He Killed Her Daughter. She Forgave Him.

Linda White believes in a form of justice that privileges atonement over punishment. She practices what she preaches.

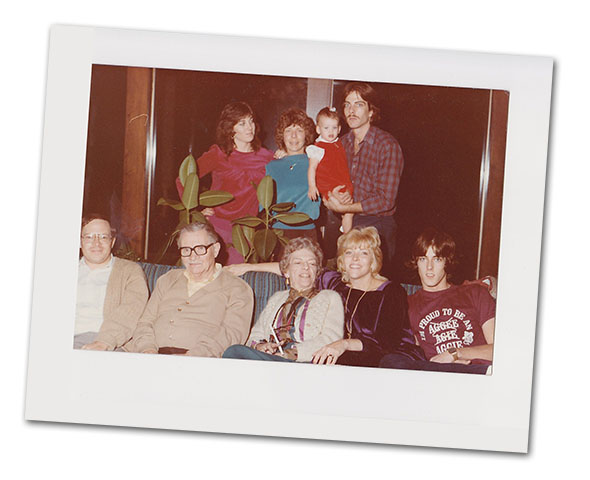

Linda White, left, bottom row, and Cathy O’Daniel, second left in top row. Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Linda White.

Final conversations between murder victims and the family members they leave behind have a way of becoming the subject of lifelong regret. Words not spoken or last moments wasted on the trivial can harden into a lasting memory of love left unexpressed. John and Linda White were spared that burden.

The middle of their three children, Cathy O’Daniel, had stumbled through adulthood—there was an unplanned pregnancy, a rushed marriage, divorce, struggles with alcohol. But by age 26, she seemed to be righting her course. Cathy confided to her mother that she was expecting her second child and intended to marry the father, a doctor.

When the couple returned from a trip out of state in November 1986, they dropped by the Whites’ suburban Houston home for dinner so Cathy could introduce her parents to her new beau. The four of them sat around the kitchen table for a relaxed conversation. After the young couple left for the evening, the Whites realized a remarkable coincidence. Cathy’s fiancé was the son of the doctor who had been her pediatrician, back when the Whites had lived in Colorado. It was after 11 p.m., but Linda was too excited to wait to tell Cathy of her realization, so she called her. “And that was the last conversation that we had,” Linda said recently. “But we were laughin’.”

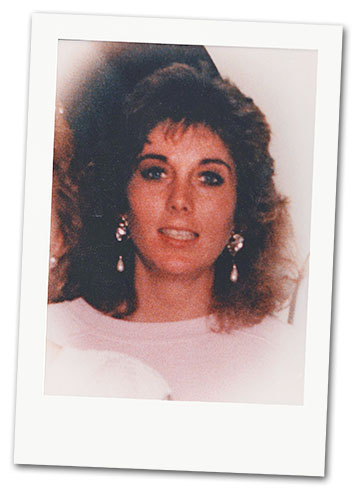

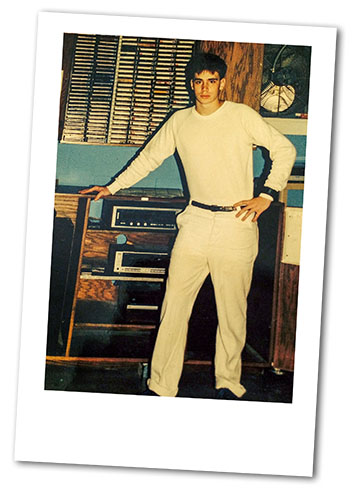

Cathy O’Daniel. Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Linda White.

Days later, John and Linda sat vigil at the same table, hoping for encouraging news about their daughter, who had suddenly disappeared. One of the many calls the family received during the four agonizing days she was missing was from a 15-year-old named Gary Brown. Brown called anonymously to assure the family that Cathy was safe but needed time alone to sort out some personal issues. The call was a cruel ploy, Brown’s attempt to buy himself time. He and another 15-year-old named Marion “Marvin” Berry had already abducted Cathy, raped her, and shot her to death.

The boys, who were arrested days later with Cathy’s car northeast of Dallas, had been stealing and drugging their way around a large swath of Texas after escaping from a Houston rehab center. They had few belongings. Found on Brown at his arrest were a rosary, a Bible, two packs of cigarettes, and no money. In due course, both boys admitted Cathy was dead and blamed each other. They had happened upon her at a gas station, where they’d been marooned when their stolen car broke down. Brown led police to her body off a remote dirt road.

