All at Sea

This is the kind of heat that sucks the breath from bodies. We are in the Bab al Mandeb Strait, a narrow opening that marks the beginning of the Gulf of Aden. It is July, now, and almost monsoon season. Monsoon weather is bad for nausea, but good for anyone scared of pirates, because these modern sea-jackers travel in small boats that are upset by the Force 6 waves that our ship slices through with ease. There may be frigates around, but much of our protection is weather.

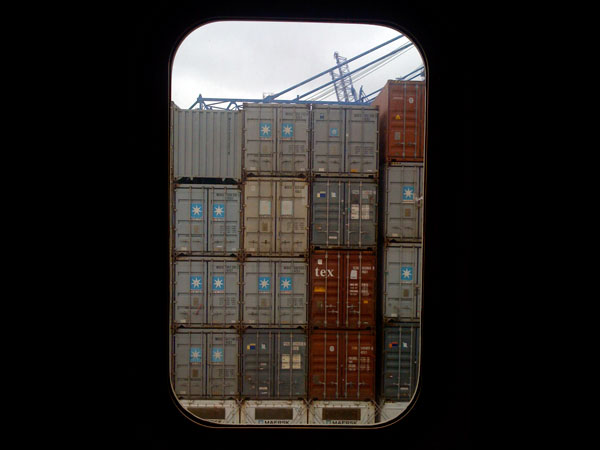

We have been on pirate watch for one day now. The ship has changed: The portholes in the doors on each of the six decks in the accommodation house have been blocked with circular pieces of cardboard, cut—I see on closer inspection—from chocolate boxes and cigarette cartons from the bond store. All windows must be covered by sundown with blackout blinds that are fastened into place with snaps, the better to defeat chinks.

Pirate watch requires two extra men on the bridge for lookout duty. This job falls to the ABs, the able seamen, and cadets. It is boring and hot, particularly as they wear heavy overalls. I'm not sure how useful the lookouts are, given the ship-sized blind spot caused by the containers, but I don't mind, because I am nervous.

One of the first things the captain asked me was: "Why do you want to go through pirate zones when you don't have to? Are you mad?" It is only now that I think the answer to the latter is yes. During the first night of pirate watch, I stay awake until 2 a.m., as if that will help. It is foolish. Pirates like to attack at dawn anyway. I sleep uneasily and wake to the ridiculously cheery bong-bong (think summer-camp loudspeaker) of the ship's alarm call. I jump out of bed in alarm, expecting an "Abandon Ship" or a call to the safe room where we have agreed to muster in the event of an attack. But nothing happens. It's someone phoning home again. They always press the wrong buttons on the satellite phone and make an inadvertent public address.

Later, I tell the second officer about my uneasy night. He laughs at me. He thinks we are protected by the size and speed of the ship. Even so, there was a definite near-attack during his night-watch. Four fast craft, doing about 20 knots at 2 a.m. That is either pirates or people-smugglers, and who wants to be smuggled from Yemen to Somalia? They reached the bow and stopped. The second mate shone searchlights on them. He laughs again. They saw the size of the ship and fled.

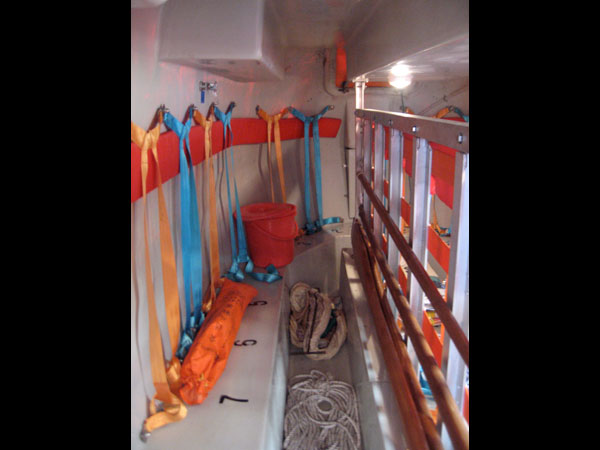

Pirates have never dared capture a ship our size because our 10-meter freeboard (the height of the ship between waterline and deck) is daunting. But there are weak spots. At the poop deck, nets are slung over openings that could become access points. Astern, there are hoses port and starboard, jetting water. From the bridge they look like a pathetic deterrent, and I assume that a damp pirate can still perform piracy, but I am told that the jets are stronger than they look. Even so, what use is a hose when they've got AK-47s?

