When Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., learned that he had won the New Hampshire primary without campaigning or being on the ballot, he was nearly 9,000 miles from Concord, New Hampshire, flying over southeast Asia. He heard the news on Army radio.

1964 was shaping up to be a big year for the American commitment to South Vietnam, and Lodge, as U.S. ambassador, was returning from a barnstorming tour near the Vietnamese border. He descended to the tarmac in Saigon in a worn straw hat, his sleeves rolled up. He was, according to the New York Times, “obviously delighted.” He grinned and waved to the gathered reporters.

“I am precluded by Foreign Service regulations from talking politics,” he told them.

“Are you happy?” asked one.

“I am happy by nature,” he replied.

It was unusual that a man like Lodge—a former senator, ambassador to the United Nations, and vice presidential candidate—would accept a post in the relative backwater of South Vietnam. But when President Kennedy, after defeating the Nixon-Lodge ticket in 1960, asked him to go, Lodge assented. He felt, as reported in Anne Blair’s history Lodge in Vietnam, “that he had one more tour of public duty in his system.”

By résumé and pedigree, this descendant of two historic Massachusetts families epitomized an era in U.S. foreign policy that was reaching its end in Vietnam. In 1944, he had resigned his Senate seat to fight in Europe, where he singlehandedly captured a German rifle patrol. He “spotted the Germans a long way off,” one soldier told Time. “When we got close to them, Colonel Lodge pulled out a pistol, leaped out of the jeep, and the prisoners threw their hands in the air.” He served in the cabinet of a Republican president, Eisenhower, who prized covert operations; he was a highly visible spokesman for U.S. foreign policy as the CIA reinstated the Shah in Iran and overthrew Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala. He was a mid-century American diplomat, to whom foreign governments were game pieces in Cold War strategy, and deposing them was as natural as moving a carrier group. By January 1964, five months after he arrived, Lodge had presided over two U.S.-backed coups in South Vietnam.

But the story of how Henry Cabot Lodge won the first presidential primary of 1964 is not a story about Vietnam. It is hardly even a story about Henry Cabot Lodge.

* * *

In the wake of the Kennedy assassination in November—and a respectful hiatus in politicking that lasted until January—the Republican race to oppose President Johnson was heating up, and the narrative was clear. It was an ideological clash between two front-runners: Gov. Nelson Rockefeller of New York, whose centrist views reflected the GOP of past generations, and the stridently conservative Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona, whose supporters in the west and southeast were later the nucleus of the Reagan Revolution.

The first contest, in March, would be New Hampshire. The Granite State, far closer to Rockefeller’s political base than to Goldwater’s, was of particular importance to the governor. “By late January,” writes Robert Johnson in his 2009 history All the Way with LBJ, “Rockefeller started calling the primary a significant test.”

In reality, however, establishment interests in the northeast were fond of neither candidate. Rockefeller, though a rich east-coast insider himself, had never been a darling of his fellows, and a divorce and new marriage hadn’t helped. Goldwater meanwhile was simply too conservative, with the bothersome and irremediable habit of saying what he thought. At one point, he suggested sawing off the east coast and letting it float out to sea, a quote that eventually featured in an LBJ campaign ad.

And in the early 1960s, the establishment was still the Establishment. In the halls of commerce and government, a search for alternatives commenced. In The Making of the President 1964, journalist Theodore White chronicled the boomlets that accompanied each possibility: Gov. Romney of Michigan? Gov. Scranton of Pennsylvania? President Eisenhower’s brother Milton? None materialized. Dwight Eisenhower himself called Henry Cabot Lodge and asked if he would return from Vietnam to run for president. Lodge declined. As New Hampshire approached, it was looking like the Rockefeller–Goldwater bout everyone expected.

That was when four friends—“looking for something exciting to do,” as Robert Johnson puts it—opened a Lodge for President office in Boston. They had grown close in 1962 working on the Senate campaign of Lodge’s son George, who lost John Kennedy’s open seat to John’s brother Ted.

