Never Goldwater

The attempt to wrest the 1964 GOP nomination from the Arizona senator and the birth of the modern GOP.

AP Images

This article is adapted from Whistlestop: My Favorite Stories From Presidential Campaign History.

Rocky Go Home

On July 14, 1964, Nelson Rockefeller stepped to the podium at the Republican National Convention to get abused. It was nearly 10 p.m. Convention managers made sure to delay the proceedings as long as they could to deprive him of a satisfyingly large television audience. But if only a modest number of people were watching at home, all eyes were on him in the hall.

Rockefeller, who would famously give a protester his middle finger as Gerald Ford’s vice president in 1976, might as well have been doing the same to this audience. His jaw was clenched as the jeers echoed off the walls of the Cow Palace, an aging Quonset-like structure outside San Francisco. The audience supported conservative Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, the all-but-certain nominee, and viewed Rockefeller, with his fondness for glossy art magazines, as the sneering embodiment of the Eastern establishment, which looked down at conservatives like Goldwater and his followers as unwashed ignoramuses. Rockefeller had competed against Goldwater in the primaries, labeling his followers kooks and declining to mask his contempt for their movement.

The clash had played out most severely in the California primary. Rockefeller campaigned against Goldwater’s “reckless belligerence” on foreign policy. Two weeks before the vote, Rockefeller, up 13 points in the polls, had sent a mailer to California voters asking, “Who do you want in the room with the H Bomb button?”

Just days before the primary, however, Rockefeller’s new wife gave birth to their first child. This reminded everyone that he once had an incumbent wife whom he divorced in order to marry the challenger. She was 18 years his junior and competed with him for scandal, in that she was married with four children at the time of their affair. William Loeb, the publisher of the influential Manchester, New Hampshire, Union Leader had called Rockefeller a “wife swapper.” Goldwater fans asked during the primary: “Do you want a Leader or a Lover in the White House?”i

Rockefeller lost in California, and now that he was back in the state months later, he was getting it from both sides. Two days before, as the GOP convention was starting, Rockefeller had been heckled while addressing 25,000 civil rights marchers (including baseball great Jackie Robinson) who had gathered on Market Street in San Francisco to protest Goldwater. When he promised a strong civil rights plank in the GOP platform, they responded,ii “Too late, too late.” “We want Johnson!” they yelled. It was the classic fate of the middle-of-the-road candidate: not just to be reviled, but to be associated with the extremists he opposed.

Convention organizers had only given the vanquished Rockefeller five minutes to speak to the convention, but his remarks were a concentrated blast against the extremism and racism he said were ruining the party. “These are people who have nothing in common with Americanism,” said Rockefeller, standing beneath a portrait of Abraham Lincoln. “The Republican Party must repudiate these people.”

The crowd booed. “We want Barry!” they chanted. Then the noisemakers picked up. The Rockefeller haters blew squeeze-horns and toy trumpets and hooters. Someone pounded a giant bass drum. Those with cowbells got busy.iii

Rockefeller couldn’t be heard and stopped talking. Goldwaterites seated in the rafters shouted themselves hoarse. Organizers, who were all in the Goldwater camp, reminded the speaker that he had a time limit. “You control the audience, and I’ll make mine five minutes,” he snapped. He was exhausted, having been kept up the night before by prank phone calls to his hotel room.

His remarks were interrupted 22 times in five minutes. “This is still a free country, ladies and gentlemen,” Rockefeller said, condemning “infiltration and takeover of established political parties by communist and Nazi methods.”

“It was as if Rockefeller were poking with a long lance and prodding a den of hungry lions,” wrote Theodore White in Making of the President.iv “They roared back at him.”

It was a contentious moment that marked the last shot fired in a monthslong losing battle to stop Goldwater from winning the Republican nomination. The immediate stakes for Rockefeller’s speech were not high. By the time he gave it, he and his allies had already been defeated but the ferocity of the exchange highlighted how passionate both sides still felt. The bitterness would last for years.