“For three weeks, I was just numb,” Linda White told me, at that same kitchen table. “I mean, just stark, staring, sitting right here like this, lookin’ out the window like this, smoking as much as I could smoke.”

The boys’ criminal case plodded on through 1987, but the Whites paid it little mind, as a draining custody battle with Cathy’s ex over her daughter, Ami, took priority. Certified to be tried as adults but ineligible for the death penalty because of their age, Brown and Berry eventually took plea deals: 55 years for Berry, 54 for Brown, who held out longer for his deal.

The Whites felt the sentences were adequate and, having won custody of Ami, they were glad to be spared a prolonged trial. “We didn’t ever have to see them,” Linda White says. “We didn’t have to think about them anymore. And for a long time we didn’t.”

In the first months after Cathy’s murder, the Whites sought out the comfort that they hadn’t found at the courthouse. They joined a Houston chapter of Parents of Murdered Children, drawn by the group’s mission to create a place where parents who share a terrible bond can provide emotional support to one another. At first, it worked. The Whites felt understood in a way that they didn’t among family and friends. “We know how you feel,” they heard again and again at POMC, and it helped.

But the group, like many victims groups, has another mission as well: advocating tougher punishment, including longer prison sentences and restrictions on parole. White adopted POMC’s views as her own. She even agreed to appear in a video in which she advocated for lowering the death penalty age to 13. Soon, though, the meetings’ emphasis on punishment started feeling to White like a hollow promise. “I didn’t feel like anyone was talking to me about healing, about moving forward. It was just about getting even,” she says.

On the way home from one meeting, John turned to her and said, “Where do they get the energy for all that bitterness and anger?” The comment snapped White into focus: “I didn’t want my life to be like that,” she told me.

But what did she want her life to be? After quitting high school at 17 to marry John, White had three children in quick succession. Parenthood kept her busy enough when the kids were young. When they were a bit older, White took a correspondence course to study for her GED. After passing with high scores, she enrolled in classes at a college in the Rio Grande Valley, where the family had moved for John’s work.

She was well short of a degree when the family moved again to Magnolia, Texas, in what then was mostly pastureland north of Houston. White’s education remained on hold. “I did a lot of lunch,” she recalls. “I did a lot of card playing.” At that last dinner with Cathy, White’s daughter teased her middle-aged mother. “Mom doesn’t know what she wants to be when she grows up,” she said.

With Cathy gone, White mapped out a new future for herself. She would return to college, at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas. After completing her bachelor’s degree in psychology, she stayed on at Sam Houston for a master’s. She hoped for a career as a death educator, providing grief counseling. Her academic focus had obvious roots in her own experience, but White says she sought something more than therapy in her work. She craved a deeper understanding of how people cope with traumatic loss. Eventually, she realized her hunger for knowledge and love of teaching were stronger than her desire to counsel patients. “It was healing for me,” she says, “I had purpose.” She decided to pursue a doctorate.

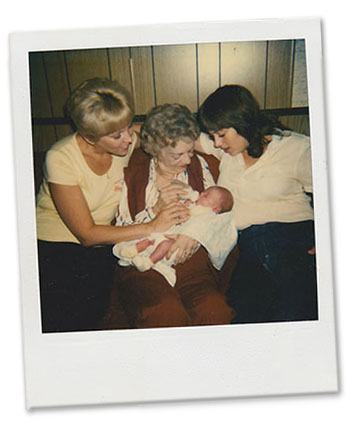

Linda White, left; her mother, holding Ami, Cathy O’Daniel’s daughter; and Cathy O’Daniel. Photo courtesy of Linda White.

As a grad-student teacher, she took on a heavy load at Sam Houston and at a local community college. One day, while teaching at the community college, her students started talking about Susan Smith, the South Carolina woman then in the news for drowning her two young sons while setting off a frantic search for a fictitious carjacker-kidnapper. The students’ reactions shocked White. “They wanted to string her up,” she says. “Actually, they wanted to kill her the way she killed her boys.”

“I looked at the expressions on their faces, and I decided that was violence,” she says. “Everything going on that day in that discussion, in that classroom, was violence. There was no one being struck, but there were violent thoughts and violent words. And I just was incredibly uncomfortable with it.”

The reactions revived the sense of alienation White felt among other parents of murder victims years earlier. “Why is it,” she wondered, “that everything is about bringing people down, punishing, adding more suffering to the world?”

