“These People Need to Know What We Have Gone Through”

The victims of crime who go to prisons to confront criminals, and why they do it.

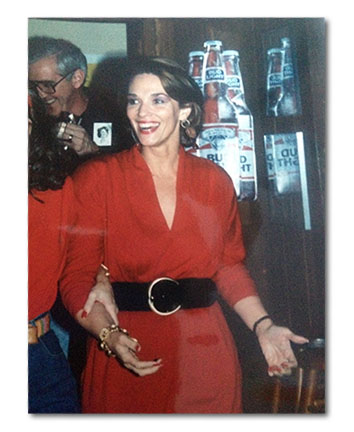

Marilyn Sage Meagher and her daughter Kelley Watts, 1990, about three years before Marilyn’s death. Photo courtesy Meagher's family.

Kelley Watts went away to college just six weeks after her mother, Marilyn Sage Meagher, was killed during a break-in at their Houston apartment. Determined not to be known as the Girl Whose Mother Was Murdered, Watts maintained the facade of a normal student: getting decent grades, partying enthusiastically, making friends who prized her for her sense of humor.

But the 1993 death of her mother left behind a powerful grief. During college and afterward, Watts suffered from depression, relationship troubles, and “lots of nightmares, lots of waking up hysterically crying.” Once, when she accepted an invitation from friends to see the Brad Pitt movie Seven, about a serial killer, Watts realized too late that the murder scenes would trigger a private horror show in her mind. She sat through the entire film, frozen in place in the darkened theater, not wanting her friends to realize she was suffering. “I didn’t sleep for three days,” she says.

Eventually, however, Watts reached an equilibrium. She found satisfaction in her work and happiness as a wife and mother, thanks to therapy, a loving family and supportive friends, and a personality that prompted one of her aunts to call her “the most resilient human I’ve ever known.”

Watts even chose a career based on her experience. Having earned a doctorate in psychology, she now counsels patients coping with grief and trauma. It comes in handy, she says, to be able to show an Iraq combat veteran that she understands paralyzing moments like the one she experienced in the movie theater, the moments when seemingly inconsequential events can bring you to your knees.

Today, Watts says she spends as little time as possible thinking about the two teenagers who killed her mother. One died of AIDS in prison. The other, who Watts sees as the ringleader, remains on Texas’ death row. “I’m done with them,” she says. “They don’t get any more from me. They’ve taken enough from my life.”

Watts wasn’t the only family member traumatized by her mother’s killing. Marilyn’s death plunged her brother, John Sage, into crippling bouts of anger and grief. He was rendered “pretty dysfunctional” for years, he says, consumed by thoughts of revenge and locked in depression. Like his niece, he eventually found relief in the form of a vocation, and one that stemmed from the loss of his sister. For the past 17 years, Sage has led a team of counselors who conduct a 14-week course for prison inmates. The program, called Bridges to Life, attempts to awake in prisoners a sense of empathy for and accountability to their victims. Once equipped with those basic skills, so the thinking goes, they will be more likely to care enough about themselves and others to live more responsibly once they’re released from prison. Some 25,000 inmates have completed the course.

Photo courtesy Mark Obbie

What sets Bridges to Life apart from other inmate educational programs is its volunteer teaching staff, made up of many crime victims or, like Sage, murder victims’ survivors. These victim-counselors deliver a message of redemption through apology and atonement, using their own painful stories to drive home the devastating effects of crime on others.

Bridges to Life thus serves as a test of whether a privately funded program that exposes criminals directly to victims’ stories of loss can accomplish what prisons for so long have failed to do: break the recidivism cycle that dooms a majority of ex-convicts to commit new crimes and return to prison. The experiences of its volunteers, meanwhile, raises another tantalizing possibility: That victims might find more solace in helping criminals than by throwing the book at them.

* * *

For a large man, John Sage moves with startling speed. In the middle of a conversation in his spartan office, the 6-foot-2, 230-pound Sage glances at his watch and declares, “We gotta go. We can talk in the car.” Up and out, on to the next event.

Thanks in part to his speed, Sage was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles in 1971, after a starring role as a defensive tackle at Louisiana State University. But he chose graduate school over the pros. Armed with an MBA, he returned to Houston to make his fortune in commercial real estate development. By his mid-30s, he was a millionaire adept at asking wealthy investors to back his ventures.