Bettmann/Getty Images

The audience was angered afresh because Rockefeller sounded like a Democrat, casting them as the villains in the national morality play. If you held a different view than he did—particularly on civil rights—you were a racist or extremist. Or, at the very least, you were giving comfort to people with those views.

Two nights later, Goldwater answered Rockefeller’s charge in his acceptance speech. “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” he said to roars of approval so loud they overwhelmed the capacity of the microphone, making it crackle. “And let me remind you also, that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.”

This is what a real party fight looks like: When people stand up at a candidate’s nominating convention and denounce the forces that allowed the candidate to win the nomination, and the candidate fires back with a defense rooted in the country’s foundational ideals. The Republican Party conventions of 1952 and 1976 were cliffhangers, but they can’t match the 1964 GOP convention for the melting heat of its ideological combat. The fight to stop Barry Goldwater was about first principles and values, not just tactical disputes about how to use a party’s power. In the 2016 campaign, Republicans unhappy with Donald Trump started a #NeverTrump movement and it failed just as spectacularly. This week the talk is about GOP unity, but the fights of 1964 proved that blunt exchanges over deeply held views—about the size of government, the threats to liberty, the protection of rights, and the security of a nation—can sharpen what parties and their leaders believe in. Elections are a time for choosing more than just a candidate.

The last time the Republican Party visited the Cow Palace, originally built to host a livestock convention, was in 1956 for Eisenhower’s second nomination. Before Eisenhower, Ulysses S. Grant was the last Republican president to have gone on to serve a second term. The ’56 convention was, at the time, the high point for the modern GOP, and a high-water mark of comity. At the Cow Palace in 1964, the crowd was in a raucous mood and rushing in an entirely different direction.

The Republican Party of 1964 had clear left and right wings in a form that would be unrecognizable today. Previous nominees had quickly worked to sew up the divisions and preached unity. In 1960, Goldwater himself had been a part of that unity effort, telling his allies on the right to “grow up” and work for the nominee, Nixon.v “If we want to take this party back—and I think we can someday—let’s go to work,” he said. In 1964 though, Goldwater was sounding a call to arms. It was fine with him if the moderates jumped in a lake.

Twice since the New Deal, moderates had nominated New York Gov. Thomas Dewey and twice he had lost, once to FDR and once to Truman. Conservatives were fed up with candidates who didn’t give voters a clear break with New Deal Democratic rule. In 1952, conservatives fell in love with Robert Taft but Eisenhower interrupted their dreams and gave moderates eight years in the White House.

For conservatives, Eisenhower’s victories had come at the cost of principle. The National Review, the organ of the movement, opposed Eisenhower and his move toward centrism. Its publisher, William Rusher, said that “modern American conservatism largely organized itself during, and in opposition to, the Eisenhower Administration.” Goldwater called the Eisenhower administration a “dime-store New Deal.”

As if to punctuate the point, when Eisenhower stopped in Amarillo, Texas, on the way to the ’64 convention, two young men hurled a Goldwater sign in a fit of enthusiasm. They were not aiming at the ex-president but hit him nevertheless, causing him to double over.vi

Moderate Republicans like Rockefeller supported the national consensus toward advancing civil rights by promoting national legislation to protect the vote, employment, housing, and other elements of the American promise denied to blacks. They sought to contain communism, not eradicate it, and they had faith that the government could be a force for good if it were circumscribed and run efficiently. They believed in experts and belittled the Goldwater approach, which held that complex problems could be solved merely by the application of common sense. It was not a plus to the Rockefeller camp that Goldwater had publicly admitted, “You know, I haven’t got a really first-class brain.”vii Politically, moderates believed that these positions would preserve the Republican Party in a changing America.

Conservatives wanted to restrict government from meddling in private enterprise and the free exercise of liberty. They thought bipartisanship and compromise were leading to collectivism and fiscal irresponsibility. On national security, Goldwater and his allies felt Eisenhower had been barely fighting the communists, and that the Soviets were gobbling up territory across the globe. At one point, Goldwater appeared to muse about dropping a low-yield nuclear bomb on the Chinese supply lines in Vietnam, though it may have been more a press misunderstanding than his actual view.viii

Conservatives believed that by promoting these ideas, they were not just saving a party—they were rescuing the American experiment. Politically, they saw in Goldwater a chance to break the stranglehold of the Eastern moneyed interests. If a candidate could raise money and build an organization without being beholden to the Eastern power brokers, then such a candidate could finally represent the interests of authentic Americans, the silent majority that made the country an exceptional one.

