I'm Talking to You, Corded!

The mismatch of technology and picture books.

-

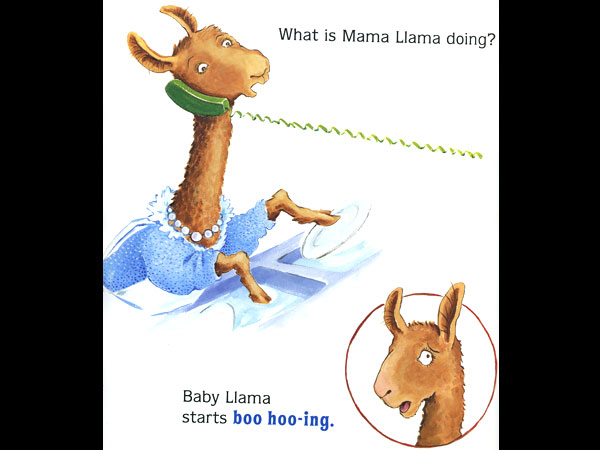

From CREDIT: Llama, Llama, Red Pajama, by Anna Dewdney, © 2005 Anna Dewdney. Used by permission of Penguin Young Readers Group, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. All rights reserved.

From CREDIT: Llama, Llama, Red Pajama, by Anna Dewdney, © 2005 Anna Dewdney. Used by permission of Penguin Young Readers Group, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. All rights reserved.The homes we see in children's picture books—even books published in the current decade and set in the present—often seem conspicuously dated. There are few computers. E-mail is hardly ever mentioned (much less checked). Phones usually have long, loopy cords tethering the receiver to the base.

One example: Anna Dewdney's Llama, Llama, Red Pajama, published in 2005, in which a young llama becomes increasingly agitated post-bedtime while his mother lingers on a telephone call. The emotional tone of the book is timely: Kindly but firmly, Mama demands an end to the "llama drama" and explains to her child that sometimes Mama's needs come first. However, the presence of a corded phone suggests a different era, like the 1970s. The vintage corded phone in another 2005 book, Amy Reichert and Alexandra Boiger's While Mama Had a Quick Little Chat, also looks like it is from the '70s—this time, the 1870s.

This is all kind of sweet: the picture-book world as an old-fashioned oasis from the hustle of modern life. But it's also odd. Would it kill some illustrator to draw a cordless phone? I mean, Anthony Edwards uttered the classic film line, "I'm talking to you, cordless!" to John Cusack in 1985.

Why do modern picture-book scenes often look so dated?

-

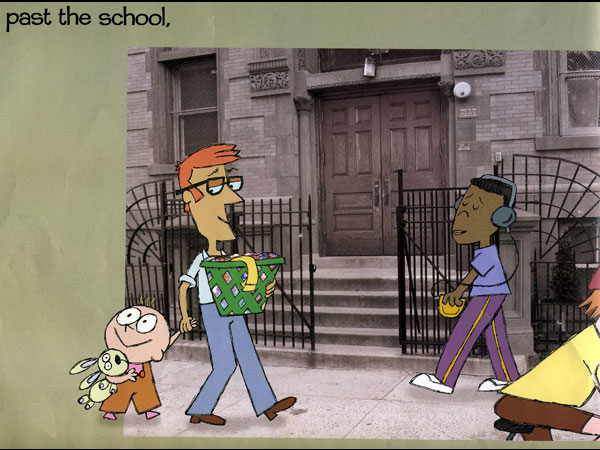

This year, everyone may be listening to music through ear buds, but by 2015, who knows? The iPhone of today may be the car phone of tomorrow.

So by showing a pedestrian grooving to his tunes on giant retro headphones instead of tiny ear buds in his 2004 book, Knuffle Bunny, illustrator Mo Willems can simultaneously conjure up a recognizable image for readers of any age ("Look! That guy is listening to music!") and avoid dating a book with a cultural icon that may or may not be ubiquitous in a decade. (There's also the sly hat tip to the affection that certain hip Brooklynites have for antiquated audio gear.)

-

From CREDIT: What Do People Do All Day?, by Richard Scarry. Text and illustrations © 1968 Richard Scarry. Used with permission.

