Sunlight and a spot of calcium

[Note: At the bottom of this post is a gallery of amazing pictures of the Sun from Earth and space!]

It's so easy to take the Sun for granted. Too bright to even look at, we tend to think of it as a featureless white (or, misleadingly, yellow) disk, bereft of detail.

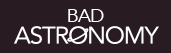

But then you see something like this, and it's like a physical blow to your brain:

[Click to get access to the massive 2400 x 2500 pixel version of this (once there, click the "download" link).]

Holy heliotropism. Seriously.

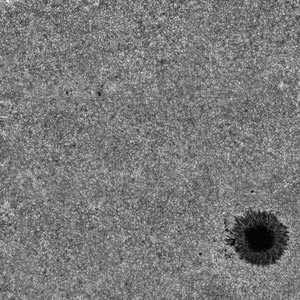

What you're seeing here is small region on the Sun's surface at incredible resolution. This image shows an area of about 200,000 by 200,000 km (120,000 x 120,000 miles), only about 0.5% of the Sun's visible disk. Yet the detail is amazing! The full-res version of this image shows features as small as a couple of hundred kilometers across -- bear in mind, the Sun is a whopping 1.4 million kilometers (860,000 miles) in diameter!

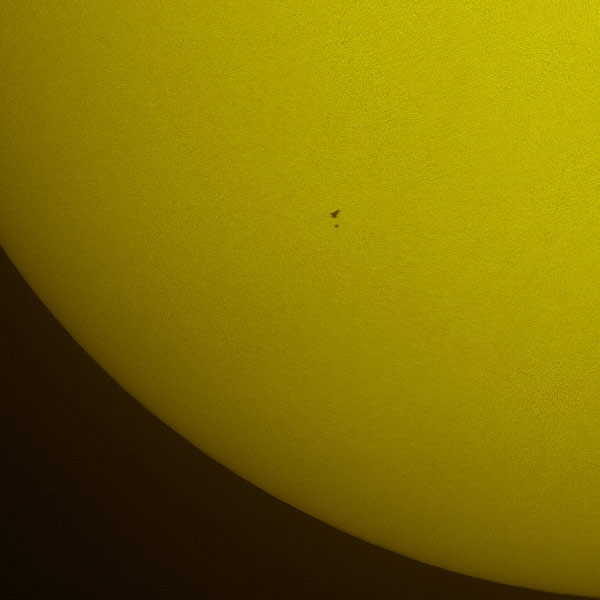

To give you an idea of what you're seeing, take a look at that sunspot in the lower right corner. See the roughly disk-shaped dark inner portion of it? Yeah, that's the same size as the whole frakking Earth!

