All at Sea

The bridge is an aerie. There is a sofa, a kettle for tea and coffee, and, if I am lucky, decent cookies, not just the SkyFlakes crackers that Filipinos tell me are their only food back home in bad weather. Typhoon crackers. There is also the VHF radio to listen to. My untrained ears find most radio transmissions undecipherable, but the watch officers are used to them and can translate. They speak fluent Maritime English—this might consist of English that is broken, pidgin, Filipino, or Chinese—while I am still learning.

I spend hours up here, hanging out, and the watch officer is always hospitable, because he is bored stiff in open ocean, and he is not permitted to sit down in case he falls asleep. Sleep is banned on the bridge, and a "dead man alarm" must be switched off every 11 minutes to prove that the officer is watchful. But if he is busy, I read the charts and note the names that appear on them, because sometimes they are lyrical and lovely. Adventure Bank, Terrible Bank, Locust Patch. Hecate Patch, Herodotus Rise, Hellenic Trench.

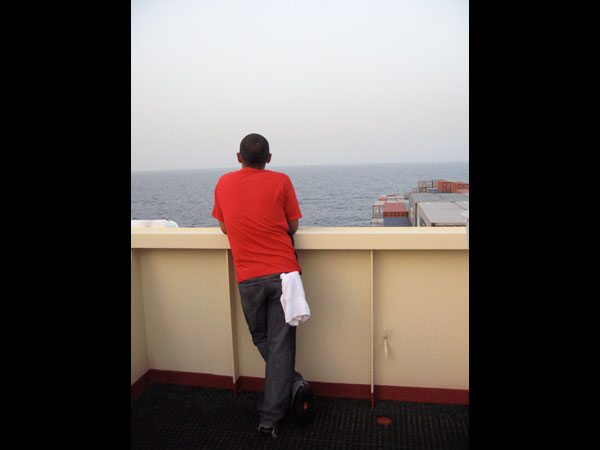

A Moldovan officer finds my interest in the charts unfathomable and asks about it. It is because of their words, I tell him. It is because I am romantic about the sea, and I like to think of men who sailed through emptiness and attempted to anchor it with names. Knob Channel, Black Deep, Tail of the Falls. Fairy Bank, King Arthur Canyon, Shamrock Knoll. Aren't they beautiful? "Words!" he grunts. "For us, it is just work."

Apart from chart-tables and coffee-making, the bridge is mostly windows—with windscreen wipers—and high-tech instruments and screens. There is radar, of course, and now ECDIS, an electronic charting device, which can transmit to the bridge the name, position, and speed of nearby ships. But there are remnants of old shipping life here, too, such as the beautiful brass sextant kept in a cupboard. The captain insists that cadets be taught to use it. If all technology breaks, there will always be the sun or the moon or stars—he calls them "heavenly bodies"—and the horizon with which to calculate position. The cadets are engineers, and oil (engine room) and water (deck officers) never mix, so they could be forgiven the lack of this deck skill. But there are senior officers who cannot use the sextant. The captain despairs at this. He despairs at a lot, despite claiming with some justification to be an optimist. "But I've been doing this job too long. Forty years is a long time."

Nonetheless, he is always happy to educate me, an ignorant shore person, when we are both on the bridge. Only in tight and busy channels such as the Singapore Straits does he excuse himself, because the radar there shows a mass of dots, and each dot is a ship that the captain must navigate around. The channel is only a mile wide in places. In the South China Sea, things are even scarier, because the seas are awash with small fishing boats that the radar doesn't see. "The cadets see all the lights and ask if it's a city," says the second officer, "but it's boats. They think if they pass in front of our bow, they will have good fishing. If we change course, so do they, so they can pass in front of us. It's a nightmare."

Usually, there is no equivalent of air traffic control at sea. Some busy areas operate "traffic separation schemes," but mostly, ships are treated like cars on roads where there are rules and codes of behavior, and successful, accident-free outcomes depend on everyone respecting them. As on roads, this doesn't always work. I ask one officer how many collisions there are with fishing vessels. "Who knows? You'd only know if you found the boat."

Last year in the English Channel, the bulk carrier Alam Pinto annihilated the Étoile des Ondes fishing vessel, killing 21-year-old fisherman Chris Wadsworth. Its failure to stop was described by the Maritime Investigation Bureau as "illegal, immoral and against all the actions of the sea." But outside the well-policed waters of the English Channel, the sea sees more actions like this than is usually acknowledged.

The captain is careful, because he believes strongly in respecting the codes of the sea. Ships that pass ahead when they should pass astern, or vice versa, bother him profoundly. But also, he needs to restore the reputation of his ship. Last year, Kendal ran aground in the Singapore Straits, when the captain's "back-to-back" (the man who is at sea while he is ashore) decided to go at 21 knots—this is fast—through a busy, narrow, and dangerous stretch of water. The chief engineer on this trip was aboard for the grounding, so I ask him whether there was a crash when the ship hit the sandbank. No, he said, just a sudden, weird halt. He wouldn't tell me which word came out of his mouth first. The repairs cost millions and took months.