Goldwater looked like the leader of a party that was moving west. His head seemed fashioned from sandstone. An Air Force pilot, his skin was taut, as though he’d always left the window open on his plane. He would not be mistaken for an East Coast banker.

The likely nominee disagreed most violently with moderates over the issue of federal protections for the rights of black Americans. In June, a month before the convention, the Senate had voted on the Civil Rights Act. Twenty-seven of 33 Republicans voted for the legislation. Goldwater was one of the six who did not, arguing that the law was unconstitutional. “The structure of the federal system, with its 50 separate state units, has long permitted this nation to nourish local differences, even local cultures,” wrote Goldwater in Where I Stand.

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

Though Goldwater had voted for previous civil rights legislation and had founded the Arizona Air National Guard as a racially integrated unit, moderates rejected his reasoning. They said it was a disguise to cover his political appeal to anxious white voters whom he needed to win the primaries. He was courting not just Southern whites, but whites in the North and the Midwest who were worried about the speed of change in America and competition from newly empowered blacks.

The Stop Goldwater movement took real shape not long after he won the California primary on June 2. Goldwater’s opponents weren’t just worried that Goldwater’s hawkishness and scattershot positions—which seemed to shift from interview to interview—would lose him the presidency. They worried he would irreparably stain the party and hex Republicans also running for election that year.

Sen. Ken Keating of New York said he would not run as a Republican against Bobby Kennedy, but as an independent. Sen. Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania, who had been chairman of the Republican Party and had been a part of the successful Draft Eisenhower movement, said that if Goldwater were nominated, he’d bring 30 Republican members of Congress down with him that November.ix New York Sen. Jacob Javits, a moderate Republican, said that Goldwater’s victory would wrench the social order out of its sockets.

“The Republican establishment is desperate to defeat me,” Goldwater said. “They can’t stand having someone they can’t control.”

On June 7, a month before the GOP convention, 15 Republican governors sat at breakfast at the Cleveland Sheraton before a meeting of the National Governors Association. If anyone was going to stop Goldwater, it would be the governors. Historian Rick Perlstein explains why:

Republican governors were moderates because governing a state was a moderating job. It was they who were responsible for mass transit and hospitals and housing and job training ... It was they who would have to clean up the mess if a conservative White House were able to turn off their federal funding spigot. And it was they who would have to call out the National Guard should the civil rights revolution come to blows.x

Goldwater had the most delegates heading into the convention, but not enough to clinch the nomination, so a challenger could overtake him in San Francisco. The problem for the Republican governors was that no one would step forward and challenge Goldwater. Rockefeller was out. He’d tried during the primaries, but his loss in California and the bitterness from conservatives meant he could not make an appeal to the convention as a consensus candidate. He was used up by the process, familiar from overexposure. “The harder the candidates ran,” wrote Time that year, “the weaker they looked. The less the non-candidates ran, the better they looked.”xi