The victims’ rights movement emerged in the 1970s and ’80s from three separate strands, according to prominent victims law scholar and advocate Paul Cassell: civil rights activists frustrated by a law enforcement regime that didn’t take crimes against black Americans seriously, feminists seeking fairer treatment of rape and domestic abuse victims, and law-and-order advocates opposed to the Warren court’s civil liberties rulings. While these causes cut across ideological lines, their advocates shared a common demand that the justice system show crime victims more respect. They succeeded fairly rapidly, as states scrambled to pass legislation and constitutional amendments instituting tougher penalties for crimes like spousal abuse and drunk driving, as well as rape shield laws.

Victims also won a place at the table. In the past, they had been relegated to an ancillary, largely silent role in the clash between the state and the defendant. Now prosecutors kept them informed about plea bargains. Judges heard from them at sentencing. Parole authorities notified them when it was time to decide if offenders should be released and took note when they objected.

The system was listening to victims, but it really only wanted to hear one thing: Victims want retribution. In an era of growing public alarm over street crime and drugs, victims’ advocates were heard most readily when they spoke in unison and with a tough-on-crime message. Victims who sought something other than the harshest prison sentences were ignored or marginalized.

Today, when even mainstream conservatives concede it’s time to rethink the policy excesses of the wars on crime and drugs, victims serve as one of the last voices for the throw-away-the-key school of criminal justice. When Sen. Charles Grassley, now the Judiciary Committee chairman, successfully stymied the most modest form of federal sentencing reform under debate in the 2014 Congress, he did so in part by arguing that any cuts in mandatory minimum prison terms equate to “cost shifting from prison budgets to victim suffering.” Last year, when Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette announced his opposition to reconsidering life-without-parole sentences for children, he put the victim argument front and center. “The integrity of our justice system demands crime victims and their families come first,” Schuette said.

To victims’ advocate Anne Seymour, such tactics demonstrate how outsiders impose their assumptions on victims instead of really listening to what victims say. “We paint victims with this brush, that they’re all the same, and they’re not,” Seymour says. She counted herself as a typically tough-on-crime victim advocate in her earlier days. Now she travels the country for Pew Charitable Trusts’ Public Safety Performance Project, collecting policy ideas from other victim advocates. Making assumptions about victims’ views, she says, is no different than not bothering to consider their interests at all.

Law-and-order conservatives don’t deserve all the blame. Criminal justice reformers habitually avoid any mention of victims when pushing for better treatment of defendants and prisoners, as if victims’ interests could not possibly be served by such reforms, and the less said the better. Like their adversaries, they tend to view criminal justice policymaking as a simple binary: pro-defendant or pro-victim, but not both.

As for the criminal justice system itself, it is not a welcoming place for victims who don’t walk the party line. Victims from time to time speak out against the death penalty or urge reconciliation and forgiveness, usually after the passage of time, after their desire for vengeance has ebbed. In the rare cases when this happens before criminal cases have been resolved, victims typically find themselves at odds with prosecutors, who are conditioned to seek maximum punishments. The result can be a respectful brush-off (as in the prosecutor’s response when a Boston Marathon bombing victim’s parents opposed the death penalty for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev) or open antagonism (a Colorado judge last year blocked a family’s attempts to formally oppose execution of their son’s killer).

Forgiveness of the sort expressed by the Charleston, South Carolina, massacre victims’ families at Dylann Roof’s bond hearing can astonish us with its grace. But the angry-victim archetype is so ingrained that such victims often see themselves portrayed as outliers whose religious beliefs or personality quirks compel them to repress their natural impulses. Occasionally, however, a victim makes us consider the possibility of something else—a different definition of justice.

Among the readings that Linda White assigned herself in her search for alternatives to retribution was a slim booklet by a United Church of Christ minister, Virginia Mackey, on an approach called restorative justice. Instead of only asking which laws were broken, who broke them, and how much punishment they deserve, restorative justice asks who was harmed and what must be done to repair them. The focus shifts from offender to victim and from punishment to whatever makes things right.

White found the idea compelling and better suited to her own experience as a victim. She pored over bibliographies and footnotes, one book or article leading to a new pile of reading. Her reading introduced her to the restorative technique called victim-offender dialogue. Since the earliest days of restorative justice in the 1970s and ’80s, dialogue has been at the core of its practices. Used most often in juvenile matters for relatively minor cases—theft, vandalism, school discipline—the idea is to sit victims and offenders face to face, along with a mediator.

Mediated dialogue promises a victim the opportunity to get his questions answered and to tell the offender of his loss and pain. The offender apologizes and promises specific ways to make amends, often a combination of restitution and acts of atonement and rehabilitation, such as community service and drug treatment. Extensive evidence supports claims that the method improves recidivism rates by holding offenders directly accountable to their victims.