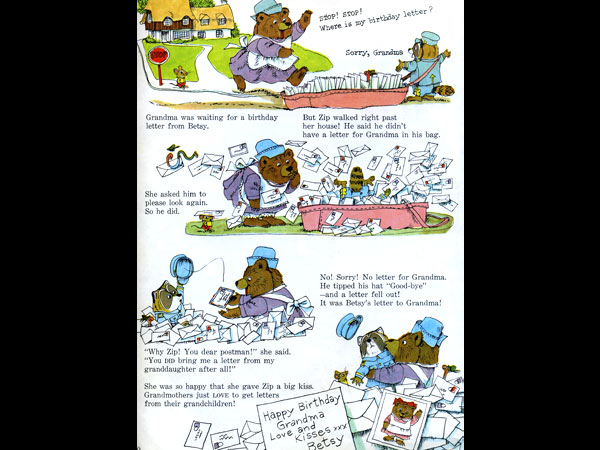

From CREDIT: What Do People Do All Day?, by Richard Scarry. Text and illustrations © 1968 Richard Scarry. Used with permission.Picture-book illustrations explain things to the preliterate set. A book works well if a child can read the visual message without being able to decipher all—heck, any—of the words. Antiquated technology sometimes suits this purpose by clearly demonstrating a linear path of communication. So even though toddlers rarely see corded phones in their own homes, they understand that the curly cord connecting the phones of two characters shows that they are talking to each other. This visual cue is used to good effect in Laura Ljungkvist's 2001 book, Toni's Topsy-Turvy Telephone Day, in which the illustrator's signature unbroken pen line travels from page to page, serving as a phone cord connecting Toni to her many party guests.

Letters and postal carriers accomplish the same thing. In his 1968 book, What Do People Do All Day?, Richard Scarry drew the step-by-step route of a letter from young Betsy through the postal service to her grandmother. Scarry died in 1994, but if he'd been alive to revise the book for its 2005 reissue, I doubt he would have added a show-and-tell story about sending and receiving e-mail. That invisible journey resists the kind of visual explanation provided by Zip, the mailman who rediscovers Betsy's letter in his hat.

-

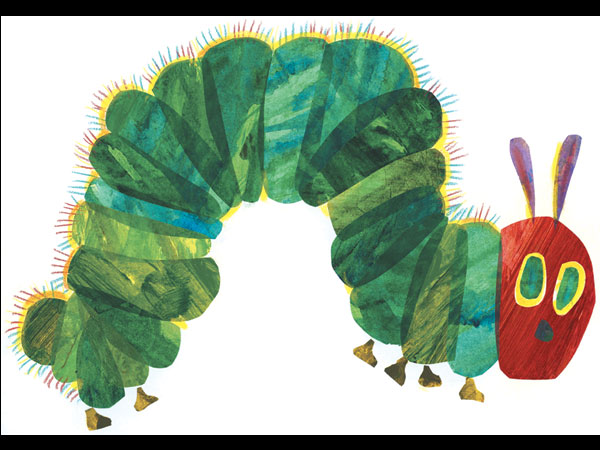

CREDIT: The Very Hungry Caterpillar, by Eric Carle, © 1969 and 1987 Eric Carle. Used with permission.

CREDIT: The Very Hungry Caterpillar, by Eric Carle, © 1969 and 1987 Eric Carle. Used with permission.As a children's book author, I know how much writers and illustrators want their books to endure. When we look for models of longevity in the classic picture books of some modern masters (Maurice Sendak, Leo Lionni, Eric Carle, Margaret Wise Brown, and William Steig), we don't see images of the technology of their day. In fact, look again, and you'll notice that many of these books lack extraneous detail of all kinds. Max's bedroom in Where the Wild Things Are is conspicuously barren. The feast of The Very Hungry Caterpillar is devoured off crisp white pages.

Many of the best picture books are deceptively minimalist in word and image (as you realize when you try to write one). One reason there's little technology is that there's precious little else. In their 1977 book, Simple Pictures Are Best, Nancy Willard and Tomie dePaola tell a cautionary tale of failing to adhere to a minimalist aesthetic. As the subjects of a portrait ignore the photographer's urging to keep it simple and fetch increasingly unnecessary items, the resulting photos go from bad to worse.

-

From CREDIT: Blueberries for Sal by Robert McCloskey, © 1948 Robert McCloskey. Published by Viking, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc. All rights reserved.

From CREDIT: Blueberries for Sal by Robert McCloskey, © 1948 Robert McCloskey. Published by Viking, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc. All rights reserved.Alison Morris, a bookseller and Publisher's Weekly blogger, suggested nostalgia as another reason that modern picture books ward off technology. In an e-mail to me, she observed that picture books often play to the childhood memories of parents, grandparents, librarians, and teachers who, after all, are the ones buying them.