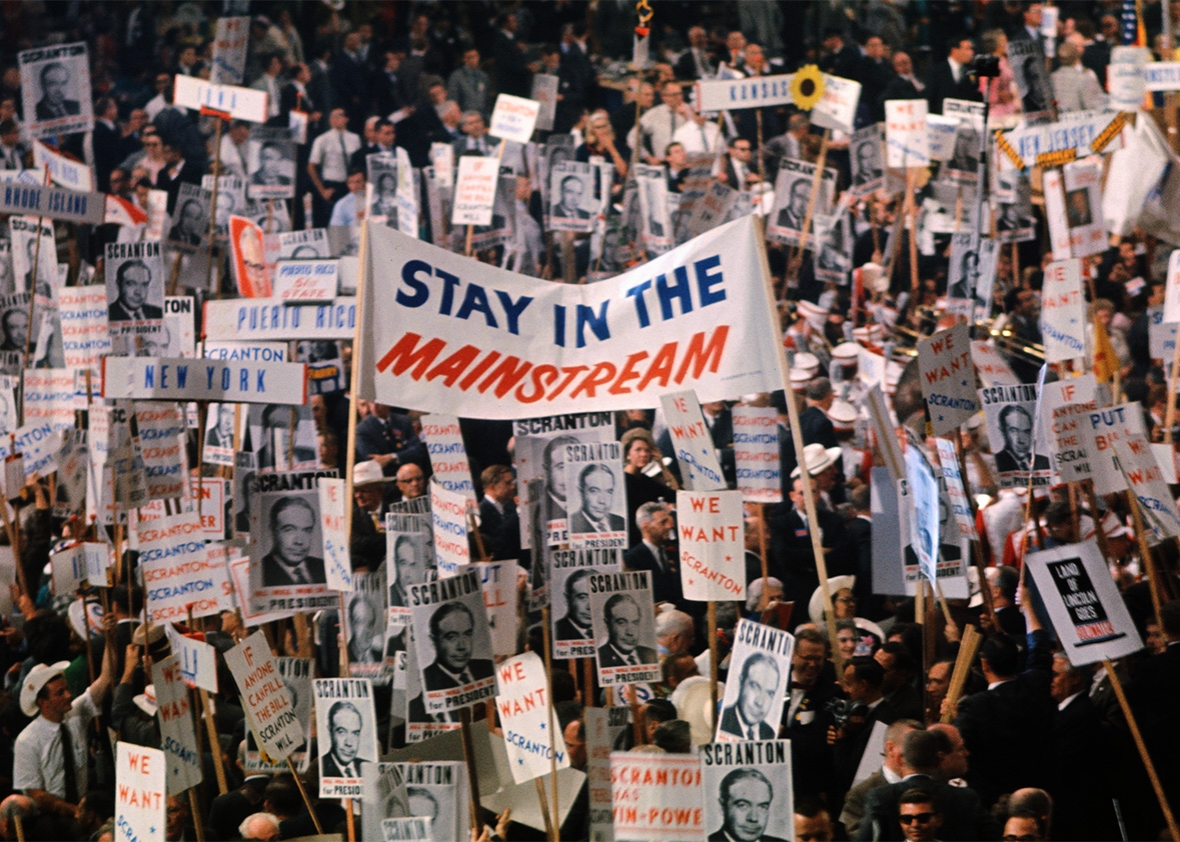

But one by one, the noncandidates decided to stay noncandidates: George Romney of Michigan had promised his constituents he’d stay out of the race. William Scranton of Pennsylvania set a date to announce his candidacy on CBS’s Face the Nation, but got cold feet when Eisenhower, who’d previously encouraged him, declined to publicly endorse an anti-Goldwater insurgency.

Richard Nixon arrived in Cleveland with his own plan to stop Goldwater. His loss in 1960 and subsequent exile had actually allowed the conservative movement to grow; because Nixon wasn’t the heir apparent to the nomination, Goldwater could rise. Nixon’s plan was to draft Romney, about which Romney was rightfully suspicious. The Michigan governor thought Nixon might be setting him up for a fall as a way to remove competition for a later run of his own. After a flurry of activity, which included a covert men’s room meeting between Romney and Nixon, the idea went nowhere.xii Without a candidate to take on Goldwater, Nixon nevertheless made a pitch for one at a press conference: “Looking to the future of the party, it would be a tragedy if Sen. Goldwater’s views, as previously stated, were not challenged and repudiated.”

By the end of the national governors’ meeting, no new hats were in the ring. Goldwater’s supporters saw their man acting with strength. The opposition, on the other hand, looked weak. “They didn’t unite,” wrote Roscoe Drummond in the Washington Post, who then reached into his metaphor basket. “They folded—like a crushed matchbox—under the Goldwater bandwagon.” Teddy White called the meeting at which there had been much activity but no progress “The Dance of the Elephants.”xiii

Richard Norton Smith, in his book about Nelson Rockefeller On His Own Terms, tells a story that captures the hollowness of the establishment movement. During the California primary, Rockefeller’s campaign manager Stu Spencer turned to the candidate and said, “Governor, I think it’s time to call in the Eastern Establishment.” To which Rockefeller responded, “You’re looking at it, buddy. I’m all that’s left.”

