Watershed Moment

The death of a Montana dam.

-

CREDIT: Image courtesy the Jack L. Demmons Bonner School Photo Collection.

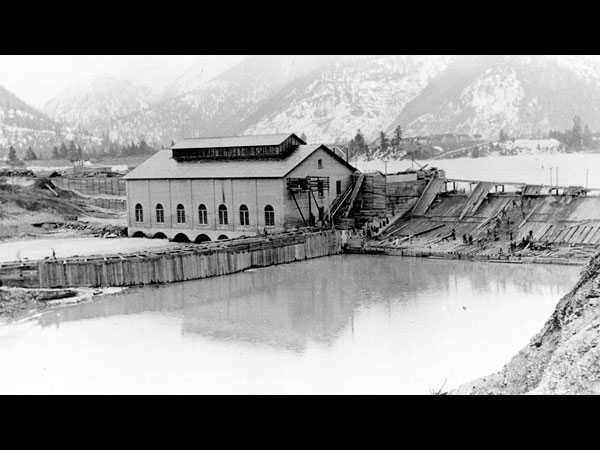

CREDIT: Image courtesy the Jack L. Demmons Bonner School Photo Collection."Clark's Dam," they called it in 1908 (after its owner, U.S. Sen. W.A. Clark), when the generators sent their first spark across the wires. At the public unveiling of the facility, the dam superintendent crowed to journalists and local dignitaries: "No expense was spared in making the dam one of the strongest of its kind—enough power will be generated to furnish the entire western portion of the state with electricity for all purposes."

-

CREDIT: Photograph by Michael Kustudia on a flight by Gary Matson.

CREDIT: Photograph by Michael Kustudia on a flight by Gary Matson.One hundred years on, the dam remains a symbol of western Montana's potential—but now for landscape restoration rather than for industrial imperialism. "Today we are turning the corner," said U.S. Sen. Max Baucus to the people gathered at the confluence to witness the dam breach last month. "We all know Montana is perfect, and today we are making it more perfect." The path to perfection is a muddy one, however. A downstream view taken this month shows the Clark Fork in its temporary bypass channel, the old channel laced with mucky pools, the drained reservoir sediments divided into excavation cells, and the rail cars drawn up to accept their cargo of heavy-metal-steeped sludge. The river breached the dam to the right of the remaining spillway, through the powerhouse gap.

-

Image courtesy the Jack L. Demmons Bonner School Photo Collection.

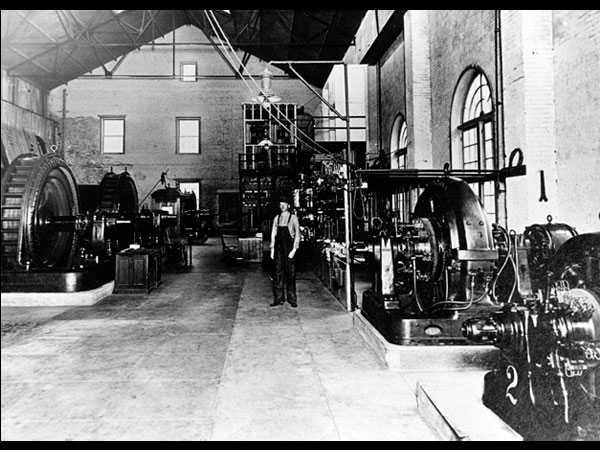

Image courtesy the Jack L. Demmons Bonner School Photo Collection.Of all the recent changes at Milltown, the January demolition of the old powerhouse has perhaps shaken locals most (although in the grand scheme of the cleanup, its removal is but a footnote). Everyone knew that the familiar building, with its oddly elegant windows and its warm brick walls, was destined to go to make way for the river. But that didn't quite prepare people for its absence. The building had become a symbol for the good elements of Milltown's past—honest industry, regional self-reliance, steady work. In this image, a solitary, slightly grubby young man stands in the center of the powerhouse floor. The river flows through turbines lodged in the headwall to the left; they spin the massive generators to produce power. The chair behind the man sits in front of the marble-fronted control panel with which dam operators tracked electricity running through the system and out the lines.

-

Photograph by Caitlin DeSilvey.

Photograph by Caitlin DeSilvey.At peak production in the early years, the dam generated 3,400 kilowatts of power—enough to provide for the local mills and a good portion of Missoula, if not quite all of western Montana. The turbines continued to spin the river's flow into electricity for the rest of the century although the dam contributed a dwindling percentage of total power on the grid. (Montana's largest coal-fired plant today can produce up to 2,094 megawatts.) Montana Power Co., owner of the dam and hydroelectric plant from 1929 until the late 1990s, kept the aging facility going after reservoir contamination was discovered in 1981, partly because that way, it could let the sleeping sediments lie. When deregulation cleared the way for Montana Power to sell off its assets in 1997, regional utility giant NorthWestern Energy acquired the plant (and part of the Superfund liability).