Victims seem to appreciate the process as well. Mark Umbreit, a restorative justice advocate and researcher at the University of Minnesota, has been writing for nearly 30 years about the failures of retribution and the merits of dialogue to help victims heal. In his book Restorative Justice Dialogue, co-authored with Marilyn Armour of the University of Texas, Umbreit points to 85 studies documenting victims’ satisfaction with the process as “consistently high across sites, cultures, and offense severity.”

In one of their own studies, Armour and Umbreit interviewed family members of murder victims in two states and attempted to measure the healing they experienced when offenders got maximum sentences. They concluded that although most survivors wanted to see killers punished to the utmost extent of the law, the benefits of such sentences proved elusive: The families, particularly in death penalty cases, felt stuck in limbo during years of appeals, while death and life-without-parole cases alike left victims’ survivors with a nagging sense of unfinished business because so many of their questions went unanswered.

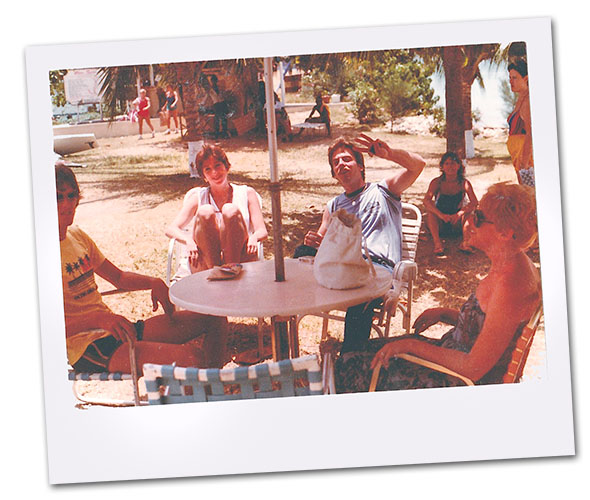

Cathy O’Daniel, second left. Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Linda White.

What’s truly beneficial to victims, they found, was restoring their sense of control over their lives. One way to do that is through direct dialogue, eliminating the distance between survivor and offender that the adversarial criminal justice system imposes. It’s that distance—borne of ritual denials of guilt, antagonism between defense and victims, and defendants’ frequent refusal to testify—that keeps the trauma alive. Instead of hearing the full story from a defendant, or an apology, survivors are left to imagine what the offender did or thought.

When White first discovered this parallel universe in the criminal justice world, her reaction was more scholarly than personal. By this point, in 1997, she was in a Texas A&M University doctoral program in adult education. Now she knew what she would research for her dissertation. “Imagine,” White says, “learning about a whole new world at 57.”

The thought of studying other victims’ experiences, and even entering prisons to talk to inmates, didn’t faze her. She was already teaching some of her Sam Houston classes to inmates inside the prisons that dot the landscape around Huntsville. She had heard prisoners express remorse for their crimes and wished their victims could hear those words directly.

It was also at this moment that she decided she wanted to experience restorative justice for herself. It was an auspicious moment to try. Texas’ official victim services agency had begun conducting mediated victim-offender dialogue inside prisons in 1995. The program already was one of the largest of its kind in the country and has remained so ever since. A decade after Cathy’s murder, White decided to seek face-to-face meetings with Marvin Berry and Gary Brown.

Linda White knew who should mediate her meeting with her daughter’s killers. White had met Ellen Halbert while teaching in prison. The two had much in common. Just months before White’s daughter was murdered, Halbert was the victim of a nightmarish home invasion and rape. Halbert had turned her experience into a career: as a victims’ rights advocate, director of victim services for the district attorney in Austin, and as the first crime victim appointed by a governor to serve on the Texas prisons’ powerful board of overseers. Though she had used her influence to steer the mediation program’s launch through powerful headwinds in the prison system, Halbert had never served as a mediator herself. She told White she would do it.

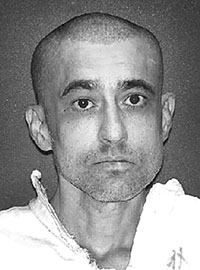

Courtesy of Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Halbert learned that prison officials would not allow a victim mediation with Marvin Berry. By that time, Berry had a string of run-ins with guards and fellow inmates that would only grow more violent in future years. Just five years into his 55-year sentence, he received another 12½ years for possession of an improvised knife.

State officials deemed Brown a good candidate for the process, however. With a clean record during his first decade inside, he met the most important criteria for mediation: He admitted his guilt, was remorseful, and was willing to tell the full story of the crime as one way of making amends to his victim’s family.