Two years later, when the four-person staff of Lodge for President could prove no affiliation with their candidate, the Massachusetts government shut them down. They quickly reopened across the border in Concord. Theodore White, as if advertising for Warner Brothers, called their exploits a “madcap adventure” and “the most lighthearted enterprise of the entire year 1964.”

Their ringleader was the businessman Paul Grindle, whom White described as “a man with a delicate, satiric touch of mischief.” The New York Times, after taking a more literal approach—“a man of medium height and weight, with the promise of an expanding waistline”—also found poetry, calling him “a man in search of new worlds to conquer.” Born in 1920 in Blue Hill, Maine (where his ancestors made landfall in 1760), Grindle was raised outside of Boston. His father Maynard spent 50 years as farm manager for Richard Saltonstall, whose brother Leverett Saltonstall replaced Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., in the Senate when Lodge went to war in 1944. Their great-grandfather, the first Leverett Saltonstall, had served in Congress a century before. This was the environment in which Paul Grindle grew up, and he saw Massachusetts money and politics from an early age.

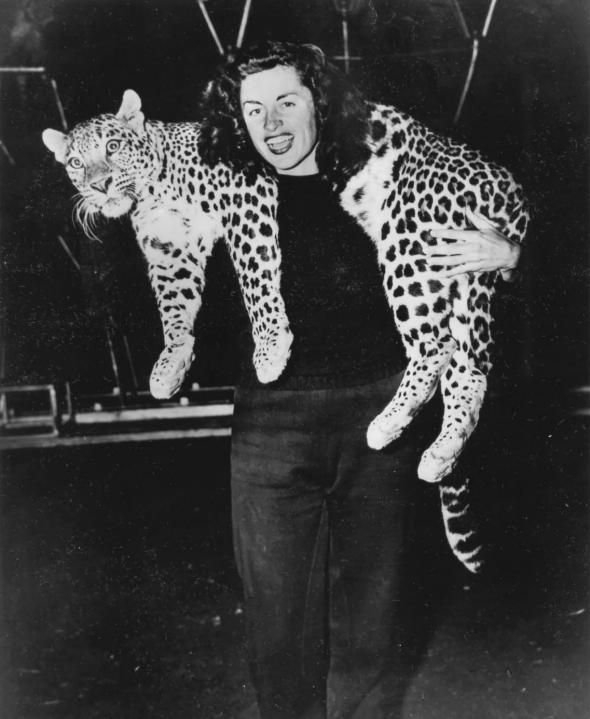

Grindle enrolled at Harvard and, in a cliché of great biographies, left after a year. After a few months in the Army, he took work as a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, where “his brashness”—according to cross-town big sibling the Times—“won the admiration but not always the approval of his editors.” Assigned to cover Barnum & Bailey, Grindle fell in love with the feather-covered, leopard-carrying horseback rider who appeared on the circus brochure, a woman named Patricia Walsh. (The Arizonian daughter of a Canadian-Irish doctor and his Apache wife, Walsh graduated from the University of Arizona in 1942—unlike Goldwater, who left after a year.) Grindle followed Walsh from city to city. Eventually he succeeded. He sent home a telegram: “I married Leopard Woman.”

Lucretia Grindle

Grindle soon left journalism and built a restless, peripatetic résumé. Most of his jobs were in sales and public relations, but it was running a furniture factory that he had his first brush with strange and forgotten history in American politics. In 1949, a D.C. facilitator named James Hunt approached Grindle and offered to bribe military acquisitions officers on his behalf. For his trouble, Hunt would take a 5 percent cut. Instead, Grindle handed the story to his friends at the Herald Tribune, prompting a congressional investigation and making “five-percenter” a household term, at least for a time.

In the late 1950s, again restless, Grindle went to the library to find the future, and after a couple days he had his answer: The future was in science. He left the library, formed the Ealing Corporation, began importing instructional laboratory equipment, and for a while—using early computers to organize catalog mailings—he had found his calling.

