Just as the 1930s worried about the tremendous upheaval that the “mechanization of society” had brought, so too do the philosophizers and pundits of our age worry about the corrupting influence of the Internet. From the vantage point of 2011 we might laugh at the people of the 1930s, asking ourselves what on earth they were worried about, but it’s always a matter of degree. No doubt cavemen worried about the corrupting influence of the wheel just as many worried that the written word would destroy society by allowing man the luxury of no longer having to memorize complex tales of fact and myth. These technologies—these robots—are extensions of our humanity. The wheel and the book and the Internet either allow us or force us to become cyborgs. Your belief in this as a good or bad thing likely depends on your economic situation at the moment.

Check out a slideshow about the great robot panic of the 1930s in the pages of print media.

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.

Correction, Dec. 1, 2011: Due to an editing error, this article originally misspelled the last name of Slate editorial assistant Forrest Wickman. (Return to the corrected sentence.)