All at Sea

The view—crashing waves, a sandy beach—is spectacular. It is unexpected, because I knew nothing about and expected nothing of the port of Salalah, in the Gulf state of Oman, beyond its name. I didn't know how to pronounce that, either, until the captain told us about a girl in the office—the word office, laced with mild scorn, means ignorant shore people in this context—who pronounced Salalah like "Ooh-la-la!" (The stress, at least in English, is on the first * "la.")

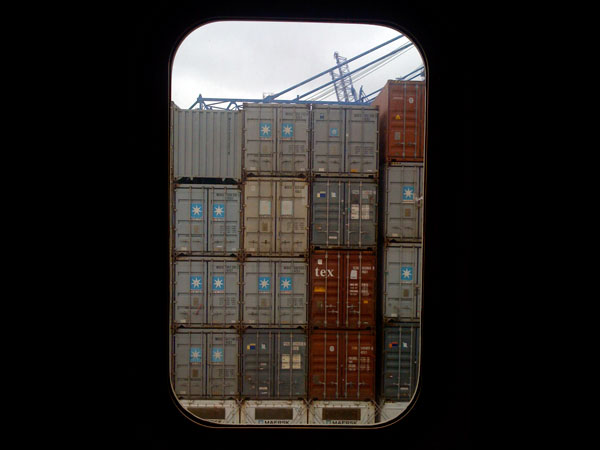

The view is from the terrace of the Oasis Club, a sizable bar-restaurant on the cliffs above the port. I go there twice in 24 hours, with whoever can grab time to come with me. The crew will never have more than a few free hours, enough time for a quick Skype call home; perhaps a chance to eat nonship food. The days of languorous shore leave are long gone. Overnight stays are unheard of and sailor towns a distant memory.

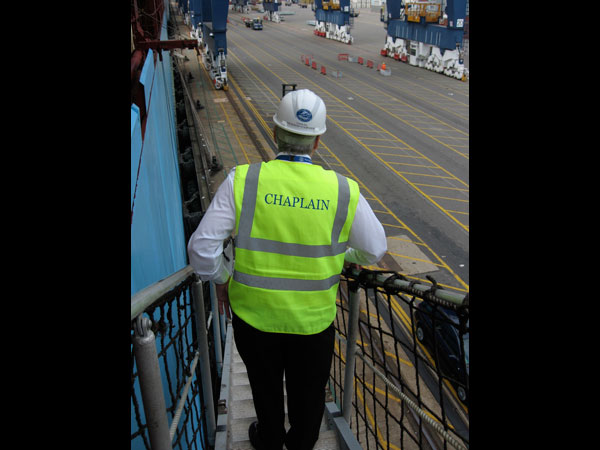

In better ports, seafarers head for a seamen's mission. There are a few hundred missions worldwide, a network run by various church groups such as Stella Maris (Catholic), the Mission to Seafarers (Anglican), and the Sailors' Society (ecumenical). The Mission to Seafarers began in Bristol, England, in 1835, when the Rev. Henry Ashley, on his way to a new parish posting, noticed the ships moored in the channel and wondered who was ministering to their crews. When it turned out to be nobody, he canceled his parish assignment and spent the next 20 years rowing out to ships, often in appalling weather—so bad he once smashed his legs and limped forever after—and being pelted with pork balls by sailors more interested in grog than God.

The Mission to Seafarers now runs 230 centers worldwide, and they are a godsend, because most are in or near ports, and seafarers lack the time or money to go farther. The missions usually provide Internet access, a bar, and souvenirs for time-strapped sailors. The popular seafarers' center at Felixstowe, Britain's largest port, carries union jack and London-themed souvenirs for sailors who can't spare five hours to get to the real capital, a two-hour train journey away. It also sells chocolate: Italians and Croatians love Cadbury; Indians prefer Quality Street.

When there is no mission, entrepreneurs sometimes step in. At Rotterdam, where the seafarers' center is 25 miles and a $140 taxi fare away, transport is provided to a nearby duty-free store. At first, I thought the shop was called Bootleg, which was satisfyingly nautical, but in fact it is Botlek, after an area of this huge port. Other wharves are named after rivers: You can be berthed at the Yangtze, Mississippi, or Amazon. Transport to Botlek is free if customers spend $140, but given the prices—twice that of supermarkets, making the duty that is free irrelevant—that shouldn't be hard.

Seafarers are used to being exploited. At sea, the captain moans at chandlers who supply ships with green bananas that will never ripen; at fruit that goes moldy obscenely fast; at sub-standard meat. He swears that he used to see meat stamped with "For Merchant Navy only." Afloat and ashore, seafarers, with constricted time, little local knowledge, and ready cash, are easy marks. A volunteer at the Liverpool mission tells me of a taxi driver who claimed that both tunnels under the River Mersey were closed (a legal impossibility) and charged Filipino seafarers $200 for a 50-mile detour on a four-mile trip. And don't get him started on what they were charged for Manchester United tickets.

