How Does a Comic Book Letterer Work?

Deron Bennett explains the art and craft behind placing word balloons and sound effects in a Batman story.

Deron Bennett

This season on Working, we’re talking to the people who make Batman comics, leading you through the artistic production process.

For this week’s episode, which you can listen to via the player above, we spoke with letterer Deron Bennett.

“Any of the text that you’re seeing on a comic books page is the responsibility of the letterer,” Bennett says. “So, all the cool sound effects—the boom pows and all that stuff—that’s also the responsibility of the letterer, as well as the placement of the word balloons and all the dialogue that’s in there.”

There are only a handful of celebrity letterers in the comics business. “You get more recognition within the industry than from the fandom,” Bennett says. Still, he suggests that it’s important for letterers to try to “show what they do, as opposed to letting it just be there. We want to let you know that there’s an artist, there’s a person responsible for this part of the comic.”

Though their work is essential to the look and feel of a book, it also tends to disappear into the page itself. Call it the letterer’s paradox: If they do their job right, you can almost forget they did it at all. When characters speak, you hear them talking in their own voices. When a punch lands with an audible “crack,” you feel it land. As Bennett puts it, “We’re bringing something to help tell that story, to help guide the reader through the book.”

Originally, Bennett hoped to be an animator, and later a writer. Ultimately, he grew to love comics, since they brought together his passions for writing and drawing. In particular, he cites the importance of Milestone Comics, a publisher that sought to increase the representation of minorities in the medium. Pursuing a career in the business, he went on to study sequential art at the Savannah College of Art and Design.

Drawing on that education, he found work early in his career with Tokyopop, helping to “localize” Japanese manga. Initially, he says, “I thought of it as a stepping stone into something greater—drawing and writing—but I found that I actually liked it.” He began to see hand-drawn sound effects and the other details he was laboring over as “a new artistic puzzle that I could delve into. Typography started becoming something more integrated into my life.”

Today, Bennett runs a lettering studio that contributes to fortysomething books a month. Accordingly, though Bennett played an important role in the Batman narratives that we’ve been discussing throughout this series, he also contributes to many other projects, rarely spending more than five hours on a given issue. “Lettering is basically a game of volume,” he says. “Whereas a penciler might be working on one single book, we have to work on multiple books at the same time in order to be successful.”

Past generations of letterers would often cut out word bubbles and paste them on a page. By contrast, Bennett, like many of his peers, operates almost exclusively on a computer, with the help of a Wacom tablet. The programs he uses, however, depend on the assignment: For translations of manga, he employs Adobe InDesign, which is, he says, “catered more toward layout,” making it easier to drop text into existing word balloons. But with Western comics, where he has the opportunity to be “a little more creative,” he uses Adobe Illustrator, since it allows him more freedom to implement his own choices and ideas.

Though the process may seem industrial, Bennett argues that there’s much more to what he does. “What a lot of people don’t realize is that lettering is a form of art like any other. I liken it to graphic design more than anything else,” he says. “You’re playing with principles like shape … contrast, spatial relations, white space, negative space.”

Sometimes, Bennett just has the script and the art to guide him, but on other occasions he’ll be in conversation with the rest of the creative team as he works. “When they let me know their vision, that helps to inform my ideas,” Bennett says. “But for the most part, it’s just an isolated thing, where the communication is facilitated through the editor. They’ll be my main point of contact.”