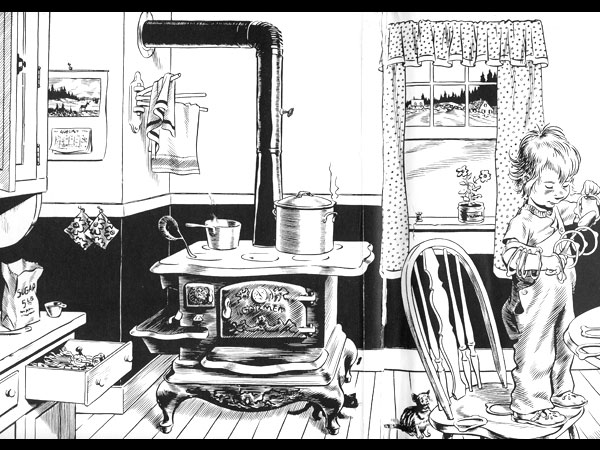

Authors and illustrators also write and draw with an eye to their own childhoods and what they valued in that time. Author and illustrator Marla Frazee cites as an example Robert McCloskey's 1948 book, Blueberries for Sal. In the end pages, McCloskey depicts an old-fashioned kitchen, where mother and daughter can blueberry jam next to a cast-iron stove. Most homes had modern kitchen appliances by the late 1940s. The scene McClosky drew likely re-created one from his own childhood.

-

From CREDIT: Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type by Doreen Cronin. Illustrations © 2000 Betsy Lewin. Published by Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers. All rights reserved.

From CREDIT: Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type by Doreen Cronin. Illustrations © 2000 Betsy Lewin. Published by Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers. All rights reserved.Picture-book creators also wax nostalgic for obsolete objects. Doreen Cronin's ode to a manual typewriter, Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type, won a Caldecott Honor in 2001. Apparently, the book's concept was so clever (and illustrator Betsy Lewin's cows so darned cute) that it didn't matter that the book's intended audience of children would likely have never seen a manual typewriter or heard its "click clack."

Another favorite item in picture books is the film camera. In 2007, the Caldecott Medal went to David Wiesner's Flotsam, a wordless book about a modern boy who goes to the beach and discovers a vintage camera containing film that, when printed, reveals mysterious images. Once again, reviewers championed the unexpected subject matter, and the book found a home with a generation of children who have no frame of reference for cameras that lack image previews.

-

From CREDIT: Penny Lee and Her TV by Glenn McCoy. Text and illustrations © 2002 Glenn McCoy. Reprinted by permission of Hyperion Books for Children. All rights reserved.

From CREDIT: Penny Lee and Her TV by Glenn McCoy. Text and illustrations © 2002 Glenn McCoy. Reprinted by permission of Hyperion Books for Children. All rights reserved.Another reason for avoiding up-to-date technology is its propensity to take over. I'm sure you know the kind of picture books I'm talking about: preachy, predictable ones that demonize The Big Bad Box and spend 32 pages exhorting kids to "Just Say No."

There are notable exceptions to the dreaded rule. One of my favorites is Glenn McCoy's 2002 book, Penny Lee and Her TV, which depicts a neglected pet's quest to cure his owner's television addiction. This results in hilarious outdoor recreation scenes of fishing and jumping rope for Penny Lee, her dog, and her unplugged TV set. Suzanne Collins and Mike Lester's 2002 book, When Charlie McButton Lost Power, similarly addresses technology overload by finding a satisfying way to let its young protagonist discover the pleasures of going without electricity. Caveat: These are topic books about technology, not picture books that happen to include it.

-

© 2008 Barbara Lehman. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

© 2008 Barbara Lehman. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.So are most modern picture books better off staying low-tech? My answer is an emphatic no because a few books have boldly gone high-tech with great results.

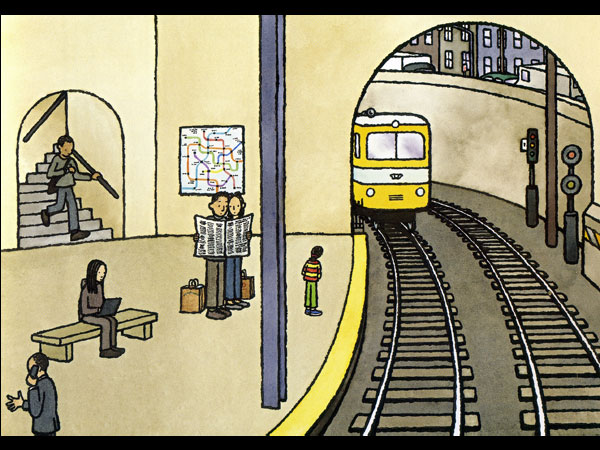

Like most of Barbara Lehman's wordless fantasy offerings, Trainstop begins in a straightforward urban setting: the subway. Lehman shows all the gadgets you usually see underground commuters using: cell phones, BlackBerries, and even an MP3 player with ear buds. As the story proceeds, the train goes through a tunnel and tiny little people arrive. Only the protagonist, a small girl, can see them. The little people work and play with her and then, at the end of the book, show up with a thank-you gift. The realism of the technology-laden commuters in Lehman's opening pages heightens the magic of a child classically glimpsing a world unseen by adults.

