All at Sea

They said come sooner, the vessel schedule has changed. Maersk Kendal, on which I would spend the next five weeks, had been due to sail at 11 p.m. The day before, the departure time changed to 6 p.m., and I had to dash to Felixstowe, England, from where Kendal would sail for Laem Chabang, Thailand, on its regular two-month loop. The publicist from Maersk was apologetic, but sudden changes are normal in modern shipping, where schedules and profit margins are tight. It can cost $100,000 a day to run a ship—the daily fuel consumption is 260 tons—so you don't want expensive port fees on top of that.

I arrived early, wanting to be helpful, and waited for hours. The ship was being inspected by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency, Britain's maritime safety watchdog, because unlike most of the world's 90,000 freighters, Maersk Kendal flies a British flag, though Maersk is Danish. Maersk is so Danish it contributes 15 percent of the country's GDP, and so big its ships use more oil than the state of Denmark. It is, in fact, the biggest shipping company in the world—the Coca-Cola and GM of freight—and when shipping transports 90 percent of everything, that is a hefty position to hold. (My other favorite fact: Maersk is a first name. It's like a global shipping company named Derek.)

For all these reasons I wanted to sail on a Maersk ship, though the company no longer accepts paying passengers. Nor will it allow crew members' family onboard anymore, because since piracy boomed a few years ago, the danger and the insurance premiums are prohibitive. I am a guest, therefore, rather than a paying passenger, and clearly an honored one if the luxury of my cabin is an indicator: I have a vast day room and office, a sizable bed and en-suite bathroom. It is better than many hotel rooms I have stayed in, and this one floats.

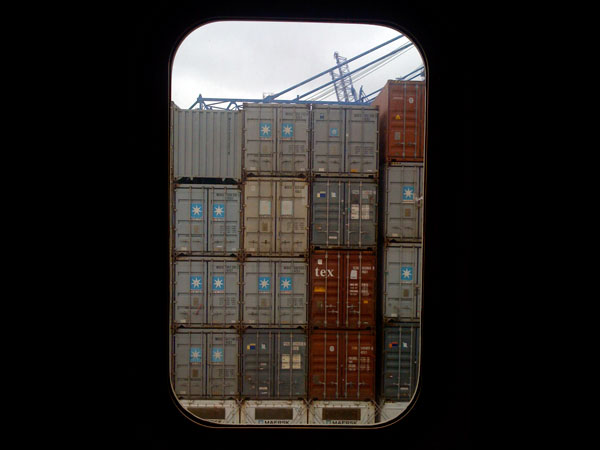

I pass the time before sailing by watching boxes. Every port between here and Singapore, where I will disembark, requires containers—"boxes" in industry language—to be laden and others to be discharged. It is a constant, relentless business. Felixstowe, the United Kingdom's largest port, stops work only for Christmas Day and for crane-toppling Force 9 gales. When fully laden, Kendal carries 7,000 containers. This makes her a midsize ship—Maersk E-class vessels have carried 15,000 boxes—though to me she is immense.

Once at sea, I take to walking the decks every morning, all four football fields of length, and the boxes are inescapable. They rise 10 stories up to the bridge; several decks down into the hold; and out over the deck passageways so that they serve as their ceilings and walls. They are also my shelter, because on the fo'c'sle—in my shore person's language, "the pointy bit"—the bridge can't see me for the wall of corrugated iron containing who knows what. It's just me, the bulbous bow, and dolphins.

I find the boxes mesmerizing, though I am the only one onboard to think so. An engineering cadet (in other words, a trainee) is typical in his opinion of them. "Boring. You can't see what's in them, and it's always the same."

The ship carries a manifest only for dangerous goods, so that the crew members know what to do when one catches on fire. (Despite traveling in containers that are only weatherproof, many chemicals transported by sea react dangerously with water. We were later to sail past Charlotte Maersk, ablaze for 10 days off Malaysia.) I wonder aloud about perfumes and children's toys; firewood and car batteries. Nearly everything I am wearing came by ship, along with my laptop, the ink in my daily newspaper, the coffee in my cup, and the food on my lunch plate. But the captain refuses to be curious. "I don't care." They are boxes to be moved from loading port to discharging port, quickly, so long as pirates don't have other plans.

