In Defense of Instagram: Why News Photography Goes Well With Vintage-Filtered Cat Pics

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

If its critics are to be believed, Instagram is one of the best deals in the world. The totally free app, and others like it, turn the work of talentless amateurs into “fine art.” Or so photographer Nick Stern argued last week in a piece on CNN that made the software sound like magical wowie-zowie dust.

In his much-discussed article—called “Why Instagram photos cheat the viewer”—Stern objects to using cell phone apps to create news images, decrying the way the software can manipulate photos, adding dramatic color enhancement and faking selective focus. “The app photographer merely has to click a software button and 10 seconds later is rewarded with a masterpiece,” he writes.

AFP/Getty Images.

Stern’s article touched off heated debate among the photojournalism world, which has been struggling to define the role of cell phone photography in the changing digital landscape. Like Stern, I find myself annoyed when otherwise mediocre news images get prominently promoted on a Web site just because they have a gimmicky-app-enhanced color scheme. Like Stern, I think that dramatically altering a news image after it’s taken—by shifting the point of focus or the color of, say, a bomb blast—is unacceptable whether it’s done with a cell phone tool or with desktop Photoshop. But I still disagree with the basic premise of Stern’s argument. Instagram is not a threat to photojournalism. The real threat is that photojournalism professionals are refusing to engage with the platform. If they spent a bit more time with it, they’d see that Instagram is about much more than these faux-vintage-filters. It’s a community of millions of photo addicts, eager to embrace their work, journalistic standards and all.

I understand Stern’s skepticism. I was there five months ago, telling friends to shut up about “Instamatic.” (I assumed the app Instagram was the same as another popular photo app, Hipstamatic.) But the two apps are not the same, as Stern casually implies in his piece by grouping them together. While Hipstamatic is primarily a means to make cell phone photos cooler with filters, Instagram is a massive, daily-routine-altering photo-sharing network. What’s remarkable about the app is not the filters; it’s the audience. Instagram is home to a community of photo-lovers that has grown from 1 to 15 million in a single year. In January, the number of photos uploaded surpassed the 400 million mark. Though not anywhere near the scale of Flickr at this point, Instagram boasts a simple mobile platform that is enabling it to grow quickly. Serious Instagrammers interact with their feeds—uploading their own photos, and liking and commenting on others’—several times a day. This is the type of interaction Web sites die for.

AFP/Getty Images.

But Stern, like many others in the photojournalism world, is too distracted by the idea that Instagram is cheating to discover these advantages. “The app photographer hasn't spent years learning his or her trade, imagining the scene, waiting for the light to fall just right, swapping lenses and switching angles. They haven't spent hours in the dark room, leaning over trays of noxious chemicals until the early hours of the morning,” Stern writes, echoing a sentiment I’ve heard many times before. “Nor did they have to spend a huge chunk of their income on the latest digital equipment ($5,999 of my hard-earned cash just went on ordering a new Nikon D4) to ensure they stay on top of their game.”

Stern sounds a bit retrograde here—you don’t need expensive equipment to take great pictures, as professionals like New York Times photographer Damon Winter and Ben Lowy (who shot an award-winning series in Libya on his iPhone) have proved. But Stern also needn’t worry that a free app will allow newbies to replicate professional photographers’ skills.