Around this time, filmmaker Lisa Jackson met Halbert. “I was really taken with Ellen,” she says. “And she told me about this victim-offender mediation program.” Jackson asked Halbert for help in filming a case, if they could find the right one and get permission. “Well,” Halbert remembers responding, “I’m getting ready to do a mediation. How about that one?”

Playing off the state’s pride in its pioneering program—a rare bit of positive news for a prison system long under siege for overcrowding and brutality—Halbert helped Jackson navigate the politics of getting camera access, not just to the prison but to the preparations leading up to the mediation and to the mediation itself. Blessed with a helpful warden and victims’ services staff, Jackson and her small team cleared the bureaucratic hurdles while Halbert counseled White, Brown, and the White family in multiple training sessions to prepare them for an undoubtedly wrenching experience.

White’s family was torn. Her husband, John, and two sons decided they wanted nothing to do with meeting Brown but wouldn’t stand in the way if White wanted to go through with it. White wasn’t alone, though. Cathy’s daughter, Ami, who was 5 when her mother was murdered, was now a young woman. She wanted in.

Jackson had found a compelling cast of characters for her film: Linda White, in Jackson’s words, “the nice-nice Texas woman” whose mission is to make everyone comfortable; Ami White, personable and vulnerable; Halbert, skilled at good-ol’-boy talk with the warden and guards and, in the next moment, coaxing Brown to open up for the first time about the details of his crime. Finally, Brown himself, by then an inmate for 14 years, his still-boyish face a permanent mask of shame and pain.

The cameras followed Halbert as she prepared Brown and the Whites for their meeting. On the eve of the mediation, one camera recorded an uneasy dinner conversation at the Whites’ in Magnolia while, more than 300 miles away in Wichita Falls, Texas, another followed Brown through his daily routine up to and including bedtime in his cell.

The meeting between Brown and the Whites lasted four hours; Jackson edited it down to 13 minutes for her 43-minute film. From the moment Brown meets Linda and Ami White, he’s crying, unable to make eye contact. Under her breath, Linda White murmurs, “I can tell it’s gonna be kind of a tough day.”

By then the Whites had learned more about the murder and murderers: how, for example, the boys tried to mutilate Cathy’s face in a vain attempt to hide her identity. They’d also learned more about Brown, about the lifetime of petty crimes and physical, sexual, and substance abuse in his childhood.

But in their meeting with Brown, they learned still more. How he and Berry tricked Cathy into giving them a ride; ordered her down a road “leading to nothing,” in Brown’s evocative phrase; raped her at gunpoint; shot her in the leg to “slow her down” so they could escape, only to decide—after discussing it in front of her—to eliminate the witness to their crimes altogether.

Then comes the most devastating revelation in the film, prompted by a question from Ami about her mother’s last words. Through tears, Brown explains how Cathy urged them to leave with all her belongings and promised not to report them. “And then as Marvin pointed the gun towards her, she said, ‘I forgive you, and God will, too.’ And then she put her head down.” Everyone in the room is crying now. Linda and Ami cover their faces. Then Linda hugs Ami and says, “That was your mama. Down to the very last moment of her life.”

Cathy O’Daniel and her daughter, Ami. Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Linda White.

Brown makes no excuses during the encounter. Not about his catastrophic upbringing. Not about being too high to know what they were doing that day. Not to stress that it was Berry who pulled the trigger. And the Whites get to make the points they came to make, about Cathy’s life. They show Brown photos of his victim. Ami talks about her struggles growing up without Cathy. They also have the chance to convey to Brown that his resolve to live a better life is the only atonement he can make and all that they ask of him.

When it’s time for goodbyes, the three stand. After some encouragement, Brown puts his arms around the two women, breaking into a relieved grin, to pose for photos. Linda then hugs Brown, telling him in a caring tone, “We’ll be watching you.” Ami follows suit with a hug.

Jackson’s film Meeting With a Killer aired on Court TV in November 2001. In the years since, it has been a staple of prisoner counseling sessions in Texas. A faith-based private program, Bridges to Life, brings White into prisons several times a year to screen the film and then take prisoners’ questions. Her appearances, like those of other victim volunteer counselors, aim to teach empathy through stories of loss and pain.

The approach sounds simplistic, but to White such counseling with victims is a necessary step toward prisoners’ re-entry to society—and often the first time prisoners have directly confronted the harm they have caused. “The toughest thing they can imagine would be to sit across the table from a family member of their murder victim,” she says. “It was just much easier to sit in prison and do their time.”