After his sister’s murder, however, Sage lost his way. “I was one angry dude,” he says. “It took me to a dark side of life that I had never been.” Years into what he calls his “valley experience,” he plotted an escape. A lifelong Catholic, he dove into Bible studies with newfound fervor. Sage’s faith served as a release valve for the despair that had built up inside him in the years after Marilyn’s murder. He also began looking for a cause he could adopt, in the hope of replacing his anger with something constructive. A victim services caseworker from the state of Texas told him about a faith-based group working inside prisons to reform the lives of inmates. The group was the Sycamore Tree Project, an offshoot of Watergate felon Charles Colson’s Prison Fellowship organization. Sycamore grounds itself in the Christian belief in redemption and practices a form of restorative justice, a philosophy that stresses interpersonal healing over state-imposed punishment as a response to crime.

Sycamore’s particular niche in prisoner rehabilitation is using victims of crime as counselors who teach prisoners to appreciate the harm they did to their victims, and to their own families. Though some forms of victim-offender dialogue put criminals in a room with the person they harmed, Sycamore uses surrogates. By pairing prisoners with other offenders’ victims, the program avoids the intensive preparations needed to avoid a volatile confrontation, which in turn allows Sycamore to counsel far more prisoners.

Sage joined up, counseling prisoners and telling his story as a victim for about six months. He believed in Sycamore’s methods, but, despite his own devout faith, he worried that the group’s overt proselytizing would be more of a hindrance than a help in reaching as many prisoners as possible.

In 1998, Sage struck out on his own. Houston, especially in the high-crime 1990s, was not the time or place to find a deep reservoir of concern for prisoners. But by tapping his business connections and exercising a natural-salesman’s flair for fund-raising, Sage got Bridges to Life up and running with large startup donations from two wealthy benefactors. He built the program in increments: recruiting volunteers; raising money from an ever-wider circle of individuals, churches, and foundations; hiring staff; and winning access to prisons and prisoners.

Photo courtesy Mark Obbie

Bridges to Life now ranks as one of the largest program providers inside Texas’ massive prison system, operating a low-overhead operation on an $800,000 annual budget. More than 500 of its volunteers work in more than three-dozen Texas prisons and in satellite programs in several other states. Some 4,000 prisoners graduate from its programs each year.

The teaching is labor-intensive. In mass meetings and 10-student breakout groups, victims give talks and group leaders prompt each prisoner to tell the story of his crime. Along with weekly reading assignments and homework—sample study question: “List some specific things you can do to make amends or pay back”—prisoners write letters of apology to their victims and their families. (Only the family letters get mailed, due to standard prison prohibitions against offender-victim contact.) The tone Bridge’s volunteers take in addressing prisoners is nonjudgmental but brutally candid, in an effort to push them to take full account of their wrongdoing.

Sage stresses that his program embraces prisoners from any faith, and no faith. “I really think you gotta meet ’em where they are,” he says. “I would not call us a Christian organization, because if we did that then we’d be limiting our clientele. They understand it pretty quickly.” And yet evangelical Christianity motivates many of his donors, nearly all of his volunteers, and many of the prisoner-students.

The program has removed volunteers from the classroom for violating a ban on proselytizing. But proselytizing is written into the textbook: “Belief in God is critical to success in the Bridges to Life experience,” it reads. Sage himself frequently characterizes his work as “God’s will for my life” and “a ministry.”

“It’s not perfect,” Sage admits of his attempt to balance his faith with his desire to welcome all comers. “We’ll be talking about that 10 years from now.”

* * *

John Sage claims that prisoners who go through his program behave better during the remainder of their sentences and, once free, commit new crimes less frequently than the average ex-con. Reciting his donor-friendly pitch, Sage says, “We enhance public safety. We make your community a safer place.” Both claims have anecdotal evidence to back them. But the statistical evidence is slim: There’s no proof that his program improves prison discipline, and very little that it reduces recidivism.

In the most recent study of a large group of Bridges to Life graduates, the three-year recidivism rate—those who returned to prison within three years of their release—was 14 percent. That rate is substantially better than national recidivism averages of 40 percent to 75 percent, depending on the study and the time span from release date to new offense.

But selection bias puts a large asterisk next to Sage’s numbers. Participation in Bridges is voluntary, and the recidivism rates could well be skewed because the prisoners signing up for the program were predisposed to fly straight. It’s a criticism often made of other faith-based programs’ measurable results.

