The Thirsty West: Death Valley’s Looking Pretty Good Right Now

It’s one of the few places in California not currently in “extreme drought.”

Courtesy of Karen Edquist

DEATH VALLEY, Calif.—As the driest place in North America, Death Valley is about as inhospitable a place as you can get on Earth. In fact, NASA frequently uses its barren landscape as an analogue for Mars. Naturally, it was a perfect destination on my drought-themed road trip.

Oddly enough, Death Valley is one of the few places in California that’s not technically in “extreme” drought right now. Its drought is listed as only “severe,” despite having recorded only 30 percent of its average rainfall so far in 2014. As the rainy season staggers to a close, more than 70 percent of the state is currently in “extreme” or “exceptional” drought, the highest two categories as described by the U.S. drought monitor.

When my wife and I arrived, we had just emerged from sprawling Las Vegas. The stark desert landscape was a welcome sight.

The yearly average rainfall here is just two and a quarter inches, or about as much as falls in a single healthy spring thunderstorm in the Midwest. On average, in two weeks New York City can receive what falls here in an entire year. Nearby Las Vegas, with more than 2 million people, manages only twice the rainfall of Death Valley.

This place is both equal to and opposite of Las Vegas. Here, it’s still and breathtakingly quiet. At night, the stars in Death Valley shine nearly brighter than a casino’s neon. Yet, they’re separated by just a two-hour drive and share a very similar climatology.

The reason for Death Valley’s exceptional dryness lies in atmospheric physics. A series of mountain ranges separates this isolated spot from the Pacific Ocean, where the bulk of California’s rain and snow originate. They cast a rain shadow over this valley: Each mountain range squeezes out a bit more precipitation than the one before. By the time these clouds make it to Death Valley, there’s almost nothing left. Air warms as it descends, and dry air warms faster than damp air. Since Death Valley is one of the lowest places on earth, that adds up to an extreme environment.

Surprisingly, in one of the driest places on Earth, the ground is soft and damp underfoot. Death Valley is technically a dry inland sea, and tiny salt crystals are everywhere. Melting snowpack from the surrounding mountains flows down into the valley, where it eventually evaporates, again turning the ground white with mineral deposits. Upon close inspection, it’s fabulously beautiful.

Courtesy of Eric Holthaus

It’s hard to imagine how anything survives here, but more than 1,000 plant species are found within the park boundaries, though few grow in the valley itself. The ones that do are well adapted to the harsh and salty environment.

It’s only once you reach stifling Badwater Basin—the lowest spot in North America, and possibly the hottest place in the world—that things start to get really strange.

A sign hung on the cliff high above the valley floor marks in surreal block letters: Sea Level.

Several years ago, scientists from NASA’s Ames Research Center installed a weather station at Badwater with the intention of verifying eventual new world temperature records. The official temperature measurement for Death Valley is taken a few miles up the road, at the resort town of Furnace Creek.

Meteorological detective Christopher Burt has a comprehensive list of would-be rivals for the hottest place on Earth. Due to sketchy measurements, not many of them hold muster. In fact, in 2012, the long-disputed world record for the hottest temperature ever recorded—an astounding 136 degrees in El Azizia, Libya—was overturned by the World Meteorological Organization, on the grounds that the measurement was improperly taken. That means Death Valley is now the undisputed hottest spot on the planet. Burt played a small hand in getting that record overturned, and his account of the process is fascinating.

Still, the hottest temperature ever measured in Death Valley—134 degrees—was taken more than 100 years ago, and is not without its own controversy. The closest thermometers in this area have come since that day is 129 degrees, the most recent of which was just last year. With the steady upward push of climate change, it’s only a matter of time before Death Valley breaks its own record.

Death Valley’s long-standing title as the driest place in North America is also being challenged. Over the past decade or so, Calexico, a town on the California-Mexico border, has averaged about a half inch less rainfall per year than Death Valley. It’s not clear yet whether this has just been an exceptionally dry run for Calexico, or a sign of things to come, but what’s clear is that the climate in this part of the world isn’t getting any wetter.

We passed through Badwater in the early evening, as the sun was setting. Still, the temperature on our car’s thermometer steadily rose to a peak of about 85 degrees as we descended into the valley.

As we started to climb back into the mountains, it was amazing to consider how delicate, yet resilient life in this valley is. If only we could follow its example.

My next stop on the Thirsty West journey will be in California's high Sierras, where the snow that falls over the winter determines the state's water supply for months to come.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

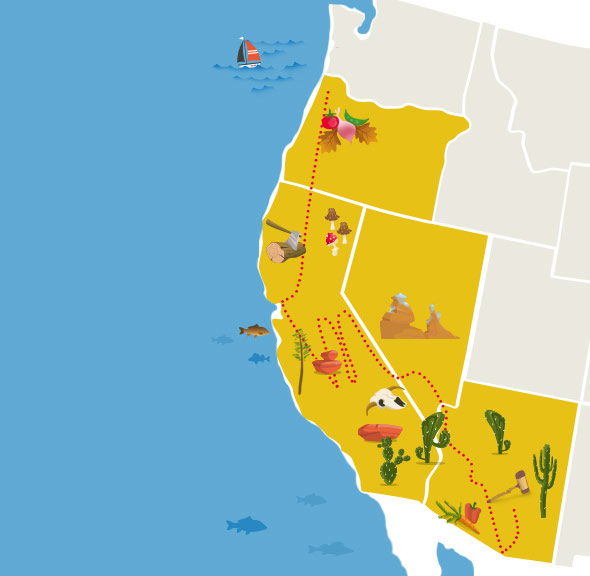

Tucson, Ariz.

Tucson, Ariz.

Nogales, Ariz.

Las Vegas, Nev.

Death Valley

Sequoia National Forest

Hanford, Calif.

Denair, Calif.

Tulare, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Sheridan, Ore.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.