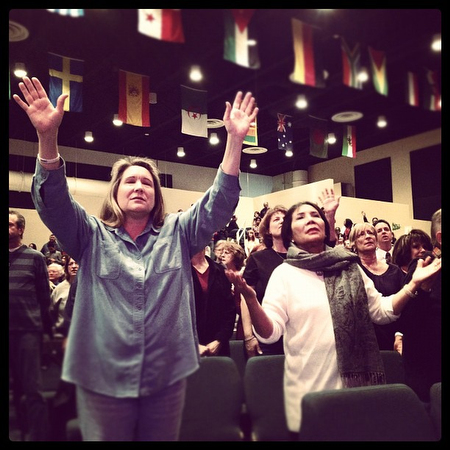

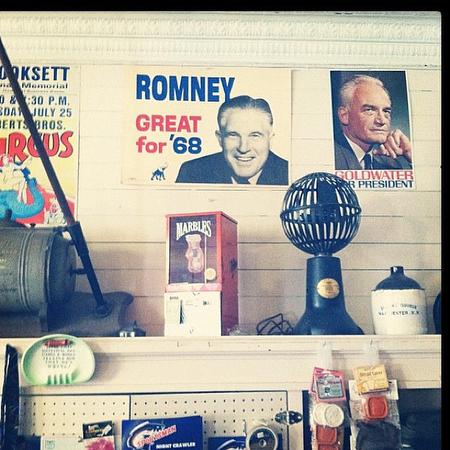

As reactions to Stern’s article began to flood my Twitter feed, I happened to be deep in the Insta-trenches. I was hoping to make a gallery of great Instagram campaign photos. But even as I hopped among dozens of feeds, searching through hashtags like #Politics and #2012election, I struggled to find 20 images I’d want to share. Yes, there is a lot of genius stuff on Instagram—fashion photos, street photography, architectural studies, you name it. But in terms of photojournalism, there’s little that could be mistaken for professional, as Stern and others fear.

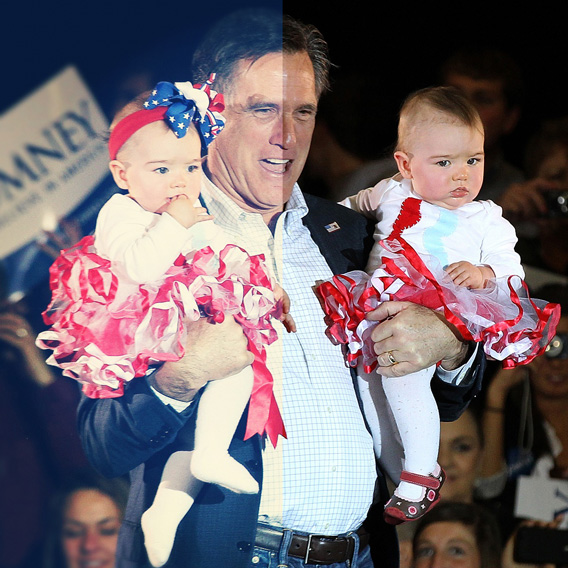

Thanks to the fact that a few news organizations and photojournalists are experimenting with this realm, I was able to find the images above. But combing through thousands of dull, out-of-focus images taken along the campaign trail reinforced the point that an app alone doesn’t make a good picture. You cannot fake a real moment with weirdly placed blur; you cannot hide compositional flaws with a filter that reminds you of your parents’ wedding photos.

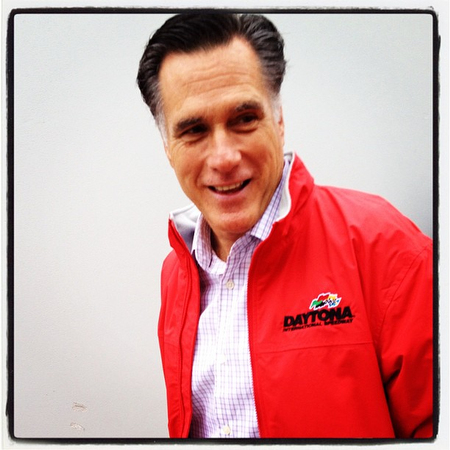

What Instagram can do is help novice photographers get their feet wet. New York Times reporter Ashley Parker, who has been covering Mitt Romney and Instagramming her way through the political campaign, acknowledges her lack of photographic experience. “I’m just not a great photographer,” she tells me over the phone. “That’s why I love Instagram so much. It’s an amazing shortcut … I can’t do it on my own.”

