India’s Deadly Heat Wave

Photo by Sanjay Kanojia/AFP/Getty Images

One of the worst heat waves in recent history is underway in India, with BBC News reporting that more than 1,000 people have died in less than a week. The Hindustan Times reports that most of the victims are construction workers, the elderly, or the homeless. Local governments are calling for drinking water camps and public education campaigns with heat safety tips—measures that aren’t likely to help much. In India, most people dying from the heat are likely too poor to afford to take a break from work to cool down.

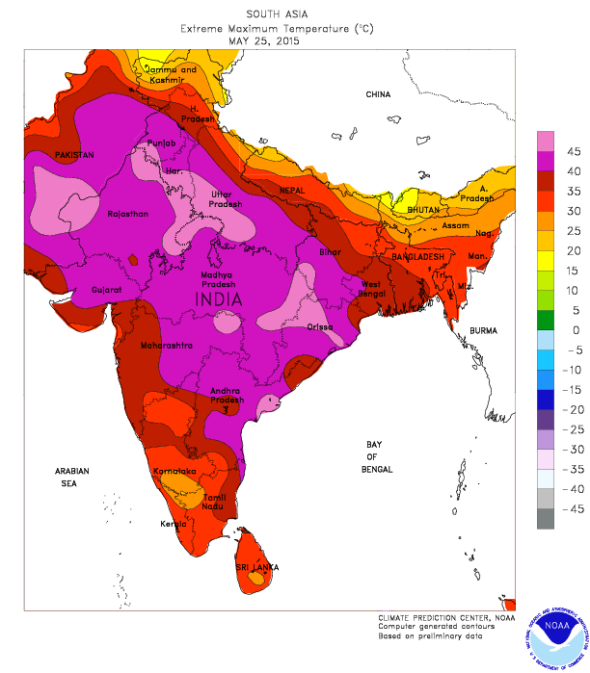

In the hardest-hit areas, temperatures have been up to 10 degrees Fahrenheit above normal for several days during what is usually the hottest time of the year. In New Delhi, temperatures were so hot—reaching 113 degrees Fahrenheit—they melted the roads. In Hyderabad, 26 of 31 days this month have been or are forecasted to be hotter than normal. According to India’s Meteorological Department, the temperature hit a stunning 117 degrees Fahrenheit on Tuesday at Titlagarh in Odisha—the hottest temperature nationwide, and just 5 degrees below the country’s all-time record.

Watch: This road in Delhi melted due to scorching heat http://t.co/loRaAPTxTF pic.twitter.com/9oaJ3lCUQ3

— Hindustan Times (@htTweets) May 27, 2015

But at least these places had a “dry heat,” and overnight temperatures have been falling into the 80s. Along the coast, temperatures were slightly lower, but much higher humidity levels created a punishing heat index that persisted throughout the night. In Mumbai, for example, the heat index bottomed out just below 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and only for a few hours overnight Wednesday. In severe heat waves, oppressively hot overnight temperatures are extremely deadly, because there’s just no chance for overheated bodies to cool off.

That means the “misery index”—a creation of Web developer Cameron Beccario that factors in both heat and humidity—is off the charts nearly nationwide.

Map credit: Cameron Beccario/earth.nullschool.net

Next to parts of the Amazon River basin, coastal India typically experiences the highest heat indexes of anywhere on the planet. And global warming is making it worse. A recent study in Nature Climate Change showed that increasing heat stress is already limiting India’s labor capacity—the ability for humans to do work outdoors—with side effects including fainting, disorientation, and seizures. According to a separate study, heat stress will be increasingly deadly in the years to come. With more than 250 million farmers, nearly as many as the entire population of the United States, this is a recipe for disaster.

The combination of exceptional heat stress and a still largely rural economy makes India uniquely vulnerable to heat waves. Last year Prime Minister Narendra Modi made universal electricity access by 2019 a key part of his election platform. (Currently a quarter of the country’s 1.25 billion people don’t have electricity.) Air conditioning use in India is growing at a whopping 20 percent per year, putting a huge strain on the country’s still fragile power grid and boosting its greenhouse gas emissions. Electrifying India is a major challenge, and arguably the single most important use of a dwindling global carbon budget. Beyond India, skyrocketing air conditioning demand in poor countries poses tough ethical questions—it’s hard to justify growing greenhouse gas emissions in relatively wealthy parts of the planet when people are literally dying of heat in the tropics.

Conditions like this—horrible heat, and the vast majority of people without access to air conditioning—will continue until the monsoon season arrives in early June. The Indian monsoon is, in my opinion, the most important weather forecast in the world, and the outlook for this year’s rains isn’t great. With so many farmers dependent on the rains—which produce 70 percent of the year’s total rainfall in just four months—the monsoon is sometimes called “India’s real finance minister.” Though the rains are expected to arrive on time this year, the seasonal total could disappoint for reasons similar to last year’s failure: A growing El Niño and an unfavorable distribution of heat in the Indian Ocean could stifle thunderstorms. Should the monsoon’s northward progression stall out like last year’s, India could have several more weeks of scorching heat to come.