Bin Laden Walks Into a Bar

Why teenagers love making jokes about 9/11.

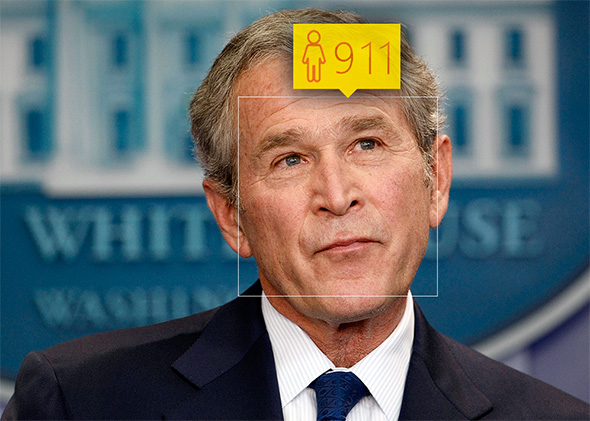

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images and original meme by Phantomazing.

One April morning, a medium-deal teen Vine personality was sitting in his history class, learning about 9/11. The classroom lights blinked off and a warmup exercise projected onto the whiteboard with an enormous photograph of the World Trade Center at the moment that the second plane slammed into the second tower and a gigantic fireball came out the other side. Hundreds of people died in that instant. Thousands more were doomed to wait in the blistering towers until death came for them. Millions watched in horror as the attacks unspooled on live television. But 14 years later, a 16-year-old kid looked at the photograph and saw an opportunity. He pulled out his camera phone, aimed it at the towers, panned to his teacher, and called out, “Mr. Varg? I thought Bush did 9/11.”

“Uhhh,” Mr. Varg said.

Soon the video was looping on Vine over and over again as a jubilant caption cried: “HE PAUSED SO HARD OMG BUSH DID IT GUYS I KNEW IT.” It’s since been played more than 3.4 million times. Every few hours, another teen adds a comment to the thousands already filed: “It’s a conspiracy,” they say. Or “I KNEW IT BRUH.” Or just emoji after emoji for tears of joy.

This is not what that crying eagle envisioned when he told us to never forget. Fourteen years after 9/11, teenagers too young to remember the tragedy in the first place are now mining it for comedy. Some prankster hacked into a Minnesota highway sign last month and reprogrammed it to say “BUSH DID 9/11.” When Steph Curry’s 4-year-old daughter Riley commandeered the mic at her dad’s MVP press conference in May, teen Twitter imagined her spitting lines like, “DICK CHENEY MADE MONEY OFF THE IRAQ WAR.” And this spring, a California high school student surprised one lucky girl with a terror-themed promposal:

Cause jet fuel can't melt steel beams @trutherbot pic.twitter.com/FvGXr1IKlj

— Jesse (@VersacePikachu) May 14, 2015

The modern 9/11 joke takes aim at the truthers, the conspiracy theorists who ruled the Internet fringe in the early aughts. Constructing the joke is often as simple as fishing a conspiratorial slogan out from the Internet’s past and releasing it on the modern Web. The most popular catchphrase of the moment is “jet fuel can’t melt steel beams,” a riff on the truther mantra that fires sparked by planes couldn’t have burned hot enough to tumble the towers, so government bombs probably helped them out. More than 10 years after the attacks, jokesters co-opted the line, and after an incubation period in weird Twitter, it graduated to teen phenomenon last year and confirmed meme this spring. Now, Sept. 11 conspiracy humor is everywhere. A fringe theory materializes in cappuccino foam. A sinister vision of George W. Bush surfaces in the iPhone wallpaper. A local news exposé of “teen texting code” gets warped into truther jargon. A glitch in this novelty photo recognition software points the finger at Bush. The trend stirs up a predictable narrative about kids today: that they have no respect for their elders, that they don’t understand history or appreciate the value of human life, etc. “Dumb kids,” one teacher-in-training scolded on Vine. “9/11 isn’t a joke. Never has been.”

In fact, it always has been. The first 9/11 jokes surfaced online on 9/11. (Here’s one posted to a tasteless jokes board three hours after the first tower fell: Q: What does WTC stand for? A: What trade center?). American studies scholar Bill Ellis spent the months after the attack charting the terror jokes that swirled across the Web, and he found that while most Americans refrained from gallows humor for a week following the attacks, 9/11 jokes soon turned patriotic and played to huge online audiences. Vulgar Photoshops circulated of the Manhattan skyline rebuilt into a raised middle finger and the Empire State Building buggering a bent-over Osama Bin Laden. Anti-Arab slurs leftover from Desert Storm were defrosted and reserved in bizarre jingoistic email forwards, like one that recast Bin Laden as a Muslim Grinch who hated America because, well: “It could be his turban was screwed on too tight/ Or the sun from the desert had beaten too bright.”