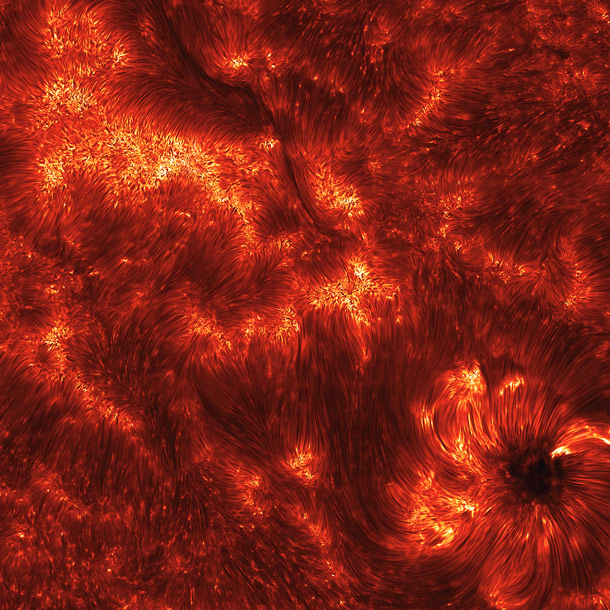

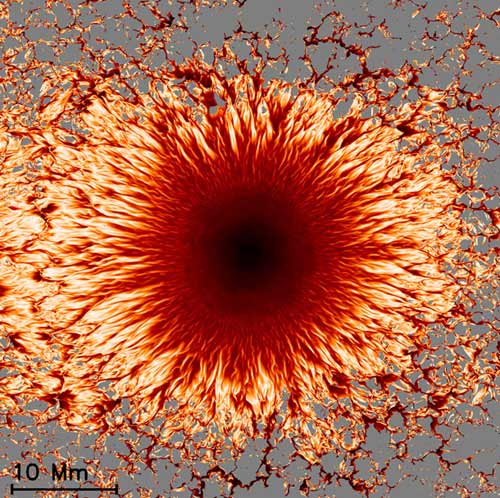

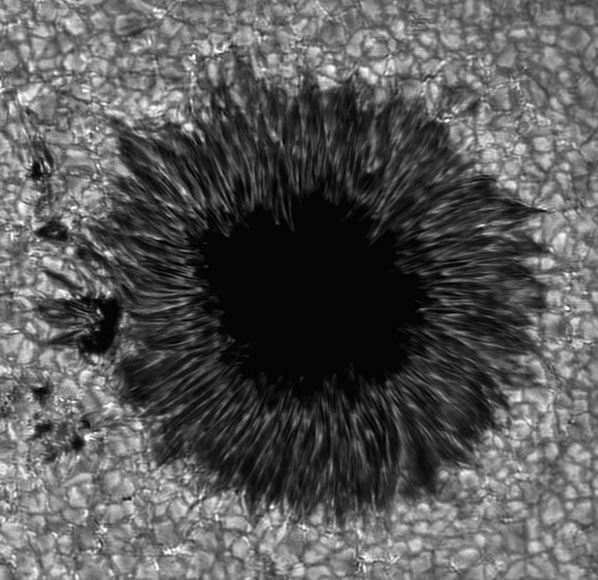

Here's a zoom of the sunspot, taken in a way to show more detail:

Holy wow! Sunspots are where the Sun's magnetic field breaks through the surface. Plasma -- that is, gas stripped of one or more electrons, allowing it to be affected by magnetic fields -- under the influence of that magnetic field cools off, so it doesn't emit as much light as the rest of the surface. That makes sunspots look dark in contrast, but if they were floating by themselves in space they'd actually be very bright (think of a flashlight in front of a spotlight if that helps). Look at all the tendrils and structure inside the spot; that's all due to the way the gas is flowing under the influence of the tremendous heat of the Sun and its powerful magnetic field. These images were taken with a very powerful camera called IBIS -- the Interferometric BIdimensional Spectrometer -- mounted on the Dunn Solar Telescope in New Mexico. The details of the detector are complex, to say the least (if you're an astronomy engineering nerd then you can read this overview of it). The important thing is that IBIS can take images of the Sun at phenomenally high resolution both spatially (it can see tiny regions clearly) and spectroscopically (it can take razor-thin slices of the colors of an object). The former is important to see small details, of course, making the images above so spectacular. But the latter is critical scientifically, because different elements emit light at different wavelengths. Being able to sample those colors at extremely high resolution allows a vast amount of physics to be teased out of images such as this.

The orange color of the first picture is actually a bit of a cheat: the camera used to take it (see below) can examine colors in extremely fine slices, and this is a very narrow region in what is actually the near-infrared part of the spectrum (854.2 nanometers). That's where the element calcium emits light very strongly, so in this image you're seeing how calcium behaves on the Sun.

The close-up sunspot picture was taken at a different wavelength, though -- 543.4 nm to be specific -- so it shows different structures, different details of the Sun's surface. I've included the whole image here on the right (again, click it to get access to a hugely embiggened version). In it you can see the granulation in the Sun's surface caused by gigantic convection cells; towering columns of hot plasma rising up from underneath the surface of the Sun. They cool and then sink back down, like boiling water in a pot.