As the film drew attention—White made appearances on Oprah and the Montel Williams Show—more prison-counseling programs around the country, and then worldwide, used it for training. Sometimes, White attended screenings for a Q-and-A, her appearance accompanied by a local news story about her experience. At one criminal justice conference, a man approached Halbert and said, as she recalls, “I’m so glad to meet you. You know you’re a movie star in prisons in Finland.”

White used her new renown to preach forgiveness and spread the restorative justice gospel. She broadened her advocacy to oppose the death penalty and life-without-parole sentences for juveniles.

At home, the agenda wasn’t as clear-cut. Ami later admitted to Jackson that she regretted hugging Brown. She wasn’t quite ready for that but had been caught up in the moment. She continued to struggle emotionally, as did White’s two sons. White remains guarded when talking about her family, but it’s clear that the murder still figures prominently in their lives. White and her husband, now in their 70s, have custody of Ami’s youngest child, a 7-year-old daughter, and also help raise her 15-year-old son. “Raising my third generation of children,” White sighs. “And some days it’s harder than others.” Ami declined numerous requests for an interview.

Cathy O’Daniel, top row left, and family. Linda White, second right, bottom row. Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Linda White.

In the more than 13 years since the film’s release, John White has never watched it. “As soon as Gary comes on the screen,” Linda White says, “he gets upset.” The couple, married 57 years, allow each other the privilege of grieving differently.

For nine of those years, Gary Brown remained in prison. He was allowed to see the film once, alone, in a chaplain’s office.

Brown’s cooperation in the mediation could not be used to bolster his case for early release; the rules of the Texas mediation program bar it. But thanks to a fluke in timing—he was sentenced before life-without-parole sentences came into vogue and was eligible for early release under a law Texas passed to ease prison overcrowding—Brown left prison after serving 23 years and five months, less than half of his original sentence. He was released to a halfway house in Beaumont, Texas, in May 2010. (Berry’s frequent, violent encounters with guards and other inmates have extended his projected release date to 2051, when he will have served 64 years.)

Initially, White had only sporadic contact with Brown, by letter, phone, and text. (He wasn’t allowed to use email or the Internet while in prison and continues to be prohibited from using them while on parole.) Just to stay in touch with White required a written plea to the prison’s victims’ services office and some help behind the scenes from Halbert to overcome rules barring prisoners and parolees from any contact with their victims. Says White, “I let them know that we had a relationship, and that I wanted to continue it.”

Gary Brown and a fish he caught soon after his release from prison in 2010. Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Ellen Halbert.

Through their correspondence, White learned of Brown’s struggles to get jobs and a driver’s license because he lacked a birth certificate. She asked for help from Bryan Stevenson, a prominent criminal justice reform advocate she had met in her own advocacy work. Stevenson says that it’s a common problem for people like Brown, who come from chaotic, neglectful families and spend much of their lives locked up, to lack birth certificates. With the help of Stevenson’s organization, Equal Justice Initiative, the document soon landed in Brown’s mailbox.

Other than that, White and Brown’s contact was largely limited to occasional updates and pleasantries. Just months after Brown’s parole, White told me she was committed to playing a role in Brown’s new life on the outside. She even expressed hope that they could go on a speaking tour together, to counsel young people to stay out of trouble. But in the first four years after Brown’s release, it didn’t happen. When I checked in periodically, she’d made no moves to arrange public appearances, nor had she made the 2½ -hour drive to Beaumont to see him. (Brown’s travel restrictions make it difficult for him to leave his home county.) When I asked why, White fumbled for an explanation. Other priorities had consumed her time, she said.

Finally, in early 2014, I decided to prod her toward a meeting that she said she wanted. I asked White if she would sit down with Brown if I came along. She agreed.

* * *

White wants to start the day, a Sunday, in her comfort zone: services at her church, where she was scheduled to deliver an inspirational talk to the congregation’s children. Plymouth United Church, a tiny progressive island in a sea of fundamentalist Houston-area mega-churches, proudly telegraphs its gay-friendly, socially conscious mission. But, settling into a chair facing ten rapt youngsters, White offers a lesson unburdened by politics. Using her ever-present smartphone as a prop, White talks about getting called by God “to love one another.”

White appears barely older than she did in the film in 2001: a little more gray, a few more wrinkles, but the same sunny face and piercing pale-blue eyes. She bustles about the church doling out hugs to anyone in her path. She now totes an oxygen tank, a constant reminder of her pulmonary fibrosis, which has grown progressively worse in recent years.