At one point, Grindle was bringing scientific equipment out of the Soviet Union on Scandinavian Airlines—on a fly-now, pay-later program that he had suggested—and selling it to the Indian government for nuts, which he shipped to the British Merchant Navy. The pounds he earned went to a Scottish factory to sew Shetland sweaters he then imported into the United States and sold to Brooks Brothers—the going rate for sweaters being more generous than the currency exchange. By 1964, according to the New York Times, the Ealing Corporation was doing $2 million in business each year. It’s possible that everyone sits late at night and cooks up wild, brilliant schemes; far rarer was Paul Grindle, who woke up the next morning and made them real.

Joining him in New Hampshire were three others from the ’62 campaign: 23-year-old Sally Saltonstall, the senator’s niece; a schoolmate of hers, Caroline Williams; and Grindle’s best friend, David Goldberg, a Boston lawyer. “That first campaign for George Lodge,” said Goldberg last year, 83 years old, sharp-eyed behind wire-rimmed glasses, “was very imaginative and well-run, really a lot of fun, although ultimately a failure. We missed that high, and we were looking for an encore.”

They found Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. Their candidate gave no speeches, offered no agenda, wasn’t on the ballot, and worked at the pleasure of President Lyndon Johnson—his opponent in a potential general election. Grindle and company had no platform to run on, which suited them fine; they had joined the race, according to Niall Palmer’s book The New Hampshire Primary and the American Electoral Process, “more for the excitement and challenge than from any deep-seated political principles.”

They decided to sell their product the same way Grindle sold microscopes: direct mail. They acquired a list of Republican voters and delivered their message to 96,000 mailboxes. Show your support for Henry Cabot Lodge, the postcard suggested, and write to him in Vietnam! Thank a patriot for his service—Ambassador Lodge, U.S. Embassy Saigon (c/o Lodge for President, Concord, New Hampshire). In the weeks that followed, return mail flooded the office. “We were surprised, frankly,” said Goldberg. More than 8,600 letters later, Henry Cabot Lodge had a political base in New Hampshire.

Their second mailing targeted these respondents and simply took their votes for granted. “Pick Up Two More Votes!” it read. People love to be part of something, and suddenly they were. From bucking up a great American in a difficult post abroad, they had become “Lodge supporters,” and now they were campaign workers, asked to deliver their friends. And they did. “Whatever happens,” commented Grindle, “this proves politics can be fun.” While Goldwater and Rockefeller crisscrossed the state, Grindle hunted up footage of Eisenhower endorsing Lodge and, for $750, ran it as a TV commercial. (It was an endorsement for vice president in 1960, but the ad didn’t belabor the point.) A third mailing gave election-day instructions and showed a sample ballot, marked in red to write in Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr.

On March 7, three days before the primary, Barry Goldwater left New Hampshire. “I have it made,” he said. (He did predict a surprising showing for Lodge, who would, he said, “get more votes than Rockefeller.”)

On March 10, wrote Theodore White, “New Hampshire enjoyed an old-fashioned New England blizzard: up to fourteen inches of snow from the Canadian to the Massachusetts border.” But the election went on, and less than an hour after polls closed, Walter Cronkite could announce CBS’s projection: Lodge (write-in) 33,000; Goldwater 20,700; Rockefeller 19,500; Nixon (write-in) 15,600.

Goldwater gave the epitaph. “I goofed up somewhere,” he said.

* * *

To look back 100 years to Woodrow Wilson’s re-election is to delve into history—the history of books and letters and surviving photographs. To look back 20 years to Bill Clinton’s re-election is, for most adult Americans, hardly history at all. But 1964 lies in between. It was one and is becoming the other. It’s the history of parents and grandparents. Those who didn’t live it can, if we want, still learn what 1964 felt like.

