How Does a Batman Comic Book Writer Work?

Tom King shares how he composes a Batman script and explains how he ended up telling the character’s stories.

Listen & Subscribe

Choose your preferred player:

Get Your Slate Plus Podcast

If you can't access your feeds, please contact customer support.

Listen on your computer:

Apple Podcasts will only work on MacOS operating systems since Catalina. We do not support Android apps on desktop at this time.

Listen on your device:RECOMMENDED

These links will only work if you're on the device you listen to podcasts on.

Set up manually:

Episode Notes

This season on Working, we’re talking to the people who make Batman comics, leading you through the process from initial scripting to fully finished art.

In a recent installment of his eponymous comic book series, Batman gets down on one knee and asks Catwoman to marry him. For all the surrounding drama, it’s an almost subdued moment. And though the issue ends on a cliffhanger—readers still don’t know whether she said yes—that uncertainty feels like a reflection of the fraught history that these two characters share.

As the issue’s writer, Tom King, tells it in this episode of Working, which you can listen to via the player above, simply getting permission to tell that story was difficult. Batman may have been born on the pages of Detective Comics in the late 1930s, but today he’s a multibillion-dollar property. That means any one writer can only do so much with the character and his world. Thus, quiet as that proposal story may have been, King still had to get approval from his bosses, who had to get approval from their own bosses and so on up the corporate chain of command.

It’s an experience that’s presumably familiar to King, who took an unusual path to comics. Though he grew up a self-professed nerd—unable to “throw a ball in a hoop or run using my legs”—and interned at Marvel Comics, his life took a turn after the Sept. 11 attacks. Wanting to do something, he joined the CIA and served in Iraq as a counterterrorism-focused case officer. Ultimately, it was his family that pulled him back. He had, he tells us, grown up without a father, and he wanted his own children to have a different experience.

Both of those personal trajectories—his espionage background and his longing for a more stable family life—would shape the comics he began to write after returning to domestic life. His series The Sheriff of Babylon, for example, draws on his experiences with the CIA, and his award-winning The Vision finds a superhero grappling with the pressures of paternity. The two threads intertwine even more closely in his run on Batman, which has been as much a meditation on the vagaries of family as it is a story about sneaking up on people and punching them.

Describing how he thinks about writing, King observes, “All stories are just stories of a character changing.” And yet, where Batman is concerned, you can only ever change so much, partly because the assignment of writing his adventures is surprisingly intimidating. As a more established writer told King early on, virtually every Batman story imaginable has been told at some point in the character’s history, and more will be told down the line. “The best lesson to learn in comics, and probably any serialized medium,” King says he eventually realized, “is that the next guy who gets it is going to erase everything you did.”

It’s important, King claims, to let go of those worries, because, as he’s working, he has to focus on his more immediate collaborators—the teams of artists who bring his scripts to life. As a writer, he’s just the first step in the production chain that finds others—many of whom we’ll be interviewing in the episodes ahead—penciling, inking, coloring, and lettering his stories.