Sage and Kirk Blackard, a retired oil executive who wrote the program’s teaching materials, concede as much about the data. But Sage points to survey results of graduates showing marked changes in attitudes: a resolve to turn their new awareness of the harm they caused into a commitment to behave more responsibly when they get out of prison. And he challenges the notion that prisoners who entered his programs were destined for success, noting that the program’s original preference for inmates on the verge of release has been broadened to any prisoner other than sex offenders and the severely mentally ill, including those with many more years left on their sentences. “We take on anybody they give us,” he says. “A lot of the guys don’t even know why they came. They’ll have a buddy sign them up. They want to get to the air conditioner. They want donuts and cookies.”

When talk of statistical validity begins to bore the hyperactive Sage, he falls back on faith in his creation, and what he sees and hears whenever he visits a prison: “We’re still helping a lot of people,” he says. “We’re still seeing the change. We know that it’s affecting them.”

To illustrate his point, Sage has arranged for me to see two graduation ceremonies, on back-to-back nights, at Jester I and III, two units in a cluster of prisons on the southwestern fringe of metropolitan Houston. The main event is an open-mic time when prisoners tell each other, and tell the volunteers who’ve turned out for the final session, what the program has meant to them.

Photo by Tim Mitchell

During a thorough pat-down by sullen Jester I guards in a broiling late-afternoon sun, Sage welcomes volunteers with bear hugs. Now 67, Sage shows no signs of slowing down as he makes a last-minute run for ice and helps a frazzled colleague lug juice containers and snacks for the graduation party. As the Bridges entourage makes its way past razor-wire-topped gates to the room set aside for the ceremony, we pass a sign: “Hands behind back. Eyes forward. No talking.” The oppressive mood breaks once we’re in the room and the prisoners enter, greeting their teachers with hugs and smiles despite the stifling heat. (Texas’ prisons are well-known for lacking air conditioning.)

Before open mic, the prisoners hear from Sage. Ever the promoter, he runs down facts and figures demonstrating Bridges to Life’s growth and success, speaking to this room of tattooed inmates as though it’s a meeting of shareholders. Next come three sets of prisoners performing music, one of whom is a feeble and toothless old man who belts out an astonishing gospel number in a high-lonesome a cappella.

After a welcome from the prison warden, it’s time for prisoners to speak. For today’s exercise, Sage lays out the ground rules: Don’t repeat the story of your offense. That’s for the private group meetings. Don’t run over a couple of minutes. And “speak from the heart.”

Sage has likened his role to “garbage remover,” and it’s in moments like these that his analogy makes sense. He’s encouraging prisoners to open up about, and then shed, the shame that weighs them down and robs them of the hope that they can change. He and the other victims who counsel these prisoners let them know that they are not here to be judged. Rather, they are entrusted with a duty to be honest about their failures. The entire program is about coaxing that accountability out of them. Now it’s time for a bit of religious-revival-style testifying.

The men, clad all in white short-sleeved cotton shirts and slacks, quickly queue up to take their turns. After introducing themselves by their first names, many thank Sage, the victim speakers, and the warden making this program possible. Then, one after the other, they bare their regrets.

“I knew one thing when I got here,” says a pudgy, middle-aged man, John Robert. “I’ve done wrong. I hurt myself and I hurt a lot of people along the way. I knew that. It was a dark shadow over my life. When I got to Bridges to Life, I learned to deal with that hurt that I caused other people and I caused myself.”

A man calling himself “Blackstone” thanks the victim in his group for telling his story of loss. “It’s all I could think about for the next few days,” he says. He and another man in his group confided in each other that they were nervous about sharing their stories. “I told him I was ashamed for my past, for what I had done,” he says. “Come to find out, his story was almost identical to mine. It was almost identical.” Realizing they were not alone emboldened them to open up to their group. “That’s when I was able to start to forgive myself,” Blackstone says.

An older man who doesn’t give his name speaks in a halting voice: “I’ve been abusing family, friends, and myself for many years,” he says. Now, he wants to re-establish a connection to his adult daughters, one of whom is married and has two children “who I’ve yet to meet because she’s embarrassed or ashamed to have me as a dad.”