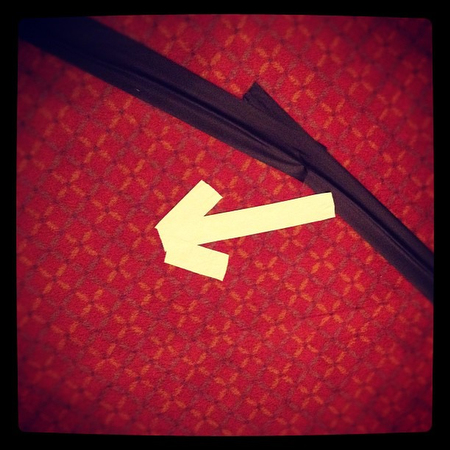

It’s true that Instagram processing helps spice up Parker’s photos. It makes Mitt Romney’s red Daytona jacket pop (helpful, since his face is a bit out of focus), and the Romney supporter she shot in an “I Can’t, I’m Mormon” sweatshirt looks extra retro-sweet (despite the elderly man looming awkwardly behind her). While she’s doing great for a writer—and evidently getting better as she goes—there is no mistaking these for images by a professional. These photos, published in her own personal feed, will never make it onto A1. In fact, they rarely even make it onto the politics blog. In the meantime, though, something very good is nonetheless happening; reporters like Parker are learning about photography while sharing behind-the-scenes tidbits. Campaigns, we all know by now, are big charades; little deconstructed moments like the directional tape on the floor help make them more interesting, accessible, and real.

I like a dash of behind-the-scenes photojournalism with my vintage-filtered cats in the morning. But as I scan my Instagram feed before I get out of bed, the politics I find is generally put there by people in the process of learning how to make a picture.

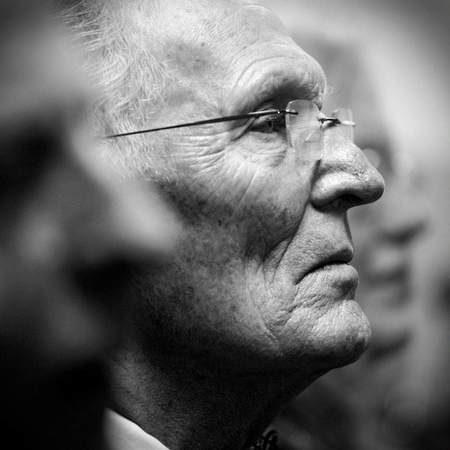

John W. Poole / NPR

What I think many members of the photo community may be missing is that Instagram users don’t have to post iPhone photos (it is possible to upload photos taken with a better camera), and they can transparently refuse filters (people do it all the time, often tagging their images #nofilter). Instagram is a quickly-changing ecosystem that anyone can enter on his or her own journalistically lofty terms. They just have to be willing to play.

“It’s like when people started moving to the Web in ‘95,” said John Poole, a photographer and videographer for NPR, one of the few news organizations to post campaign photos by professional photographers in its feed, instead of using it solely for lower quality outtakes by political reporters. Poole, who started at washingtonpost.com back when it was still more of an experiment, is familiar with the freakouts inspired by change. But he says that many members of the photojournalism world are missing an opportunity by acting as if they’d be tainted by participation. “People don’t understand it necessarily, but some idea they’ve gotten of it touches a nerve, and so they start projecting all this garbage onto it, regardless of whether it’s applicable to Instagram,” he said.

Before NPR sent him and photographer/multimedia trainer Becky Lettenberger out on the trail, they had a discussion about how Instagram would be incorporated into their workflow.

“We decided we weren’t going to use any filters, and if we were it would just be toning [their pictures] to black and white,” Lettenberger explained. Although the details of the process have evolved, the photos are essentially held to the same standards used on NPR.org.

The form offers certain rewards that Poole had never experienced before as a photographer—such as instant feedback. Thanks to NPR’s many Instagram followers (115,908 at my last count), Poole is able to check images in the feed and “see the 'likes' accumulating.” He said that monitoring viewer response helps him understand more about what photos are resonating with people. He gets a certain satisfaction from reading people’s comments and watching a photo taken while on the campaign trail surpass the “likes” of, say, a famous musician’s portrait.

Poole is hitting on something here that many Instagram critics are missing: It’s fun. Scanning my Instagram feed is less like reading a news site than playing a game. There is something absurdly enjoyable about evaluating a professional photographer’s photo of Jon Huntsman with a goat (does it deserve a “like”? yes) alongside a friend’s blurry pic of her date (no). I can experience photos from photojournalists I admire (the handful who are on the platform), just a few seconds after they took them. I can leave them a question in the comments—and they might answer. They might even like my photos back.

Of course, Instagram should not be a substitute for other, more formal outlets for presenting photographs. But professionals who are dismissing this new way of connecting with fans, because they happen to detest an optional filter, are severely missing out.

More posts on photography: