Can This Man Save Pinball?

An arcade entrepreneur has a plan to resuscitate the dying pastime—with a little help from the Wizard of Oz.

Mariana Juliano for Slate.

The last guys who tried to save pinball bet all their quarters on a bunch of 3-D aliens. With sales of new machines dwindling in the late 1990s, the top execs at Williams, the company that controlled 80 percent of the worldwide market, called on their designers to reinvent the game. They emerged with an arcade centaur—the head of a video game on the body of a pinball machine—in which pixelated, holographic-looking Martians marauded among the mechanical gewgaws. “Pinball 2000” was a technological marvel. It also nearly killed pinball forever.

In October 1999, not long after Williams introduced Pinball 2000 in a promotional video featuring clips of the moon landing and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, the company shuttered its pinball division. As the excellent documentary Tilt: The Battle to Save Pinball explains, Revenge From Mars, the initial Pinball 2000 title, sold well, but a Star Wars Episode I-themed follow-up got less traction with the Jar Jar-hating masses. Rather than prop up its declining pinball operation, Williams chose to focus on a more promising line of business: slot machines.

Thirteen years after this failed holographic experiment, pinball is just barely alive. A single company, Stern Pinball, holds a virtual monopoly on new equipment. What was once a quintessential American pastime has been exiled from its natural habitats—bars, diners, and even arcades.

For Jack Guarnieri, pinball’s decline brought on an existential crisis. Guarnieri has held most every job that has to do with flippers: repairman, game operator, reseller, inventor. With his livelihood and life’s passion in peril, he figured there was only one thing to do: Create history’s greatest pinball machine, one that would introduce a new generation to the pleasures of a well-struck ramp shot. Three-dimensional aliens couldn’t save pinball. Can a small-business man in New Jersey?

******

Mariana Juliano for Slate.

In the Jersey Jack Pinball factory, history is covered in bubble wrap. A handful of simple, gorgeously illustrated 1960s-era games—Flipper Clown, King of Diamonds, Road Race—stand in a back corner, ready to ship to a nostalgia-minded connoisseur. The rest of this workshop in Lakewood, N.J., has been given over to a brand-new game with an old-timey theme, the machine Guarnieri believes will rocket pinball into its next golden age: the Wizard of Oz.

Each Oz pinball machine is the size of a casket built for a member of the Lollipop Guild. On this day in early fall, millions of dollars of parts—LED lights and emerald-green legs and a forest’s worth of anthropomorphic plastic trees—are sitting in cardboard boxes, waiting to be fished out by arcade-world craftsmen. On one assembly line, they’ll put together the machine’s heart, adding rails, rollover buttons, and magnets to the yellow-brick-road-laden playfield. They’ll also add the brains, stuffing the PC board, power supply, and other electronics inside the Wizard of Oz’s exterior shell.

In addition to the parts and labor, building a new pinball company takes courage, plus a light messianic streak. The 55-year-old Guarnieri, who’s got a lot of his native Brooklyn in his tireless voice, is the best kind of salesman. He talks fast but means everything he says, remembers every detail of anything that has to do with arcades, and doesn’t take himself too seriously—while still treating the quest for pinball supremacy as a noble, essential mission.

In Guarnieri’s view, this humming factory is proof of all you can accomplish when you love what you do. Bean-counter types have “said some shitty things” about his arcade ambitions, he says, telling him he’s crazy to throw his money into the shrinking ball-and-flipper market. Perhaps it’s true that irrational exuberance can lead you to bankruptcy. But it’s also the only way to make something great from absolutely nothing, just as Guarnieri’s role models did. “What overcomes doubt,” he says, “is the resolve and the passion and determination of people like Steve Jobs and Sam Walton, whether it’s going over the hill in Normandy or whether it’s building a freaking pinball machine.”

Pinball first captivated the spare-change-having masses during the otherwise unamusing Great Depression, then surged again after World War II with the game-changing advent of the flipper. The pinball wizardry chronicled in the Who’s Tommy launched a silver-ball renaissance in 1969, and the development of bell-and-whistle-larded computerized machines in the 1970s kept those balls rolling. New York City also ended its three-decade-plus pinball ban in 1976—Mayor Fiorello La Guardia had believed it was “a racket dominated by interests heavily tainted with criminality" that pilfered from the "pockets of schoolchildren in the form of nickels and dimes given them as lunch money”—further clearing the way for the game’s cultural ascension.

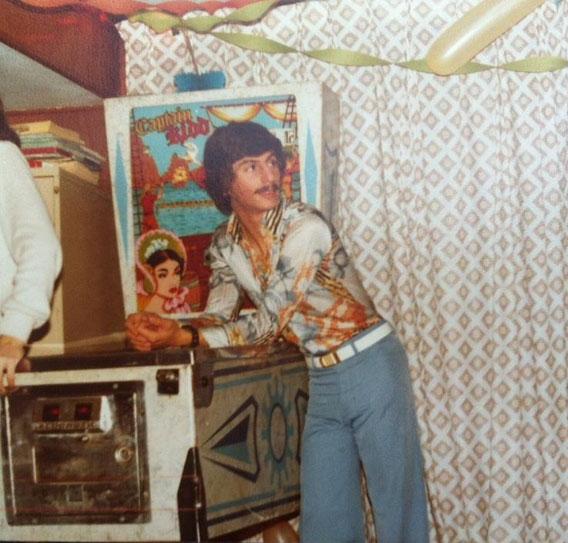

It was right around that time that Guarnieri got into the business, taking a job as a pinball mechanic after graduating from high school in Brooklyn in the mid-1970s. Soon after, Pac-Man came along and chomped up all the coins. In 1979, pinball manufacturers sold more than 200,000 machines in the United States; three years later, they sold 33,000. During that same period, video games went from collecting around $1 billion per year in quarters to a high of $8 billion, with 1980’s Pac-Man reportedly earning more than $1 billion in coins in its first year on the street.

Photo courtesy Jack Guarnieri.

As silver balls lost their capacity to thrill in the 1980s, Guarnieri rode the video game wave. At his peak as an arcade operator and service person, he oversaw 400 video games in and around New York City, in pizzerias and hardware stores and barber shops, as well as the Waldorf-Astoria and the World Trade Center’s Skydive Restaurant. For a time, Guarnieri says, the joystick tycoon’s biggest concern was excessive profitability—once in a while, a massively popular game like Asteroids would jam up with quarters, rendering it inoperable.

But around 1986, the arcade bubble burst. And though pinball had a brief resurgence a few years later—1992’s The Addams Family, the game I played obsessively in my college rec center, sold more than 20,000 units, making it the most-popular machine since the 1930s—that market collapsed again in the mid-1990s, leading the majority of manufacturers to abandon the business for good.

Pinball succumbed to the same forces that killed the video arcade. In the 1970s, arcade games far outclassed the entertainment competition, which consisted primarily of three channels of crappy network television, staring contests, and throwing rocks at cars. But with the spread of home consoles and cable TV (and eventually ubiquitous Web access and smartphones), paying to play video games at some retail establishment felt inconvenient and outdated, like carrying a boombox on your shoulder or using an outhouse.

Pinball in particular became a relic from a pre-modern age. Compared with simple video games, which require little maintenance, pinball machines are loaded with mechanical parts that inevitably break down. Video games also generally take up less space than bulky pinball cabinets, and the advent of multi-joystick (and multi-steering-wheel) play allowed operators to earn more than they ever could from a one-player-at-a-time, flipper-based machine. As pinball lost its cachet, then, arcade owners happily shoved aside the less profitable, more aggravating machines in favor of reliable revenue generators such as driving games and games involving spine ripping.

With pinball largely banished from public spaces (unless you live in a hipster haven like Portland, Ore.), most of today’s machines end up in the hands of collectors. Chicago’s Stern Pinball—whose website declares it “the only maker of REAL pinball games on the planet!!”—produces three new titles each year, with recent games including Transformers, AC/DC, X-Men, and Avengers. According to company president Gary Stern, his firm sold more than 5,000 games in 2012. Though Stern says business was up last year, those numbers are bracing—that means an entire year’s run of today’s machines adds up to 25 percent of the sales of a blockbuster like The Addams Family.

A few years ago, Guarnieri—who had started selling new and refurbished pinball machines online in 1999—decided that this direct-to-man-cave fare had gotten stale. At his high water mark, Guarnieri had sold around 1,000 machines annually through his online store PinballSales.com. In 2010, Guarnieri sold less than 50, telling the site Pinball News that “there was no product left for him to sell”—that his customers were yawning at Stern’s sparsely adorned, simplistic games. What they longed for, he thought, was something that didn’t exist, a modernized game that would kick-start a long-stagnant industry and return pinball to the world beyond rich dudes’ basements.

In January 2011, Guarnieri got to work building that game.

******

The Jersey Jack factory is not a place where the dreams you dare to dream just come true. Here, the dreams get built by hand, one ruby-slipper-shaped flipper at a time.

Mariana Juliano for Slate.

When you’re creating a pinball machine from scratch, somebody, somewhere has to craft or acquire every mechanism and fixture. Jersey Jack Pinball licenses its flippers from Planetary Pinball Supply, gets its wiring assemblies from a company in New Jersey, and builds its soundboards in partnership with Massachusetts’ Pinnovators. A woodworking firm in Illinois fashions the Wizard of Oz cabinets and playfields, then sends them to another company that adds the game’s specially designed artwork using a $300,000 inkjet printer. Jersey Jack tested more than 10 different playfield finishes, rolling and shooting hundreds of thousands of balls before determining which one worked best. A pinball-crazy sculptor designed the plastic trees and munchkin huts.

