We’ve been to the moon and just about everywhere on Earth. So what’s left to discover? In September, Future Tense is publishing a series of articles in response to the question, “Is exploration dead?” Read more about modern-day exploration of the sea, space, land, and more unexpected areas.

Remember those wonderfully tactile and visual globes you’d spin in grade school? The rainbow-colored countries and the waist-belt equatorial line were as familiar as the big white spot at the globe’s top—the polar cap. As we moved from grade to grade, that constant fixture in the classroom—the globe—rarely changed. Maybe a border would shift here or there, or a new country like Serbia or Namibia would emerge, but the white spot at the top—the Arctic—always remained. Remote. Untouchable. Unalterable.

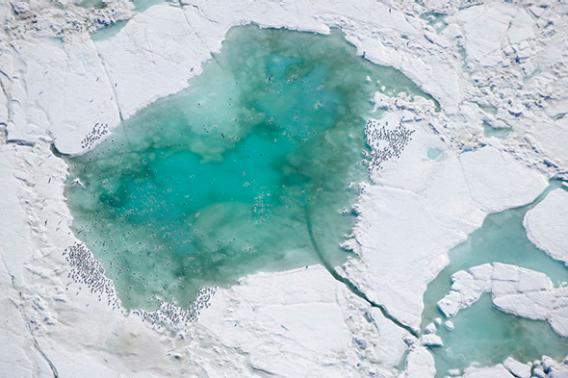

No longer. Thanks to the felling of forests and the spewing of carbon, a different map has materialized as the highest latitudes on Earth warm inexorably. Just when it seemed there was no place left to explore, the polar white veil has been pulled back to reveal virgin territory.

Scientists saw it coming. Explorers who forecast change through satellite images or capture the disappearance of glaciers on camera warned us that the massive ice sheets were melting. And in an increasingly warmer and more crowded world, we’ve come to accept this as fact. Moreover, the just released 2013 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report makes it clear (or at least should) to even the most fervent doubters that these changes are the fault of humans, of you and me. Yet what’s surprised even the elite academy of climate scientists is the shockingly fast pace at which it’s happening.

Tragically, and some 30 to 50 years before we expected, climate change is erasing the big white spot on top of the globe.

And the gold rush has begun.

Exploration isn’t dead here. In this newly accessible maritime realm, treasure maps are being created—X marks the spot of new shipping lanes, untold oil and gas reserves, lodes of rare precious metals, and potential tourism destinations. Like pirates of the colder meridians, big businesses and governments are swooping in to grab the booty from a virtually unclaimed and weakly regulated region. Meanwhile environmental groups are partnering with local communities, the fishing industry, and others to help them chart their own destinies in this fresh terrain, assuring protection for indigenous communities, local economies, and stunningly iconic wildlife like whales and walruses, polar bears and pelagic birds. This is the north’s new normal.

* * *

Photo courtesy of Florian Schulz

In the hull of a sailboat gliding through the Aleutian Islands, Florian Schulz is tossed about as if in a washing machine. The conservation photographer is cradling the body of his camera, laser-focused on the small LCD screen reviewing what he’s documented on the rolling seas amid the frigid salt spray. Florian represents a different kind of explorer.

He’s a unique breed of pioneer, exploring a world dramatically altered by climate change.

Florian, a partner with World Wildlife Fund (where I work as a senior director of conservation resources), is filming Arctic wildlife and the unnatural threats they now face in this uncharted territory—gray whales and natural gas, orcas and oil extraction, narwhals and shipping noise. Florian and WWF scientists are identifying the places that must remain undisturbed or be treated with great care.

And they’re searching for compelling stories that will shine a light on what’s at stake for a new set of decision makers and a generation unfamiliar with the “big white spot” on top of the classroom globe.

Florian’s chronicled not only the retreat of ice sheets, but the advance of shipping in the Arctic. Each year brings more ships—and more risk of irreparable spills—to the now navigable waters of the Arctic Ocean. No place tells this story better than Unimak Pass. The pass is an eye-of-the-needle bottleneck between islands in the Aleutian chain—a highly trafficked ocean corridor where migrating gray and humpback whales pass each spring and fall for points north and south. It’s also one of the most critical links along their migration route from the rich summer feeding grounds of the high Arctic to the wintering nurseries in Mexico where they’ll give birth and nurse their giant calves.

One of the oil developments at the edge of the Arctic Refuge in Alaska in the Canning River delta. Oil companies have pushed for opening the Arctic Refuge to the east of the Canning River for oil development.

Photo courtesy of Florian Schulz

The pass was already a tight squeeze for thousands of whales, but in today’s “new” Arctic, they must share it with the clamor of shipping noise that grows louder year after year. They must avoid the perils of collision with an increasing number of tankers, bulk carriers, and container ships. And along their migration route these marine giants must navigate blindly, unable to use their hearing effectively as the noise from ships and oil and gas exploration often masks their ability to hear their family, locate predators and find food.

Yes, the Arctic has become one of the last remaining explored places on Earth. But with the global population racing toward 9 billion and a rapidly warming the planet, perhaps exploration is more than just a swashbuckling discovery of the last untapped sea and land resources. Perhaps the greatest undiscovered frontier involves the search for solutions that will save the most pristine ecosystems on Earth, feed a hungry planet, and bring our consumption patterns back into balance with the natural world. This is the sort of explorer we desperately need.

Stepping off the sailboat onto terra firma, Florian and WWF scientists take their biological findings, observations of escalating threats, and their conversations with Inuit communities, into a veritable Anchorage war room. There, they’ll plot a collaborative course that will hopefully forge agreement among Arctic nations to balance new development with new levels of protection for the Arctic’s biologically diverse waters that are far from being a “great white nothingness.”

These are the explorers of the 21st century and sustainability is their frontier.

Photo courtesy of Florian Schulz

In the Arctic, these explorers are seeking innovative technologies to track and direct the passage of ships, whales and other marine fauna in an oceanic version of an air traffic control system. They are explorers finding cool, contemporary ways to raise awareness about climate change and the importance of the Arctic among a generation who will never know that polar bears once roamed this vast region, or that burgeoning fields of oil exploration now dotting the seascape were once the unspoiled, great white polar cap. And they are explorers searching for technological solutions to minimize bycatch of whales and threatened species in the nets of an Alaskan fishing industry that produces almost half of the seafood on your plate.

Yes, that big white spot will soon be much smaller. And the digital globe my kids now view on their iPads will look quite different. But if the future of exploration becomes as much about solving Earth’s problems as it is about searching Earth’s places, there’s hope.

If classic explorers could steer a boat across vast oceans, put a man on the moon, summit the world’s highest peaks or dive to its deepest depths, then surely a new breed of explorer can channel the same ingenuity to create a world where we both profit from and protect nature, and maybe even save a whale or two along the journey.

More from Slate’s series on the future of exploration: Is the ocean the real final frontier, or is manned sea exploration dead? Why are the best meteorites found in Antarctica? Can humans reproduce on interstellar journeys? Why are we still looking for Atlantis? Why do we celebrate the discovery of new species but keep destroying their homes? Why don’t travelers ditch Yelp and Google in favor of wandering? What can exploring Google’s Ngram Viewer teach us about history? How did a 1961 conference jump-start the serious search for extraterrestrial life? Why are liminal spaces—where urban areas meet nature—so beautiful?

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.