It’s about to start raining in India, but not quite yet.

That’s big news in a country where about half of the 1.25 billion population is engaged in agriculture. Each year, 70 percent of India’s annual rains come during the summer monsoon months of June to September, when rising warm air over the subcontinent draws moisture northward from the relatively cooler Indian Ocean. This year, thanks in part to El Niño, the outlook is grim.

The added stress of past failed monsoons has been deadly for India’s farmers: Suicides are increasingly common in rural areas, especially in drought years. Though the government has plans to expand irrigation to reduce reliance on the rains, most of India’s farmers are still dependent on rainfall.

Meanwhile, the country is currently in the grips of a sweltering heat wave, with temperatures expected to max out between 108 and 116 degrees Fahrenheit (42 to 47 Celsius) in New Delhi for each of the first 10 days in June. That kind of heat is literally off the charts, with temperatures currently averaging up to 18 degrees Fahrenheit (10 Celsius) above normal across much of the northern part of the country, challenging all-time records. The heat won’t relent until the monsoon arrives.

Image: India Meteorological Department

Unfortunately, the developing El Niño—a periodic warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean—is probably already disrupting the typical monsoon circulation. The monsoon rains normally arrive on the southern tip of India around June 1, but this year there’s been a delay of several days. The leading edge of the monsoon rains are still well offshore the mainland.

This time of year, Indian meteorologists are national news figures and their outlooks can help steer national politics. In April, the Reserve Bank of India warned that a weak monsoon could boost inflation nationwide. The New York Times lists El Niño as one of the biggest challenges for the new Modi government: With possible drought comes the potential for weakened economic growth. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to call this the single most important weather forecast in the world.

With so much on the line, that puts big pressure on meteorologists to get it right. But they don’t always. Monsoon forecasting in India is still a relatively young and inexact science, using mostly relatively simple statistical methods. A new forecasting system, implemented this year on an experimental basis using India’s most powerful supercomputer, promises better results. So far, the stats-based forecast and the experimental supercomputer forecast haven’t disagreed significantly.

Official forecasts say this year’s rains will be 95 percent of normal, but there’s reason to believe the monsoon will produce less rain than that. Since the India Meteorological Department issued its first forecast in late April (PDF), confidence has increased that the monsoon rains will disappoint.

That’s mostly because El Niño-like conditions have essentially already taken hold over the tropical Pacific Ocean. In its latest update, the International Research Institute for Climate and Society said there’s now about a 70 percent chance that a full-blown El Niño will be in place by the time the monsoon rains end, a distinction that would require only a slight further warming to achieve. During an El Niño, thunderstorm activity shifts eastward away from southern Asia toward the middle of the Pacific Ocean, helping to weaken the monsoon circulation over India.

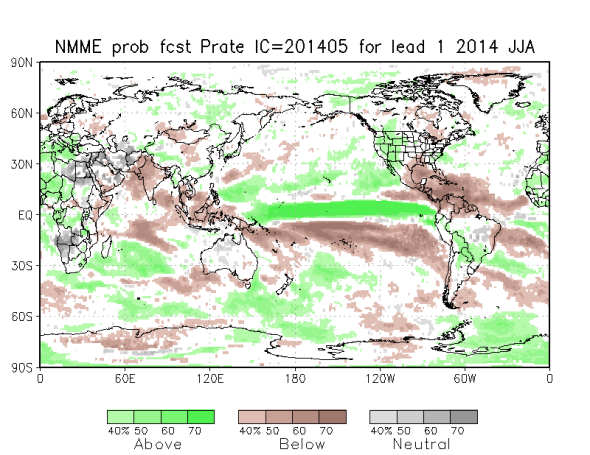

As of mid-May, not one of the eight component models of NOAA’s National Multi-Model Ensemble show India’s rainfall to be near- or above-normal from now through the end of August. Next to the Caribbean/Central America region, that’s the highest confidence of drought of anywhere on the globe for the next three months.

Image: NOAA National Multi-Model Ensemble

Adding to the increasing confidence of an abnormally dry monsoon is the wildcard of the Indian Ocean Dipole. The positive phase of the IOD—an abnormal warming of the western Indian Ocean that’s linked to, but not dependent on, El Niño—could help blunt the drying effect expected this year in India. The bad news is, the latest forecasts show it likely won’t arrive until at least October, after the Indian monsoon has finished, if it arrives at all. Recent research has shown the IOD acts to modify the larger signal of El Niño when it comes to the Indian monsoon. According to the findings:

- When an El Niño event occurred independently without a positive IOD, the monsoon season broke down and the rains failed.

- When a positive IOD occurred with an El Niño event, rainfall during the monsoon season was generally average.

- When a positive IOD occurred without an El Niño event, rainfall was generally above average.

Unfortunately for India, so far it’s looking like 2014 will end up in the first case.