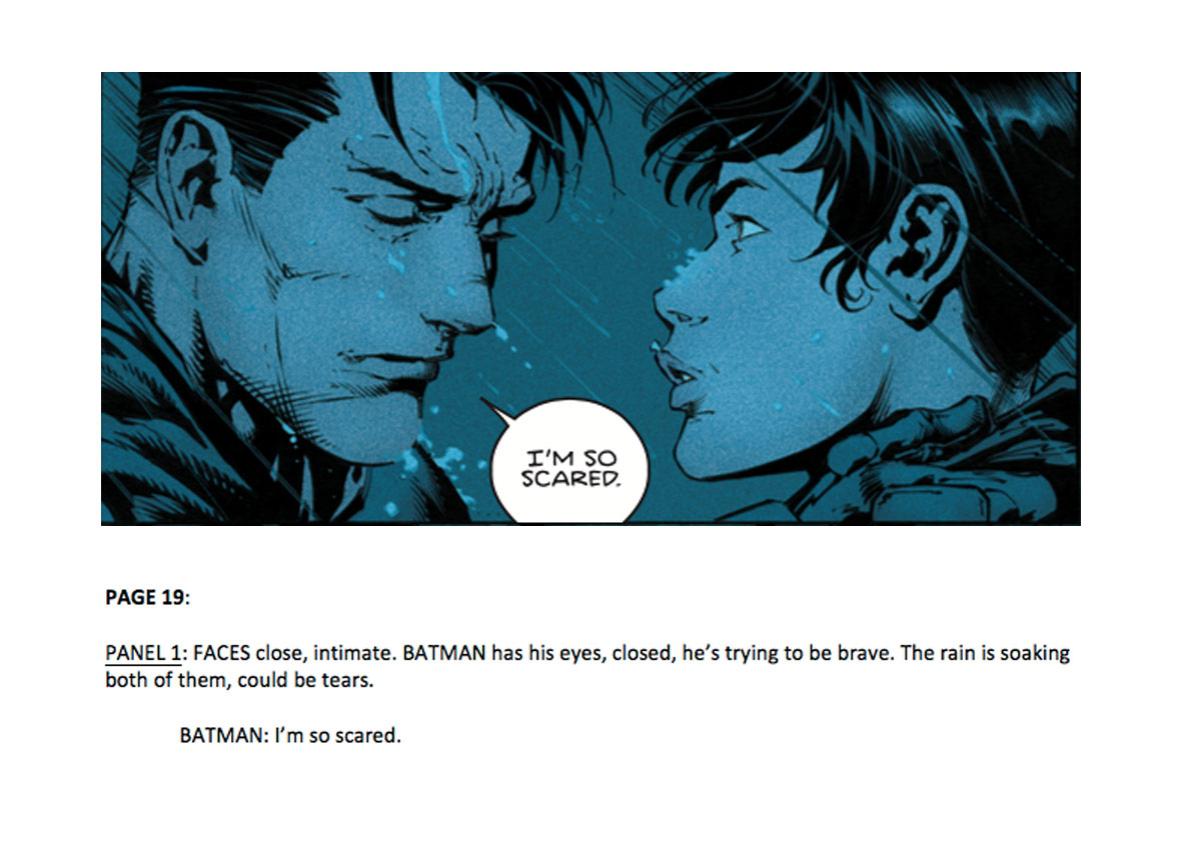

King claims that he rarely outlines, proceeding on the assumption that what he forgets wasn’t worth remembering in the first place. He writes at a steady pace—trying to turn out five script pages a day—but the amount of detail he includes in his scripts varies depending on which artist he’s writing for. The description of one panel leading up to Batman’s proposal, for example, simply reads, “FACES close, intimate. BATMAN has his eyes, closed, he’s trying to be brave. The rain is soaking both of them, could be tears.” That simplicity is a sign of his comfort with, and trust in, the work of his penciler, David Finch, who we’ll be chatting with in our next episode.

His familiarity with his collaborators also shapes the content of his stories more directly. When he was working on the proposal issue, for example, King was concerned that Finch, a dynamic artist who delights in spectacular images, would be frustrated at the prospect of drawing a book in which no one took a fist to the jaw. (Finch, for what it’s worth, claims in our next episode that he didn’t mind.) In general, King also leaves other elements to the artists’ imaginations: While he describes what should be happening in each panel, for example, he typically doesn’t dictate how those panels should be laid out on the page, leaving such decisions—which can have an important effect on the way we experience comic book stories—to Finch and others.