In aggregate, these decisions reveal Jersey Jack Pinball’s grand plan: In every way that matters, the Wizard of Oz is a refutation of how modern pinball machines are designed and built. Rather than choose a bro-friendly theme centered on robots and/or guitars, Guarnieri acquired the pinball-ization rights to Dorothy, Toto, et al. Instead of the standard static back-glass art and dot matrix display, Jersey Jack’s machine is topped by a 26-inch widescreen monitor that displays full-color, cinema-grade animations. The game has no conventional, burn-out-able light bulbs—it’s illuminated by RGB LED lights that can generate any hue. And perhaps most significantly, the Wizard of Oz is the first “widebody” game since the mid-1990s. The fatter-than-usual apparatus means there’s room for an oversize load of eye-catching doohickeys: a spinning house, a winged monkey, a melting witch, and a video-displaying crystal ball that Guarnieri sees as his coup de grâce. “When you look into the crystal ball and see a moving image,” he explains, “you say, Holy shit, how much more could you put into this game?”

All of this stuff has something in common: It’s expensive. In comparison with the cost containment that’s characterized the last two decades in pinball manufacturing, Guarnieri has spent money like a Russian oligarch who’s just bought himself an English soccer squad. First, he assembled a team of underemployed pinball-industry stars like designer Joe Balcer and programmer Keith Johnson. Then, Guarnieri gave them the latitude to build whatever they wanted. “I just said, ‘I want you guys to do the best thing you can.’ The danger in that is that it almost never ends and you don’t know what it’s going to cost,” he says. The game’s higher costs have been passed along to collectors and operators. While the cheapest full-size Stern pinball machine will cost you a little less than $5,000, the Wizard of Oz retails for $7,000.

Two years after Jersey Jack Pinball got off the ground, Guarnieri says the Wizard of Oz is almost ready. There are now 15 test machines on location, giving pinball obsessives the chance to ogle and play the long-awaited, still-not-quite-finished game. (A review on the forum Pinside of the game at iPlay America in Freehold, N.J.: “Beautiful pin. Nothing that I've seen in videos online does it justice. The code is bare bones. As long as the game gets programmed well it will be a huge achievement.”) Guarnieri, though, is finding out that the last few yellow bricks on the road are the toughest to traverse. He’s still waiting for the circuit boards to be finalized, and the programming isn’t quite done either, meaning the test machines only show “30 percent of what the game is.” Last year, he told the Chicago Reader that the games would be ready by late spring or summer 2012. A few months ago, Guarnieri told me he’d be shipping them in January. Now he says he expects the 1,500 customers who pre-ordered the Wizard of Oz to start getting their machines in mid-March.

Regardless of how many games he sells and when he gets them out the door, Guarnieri has already provided a great service for the pinball world. “I don’t care what the industry is, you need at least two manufacturers,” says pinball designer and writer Roger Sharpe. Sharpe, who worked at Williams during the Pinball 2000 era and whose testimony secured pinball’s legality in New York City, says Guarnieri’s company serves as a heartening proof of concept to other potential pinball start-ups (for instance, this one in the United Kingdom).

Gary Stern doesn’t buy that argument. “We are the only pinball manufacturer in the world,” he says. And though he acknowledges that it “will sound arrogant,” he tells me that “pinball will survive if Stern Pinball continues to make pinball machines in a meaningful volume.”

Despite Stern’s protestations, Pinball News editor Martin Ayub believes the reigning pinball king has been forced to step up his game on account of Jersey Jack. After producing a series of simpler, cheaper-to-produce titles in 2010, Ayub says, Stern has now augmented its lineup with “fuller-featured” premium products at a premium price. In addition to the sub-$5,000 “Pro” model of Stern’s Avengers machine, you can get various premium versions with extra ramps, LED lighting, and limited-edition designs for around $7,500, more than the cost of the Wizard of Oz. (At this week’s Consumer Electronics Show, Stern also showed off smaller machines designed for the home market that will sell for $2,500.)

For his part, Guarnieri believes two pinball companies are better than one: “I hope [Stern sells] a million games and we sell 10 million games,” he says. Even so, he intends to keep pressuring his rival: Jersey Jack’s next licensed game, The Hobbit, is scheduled for 2014, to coincide with the final movie in Peter Jackson’s trilogy. If increased competition breeds superior machines, collectors and nostalgic nerds like me will rejoice. But to make pinball a mainstream pastime, Guarnieri must appeal to two more-skeptical constituencies: kids with dollar bills and game operators who want to separate those kids from their dollar bills. (Yes, dollar bills—while operators can set the price to 50 cents if they want, it’s now typical to spend $1 for a three-ball game.)