The tension of pirate watch is hard on the crew: Some are genuinely unnerved, and being genuinely unnerved for a week in every month is not nothing. The captain received a communication from Maersk prompting him to order barbed wire. He duly did so and was told that his ship was too big. It didn't need barbed wire. It didn't need armed guards. Most of the officers disagree with this. "Pirates haven't attacked a 10-meter-high freeboard," says the captain. "But there is always a first time." Most of the officers favor armed guards, though company policy is not to use them. At dinner one evening, I remark that the International Transport Federation has organized a petition against piracy. The Moldovan nearly snorts into his soup. "So what do we do with a petition?" he says in his Bond-villain-accented English. "Send it to Somalia? 'Please stop attacking us.' The only thing to do is to send the petition with an A-bomb in the envelope."

The third mate keeps quiet. He is the least worried of all of us, because before he transferred to Kendal, he was on a smaller ship doing the run from Salalah down to Mombasa, Kenya. It was a sister ship to the now notorious Maersk Alabama, which was captured by pirates in 2009 and whose captain was taken hostage and dramatically rescued. Same size, same route. The third mate has heard that the Alabamawas a hostage-taking waiting to happen, because it was sailing 300 miles off the Somali coast, when company policy specified that it should be 600 miles from shore. "When I left that ship, I said to myself, I'm going to see the Alabama in the news."

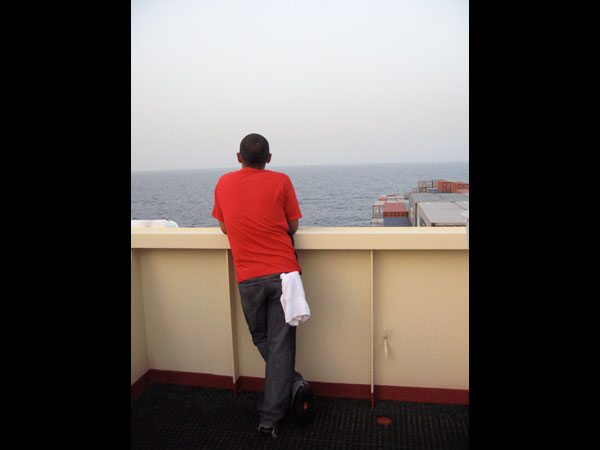

But even the phlegmatic third mate does not have the profound calm of Able Seaman Archimedes, whom I talk to one afternoon while he is on bridge-watch duty. It is the day after the near-attack, and he is scornful of the watch-officers. Scared of fishing vessels! So nervous! He would not have been scared because, he says calmly, he doesn't believe in pirates.

"What do you mean, you don't believe in pirates? Like fairies?"

"I don't believe. Suspicious craft, yes. But I won't believe until I see them."

I am not sure how to respond to this. It is such an outlandish thing to say. I tell him the figures of piracy: 544 seafarers taken hostage in the first six months of 2010, with 360 still being held. Thirteen ships hijacked, the 13th—the chemical tanker Golden Blessing—only the day before.

"Yes," he says. "I know all that. A friend was held hostage for three months. But it was good. Double pay! Overtime!" And the Greek owners paid for three months' holiday afterward, too. The captivity was fine, and the pirates were harmless. Harmless with guns? He grins again. Guns just for protection. They don't want to shoot you. They just want the ransom.

I had forgotten this when I asked the captain how pirates would reach the top stacks of containers, which are 10 stories high. He looks at me and adds it to his mental list of daft passenger questions. "They won't. They're not interested in the cargo. They only have beaches in Somalia, they can't even unload it." All they want is the ship. They want slow-going ships with expensive cargoes, so mostly they like oil tankers, which are both slow and low in the water. But they are adaptable, says the captain, and they are not stupid. It is only a matter of time before they upgrade.

The military presence of NATO frigates is comforting, but only up to a point, since a successful pirate attack can be achieved in 15 minutes. If a ship has a sensible reaction plan; if someone can cut the engines and someone radio for help; then drifting might give the navy time to arrive. There are usually 30 or so frigates patrolling at any one time, but the distances involved are dizzying. A NATO commander recently compared his job to "patrolling Western Europe with a couple of police cars."

But even if the pirates were arrested, what then? Nobody wants to try them. The Seychelles is being groomed to be the pirate court of choice, an international piracy expert tells me, but for now it's a small island courthouse, and overwhelmed. Kenya has no room or inclination, either. There have been trials in Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States, but those were show trials, and expensive ones at that. When, last year, it was revealed that the Russian navy had set 10 pirates adrift with no navigation aids in the middle of the Indian Ocean, there was little surprise in the shipping world. It's one way of dealing with them.

I don't know what is going to change things, says the captain wearily at the dinner table, after two days of pirate watch. Not some bloody petition. He and his crew will just continue to keep sailing through this danger, month in, month out, and that's that. "I told you. Merchant navy. Scum of the earth."

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.