A week after the uneventful governors’ meeting and a month before the convention was to start, Gov. Scranton decided to jump in after all, telling a small group of aides after a long meeting at his home, “I am going to run.” It was a fairly bland statement, but a former Eisenhower aide now working with Scranton was swept up in the moment. Grabbing a blank paper from the coffee table, he wrote down the governor’s words and said, “I’m keeping this for my scrapbook.” It would ultimately be a thin volume.

Scranton had changed his mind, said aides, for three reasons: Goldwater’s vote to oppose the civil rights bill, which was cast days after the Cleveland governors’ meeting, the “rebellion” by Pennsylvania lawmakers in Harrisburg at the idea of a Goldwater nomination, and his fear that Goldwater would doom the entire party.xiv

“The nation, and indeed the world, waits to see if another proud political banner, which is our own, will falter, grow limp and collapse in the dust,” said Scranton to a frenzied audience at his announcement rally. “Has the Republican Party, a great many of our fellow citizens are asking, outlived its usefulness? Of course, the answer is no ... Lincoln would cry out in pain if we sold out our principles. But he would laugh out with scorn if we threw away an election.”

Scranton set out to woo delegates across the country. He carried a poll, commissioned by his campaign, that showed 62 percent of Republicans would vote for Johnson against Goldwater.xv He argued that Goldwater was talking nonsense off the top of his head and misunderstood how the American economy worked. Said Scranton, “The Republican Party wonders how it will make clear to the American people that it does not oppose Social Security, the United Nations, Human Rights and sane nuclear policy.”xvi It was no time, he said, “to go off half-cocked in the field of foreign policy.”xvii

Rockefeller threw his weight behind his colleague, but picking up delegates was not easy. Those supporting Goldwater were not budging. “I will vote for you if my vote alone is the only vote you obtain,” read one telegram sent to Goldwater. Another admirer said, “I give Barry my blood and the marrow from my bones.”xviii

Eugene Patterson of the Atlanta Constitution described the Goldwater legions as “[a] Federation of the fed-up dismayed by moral laxity, greed, the tax collector and the erosion of yesterday’s individualistic aspirational culture by social engineers and legislators masquerading as judges.”

This made it difficult for Scranton to court delegates.xix In Illinois, Scranton attempted to win the support of Everett Dirksen, the Senate majority leader, who had pushed the Republican senators to support the Civil Rights Act. Scranton asked Dirksen to run as a favorite-son candidate to lock up the state’s delegates—but he refused.xx The Senate leader predicted to the press the next day that Goldwater would be elected on the first ballot. When Scranton and Goldwater went to the Illinois caucus, Goldwater won 58 delegates. Scranton won none.

When Scranton arrived at the Cow Palace, his pickaxe broken from such fruitless prospecting, he was still fighting to keep the GOP from turning into “another name for some ultra-rightist society.”xxi The Stop Goldwater movement focused on making the case the Arizona senator would be a disaster for the party in the fall. Perhaps that would shake some delegates loose.

The competition was stiffer than it perhaps seemed. On the outside, the Goldwater operation had all the frantic boosterism that makes conventions so gaudy. Goldwater girls, dressed in sombreros and tasseled boots, flounced around while California delegates holding helium-filled, gold-colored balloons waved a large Bear Flag. The candidate had been furnished with a gold Cadillac for use during the week. In the Goldwater hospitality suite in the “Room of the Dons” at the Mark Hopkins hotel, 2,000 cases of an effervescent soft drink, gold in color and labeled “Goldwater,” was available thanks to a North Carolina soft drink manufacturer who had whipped it up for the occasion. “The right drink for the conservative taste,” it read on the green and gold can.