Mariana Juliano for Slate.

No amount of entrepreneurial enthusiasm or technological sophistication can change the fact that pinball faces the same problems that instigated its post-’70s tailspin. In the age of Doodle Jump and streaming videos of keyboard-playing cats, entertainment options are plentiful and cheap. And compared with most anything else a bar manager, multiplex owner, or arcade operator might choose to plug into the wall, pinball machines tend to earn less money, require more maintenance, and break down more quickly.

This is one thing Gary Stern and Jack Guarnieri can agree on: Pinball will cease to exist as soon as it stops earning money on location. To demonstrate the challenge of keeping pinball commercially viable in 2013, Guarnieri takes me to iPlay America, a 115,000-square-foot amusement center where he’s contracted to service the games. This is the ultimate Darwinian arcade environment. There’s a go-kart track, a laser-tag arena, a whole bunch of rides, and—in addition to the compulsory fighting and shooting games—skill cranes that dispense iPods and iPads to a lucky few. In the days before the beta version of Wizard of Oz hits the floor, there are just two pinball games on display here: Monopoly and Grand Prix, both Stern titles from the 2000s. Neither one looks like it’s been glanced at, let alone played, since before the go-kart-riding kids were born.

The Wizard of Oz, with its big, bright LCD screen and toy-festooned playfield, will certainly draw more eyeballs than an older pinball machine like Grand Prix. But that’s not all that relevant when you’re battling for the affections of today’s overstimulated, under-flippered youth. “Stern is not our competitor,” Guarnieri says. “Any other game that goes into an amusement center is our competitor.” An entertainment center is “like a kiddie casino—you need to try to draw the players’ attention,” says Josh Sharpe, the son of Roger Sharpe and the CFO of Raw Thrills, the company that produces games like Big Buck Hunter PRO and Guitar Hero Arcade. “The LCD helps draw the attention [among] a group of pinball machines. Whether it’s enough to draw the attention away from the Guitar Hero Arcade machine that has the booming speakers and also has the LCD, time’s going to tell.”

As a longtime game operator, Guarnieri knows pinball’s fate depends on the take in the cash box. In the heyday of arcades, Guarnieri says, a game like Space Invaders would earn back what it cost in as little as a month. Now, according to Josh Sharpe—who in addition to his role as a coin-op exec also serves as the president of the International Flipper Pinball Association—operators are pleased if a coin-op amusement pays for itself in a year. If you want to consider the worst case, Sharpe cites an American Idol karaoke machine that his company developed. The device, which instantly burned a DVD of your performance, was the “slickest thing ever, but it just bombed,” he says. “I know that Jack believes [the Wizard of Oz is] going to work, everyone hopes it’s going to work, but ... we don’t know until we put it on location.”

Guarnieri likes his early returns. The games, he claims, have been attracting the rarest breed of pinball player: the human female. And between Dec. 28 and Jan. 3, the Wizard of Oz machine at iPlay America earned $347—a fraction of what the iPad-dispensing skill cranes brought in but a better haul than video games like Big Buck World and Guitar Hero. (For a $7,000 machine to pay for itself in a year, an operator has to earn $135 a week after splitting the game’s proceeds with the location owner.) As of now, just 100 of the 1,500 Wizard of Oz games he’s sold are destined for retail establishments rather than private homes. But Guarnieri believes if he can deliver this kind of return consistently, there’s a “real place again for pinball machines on commercial locations,” perhaps even at pinball-averse mega-chains like Chuck E. Cheese’s and Dave & Buster’s.

Right now, at the moment when his games must prove their worth in the marketplace, Guarnieri is in the same spot where Pinball 2000’s creators found themselves 13 years ago. In the end, 3-D pinball was probably too gimmicky to become a go-to American amusement. But Pinball 2000 didn’t fail as quickly as it did because those holographic aliens couldn’t attract attention—it was because the money men lost faith in the project.

Mariana Juliano for Slate.

That won’t happen with Jersey Jack Pinball. When I step up to play the Wizard of Oz at Guarnieri’s factory, he stands watch at the side of the machine. Since this isn’t a finished game, there’s no protective glass covering the machine. As I miss shot after shot, Guarnieri loses patience and grabs the ball, rolling over various parts of the playfield so I can listen to the speech calls. (“I don’t like this forest, it’s dark and creepy,” says Dorothy, alarmed.) Finally, the ruby-slipper flipper hits the ball just right. “Oh, look, the monkey just took your ball!” Guarnieri says, as if it’s the first time the primate has ever done such a thing. As soon as the silver ball rolls free, I’ll be off to melt the witch, save Toto, and maybe, if I’m lucky, meet this wonderful wizard that I keep hearing so much about.