The close-up sunspot picture was taken at a different wavelength, though -- 543.4 nm to be specific -- so it shows different structures, different details of the Sun's surface. I've included the whole image here on the right (again, click it to get access to a hugely embiggened version). In it you can see the granulation in the Sun's surface caused by gigantic convection cells; towering columns of hot plasma rising up from underneath the surface of the Sun. They cool and then sink back down, like boiling water in a pot.

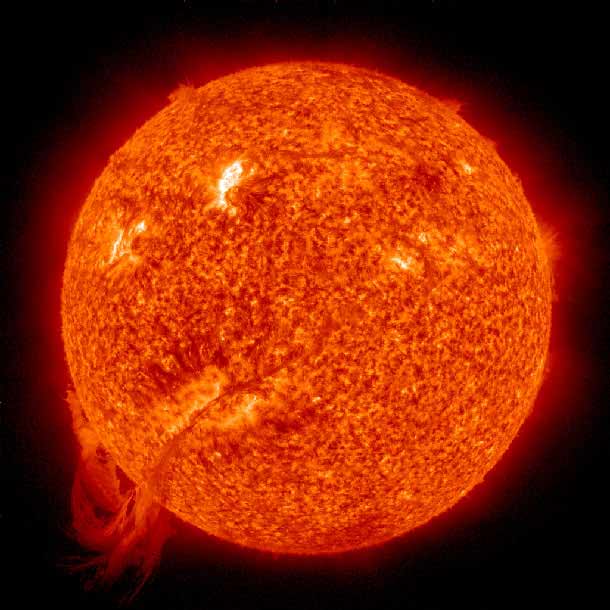

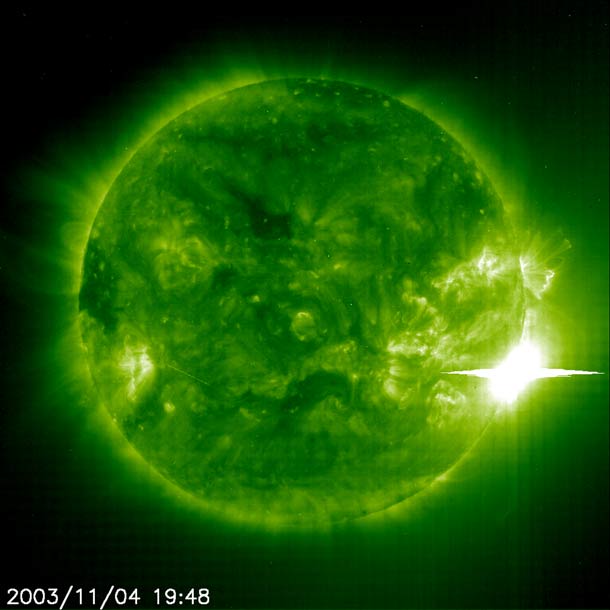

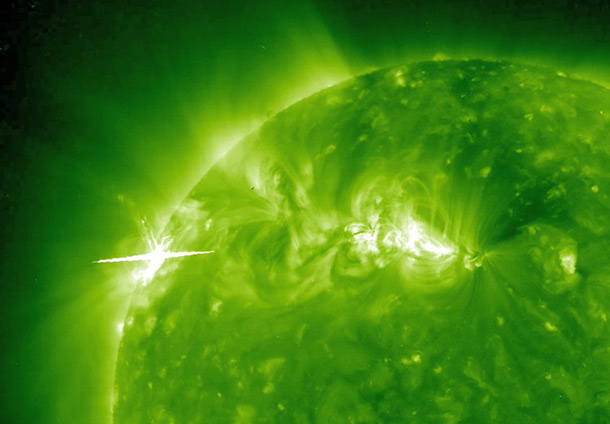

Right now, the Sun is ramping up toward its period of maximum magnetic activity in 2013 and 2014. As the magnetic field gets stronger and more chaotic, we can expect to see more sunspots, and more associated solar flares and other vast explosions from its surface. I'm glad there are so many solar astronomers poring over images like these, trying to understand better the seething, roiling power of this mighty star sitting so close to us. We owe our entire existence to it, but it's an uneasy relationship. The more we know, the better.