All this fun masked a stern Goldwater backroom operation. If you were traveling through the Mark Hopkins hotel you didn’t dare try to stop on Goldwater’s floor. If you did by mistake a thick-necked set of fellows would narrow their eyes at you and you’d know it was time to move on. Security was tight because both campaigns were at the same hotel, staying just a floor apart in a setup that had their offices and private quarters interlaced like layers on a cake. Security guards manned the elevators and the stairways. When Gov. Scranton’s wife tried to take the stairs to her husband’s office, she was stopped and not allowed to pass. The security men didn’t care who she said she was.

Bettmann/Getty Images

Goldwater delegates were paired off in a buddy system, whereby they were constantly in touch with somebody from the campaign to make sure that they stayed on the team. If someone from the Scranton or Rockefeller operation tried to get them to cast their ballot for Scranton, the Goldwater forces would get in touch, have a conversation, and make sure they were still thinking the right way. They may also have been prohibited from swimming a half-hour after eating.

Delegates were instructed to look out for the attentions of young ladies who might be trying to sway them or put them in a compromising position that would make them susceptible to blackmail. Delegates were monitored everywhere they went, to and from their hotels. Everything was tracked in the headquarters. “It was like the combat information center on a warship,” writes William Middendorf, an operative on the campaign who would later become secretary of the Navy, “complete with edge-lighted plastic panels upon which we scribbled data with grease pencils.”xxii

The Goldwater team also set up its own independent communications system. They not only ran telephone wires from the headquarters to each of the 36 hotels where Goldwater delegates were staying, but also had two kinds of walkie-talkie systems to keep communications flowing, all with a jamproof antenna.xxiii If any delegate got wobbly or the state total fell below what was expected, Goldwater troops could pounce. The security detail was armed with tape recorders and Polaroid cameras, as well as the rules of delegate selection in all states, ready to file suits if there was any funny business. The Goldwater supporters in the rafters may have been kooks, but the fellows in narrow ties in the windowless trailers outside the hall, were highly competent kooks.

The tension between Goldwater supporters and moderates led to confrontation at unexpected times. “You’re nigger lovers—communists!” someone yelled at James Brophy and family when they left the Georgia delegation for Goldwater and switched to support Scranton.xxiv

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the winner of the New Hampshire primary that year, was accosted by a man who said, “I voted for you in 1960, but never again, you’re terrible.” Lodge was seen as the quarterback behind the Taft defeat in 1952 and chief archetype of moderate Republicanism. Lodge replied, “You’re terrible, too.”

Ambassador Lodge had come back on a mission to save his party after a young captain in Vietnam asked him if he was going to return to “help Scranton.” In his suite visiting with Newsweek editor Osborn Elliott, Lodge asked, “What in God’s name has happened to the Republican Party? I hardly know any of these people.”

Whoever those new people were, they were attracting converts faster than Scranton was. Gov. Jim Rhodes of Ohio, who had been one of the coordinators of the Stop Goldwater efforts at the Cleveland governors’ conference, threw his support to Goldwater. He told Scranton that he thought the backlash in Ohio cities against race riots might be replicated in other places. It was beginning to appear as if Goldwater had a bigger movement behind him than any of his detractors had supposed. He predicted that he would surprise everyone just as Truman had done against Dewey in 1948.xxv