-

Photograph by Caitlin DeSilvey.

Photograph by Caitlin DeSilvey.NorthWestern hired Bill Scarbrough and Mike Haenke (who'd spent their careers working in power plants across the region) to wind down operations and decommission the dam facility. Their work was a kind of industrial hospice care. They threw the switches to silence the generators in April 2006. They offered cups of coffee to hundreds of people who came to pay their last respects. They drained the oil from the equipment, loosened the bolts, and watched the contractors haul the generators and transformers away. The dam's last operators even composed an epitaph for the facility: "Through the thick and the thin, the floods, the ice and the droughts, Milltown Dam Powerhouse has seen it all and survived all but the perpetual march of time. … Alas, the old gives way to the new; so, good and faithful servant, we bid thee farewell." Both men retired on the day of the dam breach in March.

Click here for a sound clip of Scarbrough saying goodbye to the powerhouse.

-

Photograph by Peter Nielsen.

Photograph by Peter Nielsen.It took only a couple of days to demolish the powerhouse. Volunteers salvaged fragments: windows, bricks, the control panel, old signs. Viable timbers from the wood-and-rubble core of the dam's spillway will be set aside. Crushed waste concrete may be used to cover trails in a park at the restored confluence. Contractors will inter other materials elsewhere around the 450-acre cleanup site or, in the case of the contaminated sediments, in an upstream repository near the town of Opportunity, Mont., 90 miles away. Four of the 20-ton generators were sold to other hydro-plants in the region to continue their useful lives. One remains in Milltown, waiting for installation in a future interpretive exhibit. The dam construction gathered together materials from throughout western Montana; the demolition redisperses them.

-

Image courtesy the Jack L. Demmons Bonner School Photo Collection.

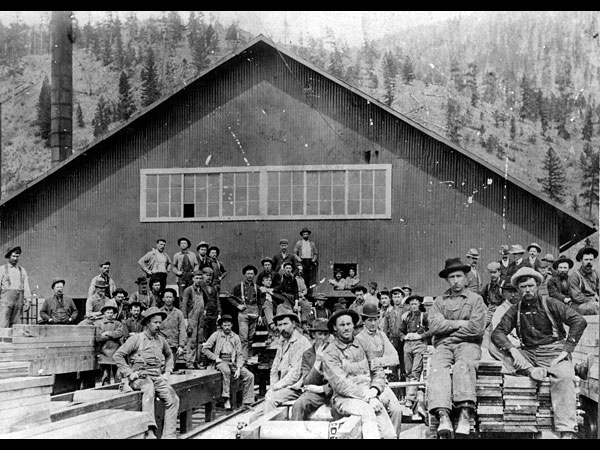

Image courtesy the Jack L. Demmons Bonner School Photo Collection.The dispersion of Milltown's material history is attended by human dispersion. Ten days before the dam breach, owners of the Stimson lumber mill in nearby Bonner, Mont., announced an indefinite shutdown. A mill has operated on this site since 1886; what could well be the last load of logs rolled through the gates on March 21. As an outpost of the Anaconda Copper Mining Co. (the employer of the workers shown here in the early part of the 20th century) until 1972, the mill produced many of the timbers that shored up Butte's mines. No glowing speeches here about making Montana more perfect—just resignation to what everyone could see coming and workers scrambling to find new jobs and new homes.

-

Photograph by Caitlin DeSilvey.

Photograph by Caitlin DeSilvey.Many of the men employed in the Bonner mill over the years spent their evenings in the waters below the dam, fishing. And some of them left their lures tangled on the low-hanging line that stretched from the powerhouse to the far bank. The dam operators collected the lures; a bright row decorated the wall of the powerhouse workshop. Thousands of fish—including endangered bull trout—came up against the barrier of the dam every year in their aborted spawning migrations. Silvery bodies trapped in the hole below the dam sometimes shimmered as a solid mass. The dam offered easy pickings for the fishermen but not such a good deal for the fish. With the breach, these fish will once again spawn in the high, rocky creeks of the upper Clark Fork watershed. The migration has already begun. On April 9, researchers tracked a radio-tagged rainbow trout through the breach channel and up the Blackfoot River.

-

Photograph by Peter Nielsen.

Photograph by Peter Nielsen.The powerhouse is gone, and now a river runs through it once again. The dam spillway will remain for a few more months, and then it, too, will disappear. In a few years, when the mud clears, few traces will remain of the river's electric history. The restored river will produce kayaking waves instead of kilowatts. Houses may sprout in the log yards of the Bonner mill. The name of the place—Milltown—is already an anachronism.

Click here to read a follow-up slide-show essay on the passing of Milltown.