After a sermon by her ebullient minister, Ginny Brown Daniel, that includes a prayer for the thieves who stole the church’s lawn equipment that week (“They are indeed blessings from you”), White is ready for the trip east. On the drive to Beaumont, I tell White that I hope to find a quiet, private meeting place. But, prompted by a billboard on the interstate for a place called Catfish Kitchen, she announces she’s hungry. After a brief and awkward greeting at Brown’s apartment, we’re off to get some catfish.

Brown, tanned and fit at 43, is dressed neatly in new, loose-fitting jeans and a shiny polyester shirt that fails to hide a prodigious number of prison tattoos, including one that prominently features the word motherfucker. His thick hair verges on gray and is cut conservatively; his eyes are mournful, more worried than wary. Though he can’t normally afford to eat out, he knows right where to find Catfish Kitchen, on a bleak commercial strip off Interstate 10, popular with a diverse after-church crowd and big on fried everything.

Eager to please, Brown holds the car door open for White. His speech is full of “ma’am” and “sir.” He’s cautious, fidgety, which I initially take as an effort to let White set today’s agenda.

But as soon as we settled into our chairs and ordered the buffet, Brown takes charge. His opening question (“So, how have things been going for you in your life?”) elicits from White a transparently sanitized response—“Except for this,” gesturing to her oxygen tank, “really pretty good”—but Brown won’t let it go. He bores in, probing for signs that White and her family are still suffering because of him. Each time that White tries to lighten the mood with a critique of the catfish, or to turn the conversation to Brown’s post-prison accomplishments, Brown tacks back toward deeper waters.

Despite the din of kitschy country tunes, a hovering waitress, and raucous conversation all around us, Brown stares intently at White. He is crying. He acknowledges her forgiveness of him but says he can’t grant the same to himself. “You tell me, ‘Let go. Forgive,’ ” he says to her. “But I can’t say I’ve done that yet. I can’t.” White responds in her soothing drawl, “I know. We’ll keep workin’ on it, Gary. We’ll keep workin’ on it.” She reaches across the table to hold his hand. Now she’s in her element, the caregiver and peacemaker, more comfortable than when Brown asked her to revisit her own pain.

Gary Brown at 17, early in his 23-year prison stint, circa 1989, in the music therapy room of his psychiatric rehab prison. Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo courtesy of Ellen Halbert.

Brown shares little of his years in prison, from age 15 to 39, or of his many stints in juvenile lockups before that. He makes clear he’s here to show White what he’s made of himself outside of prison: continuously employed, paying his bills, deeply committed to his church. He agreed to say all this in front of a journalist, he says, to serve as an example to young people of the perils of drugs and street life and of the promise of redemption. “It’s the best I can give back to everybody,” he says, “so I welcome it.”

With each bit of evidence that he’s keeping the promises he made to White in their first meeting, she compliments him. “You’re a perfect example, Gary, of somebody that does want to turn their life around,” she assures him. After today, she tells Brown, when she shows their film in prisons, she can update prisoners on his new life. “They’re gonna be real excited to know that I saw you today,” she tells him. “Good,” Brown responds, amid a fresh torrent of tears. He continues: “You not only saw him, but we ate at the same table together, and we was able to laugh and talk and, you know, say good things. And we both have peace inside.”

During much of the encounter, White keeps her emotions in check, staying locked in on Brown and his needs. She learned shortly before this meeting that she needs a lung transplant, but she makes no mention of that to Brown. She’s here to make him feel better and is wary of saying anything that might set him back.

Then she asks Brown an innocuous question: Does he have his own copy of the film Meeting With a Killer? “I did,” he responds. And that leads to the story of Brown’s first adult relationship with a woman.

They met at his church. She was pregnant and needed a place to live. “At that time,” Brown tells White, “I was praying to God he’d help me find a lady who could accept me for everything I’ve done.” She moved in with him. He attended the birth of her baby girl. “Everything was clicking together,” Brown says. But then, “She started fallin’ back on her old ways.”*

He broke up with her but let her remain at the apartment until she found a new place. In the meantime, she was arrested on drug charges, and police raided their apartment while Brown was away. No drugs were found, and Brown passed a drug test. But he was convinced he would soon be sent back to prison. He made a panicky phone call to Halbert, the mediator in Brown’s 2001 prison meeting with White.

Brown told Halbert—who confirms his account—that his greatest fear was what his failure would mean to White and her family. He begged Halbert to assure White that “I didn’t let you down on the promise that I gave to you,” to live a better life. By now in the story, White is weeping for the first time today. “I would have believed it,” she tells Brown. “I would have believed it.”