-

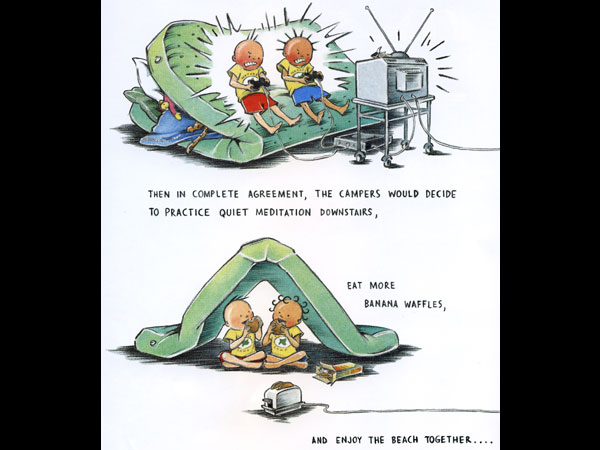

From CREDIT: A Couple of Boys Have the Best Week Ever by Marla Frazee, © 2008 Marla Frazee. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt Children's Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co.. All rights reserved.

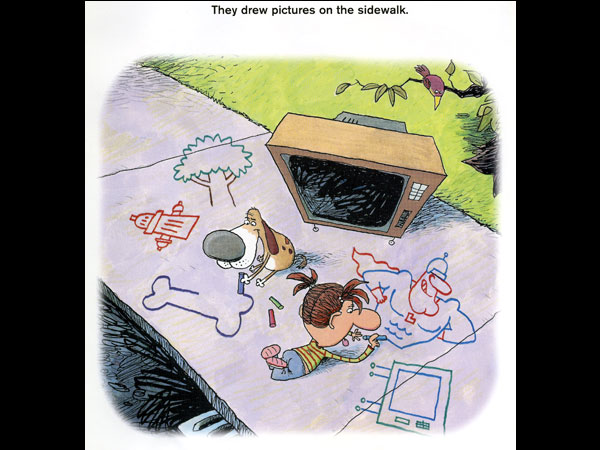

From CREDIT: A Couple of Boys Have the Best Week Ever by Marla Frazee, © 2008 Marla Frazee. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt Children's Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co.. All rights reserved.Another fine high-tech example is Marla Frazee's new book, A Couple of Boys Have the Best Week Ever. Frazee's decision to include both a television and a video-game system makes the book's domestic setting feel familiar to modern kids. Grandma Pam's electric-pump air mattress, used for guests, further grounds the story in a kid's comfort zone. ("Hey, just like at my grandma's house!") The book's premise (best friends spend a week barely tolerating nature camp and reveling in indoor pursuits, before realizing …) has the potential to become moralistic, but Frazee turns out to be driving on a different road altogether. When she describes video gaming as "quiet meditation," she's using humor to show technology for what it is—part of a kid's world, along with stuffed animals and banana waffles and well-meaning adults who bring maps to the breakfast table to try to teach them stuff. The book's lovely ending, in which the boys have the most fun they've had all week by building a world out of shells, rocks, and driftwood, shows the value of letting kids come to the great outdoors on their own terms.

-

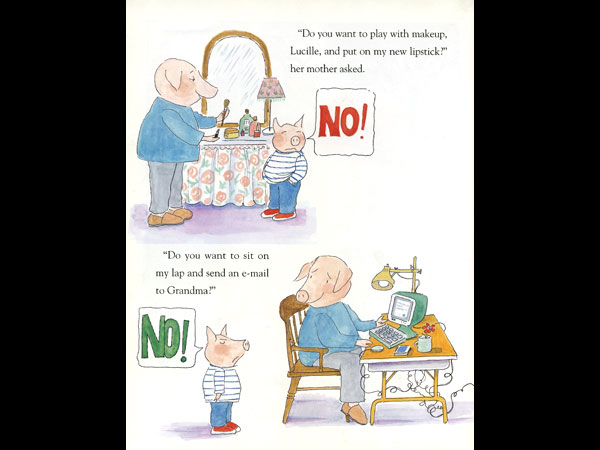

From CREDIT: Lucille Camps In. Used with permission of Marilyn Hafner.

