We’d All Be Safe and Dry Right Now If Not for the Fujiwhara Effect

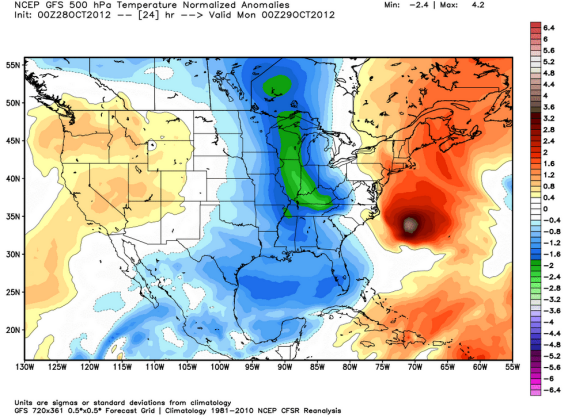

Image courtesy of Ryan Maue / WeatherBELL Analytics

A week ago, as Sandy was coalescing down in the Caribbean, the United States’ best models predicted that the hurricane would mosey up the coast and then sail harmlessly out to sea. But a European model predicted something stranger and more sinister: that Sandy would, in essence, lock arms with a low-pressure trough over the Eastern United States, which would pull it inward toward a potentially devastating landfall on the East Coast. As of last Tuesday, Mark Sudduth at HurricaneTrack wasn't sure which one to believe.

As is obvious to all those getting slammed by the storm today, the European model was basically right. But just how did that wintry extra-tropical storm manage to pull Sandy ashore? As Columbia University professor and atmospheric scientist Adam Sobel explains in a guest post on Climate Central, the do-si-do is the product of a meteorological phenomenon called the Fujiwhara Effect.

Named after the early-20th-century Japanese scientist Sakuhei Fujiwhara, the effect describes what happens when two cyclonic vortices interact. As Sobel wrote in his blog post on Saturday:

If two vortices come close enough to each other to get caught in each other’s flows, then each one acts like the cork; its center moves in the flow swirling around the other one. At the same time, if one is moving, the center about which the other is moving is itself moving, and vice versa, and the two carry out a joint maneuver. Or a dance. Hurricane Sandy is moving into position to do this dance with the upper-level trough whose eventual predicted merger with it has led to the “Frankenstorm” nickname.

It’s most commonly observed with pairs of tropical cyclones, often in the West Pacific. But an animation by meteorologist Ryan Maue of WeatherBELL Analytics showed how something similar could happen with Sandy and a big wintry storm in the North Atlantic (see animation below). That’s more or less what seems to be transpiring today.

Some explanations of the interaction have just described it as a simple merger of the two systems. But Sobel maintains that it’s appropriate to view it in terms of the Fujiwhara effect, since in fact Sandy has been pulled westward while pushing the extra-tropical system to the south. If it weren’t for this rare confluence of events, Sandy wouldn't be wreaking nearly so much havoc right now.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University.