Vernon, a hard-looking man who identifies himself as an alcoholic and drug addict, talks about being a burden to his family. Bridges to Life, he says, taught him to grow “into the man that I want to be, the man that I could have been a long time ago.”

After dozens of speakers, the meeting breaks for group photos and a reception of sweets and juice. Prisoners usually deprived of snacks pile flimsy plates high with cookies and mingle with the volunteers. Standing in the middle of the din is Warden Monty Hudspeth, holding forth on why he’s such a fan of Bridges to Life and other faith-based programs—and demonstrating that he pays no heed to the Bridges to Life playbook discouraging proselytizing. Prisons, he offers, “should be prayer houses” devoted to “moral rehabilitation, completely changing the man from the inside out.”

Photo by Tim Mitchell

The next night, at Jester III prison, the routine is largely the same. Near the end of the open-mic segment, one elderly prisoner grunts with effort as he rises from his wheelchair to address the victims and other volunteers. “I had to stand up because y’all stood up every week that y’all came. Y’all stood in a way that most people don’t stand. You know, people on the outside, they look at people in the prison and they say, ‘Well he did this, and he could do that. I’m not gonna be around them. I’m not going to set by you.’ ”

“But y’all put all your hard feelings behind you. You put all your emotions aside. And you came through that gate. And you didn’t act better than me. You didn’t act smarter than me. You see, y’all showed something that people don’t show every day.” With that, he asks the volunteers, “Would you please stand up?” Then, at his invitation, the crowd of white-clad inmates gives the volunteers a standing ovation.

* * *

Only certain victims of crime will ever find themselves volunteering for a program like Bridges to Life; Sage takes pains to avoid painting those who won’t as uncaring or vindictive. Victims’ needs vary, and they change over time. But that makes recruiting hard. Other than fund-raising, Sage’s chief worry throughout the years has been finding enough victims willing to show up all 14 weeks to run the classes, or at least to appear once during a program as a featured speaker. As Bridges has grown, the number of victim volunteers has remained fairly constant, which means that victims’ share of the volunteer workforce has fallen, from about 80 percent in the early years to about one-third lately.

To avoid further erosion in those numbers, Sage has refined his sales pitches to volunteers, using only those that consistently resonate. Do it to enact the Christian belief in redemption. Do it because you want to prevent crime and spare others the pain you have suffered. Do it because you crave the relief you feel when you try to make sense of what happened to you by telling the story of your trauma. Do it because criminals need to hear how the devastation from one crime can ripple for decades through victims’ lives.

It was that last summons that worked on Maria Reyna, but only after she floundered on her own for many years. In 1986, Reyna was raising three young children alone in Houston after dumping her husband, Tony Flores, over his cheating and drug use. That hadn’t stopped him from abusing her, however. After one beating, she found him back in her apartment, vowing to kill her father. Reyna’s father, a former Mexican police officer, showed up armed and ready for a fight. In the wild shootout that followed, Reyna shielded two of her children while their father executed their grandfather in front of them. Reyna’s brother suffered life-threatening wounds as well.

Flores served 17 years of a 50-year prison sentence for murder and attempted murder. Near the end of his term, Reyna talked to him in an effort to impress on him how much he had hurt the entire family. She wanted to see him express real remorse. But Flores remained unrepentant. Despite the presence of a trained mediator, who tried to help Reyna get what she came for, the exercise proved fruitless.

The pain she wanted him to appreciate went beyond the loss of her father. In the aftermath of the killing, one of her brothers drank himself to death. Other members of her family took their bitterness out on Reyna for having brought Flores into their lives.

She couldn’t help but think they were right to blame her. Those feelings of guilt led one night to contemplating the unimaginable. “I just couldn’t stand it anymore,” she says. “I felt like I needed to do something and just get rid of my life and my kids’ lives.” Lying on a bed with her two youngest, she fingered a telephone cord while thinking of strangling her children. Instead, she says, “I put that cord down that night and just fell asleep.”

She had walked back from the edge, but her prospects remained bleak. She and her three kids lived in the projects on public assistance. “I just couldn’t get it together,” she says. She remarried and had a fourth child. But that marriage didn’t last, either.

Photo courtesy Mark Obbie

In 2009, the mediator who conducted Reyna’s failed talk with Flores asked her for a favor. Would she go with him into prison to tell her story to a Bridges to Life class? By that point, Reyna doubted that more talk about that terrible day and its aftermath would do her any good. But she felt she owed it to the mediator, so she agreed.