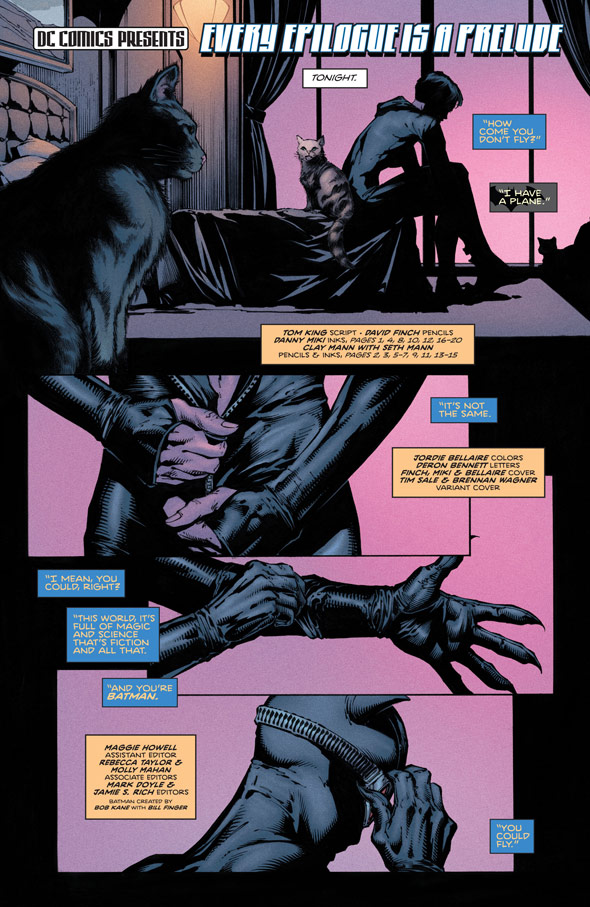

Bennett claims he makes his own choices in response to what the artist has given him. If the lines are sharply defined, his word balloons probably will be too, for example. Similarly, when lettering the art of a penciler such as David Finch, whose work can be seen above, he’ll sometimes place the balloons over the panel gutters as well, seeking to amplify the design of the page itself. But he also stresses that part of his job is about staying out of the way. “For the most part I try to stay out of the art,” he says. “I make sure I’m trying not to cover the action, or even the quiet moments, because you really want to let that part breathe. The role of the letterer is secondary or tertiary, where you’re just there to support what’s already there.”

Though Bennett has lettered a wide range of beloved properties—including He-Man, one of his childhood favorites—he takes special professional pleasure from his efforts on Batman. “Working on Batman is fun because … it’s more so than other books a lesson in designing word balloons, designing the page,” he says. He adds that he was particularly focused on that issue while working on Tom King’s Batman proposal story. On one two-page section of the issue, for example, he established “a sort of semicircle of the word balloons across the pages,” seeking to create “rhythmic lines to use the balloons to shape the page.”

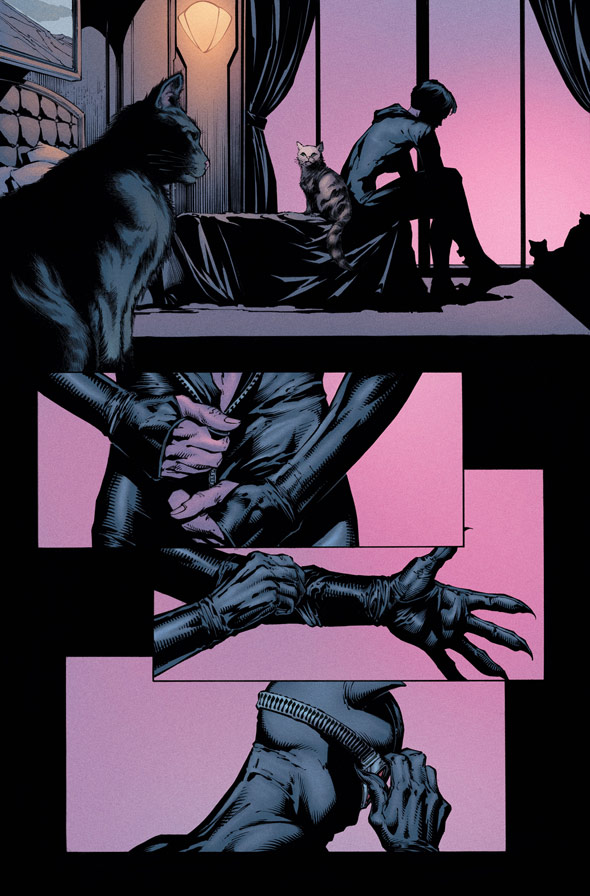

Speaking of another section in the issue drawn by Clay and Seth Mann, which you can see above, he says it was important to work within the “curvilinear perspective” of the design. As he remembers, “I wanted to let that breathe as much as possible, but I wanted to follow that shape.” In that spirit, he incorporated curved tails on the word balloon instead of having them point straight at the characters, the better to “follow that perspective.”

But if Batman is an exciting professional responsibility for Bennett, there’s also the pleasure he takes in helping to tell the stories of such a long-lived character. Not long ago, his daughter, who rarely shows interest in his work, asked him if he knew that Batman had proposed to Catwoman. “I opened up my page where I lettered him on his knees, and was like, Wow! You did that? It was a highlight for me,” he says. “Being part of this culture. It’s just so fun. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”