Going Viral

Google searches for flu symptoms are at an all-time high. Is it time to panic?

Photo by Pixland/Thinkstock.

If you ask the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, this year’s flu season is looking “moderately severe.” That assessment has been reflected in the relatively calm tone of national media coverage in recent weeks.

But wait—if you ask Google Flu Trends, we’re in the midst of an outbreak that is shaping up to be the most extensive on record. Never before this week have so many people searched for the terms that Google believes are likely indicators of the influenza virus. If Google’s algorithm is accurate, that should translate to a volume of doctor visits that significantly exceeds that of the H1N1 outbreak in October 2009. The media usually loves a good health scare. So why isn’t anyone sounding the alarm?

Because, four years after Google Flu Trends launched, the CDC still drives the bulk of national media coverage, suggesting that health reporters aren’t fully comfortable putting stock in Internet algorithms that go back only a few years. Yet Google’s figures may deserve far more attention than they’ve been getting.

By the CDC’s latest “outpatient surveillance” estimates, roughly 5.6 percent of Americans visiting the doctor are reporting respiratory illnesses, or flu-like symptoms. That’s a large number, significantly higher than the national baseline of 2.2 percent or the 2.3 percent peak of last year’s mild flu season. But it’s not entirely out of the ordinary. The figure approached 6 percent in the moderately severe 2007-2008 season and topped out at 7.7 percent in October 2009 in the midst of the H1N1 pandemic.

But here’s the thing: The CDC’s current estimates aren’t all that current. Because they are based on after-the-fact reports from more than 3,000 health care providers around the country, the numbers can tell us only how many people were suffering from the flu a couple weeks ago. Today’s CDC FluView figures, for instance, come from the week of Dec. 23. We won’t know until Friday how many people visited the doctor with respiratory symptoms during the week that began on Dec. 30.

That’s where Google comes in. In fall 2008, the company’s charitable arm, Google.org, unveiled Flu Trends, a site that scans millions of Google searches from around the world to track flu activity in near real time. According to a study published in Nature in February 2009, the system can detect outbreaks nearly two weeks before they show up in the official CDC reports. And the site can tell you on any given day what countries, states, and even cities are likely seeing the largest number of cases.

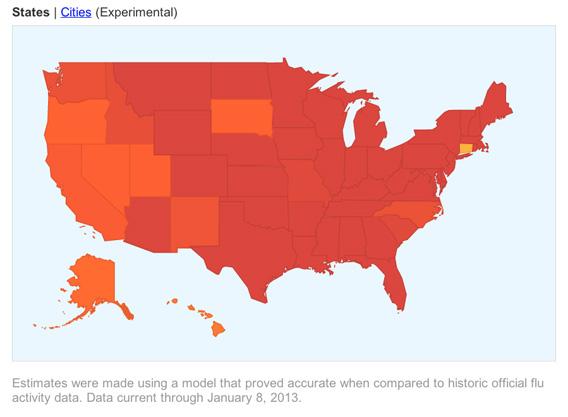

Today, Flu Trends is painting a foreboding picture. On a global scale of green (minimal flu activity) to bright red (intense flu activity), the United States is the reddest country in the world. Zoom in, and the red stretches are almost unbroken across the country’s eastern two-thirds. (Hang in there, Connecticut!) Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Houston, and Denver are among a slew of cities tagged with the “intense” rating.

Screenshot via Google.org.

But the really ominous chart is the one that shows the trend line for the nation as a whole. It roughly agrees with the CDC that flu activity in December was about in line with the “moderately severe” peak in 2007-2008. But if Google is right, the CDC’s snapshot came just as the outbreak was gaining steam. Since mid-December, the trend line has rocketed past that of all previous years and now towers over that of the October 2009 H1N1 pinnacle, suggesting a CDC outpatient surveillance figure of an unprecedented 8.9 percent.