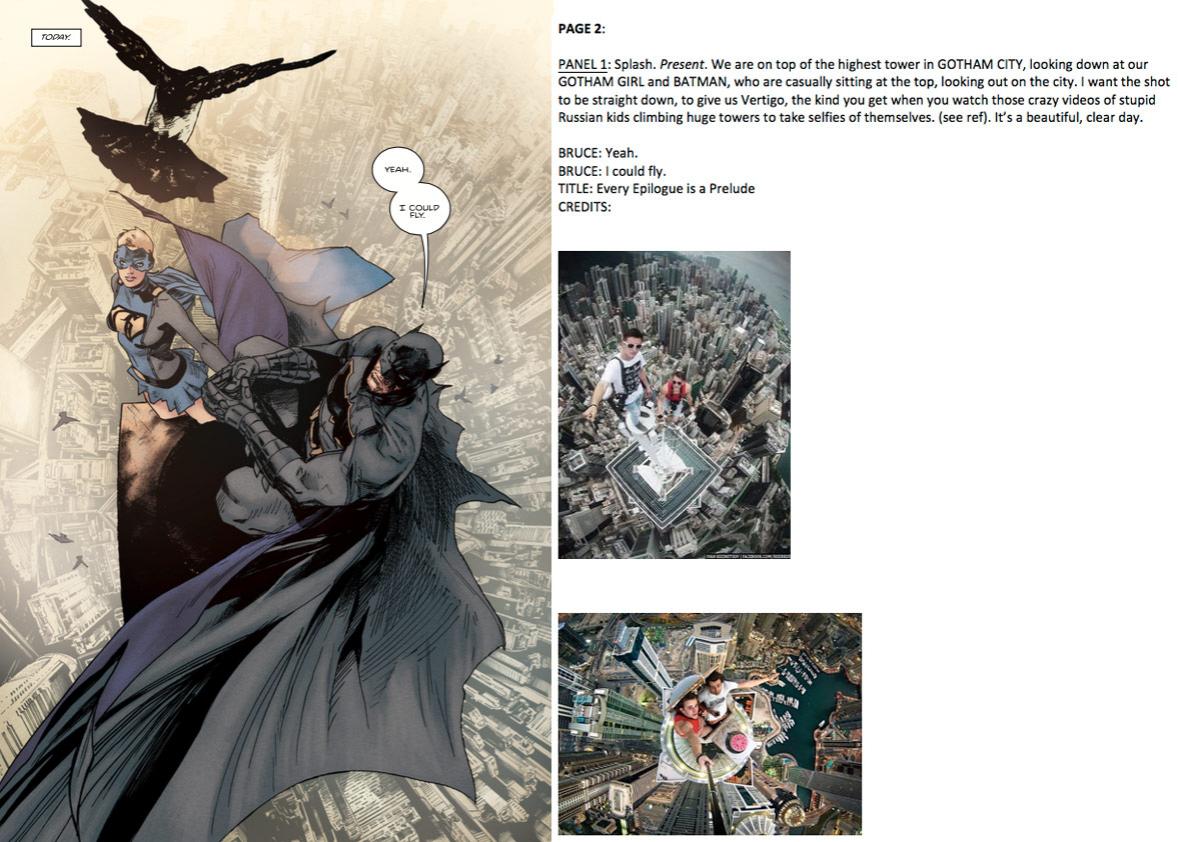

In some cases, though, King also provides visual references for the artists working on a book. Those images, which he embeds directly in his text documents, are usually photographs that he’s found somewhere on the internet, since he doesn’t really draw. On one page from the proposal issue, for example, he wanted a picture that would give readers vertigo of “the kind you get when you watch those crazy videos of stupid Russian kids climbing huge towers to take selfies of themselves.” To help drive that point home for brothers Clay and Seth Mann, who would be illustrating the page, he provided two accompanying photographs.

Sometimes King will talk with his collaborators as they work, though there, too, he tailors his approach to them. With some, he says, he’ll chat on the phone, and with others, he simply exchanges direct messages on Twitter. As finished pages come back from the artists—a process we’ll be exploring in much more details soon—King does have the opportunity to review their efforts, but he claims he tries not to interfere too much. “You have to trust your artists,” he says.

For King, then, writing Batman well is at least partly about knowing when to cede control: when to fall back on the character’s history, when to let the artists step in and do their jobs. But that doesn’t mean he cuts himself out of the process. “What eventually you find in comics,” King says, “is the only thing unique you can bring to a character who’s been around for 80 years is yourself.”

Then, in a Slate Plus extra, we let Slate staffers ask King their most pressing questions about Batman and his world. If you’re a member, enjoy bonus segments and interview transcripts from Working, plus other great podcast exclusives. Start your two-week free trial at slate.com/workingplus.