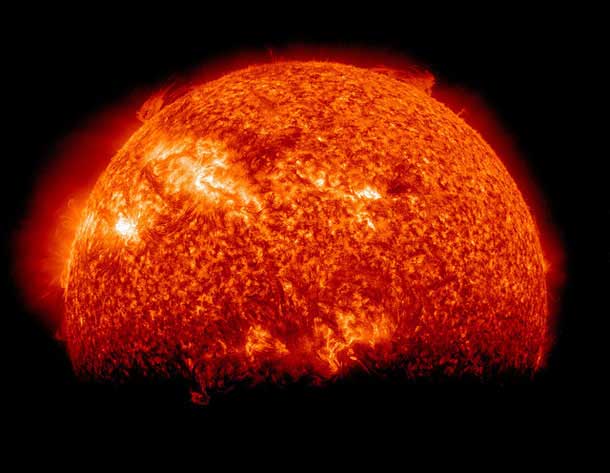

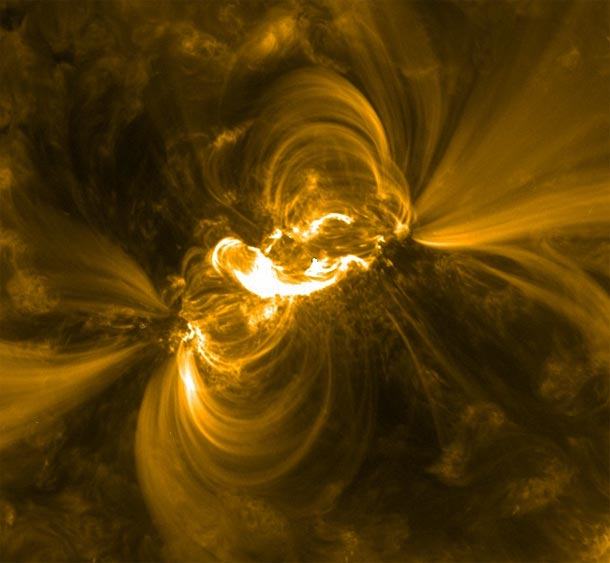

Here are some other amazing images of the Sun! Use the thumbnails and arrows to browse, and click on the images to go through to blog posts with more details and descriptions.

Bad Astronomy Gallery

(click any image to see it full size)