While describing to prisoners a scene of terrifying violence and a legacy of family devastation, Reyna felt a surprising calm. “There was so much deep, deep down inside my heart that I needed to bring out,” she explains. She signed up to give the talk more often. Then she volunteered to lead classes herself.

Her mother couldn’t grasp why she would want to do that. Reyna would respond, “Mom, don’t question me. I’m not doing this for you. I’m doing this for God. This is where God wants me to be. This is where God wants me to tell my story because these people need to know what we have gone through.”

When telling her story inside prisons, she spares no details: her husband’s abuse, a blow-by-blow description of the murder, the fallout in her family, her own paralyzing guilt and despair. Prisoners tell Reyna of the regret her story has uncovered in them, often through tears. “They start thinking about their family members,” she says. “And then they think about themselves.”

It’s not just about what the prisoners need from her. Reyna sees her volunteer work as a way to turn her own focus away from her ex-husband. “This is about me and about trying to help other people,” she says. Telling her story helps “clean out my soul and my heart,” she says.

Reyna, now 53, keeps updating her story as her life changes. She wants the prisoners to hear this, too. First there’s the news that she reconciled with her family, and that her children grew into successful adults. Reyna works with two of her sons at a mortgage-lending firm run by her daughter.

The latest update is more bittersweet. Before her mother died last summer, she told Reyna she was proud of her. “Because I was an amazing child to her,” Reyna says, her eyes shining. “That’s what she told me. And she said, ‘Every trial and tribulation the Lord brought to you, you were a fighter. And you never let nothing bring you down. You’re still standing.’ ”

* * *

John Sage launched Bridges to Life while his niece Kelley Watts was living in New York, after getting her bachelor’s degree. She later returned to Houston for graduate school but remained uninvolved in Sage’s prison work. She was proud of her uncle’s accomplishment, but she wasn’t ready to commit to helping.

Marilyn Sage Meagher at her surprise 40th birthday party, about three years before her death. Photo courtesy Meagher's family.

After leaving the area again, marrying, and having a child, Watts returned once more to Houston in late 2013. That gave Sage another opportunity to recruit her to his cause. She began tentatively, giving brief talks at luncheons and fund-raising receptions. Then she gave in to Sage’s entreaties and began telling her story in prisons.

Watts finds it easier in some ways to talk to prisoners than to potential donors. To the donors, she lauds her uncle’s work and makes high-minded points about taking responsibility for the kind of society we want to live in. But, she says, “I almost found that more difficult, to talk around it but not talk about it.”

“It,” of course, is the trauma she experienced and still lives with. It’s the horror of discovering her mother’s fate by stepping in a pool of blood in a dark apartment. And it’s the story of a vivacious, unpretentious mother of two and sister of seven who might only remain an abstraction to the prisoners if not for her daughter’s tribute.

Watts says she’s still searching for her place in Bridges to Life. Because she keeps busy with her new therapy practice and raising a toddler, she isn’t quite ready to devote 14 weeks at a time to run her own Bridges to Life classes. The most she can manage for now is to appear once per course, about half a dozen times per year, as the featured victim speaker. She’s also helping Bridges to Life seek donations from young professionals.

She is clearer about what she can do for Bridges to Life than about what it can do for her. Unlike many of her fellow volunteers, she lacks the evangelical pull toward forgiveness and belief in redemption. “I don’t feel like it’s mine to forgive,” she says, adding that her faith is “probably a bit more eclectic” than her uncle’s.

She doesn’t experience the talk-therapy benefits that other prison volunteers get from telling their stories. “I don’t know if it’s helpful,” she says. “I don’t need to talk about it anymore, but I can sit and talk about it for as much as anybody needs.”

It’s only when a long conversation turns to her preschooler that Watts’ emotions get the better of her, and she begins to cry. Her son Sterling was born shortly before Watts and her husband moved back to Houston. Next November, Watts will turn 41, nearly Marilyn’s age when she died. Having a child has made Watts see her own mother in a new light as she thinks about the kind of mother she wants to be. “It makes me miss her more,” Watts says. But it’s not a setback. She’s found a new connection.

This is the second in a series of articles on the victims of crime and the ways in which we fail them by focusing criminal justice on harsh punishment alone. Sign up for alerts about future installments below.