From CREDIT: Lucille Camps In. Used with permission of Marilyn Hafner.I've also been impressed by a handful of recent books that use modern technology to breathe new life into domestic dramas. One example is Lucille Camps In, in which Kathryn Lasky uses Internet access to highlight the universal and timeless plight of the younger sibling. When Lucille doesn't get to go camping with her dad and older siblings, Mom offers perks to make up for her disappointment. The first is traditional: "Do you want to play with makeup, Lucille, and put on my new lipstick?" The second is a modern variation: "Do you want to sit on my lap and send an e-mail to Grandma?" In Marilyn Hafner's illustrations, Lucille answers both questions with an emphatic "NO!" The e-mail reference adds a contemporary touch to the classic ploy of mollifying children with special grown-up privileges. Just as classically, Lucille is wise to the ruse.

In Clarice Bean, Guess Who's Babysitting? Lauren Childs uses technology to add a modern dimension to another timeless domestic theme—the inequality of parental roles and responsibilities. Early in the book, Mom, on a land line, tries to find a last-minute babysitter for her four children while Dad, on his cell phone, says, "I'll be with you in two shakes, Bernard" before going away on Important Business. Under Uncle Ted's watch, chaos ensues, though Mom returns just in time to steer the household back on course.

-

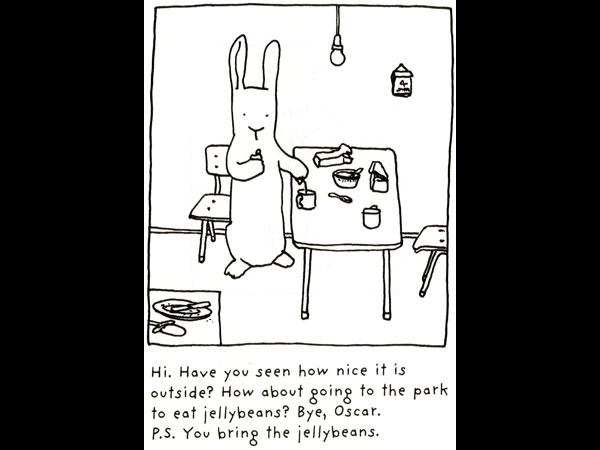

Illustration © Sylvia van Ommen from CREDIT: Jellybeans, used with permission of Roaring Brook Press.

Illustration © Sylvia van Ommen from CREDIT: Jellybeans, used with permission of Roaring Brook Press.Perhaps the most enduring theme of children's literature is the value of true friendship. One book has pulled off using modern technology to update this message (and not by using "to friend" as a verb).

In Sylvia von Ommen's Jellybeans, published in 2005, a cat named George and a rabbit named Oscar plan to get together by text-messaging on their cell phones. Then they meet at a park. (George bikes there, carrying a side-slung messenger bag with a cell-phone pocket.) They sit quietly together. They eat jellybeans and share a thermos of cocoa. They wax philosophical about life, death, and friendship.

The beauty of Jellybeans is that text messaging brings George and Oscar together so they can hang out just like Frog and Toad did in the 1970s. Or Winnie-the-Pooh and Piglet did in 1926. Or Mole and Ratty did in 1908. Two friends who need nothing more than each other's company.

-

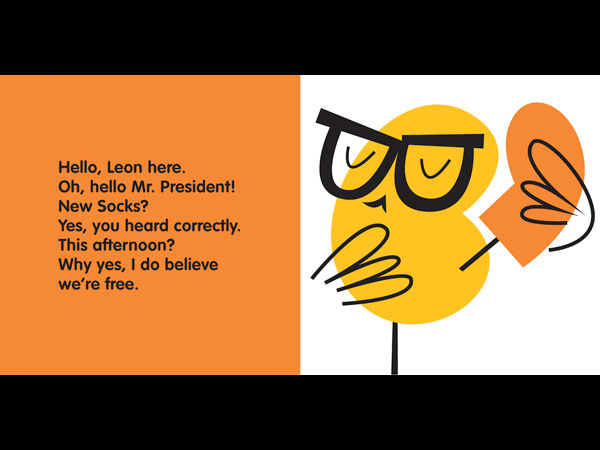

From CREDIT: New Socks by Bob Shea, © 2007 Bob Shea. With permission of Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.

From CREDIT: New Socks by Bob Shea, © 2007 Bob Shea. With permission of Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.At the same time, there's still plenty of room for books that invert our high-tech obsessions. For example, consider the small, bespectacled bird in New Socks. He desperately wants to call the president of the United States to brag about his brand-new bright orange socks. Why should he limit himself to a corded phone, a cordless phone, or a cell phone? Old technology, new technology … who needs any of it?

Nothing less than a sock phone will do.

Click here for a slide show on technology in children's literature.