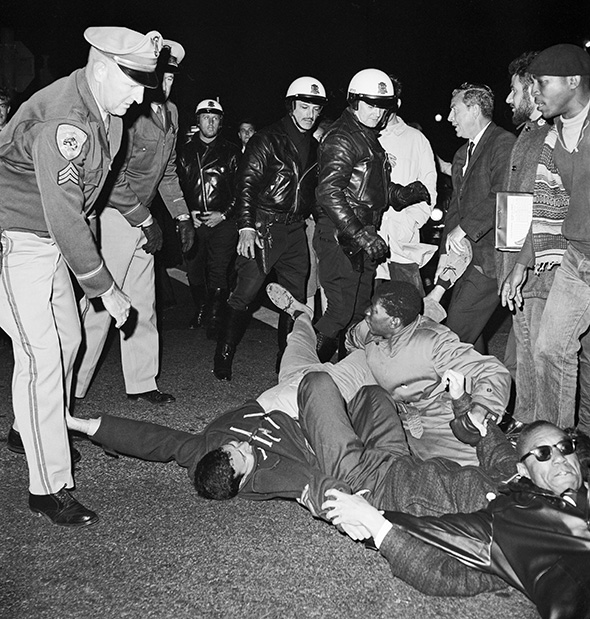

Outside the convention hall, the anti-Goldwater demonstrations continued. Protesters from the Congress of Racial Equality were trying to block the delegates from getting into the Cow Palace. “Barry Goldwater must go,” they chanted. There was a forest of creative expression: “Defoliate Goldwater,” “Vote for Goldwater—Courage, Integrity, Bigotry.”xxvi

The 40,000-person demonstration in San Francisco was the largest protest since the March on Washington. Signs read, “Goldwater for Fuhrer, Freedom Is Dead, Hitler Was Sincere, Too.” “Goldwater in ’64: Bread and water in ’65; hot water in ’66,” “Vote for Barry, stamp out peace,” “I’d rather have scurvy than Barry–Barry.”xxvii At another Goldwater rally a sign read, “Barry go home,” with a swastika in the O of home.

Even Lyndon Johnson’s strategists worried about the backlash. They called the marches and riots “Goldwater rallies,” because they feared the violence would push white voters to Goldwater.

Bettmann/Getty Images

Having failed to win over delegates, Scranton’s last, desperate gambit was to draw Goldwater out, in the hopes the Arizonan’s famous loose tongue would embarrass him and send scared delegates running to Scranton. “Will the convention choose the candidate overwhelmingly favored by the Republican voters, or will it choose you?” Scranton asked Goldwater in a letter. (He was relying on his own polls to make that assertion about the Republican voters favoring Scranton over Goldwater.) “With open contempt for the dignity, integrity, and common sense of the convention, your managers say in effect the delegates are little more than a flock of chickens whose necks will be wrung at will.” The letter continued, excoriating Goldwater for his casual approach to the use of nuclear weapons and charging that he had allowed himself to be used by radical extremists. Finally it threw down a challenge to debate before the voting: “You must decide whether the Goldwater philosophy can stand public examination—before the convention and before the nation.”

Goldwater erupted. He and Scranton had been friends. They’d served in the same Air National Guard unit together while in Washington. Their wives were friends (and stories during the convention attested to the women promising to maintain their friendship). Scranton had said before running that he had no intention of attacking Goldwater. But this was a full-throated assault. Even Rockefeller hadn’t gone this far.

Goldwater responded with a terse statement: “Governor Scranton’s letter has been read here with amazement. It has been returned to him.” The Goldwater campaign sent out thousands of copies of the two letters to delegates. Scranton had written the letter— or more accurately, an overheated aide had written the letter—in the thrall of their own spin. The Scranton camp assumed the delegates were looking for a way to get away from Goldwater. Nope, they loved Goldwater. When those delegates saw how they had been characterized in the letter and how Goldwater, their pick, had been described, they became even more supportive of him. To other delegates, Scranton just looked reckless. There were reports that the letter had caused Scranton to even lose support from some of his own people.

Other moves, like an effort to get the platform committee to attest to the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act, also failed. The final attempt to change the dynamic would involve embarrassing Goldwater in front of the television cameras, to either shake loose delegates or at least gain leverage for changes in the party platform.

The television networks had put a lot of effort into covering the 1964 convention. There were 5,423 credentials issued for the press, of which 3,963 badges were issued to representatives of radio and television stations.xxviii They built power substations and constructed sky boxes high above the seats so that wise commentators could survey the groupings of delegates like armies on the battlefield. ABC pulled in a general for the task. Eisenhower was hired as an official commentator for the network.

Rockefeller’s speech on extremism was intended to take full advantage of the television spotlight. Its official purpose was to plead for an amendment to the platform, proposed by Pennsylvania Sen. Hugh Scott, denouncing “extremist” groups. But the Goldwater forces knew it was a veiled attack on their candidate. The third-term senator had the support of the virulent anticommunist John Birch Society, which he refused to distance himself from, even though its leader had accused Eisenhower of treason and being a communist agent.

