We’ve been to the moon and just about everywhere on Earth. So what’s left to discover? In September, Future Tense is publishing a series of articles in response to the question, “Is exploration dead?” Read more about modern-day exploration of the sea, space, land, and more unexpected areas.

We shall not cease from exploration

and the end of our exploring

shall be to return where we started

and know the place for the first time

That tidbit of T.S. Eliot is stolen from Graham Hawkes, a submarine designer who really, really loves the ocean. Hawkes is famous for hollering, “Your rockets are pointed in the wrong goddamn direction!” at anyone who suggests that space is the Final Frontier. The deep sea, he contends, is where we should be headed: The unexplored oceans hold mysteries more compelling, environments more challenging, and life-forms more bizarre than anything the vacuum of space has to offer. Plus, it’s cheaper to go down than up. (You can watch his appealingly arrogant TED talk on the subject here.

Is Hawkes right? Should we all be crawling back into the seas from which we came? Ocean exploration is certainly the underdog, so to speak, in the sea vs. space face-off. There’s no doubt that the general public considers space the sexier realm. The occasional James Cameron joint aside, there’s much more cultural celebration of space travel, exploration, and colonization than there is of equivalent underwater adventures. In a celebrity death match between Captain Kirk and Jacques Cousteau, Kirk is going to kick butt every time.

In fact, the rivalry can feel a bit lopsided—the chess club may consider the football program a competitor for funds and attention, but the jocks aren’t losing much sleep over the price of pawns and cheerleaders rarely turn out for chess tournaments. But somehow the debate rages on in dorm rooms, congressional committee rooms, and Internet chat rooms.

Damp ocean boosters often aim to borrow from the rocket-fueled glamour of space. Submersible entrepreneur Marin Bek talks a big game when he says, “We can go to Mars, but the deep ocean really is our final frontier,” but he giggles when a reporter calls him the “Elon Musk of the deep sea,” an allusion to the founder of the for-profit company Space X who is rumored to be the real-life model for Iron Man’s Tony Stark.*

Even Hawkes admits that he “grew up dreaming of aircraft”—though he means planes, not spaceships—but “then I got to look at this subsea stuff and I saw this is where aviation was all those years ago. The whole field was completely backwards, and that’s why I jumped in.”

Image courtesy of NASA

While many of the technologies for space and sky are the similar, right down to the goofy suits with bubble heads—the main difference is that in space, you’re looking to keep pressure inside your vehicle and underwater you’re looking to keep pressure out—there’s often a sense that that sea and space are competitors rather than compadres.

They needn’t be, says Guillermo Söhnlein, a man who straddles both realms. Söhnlein is a serial space entrepreneur and the founder of the Space Angels Network. (Disclosure: My husband’s a member.) The network funds startups aimed for the stars, but his most recent venture is Blue Marble Exploration, which organizes expeditions in manned submersibles to exotic underwater locales. (Further disclosure: I have made a very small investment in Blue Marble, but am fiscally neutral in the sea vs. space fight, since I have a similar amount riding on a space company, Planetary Resources.)

As usual, the fight probably comes down to money. The typical American believes that NASA is eating up a significant portion of the federal budget (one 2007 poll found that respondents pinned that figure at one-quarter of the federal budget), but the space agency is actually nibbling at a Jenny Craig–sized portion of the pie. At about $17 billion, government-funded space exploration accounts for about 0.5 percent of the federal budget. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—NASA’s soggy counterpart—gets much less, a bit more than $5 billion for a portfolio that, as the name suggests, is more diverse.

But the way Söhnlein tells the story, this zero sum mind-set is the result of a relatively recent historical quirk: For most of the history of human exploration, private funding was the order of the day. Even some of the most famous examples of state-backed exploration—Christopher Columbus’ long petitioning of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, for instance, or Sir Edmund Hillary’s quest to climb to the top of Everest—were actually funded primarily by private investors or nonprofits.

But that changed with the Cold War, when the race to the moon was fueled by government money and gushers of defense spending wound up channeled into submarine development and other oceangoing tech.

“That does lead to an either/or mentality. That federal money is taxpayer money which has to be accounted for, and it is a finite pool that you have to draw from against competing needs, against health care, science, welfare,” says Söhnlein. “In the last 10 to 15 years, we are seeing a renaissance of private finding of exploration ventures. On the space side we call it New Space, on the ocean side we have similar ventures.” And the austerity of the current moment doesn’t hurt. “The private sector is stepping up as public falls down. We’re really returning to the way it always was.”

And when it’s private dough, the whole thing stops being a competition. Instead, it depends on what individuals with deep pockets are pumped about—or what makes for a good sell on a crowdfunding site like Kickstarter.

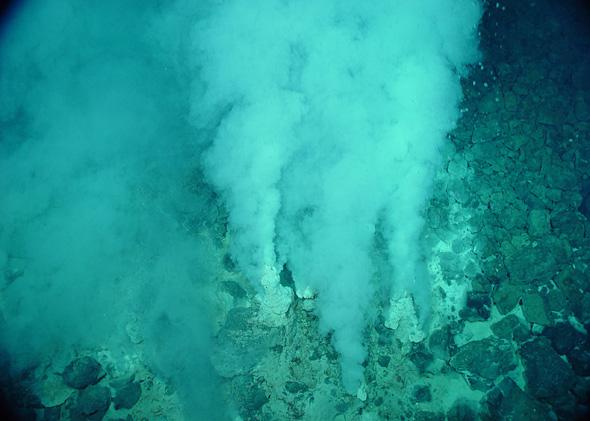

Looking for alien life forms? You probably think you’re a natural space nerd, but you’re wrong. If the eternal popularity of “Is There Life on Mars?” stories is any indication, an awful lot of people are just hoping for some company. We really have no idea what’s hanging out at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, but there are solid reasons to think the prospects for biological novelty (and perhaps even companionship for humanity) are better down there than they are in Mars’ Valles Marineris.

Want a fallback plan for when that final environmental catastrophe occurs? Underwater or floating habitats may offer fewer challenges than space colonies if you’re looking to quickly build a self-sustaining place to live when things cool down, warm up, dry out, or otherwise return to fitness for human habitation.

If you’re just looking for wide open spaces, the vastness of space may ultimately prove your final frontier, but Söhnlein has a very human take on the question: “For myself,” he says, “I’d probably go with the oceans. Humanity has millennia to explore the cosmos. But I have only decades or—depending on who you believe—centuries. And there’s plenty to discover down there to fill my lifetime.”

More from Slate’s series on the future of exploration: Is manned sea exploration dead? Why are the best meteorites found in Antarctica? Can humans reproduce on interstellar journeys? Why are we still looking for Atlantis? Why do we celebrate the discovery of new species but keep destroying their homes? Who will win the race to claim the melting Arctic—conservationists or profiteers? Why don’t travelers ditch Yelp and Google in favor of wandering? What can exploring Google’s Ngram Viewer teach us about history? How did a 1961 conference jump-start the serious search for extraterrestrial life?

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.

*Correction, Feb. 9, 2016: This piece originally misspelled the last name of Marin Bek. (Return.)