We’ve been to the moon and just about everywhere on Earth. So what’s left to discover? In September, Future Tense is publishing a series of articles in response to the question, “Is exploration dead?” Read more about modern-day exploration of the sea, space, land, and more unexpected areas.

“What an inconceivable experience it is to attain one’s ideal and, at the very same moment, to fulfill oneself. I was stirred to the depths of my being. Never had I felt happiness like this—so intense and yet so pure. That brown rock, the highest of them all, that ridge of ice—were these the goals of a lifetime? Or were they, rather, the limits of man’s pride?”

- Maurice Herzog, 1952

When Maurice Herzog wrote these words, he was recalling his historic ascent of Nepal’s Annapurna—the first time anyone had stood more than 8,000 meters above sea level. On the summit, gasping for air, Herzog was testing the limits of strength and endurance, and bringing vast regions of the high Himalaya into the realm of human knowledge. He was tired, wind-whipped, oxygen-starved, but clearly exhilarated. After all, he was exploring.

Such was the reality of pre-21st-century exploration. It wasn’t for the faint of heart, this life-risking blitz of derring-do, but it was the only way to grasp at the outer edge of the known world, to try and make sense of the universe through knowledge acquisition.

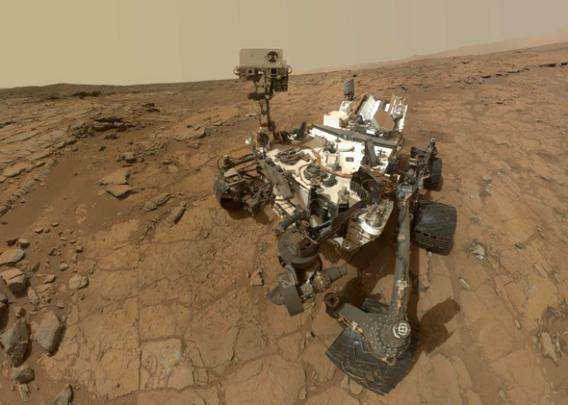

But as humanity’s technical prowess gained on our insatiable curiosity, something strange happened. It was no longer necessary to go places, dragging our corporal beings around, with their demands for oxygen, water, and an inconsiderately narrow temperature range. Instead, we could send robots to do the work, beaming back streams of 1s and 0s, seeing new vistas for us, enduring environmental hazards without complaint. And the digital spoils have been stunning: The Kepler spacecraft discovered more than 3,500 putative new worlds in four years. The Hubble Space Telescope peered 12 billion years back in time to the early stages of the universe. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter can spot rocks the size of a dinner plate on the surface of the Red Planet.

Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech

Exploration is, most certainly, not dead. On the contrary, more of the universe is open for our perusal than ever before, and the data deluge only continues to grow, a veritable Moore’s Law of curiosity-driven knowledge.

But is this modern, screen-mediated form of exploration recognizable as the same enterprise that led our ancestors to the ends of the Earth with poetry on their lips?

Historically, our first knowledge of a place (What plants grow here? Is there gold? Any savages in need of salvation?) has been coincident with our first feeling of it (Why does the light look different here? Why is it so hard to breathe at this altitude? Are these blood-sucking insects bad?), intimately linked with a humanistic, highly personalized quest for self-realization (What has my suffering taught me about the human condition? What are the limits of my abilities?). This cocktail of intellectual, sensory, and emotional discovery infused the ventures with an intoxicating blend of novelty: This was life at its most essential, a distillation of our caveman roots and hardwired wanderlust.

But the future of exploration will be different: From here on out, our first experiences of new places will be virtual, not physical. By the time the first person walks on Mars, we will know every pebble of the landing site. The subsurface contours of new caves may be mapped by ground-penetrating radar or acoustic backscatter. New oceanographic environments will first be seen through the cameras of a remotely operated vehicle, as scientists watch from a shipping container on a boat.

We’ve entered a fundamentally new realm of exploration, one that divorces the intellectual jolt of new knowledge from the visceral thrill and personal fulfillment of self-transportation to new places.

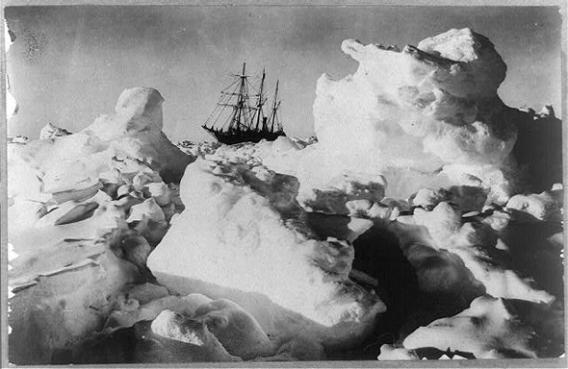

This new paradigm cuts the cord that has historically linked adventure and exploration. In centuries past, fitness, strength, and endurance were competitive advantages in attaining new knowledge. If you could brave the whitecaps of the Southern Ocean and the mind-numbing Antarctic gales, then you had a scoop: all kinds of waddling flightless birds, for example, new to the realm of human knowledge.