“Every day that I’m out here,” he continues, “that was one more day I was telling you I was sorry for what I done. I would show you through my actions and my proof and what I do out here that shows you I wasn’t that kind of person of what I was back then. I was so worried about hurting you.”

“That’s incredible,” White says, laughing through her tears.

“Yeah. At the end I was thinkin’ about y’all. Wasn’t thinkin’ about me no more. I was thinkin’ about y’all. Cause y’all believed in me. Y’all gave me strength,” Brown says.

“I do believe in you,” White says.

* * *

In the past, I’ve wondered what White means when she says she has a relationship with Brown. Clearly she lives by her faith in forgiveness, second chances, and restorative dialogue, the message she has spread in the years since her first meeting with Brown. It’s also clear that she cares about Brown’s success outside of prison. But her ambivalence about seeing him after his release and her reluctance to discuss her and her family’s pain kept Brown at a safe distance. When these two first met 13 years earlier, they both emerged from the conversation transformed. Today, though, White seemed intent on only granting that gift to Brown, not to herself.

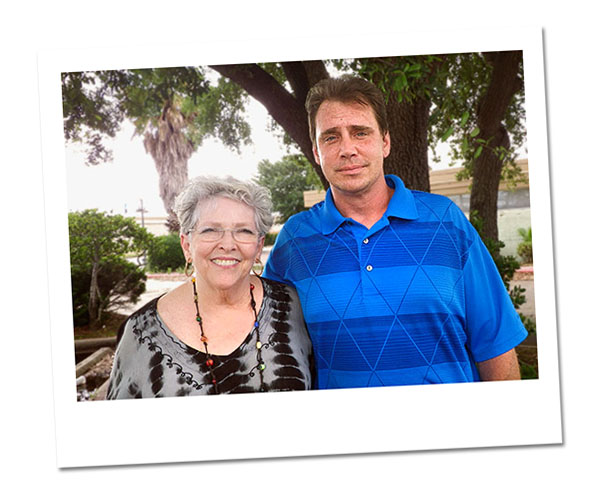

Linda White and Gary Brown after meeting on June 1, 2014, in Beaumont, Texas. Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo by Mark Obbie.

Now, with a fresh glimpse of Brown’s concern for her, White seems to be experiencing something like she did in the film: She is raw and open, reacting unexpectedly, and, perhaps, healing.

White wipes away her tears, shaking her head. “I mean, you are the real deal, Gary. You are the real deal.”

In early September of last year, Brown was jailed on an alleged parole violation. After one month in the county jail, during which the state held his parole revocation hearing, he was ordered to spend three more months in an intermediate sanctions facility—in essence, a re-education camp to help him see the error of his ways. “It’s kinda like a prison, but it’s not prison,” Brown explained.

Brown says it all started when he was seen texting during his weekly group counseling meeting. He said he wasn’t allowed back in the group until he worked it out with his parole officer. That took some weeks, and so he got cited for not attending group: a perfect Catch-22.

Brown begged me not to write about him, at least while he was still locked up, out of fear of further antagonizing the authorities. He said he understood why the state wanted to emphasize the importance of his group counseling and that he was learning useful lessons in the mandated sessions. “It could’ve been worse,” he said. He wasn’t sent back to prison, and he managed to keep his job. When he got out, he would still have an apartment, a truck, and employment.

Brown ignored my request for copies of the parole charges as verification, but whatever landed Brown in trouble, White believes it was innocuous. She’s seen the arbitrary heavy-handedness of the state at its worst. “It’s beyond stupid,” she says.

Finally, after four months away, Brown returned home. Since his release, White has kept loose watch over him but hasn’t tried to see him again. She’s been busy volunteering in prison—she was particularly excited about a guest appearance at California’s San Quentin State Prison—and distracted by her health concerns, though recently the news from her doctors has improved. Now 74, White is off the transplant waiting list for the time being.

Brown eventually stopped responding to my messages. In our last phone conversation, while he was still locked up, he told me, “I just want to get back out there and finish doing what I started.”

What he started is the law-abiding life his victim wants him to live now, the life she considers payment in full for the debt he owes her. Brown’s original sentence would have run until 2040, when he is almost 70. Until then, he’s a parolee, and the state of Texas is the final arbiter of what he owes society.

*Correction, July 6, 2015: This article originally misidentified the baby as a boy. (Return.)

This is the first in a series of articles on the victims of crime and the ways in which we fail them by focusing criminal justice on harsh punishment alone. Sign up for alerts about future installments below.