Melvin Laird, a congressman from Wisconsin and future secretary of defense who was running the show for Goldwater, thwarted Rockefeller by asking that the platform be read into the record before the governor spoke. The platform was 8,500 words. It took 90 minutes. Rockefeller was pushed out of primetime.

Journalist Murray Kempton’s description of the response to Rockefeller captures the party tension so well, Richard Norton Smith made it the epigraph of his Rockefeller biography: “There came down upon Rockefeller from those galleries a howl of hatred which was not of an opinion but of a human being who embodied everything these people had hated for 20 years ... He just stood there and began his prose in the armor of a magnificent contempt. Who cares what he said; it was what he was that night.”xxix

When the convention finally voted, Goldwater swamped Scranton. He got 883 delegates and Scranton just 214. As a show of unity, Scranton walked to the podium to urge a unanimous vote for Goldwater. He was greeted by cheers of “We want Barry.”xxx

For Barry Goldwater and conservatives, the victory was a turning point in the history of the cause. They had won, but also the establishment had lost. Richard Nixon shared the lesson he’d taken away from the shift in party politics in a conversation with aide Pat Buchanan, saying, “Buchanan, if you ever hear of a group getting together to stop X, be sure to put your money on X.” Nixon’s argument was that anybody who has enough power from the people to require a movement to stop them has the power of the people, and that’s all you need in politics.

Bettmann/Getty Images

But Barry Goldwater didn’t have all the people. He went on to lose to Lyndon Johnson in one of the most lopsided defeats in history. In a campaign ad, Johnson returned to the Cow Palace convention and the ideological splits in the Republican Party. In the spot, a jittery Republican voter, dressed in a dark suit with standard-issue glasses, engages in a therapy session with the viewing audience about his fears about Goldwater. He’s a little undone and one gets the impression that he (or the actor playing him) will conclude his remarks and rush to the first bar he finds on Broadway for a double:

I’ve always been a Republican. My father is, his father was. The whole family is a Republican family. I voted for Dwight Eisenhower, the first time I ever voted. Goldwater, now it seems to me we’re up against … a very difficult kind of a man. This man scares me … I wish I was as sure that Goldwater’s against war, as I am that he’s against some of these other things. I tell you, those people who got control of that convention, who are they? I mean, when the head of the Ku Klux Klan, when all these weird groups come out in favor of the candidate of my party, either they’re not Republicans or I’m not. I’ve thought about just not voting in this election, just staying home. But you can’t do that because that’s … that’s saying you … you don’t care who wins. And … and I do care. I think my party made a bad mistake in San Francisco. But I’m gonna have to vote against that mistake on the third of November.”

Vote for President Johnson on Nov. 3. The stakes are too high for you to stay home.

Even in defeat, the movement behind Goldwater would define the Republican Party for the second half of the 20th century and afterward. The party’s center moved west geographically—and right ideologically. Though Republican nominees would never be crowned again at the Cow Palace, the next pair of two-term Republican presidents, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, would both come from California. In 1956, the party had emerged from the Cow Palace unified behind a moderate candidate. In 1964, it emerged a party in turmoil, having selected an unelectable nominee. But the fractious, more conservative party of ’64 was the future of the GOP.

---

iii. Theodore H. White, The Making of the President 1964, Kindle ed. (New York: HarperCollins, 2010), p. 211.

v. David Reinhard, The Republican Right Since 1945 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1983), p. 155.

viii. To Defeat a Maverick: The Goldwater Candidacy Revisited, Presidential Studies Quarterly, p. 667

xiv. “Scranton’s Decision to Run: The Events Leading Up to His Change of Mind,” New York Times, June 21, 1964.

xxi. J. William Middendorf II, A Glorious Disaster: Barry Goldwater’s Presidential Campaign and the Origins of the Conservative Movement, Kindle ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2008), p. 109.

xxviii. The Magic Lantern, p. 37. In the Magic Lantern: Television Coverage of the 1964 National Conventions Author(s): Herbert Waltzer Source: The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Spring, 1966), pp. 33-53.