Dry-dock repairs aside, the ship's route hardly varies. Felixstowe; Bremerhaven, Germany; Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Le Havre, France; Port Tangier, Morocco; Suez Canal; Salalah, Oman; Colombo, Sri Lanka; Port Klang, Malaysia; Singapore; then Laem Chabang Thailand. All those names excite me, apart from Bremerhaven (which is unfair, since it proves to have an observation tower built out of empty containers).

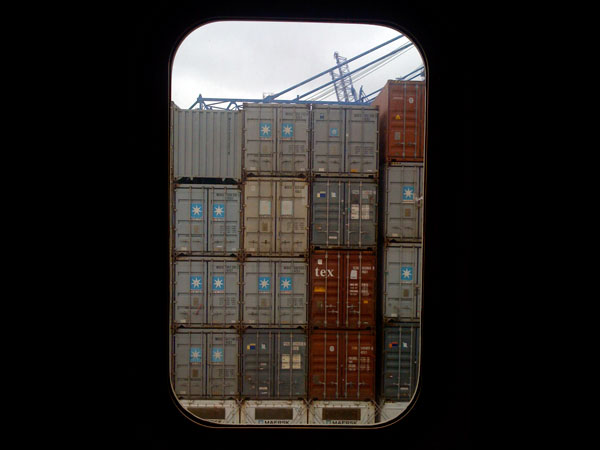

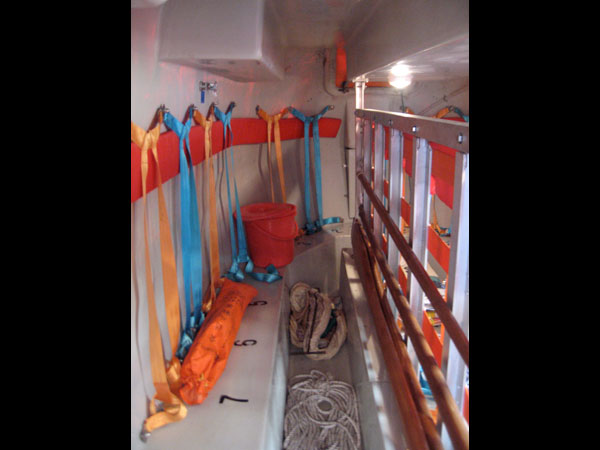

I am definitely most excited about Suez. But the crew goes through the canal once a month, and it is tedious. "It's just a ditch in the desert," they say. "You'll see." It is also a headache. Ships are obliged to take on harbor or river pilots—who provide specialized local navigation—when they approach a port, but in the canal, a Suez crew is also obligatory. The crew members are there in case the ship needs to be moored during the canal transit, but this rarely happens. Instead, the Suez crew hang out in the Suez crew cabin on A Deck for 18 hours, eating, sleeping, listening to Egyptian pop music, and trying to sell souvenirs. They all have the corpulence of the well-off in a poor country. They disembark at the canal's southern port, climbing into a small boat hitched to our side, then refusing to untether it for several miles, as if they didn't even have the energy to use their own motor.

Yet the Suez crew must be paid for their lack of services. Ships always have to pay something to someone, either officially or unofficially. Traversing the canal costs somewhere between seven and 11 cartons of cigarettes in "gifts." Without Marlboro, a dissatisfied pilot or immigration official can have the ship stopped for hours. Unplanned customs inspections, audits, immigration checks, all running up delays and costing money. The cigarettes are cheap in comparison. In some West African ports, I am told, agents and port staff turn up in the bond room with a shopping list. Chocolate, cigarettes, Coke, please.

I find Suez astonishing for the first hour. It is a ditch in a desert, but a stunning one. The sensation of being hemmed in by huge ships, moving at a stately pace through a man-made waterway, is extraordinary. Even the cadets come out on deck to take pictures and phone home. (Cell phone signals come and go with shorelines. I am particularly pleased, a day later, to be cordially welcomed by text message to Yemen.)

After Suez, we enter pirate waters. Channel 16 is suddenly listened to much more carefully. Channel 16 is the official emergency and notification channel with strict codes regulating its use. You use Channel 16 to call someone, then you both agree on another channel for further conversation. In practice, that often fails, particularly in calm waters where there isn't much to do, and where pirate-provoked tension needs release.

The Gulf of Aden, the Indian Ocean, these are the seas of name-calling. Here, it is common to hear Indian voices yelling out, "Filipino monkey!" The captain finds this unpleasantly racist, but the Filipino voices generally retaliate. "Indian, I can't see you, but I can smell you!" There is no way to tell who is calling, so bored watch officers clog the airwaves for fun. When piracy started up again around 2004, there was a period when pirates would play music over Channel 16 just before they attacked, both to unsettle seafarers and to stop ships communicating with the shore.

The second mate has spent many a night listening to weirdness. Around these parts, he tells me, you also hear ghostly voices shouting, "Mario! Mario! Mario!" It's not just him: Friends of his on other ships have made posters about the ghostly Mario-shouter, but no one knows who it is. I don't think they want to know. Strange things happen at sea, and so they should.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.