Courtesy of Underwood & Underwood/Library of Congress

Today, barriers to new knowledge are technical, not physical; we’re limited not by food supplies and warm clothing, but by propulsive constraints and interplanetary bandwidth, making athletic daredevils less integral to the acquisition of new scientific samples. As a result, adventurers and explorers pursue different goals with distinct tools and incentives.

Modern-day adventurers—glorified stuntmen, some would argue—are in a constant race of one-upsmanship, collecting superlatives in an attempt to climb mountains faster or scale rock faces with less equipment. These daredevils are often remarkable athletes, but their contribution of new knowledge is minimal; their aim is corporate sponsorships, traded for with the professional currency of “extremeness.” Our front-line explorers, like the scientists and engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who operate dozens of missions examining the far reaches of outer space, need not be Herzog-esque physical specimens. Mohawk-ed though they may be, carpal tunnel is the most pernicious physical risk.

What do we lose—and gain—by this great divergence? Does it matter that exploration is no longer so linked with physical exertion and bodily risk? The benefits, perhaps, are easier to recognize. Billions of pixels’ worth of images, heat maps of the early universe, glimpses billions of years into the past. This information—and we’re far from converting even a small fraction of it into “knowledge”—holds the secrets to the laws of the universe and our place in the cosmos.

The negative consequences are harder to define, but equally real. Without embodied emissaries, our connectedness to the endeavor is compromised. As the physical reality of exploration becomes more similar to video games, we are less present, less participatory, and perhaps less emotionally invested. The human drama of exploration has inspired compelling storytelling, forming the backbone of man-vs.-nature narratives. Some of the most riveting contemplations on mortality have come from those who have hovered near its edge while plumbing the depths of endurance in pursuit of the new.

Robots lack the emotional heft of human explorers, and we lose some of the inspiration inherent in seeing fellow humans at their physical peak, similar to a transcendent athletic accomplishment or dance performance. A clear consequence of this void is the psychic need to anthropomorphize our robotic emissaries, as shown by first-person Mars rover Twitter accounts and, most adorably, by Wall-E’s emotive sensors.

Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Exploration is stronger than ever, but what of its spirit? We’re learning more about the universe and our place in it than at any other time in human history, but the new era of roboticized exploration changes our relationship with our surroundings; there are emotional and philosophical losses that accompany this new paradigm.

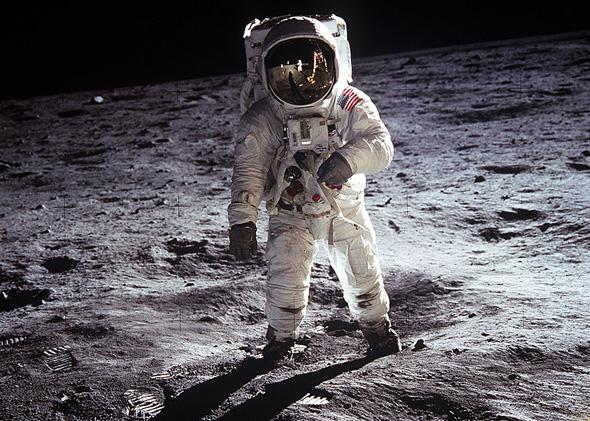

Consider this: The photograph of Buzz Aldrin on the moon, boots planted firmly in the gray dust of another celestial body, is one of the most evocative signals of human progress and capability of the past century. But would this photograph, shorthand for the pinnacle of exploratory achievement, be just as affecting if there weren’t a gold-tinted visor staring back at you?

More from Slate’s series on the future of exploration: Is the ocean the real final frontier, or is manned sea exploration dead? Why are the best meteorites found in Antarctica? Can humans reproduce on interstellar journeys? Why are we still looking for Atlantis? Why do we celebrate the discovery of new species but keep destroying their homes? Who will win the race to claim the melting Arctic—conservationists or profiteers? Why don’t travelers ditch Yelp and Google in favor of wandering? What can exploring Google’s Ngram Viewer teach us about history? How did a 1961 conference jump-start the serious search for extraterrestrial life? Why are liminal spaces—where urban areas meet nature—so beautiful?

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.