“Paul Grindle was a near genius,” said George Lodge a half-century later. “He looked around and asked himself, where do you get the best scientific educational equipment? And he discovered it was the Soviet Union. He had no money.” Lodge laughs. “He got himself to Moscow and started to import it, and it was a great success. Joe McCarthy somehow heard about this and called him up before his committee to chastise him.

“But he branched out into export-import—mainly import—and he had an incredible set of deals going. He was one of these guys who was sometimes very rich—he bought himself a castle in England, and one thing and another—and sometimes absolutely broke.”

Lodge mentions his father’s memoirs, As It Was and The Storm Has Many Eyes, which give light treatment to the primary. “The four of them, Paul and David and Caroline and Sally, had been very close to me in my campaign for the Senate in ’62,” he says. “In November or December of ’63, they came and had lunch with me. They were bored in winter, and they missed the campaign we had together. They were looking around for something exciting to do. And so Paul or David said, ‘Why don’t we see if we can run the old man?’ ”

“I had my doubts about how it was going to work, but I said, well, that sounds exciting. And really it was just the four of them, the two ladies and Grindle and Goldberg who masterminded the thing. It was quite funny because the television networks had these huge cables twisting into the headquarters of Goldwater and Rockefeller, and all of a sudden they had to have some attachment to the Lodge headquarters, which they didn’t have. And the Rockefeller people were very angry because they felt all his candidacy was doing was drawing support away from Rockefeller. But they forged ahead. They were very good friends. They loved working together.

“And lo and behold, they won.”

* * *

Lucretia Grindle

Paul Grindle died in 2008, moving 1964 incrementally into history. Seventeen years after losing his wife Patricia to cancer, he spent his final months following Obama-Clinton primary returns.

The years since New Hampshire had been lively ones. In 1966, Grindle managed the campaign of Edward Brooke, the 20th century’s first black senator. Finding his favorite hobby becoming a day job, however, Grindle left politics. He and Patricia raised four children, Lucretia and Amanda and Paul and Douglas, and two goats, Shish and Kebob. For years, he paid for vacations for two dozen family and friends in affordable locations: Grenada after the invasion, Sarajevo during the war. “The one great regret of his life,” wrote his daughter Lucretia, “was that he did not march in Selma.”

What was it like to have Paul Grindle for a friend?

“He was just marvelous,” said Lodge. “So inventive and good fun, you know. Very good fun. He was hilariously funny and cool as a cucumber. Nothing riled him. Nothing upset him. He was ready for any surprise.”

* * *

On March 16, 1964, a few days after joining Henry Cabot Lodge on his barnstorming tour of South Vietnam, Robert McNamara recommended to President Johnson that the United States “furnish assistance and support to South Vietnam for as long as it takes to bring the insurgency under control.” The next day, one week after New Hampshire, national security adviser McGeorge Bundy—on behalf of the president—enacted McNamara’s recommendations in National Security Action Memorandum No. 288, committing the United States to escalation in Vietnam.

In All the Way With LBJ, Robert Johnson ties these decisions to the early success of Lodge’s campaign. Even if Lodge was no threat to win the nomination, the White House worried that he might resign his ambassadorship and disparage the limited support he had received in Vietnam—a boon to any Republican nominee. Maybe so. Lodge did, in fact, resign to campaign, but after losing Oregon—the one ballot on which he appeared—he gave his delegates to Rockefeller, who never recovered against Goldwater, who lost in historic fashion to LBJ, who in 1965 asked Lodge to return to Saigon. Lodge accepted, serving until 1967.

In First in the Nation, Charles Brereton recounts a later meeting between Nelson Rockefeller and Paul Grindle. Laughing, the governor asked Grindle what it would have cost to get him “the hell out of New Hampshire.” A few thousand dollars, Grindle replied.

“Are you serious?” asked Rockefeller.

“I’ve never been bribed to do anything in my life,” said Grindle. “I’ve always wanted to be bribed. I always expected you to do it.”

One imagines the delicate, satiric touch of mischief, and wonders, a half-century later, how he might tell the story.