If that turns out to be accurate, the CDC’s Michael Jhung says this year’s would be the most widespread flu outbreak in decades. Jhung, a medical officer in the CDC’s influenza division, said he wouldn’t be shocked if that turns out to be the case, since his own models hint that the virus has not yet reached its peak. But he isn’t ready to go out on that limb just yet. “Is it going to be a more severe season than last year? I think without question,” Jhung said. “Is it going to be a more severe season than a couple years ago, or the previous 10 years? We don’t know, and won’t know until the end of the season.”

Perhaps not. But Google’s track record is disconcertingly impressive. In the four years leading up to the Nature paper in 2009, its estimates lined up with the eventual CDC data with amazing accuracy. The algorithm works by not just counting the number of flu-related searches but weighting specific search topics according to their power as a predictor of the CDC’s doctor visit numbers. For instance, Google has found that searches for antiviral medication are only weakly correlated with the CDC’s findings. But searches for “influenza complications” line up beautifully.

That Google’s algorithm matched CDC data so well between 2004 and 2008 shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. After all, it was built to do just that. The real question is how it has performed in the years since—and whether it could turn out to be way off in an anomalous year, like, say, this one.

While Google hasn’t published a similar report on Flu Trends’ performance in the last few years, Google.org spokeswoman Kelly Mason tells me it has continued to mirror the CDC’s data with similar accuracy—with one exception. In 2009, the first wave of H1N1 came extremely early, hitting between March and August. Google’s model seriously underestimated that spike, according to a paper published in PLOS One in 2011. Google tweaked its model later in 2009 in response to the glitch, and Mason says it hasn’t had to alter it again since then.

The 2009 hiccup should create at least a little room for doubt about Google’s figures this year. The obvious interpretation is that while the model works seamlessly for most seasons, it may stumble in the face of an outbreak that is truly out of the ordinary. Of course, an out-of-the-ordinary outbreak is exactly what the model is currently showing. If it’s wrong, that would be the algorithm’s first major instance of a false positive for a big flu spike.

Before anyone panics, though, there are two other things worth considering about Google’s indications of a flu year surpassing that of 2009. One is that the dominant strain so far this year is H3N2, not the novel “swine flu” strain of H1N1 that spooked the world. That makes this flu season more comparable to that of 2003-2004, which the CDC classified as “moderately severe.” And while H3N2 has been among the deadlier strains in past years, the CDC so far has seen just 18 flu-related deaths among children so far this season—an encouraging sign. During the pandemic, that number was 300.

The second caveat is that even the CDC’s headline metric is not a perfect indicator of a flu season’s severity. Again, the figure to which Google Flu Trends corresponds is the one that tells us what percentage of outpatient doctor visits are flu-related at the institutions in the CDC’s reporting network. But a separate PLOS One study from 2011 found that it doesn’t correlate quite as well with another CDC metric that’s based on the number of laboratory-confirmed cases of the flu. The discrepancy was especially noticeable in 2003-2004, when media attention to an especially early flu season may have triggered a wave of doctor visits and Google searches that turned out not to correspond to actual influenza infections.

All that said, it seems almost certain that the most recent CDC figures are underestimating the outbreak’s current magnitude. Don’t be surprised to see a flurry of increasingly dire warnings and media reports in the weeks to come. In fact, they’re already beginning. But thanks to Google Flu Trends, you can beat the rush. The CDC’s Jhung recommends that everyone over the age of 6 months who has not yet gotten a flu shot do so now.* Even if you’ve already caught one strain, he said, there are still two others that the vaccine can protect against.

If this is indeed the year that Google Flu Trends proves its merit as an early warning system for major flu outbreaks, there will be one sad irony to the timing. Google’s big health initiative, Google Health, was discontinued just last year because, according to Google, it was “not having the broad impact we hoped it would.” Flu Trends lives on for the time being under the Google.org umbrella. But after growing fast early on, Flu Trends has added just one country—Romania—to its 29-nation database this year, and Mason said there are no plans to add more.

Correction, Jan. 10, 2013: This article misstated the age at which the CDC recommends children get flu shots. It's 6 months, not 6 years. (Return to the corrected sentence.)