The captain and I differ on boxes, but we agree on one thing: This is a lovely ship. He is immensely proud of her, and he strokes or taps some part of her every day, a formal and ritual greeting. Despite a modern trend in some maritime journalism to call ships it, he is defiant. His ship is a she. Why? She just is. She has served him well, despite being only three years old. Only 15 days into her first voyage, Kendal rescued six Thai fishermen from the South China Sea in awful weather and poor visibility. Five of their crewmates died. The captain counts the rescue as his proudest moment in four decades at sea.

His 40 sea years have paralleled a period of dizzying change in shipping. When he started out as a cadet in the British merchant navy, there were 101,400 Britons earning their living on merchant ships. Now there are one-quarter of that and dropping. When the captain was a cadet, there were hardly any boxes; now he transports nothing but. Ships are almost unrecognizable from the vessels he first lived on. They are guided by gadgetry and steered by the kind of wheel you would find on an arcade car-chase game. Soon ships will sail themselves. But some essential aspects are unchanged. The sea still kills, despite all that technology. Ships are as vital to our modern consumer society as they were to Queen Hatshepsut, the Egyptian pharaoh who sent a fleet of ships to the Land of Punt, becoming the first shipping agent in recorded history. And the men who sail those ships are still criminally disregarded by us shore people. "The merchant navy is the scum of the earth," says the captain, regularly. "Always have been, always will be."

On this ship, the scum of the earth consist of seven nationalities. The crew are all Filipino; the officers are from all over. This is not unusual in modern shipping. Since the 1920s, when some U.S. cruise ships decided to fly a Panamanian flag to avoid Prohibition regulations, ships have commonly flown the flag of countries foreign to their owners. The benefits are obvious: lower taxes, laxer labor and safety laws. "Flagging out," in the words of an Australian seafarers' union, is "like being able to register your car in Bali so you can drive it on Australian roads without having to get the brakes fixed." The biggest shipping fleets in the world belong to Panama and Liberia, whose harbor was barely functioning when I saw it five years ago. But that is immaterial when the Liberian flag registry—a brand, really—operates from Virginia. Sixty percent of ships now sail under foreign flags, plenty of which belong to countries with no coastline, places like Bolivia or Mongolia.

When there are few restrictions on labor, you pay for the cheapest. Western Europeans have now been priced out of the market. MaerskKendal is a rarity with its British flag, the "LONDON" home port painted on its bow, its two British chief officers, and its portrait of the queen in the mess room, apparently common courtesy on British ships, but a little alarming to me. Under the watchful gaze of her majesty, I eat alongside a Burmese and across from a Romanian, a Moldovan, and an Indian. Behind me there is a Chinese engineer, two Filipino electricians, and two young British cadets on their second compulsory three-month period at sea. The louder lad is from a small Scottish island and a family of seafarers; the quieter one, who gets quieter as sea days mount along with his homesickness, is a Geordie—from the northeast of England—like the captain. They are unusual, these lads, because hardly any Britons go to sea anymore.

In 2009, a British admiral accused his island compatriots of "sea blindness." This is not a new complaint: In 1910, journalist F.H. Bullen wrote that "ignorance of our greatest industry is universal. ... Our people have grown to look upon this indispensable bridging of the ocean for the supply of our daily food as something no more needing our thoughtful attention than the recurrence of the seasons or the incidence of day or night." Or as the captain might say: Merchant navy, scum of the earth.

The bringing of our daily food is now done by the world's poor. Worldwide, Filipinos make up one-quarter of all seafaring crew. Pakistanis, Indians, Indonesians, and Chinese are also common. Filipinos are most popular because, several tell me, "We are cheap and speak good English." The Chinese don't speak good English, and Indians aren't cheap. Officers, apart from the odd Western European (and Americans on U.S. ships, still ruled by the unions), come from countries with good maritime academies and turbulent economies: Ukraine, Russia, Romania. Kendal's third mate comes from the Romanian port of Costanta. He is the first of his family to go to sea, and he isn't sure why he did. Now he is too tired to think about it, what with two four-hour watches a day, and 18-hour workdays in port, now that a container ship as big as this one can be loaded and unloaded in less than 24 hours.