At Salalah, the crew head for the Oasis Club, a private establishment that is a de facto mission, because it provides free transportation and sells steaks the size of plates. The place is packed when I visit, because a U.S. naval frigate is in port, and its inhabitants are making full use of their R&R with the help of the bar. On the terrace with the view, I meet a refreshed Navy man. He works in the frigate's accounting office, doing the books. He is merry enough to assure me that for the next day's Fourth of July celebrations, "We don't have fireworks, so we're going to set off a missile," but sober enough not to answer when I ask him where the frigate has been. I guess that it is on anti-piracy patrols, and I thank the bemused bookkeeper with some force, having just spent several days veering between anxiety and fear as we traveled through pirate-infested areas where the sight of low, gray frigates patrolling the horizon was always a welcome one.

The bookkeeper seems to be drinking off months of stress, and so would my crew if Maersk hadn't imposed a no-alcohol policy two years ago. Maersk seafarers can't drink on or off ship. They're not even supposed to drink in airports, in case they miss their flight to or from their ships. The alcohol ban is not popular. I don't agree with it, either, though I'm not a great drinker and welcome five weeks of sobriety. But after another dinner spent talking about the same things (soccer they can't watch; anecdotes they have told before; company gripes they have already made), even I can see that the policy has killed the ship's social life.

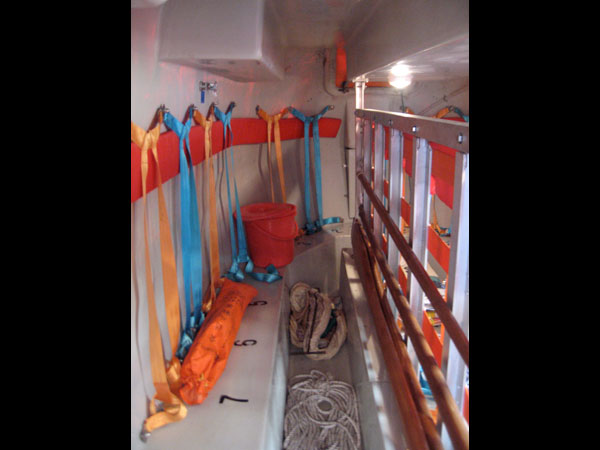

"Before," one officer tells me, "we would have a beer after work and hang out. It was only one beer, but it got everyone together." Now, everyone eats without talking and heads straight back to their cabins to sleep or watch DVDs. There are lounges on each accommodation deck, but they are rarely used, except for the odd session of caterwauling karaoke on the Filipino D Deck. Besides socializing, there is little entertainment beyond a small gym, a Wii console, and a backgammon set that I blew the dust off before starting a five-week British-Romanian contest. (Romania won.)

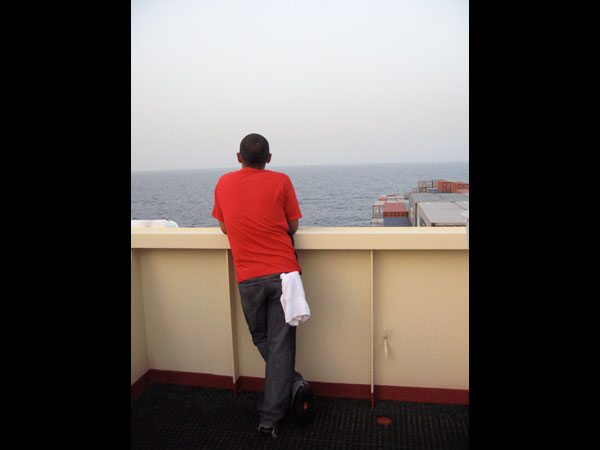

It is an isolating life. Though Kendal is a well-equipped ship, Internet access is available only by expensive satellite. Crews get one e-mail session a day. No browsing, no video chatting. Even so, the Kendal crew is better served than most: In a recent survey, 70 percent of seafarers rated Internet access as the most important onboard facility. But only 16 percent of officers have it, and only 3 percent of nonofficers. There are satellite phones, but at $16 for half an hour, it is a cost that careful Filipino savers, for example, can't justify.

In short, when you are at sea, you are at sea. The captain may bemoan the demise of the British merchant navy, but what young person from a Western European country wants to go to sea, when most of his life will be spent working, when he doesn't get to go ashore much, and when he is deprived of the social networking and facilities that all his friends have?

Seafaring can be lucrative—the elite, such as gas-tanker captains, can earn $100,000 for six months' work—but the isolation is a heavy price to pay. Suicide rates among seafarers are thought to be triple those of shore-based jobs. (It is hard to know how many drownings are deliberate.) I'm not surprised that shipping has 10,000 fewer officers than it needs worldwide or that this number is expected to triple by 2015. Many a seafarer tells me that his job is like being in prison with a salary. But a report by Britain's Maritime Charities Funding Commission in 2007 found that "the provision of leisure, recreation, religious service and communication facilities are better in UK prisons than … on many ships our respondents worked aboard."

Containerization has brought us technology, speed, and efficiency. Yet Samuel Johnson's views of sea-life in 1776 still apply. Being at sea, Johnson wrote, is nothing like being in prison. "There is, in a gaol, better air, better company, better conveniency of every kind."

Correction, Dec. 1, 2010: The author originally misstated the syllable upon which the stress is placed in Salalah. (Return to the corrected sentence.)

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.