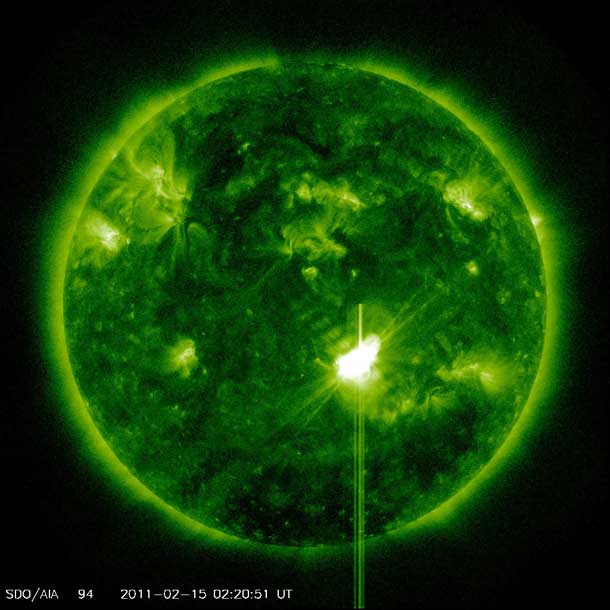

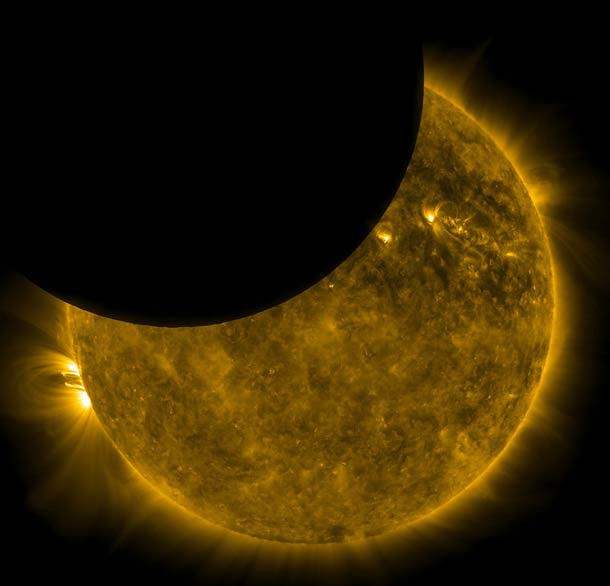

Credit: NASA/SDO

Original blog post

Credit: Thierry Legault

Original blog post

Credit: NASA/SDO

Original blog post

Credit: NASA/SDO

Original blog post

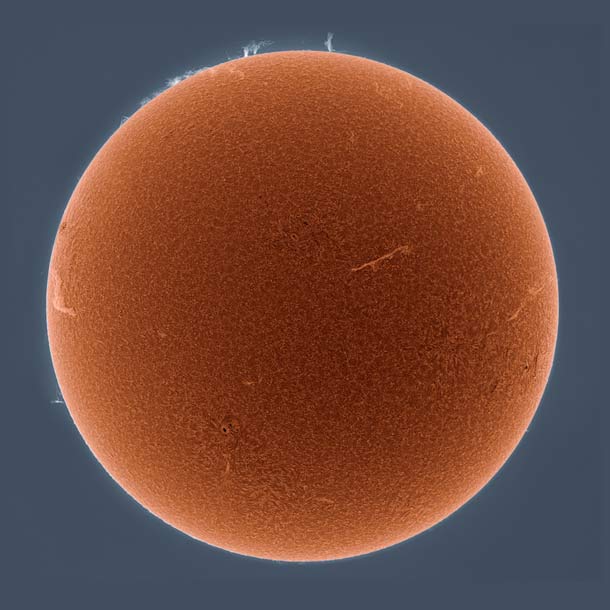

Credit: Alan Friedman

Original blog post

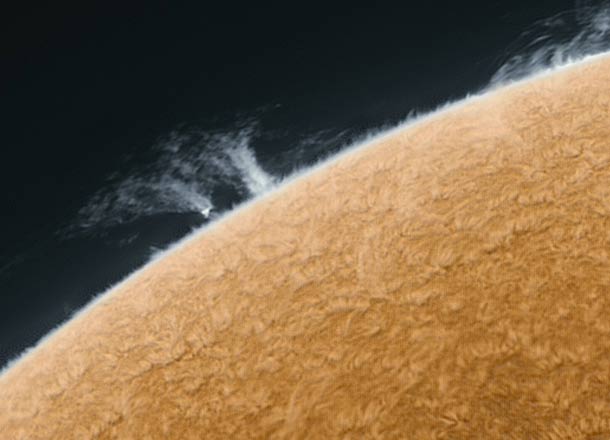

Credit: Alan Friedman

Original blog post

Credit: NASA

Original blog post

Credit: Matthias Rempel, NCAR

Original blog post

Credit: NASA/SDO

Original blog post

Credit: SOHO, NASA, and the ESA

Original blog post

Credit: Glenn Schneider

Original blog post

Credit: Thierry Legault

Original blog post

Credit: NASA/STEREO

Original blog post

Credit: Glenn Schneider

Original blog post

Credit: NASA/STEREO

Original blog post

Credit: Glenn Schneider

Original blog post

Credit: NASA/SDO

Original blog post

Credit: me!

Original blog post