These are not objectively funny jokes. But they performed a ritual for many Americans who experienced the attacks on a visceral level even though they had no direct personal connection to the victims. Before 9/11, academics recorded black humor passed between children in the wake of the Kennedy assassination (Q: What did Caroline get for Christmas this year? A: A Jack-in-a-box) and on college campuses in the aftermath of the Challenger space shuttle disaster (Q: What were Christa McAuliffe’s last words? A: “What’s this button for?”). As technology made previously obscure national events personal—schoolchildren and CNN viewers watched McAuliffe and six others die in a live televised spectacle—everyone suddenly needed their own coping mechanism. In a 1991 paper on Challenger jokes, Ellis explored the weirdness of the modern media tragedy: an event “pressed on millions of people who otherwise would be unaffected by it” and are then “bombarded with stimuli to act, while in reality they can provide no actual help.” As newscasters droned on in “clichés of grief,” jokes helped surface the real and complicated feelings produced by a surreal, commercialized disaster.

Sept. 11 was something new—a social media tragedy. Suddenly, horrific news footage didn’t just traumatize everyone in the moment; it lived online indefinitely, and so did all the comments and conspiracies and jokes. Ellis predicted that 9/11 jokes would fade by the end of October 2001, but they persisted, shifting their focus with each iteration: There have been 9/11 jokes about airline security overreach, 9/11 jokes about patriot-xenophobes milking the tragedy, and now postmodern post-9/11 jokes that situate the tragedy as more Internet artifact than open wound. Americans who weren’t even sentient when the towers fell are expected to “relive” the event in the form of traditional tributes but also strange and obsessive videos that lie just below the surface of every YouTube dip. You could even say that making fun of the outdated truther ephemera that floats by on the trash floes of the Internet—the conspiratorial collages, the adult-contemporary power ballads, the YouTube documentaries that make the planes go really slow and also backwards—is a remarkably healthy response to the bizarre new emotional burden that’s been placed on post-9/11 teenagers.

The new generation of 9/11 jokes may not intend to make light of the tragedy itself, but it does have the effect of exorcising the event from America’s collective consciousness. “We all have a basic understanding of the events on Sept. 11 and we have all heard several different types of theories,” but “our interest ends there,” Meghan Autry, a 17-year-old from Georgia, told me. Truthers seem funny now because young people have the emotional distance to see that their theories are plainly ludicrous instead of morally outrageous—the absurdity of a trutherism blowing one’s mind is a persistent trope—but also because truthers are so singularly obsessed with this now-distant event. Young Americans, Autry told me, are more interested in the real government corruption being exposed in police forces across the country in 2015, not in some fake cover-up of a vintage hijacking. When Osama Bin Laden died in 2011, teenagers were ridiculed for being like “literally who?” But the fact that the youth of America are too concerned with police brutality and institutional racism to rehash old controversies strikes me as an unqualified good. Meanwhile, truther jokes themselves have emerged as helpful tools for fighting new and dangerous conspiracy theorists, like the anti-vaxxers skewered in the line “Jet Fuel Can’t Melt Autism Vaccines.” What better justification is there for invoking Sept. 11 in 2015 than to help keep a new generation of children safe?

Recently I called Mike Berger, the media coordinator of 911Truth.org, to tell him that his movement had become the butt of juvenile jokes. Berger didn’t take it personally—“I’ve been doing this a long time, so I’ve had to let go of a lot of my anger,” he told me—but he was frustrated by the way the jokes always reduce complex arguments into easy-to-mock slogans. “There are facts about 9/11, and they’re overshadowed by these crazy memes,” Berger says. “And the more it becomes a meme, the less you have to think about what you’re really saying.” That’s exactly the point. Teenagers have surveyed the digital artifacts left in the wake of their parents’ trauma and decided they were taking up too much cultural space. So they’re flattening them into jokes and throwing them away. A conspiracy theory shrinks into a slogan and then a punch line and then a non sequitur until it’s totally played out. What once constituted controversy will soon be history. Lately, Autry has noticed that the 9/11 jokes aren’t as popular among her peers as they were a few months back. They’re starting to recede into the irrelevant parts of the Internet where adults marvel at teen trends that have already passed. She’s seen them on Facebook.