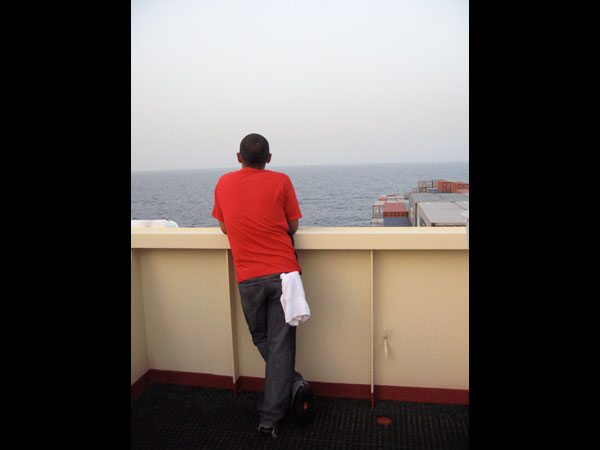

It is a relentless life and difficult. In the crew mess-room on my first day, I meet the crew. They are chatty and sociable. Introductions are made, so that I know that the bo'sun is Elvis, an AB (able seaman) is Archimedes—Archie for short—and there is a sparky (an electrician) called Dilbert. I ask them why they went to sea, and they give an "it's obvious" shrug. Money, money, and money. Another Filipino seafarer I met ashore earned more as a ship's cook than he did as a high-level government employee in Manila. These men earn less than officers, but it is still a decent wage, enough to pay for education for their families, to build a house, to buy a future. The price of this money is high. With nine-month contracts, they regularly miss births and birthdays.

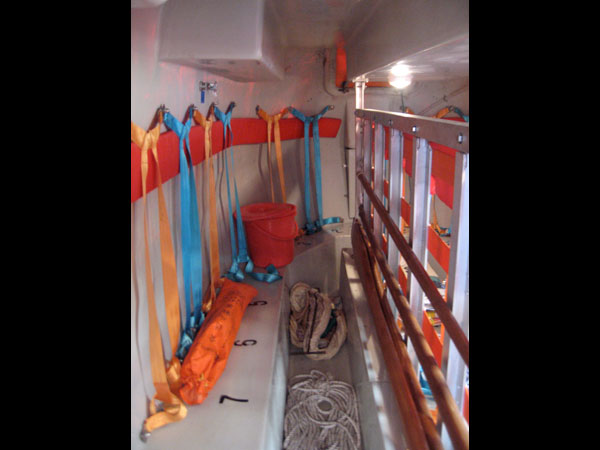

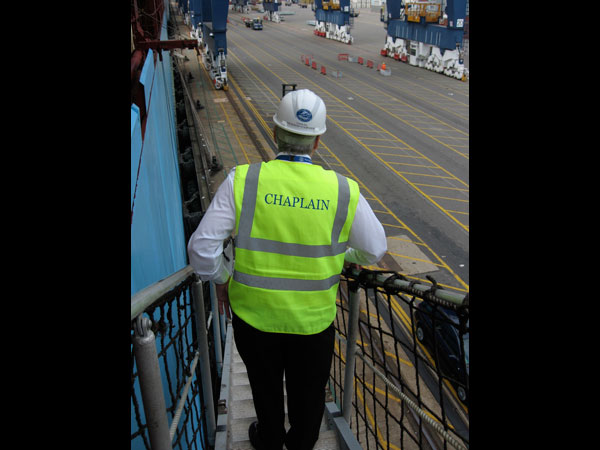

They work hard and sleep with difficulty (engines throb; in port, containers and cranes clank). If anything goes wrong—seafaring is the second-most-dangerous job in the world after fishing—they have none of the luxuries of shore life: an emergency number, a union representative, a lifeline. There is no Internet to browse and no mobile phone signals with which to call home. It is a dangerous, isolating, but priceless job, without which society would immediately and drastically suffer, and they know its cost. "The ship company," a Filipino seafarer once told me, "is not really paying me for my work. He is paying me for my longings for my children. He is paying me for my loneliness."

Launch as slide show on shipping.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.