Where Yinz At

Why Pennsylvania is the most linguistically rich state in the country.

Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo

This month, Slate is republishing some of our favorite stories. Here’s today’s selection: Matthew J.X. Malady’s Good Word columns were a delight for dedicated linguists and word dabblers alike. This one from 2014 shed light on the verbal complexities and fascinations of Pennsylvania. Plus, Natalie Matthews-Ramo’s delightful illustrations will have you speaking like a Keystone State native in no time. —Abby McIntyre

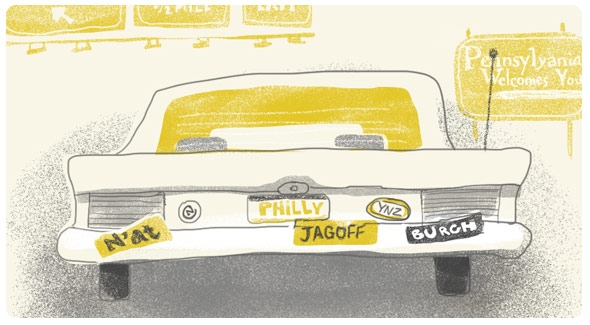

The 4 hour and 46 minute drive from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh is marked by several things: barns, oddly timed roadwork projects, four tunnels that lend themselves to breath-holding competitions, turnpike rest stops featuring heat-lamped Sbarro slices and overly goopy Cinnabon. But perhaps the most noteworthy—and useful—hallmark of that road trip is all the bumper stickers that one spies along the way.

From Center City Philly to about Reamstown, it’s all Eagles and Phillies and Flyers stickers. Then there’s a 150-mile stretch of road where anything goes. Penn State paraphernalia, Jesus fish, and stickers about deer hunting mix with every other form of car commentary to create a hodgepodge that predominates until about Bedford. From there, it really is all Steelers stuff. And for those who make this drive fairly often, that bumper sticker progression serves as an old-school GPS. Of course, you’ll also spot stickers referencing cheesesteak lingo, as well as those emblazoned with “N’AT,” on this trip. And if you’re from out of state and decide to rest-stop query the owner of a car bearing one of those stickers, within the first few words of that person’s spoken response you’ll realize why linguists love the Keystone State.

Pennsylvania, in case yinz didn’t know, is a regional dialect hotbed nonpareil. A typical state maintains two or three distinct, comprehensive dialects within its borders. Pennsylvania boasts five, each consisting of unique pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar elements. Of course, three of the five kind of get the shaft—sorry Erie, and no offense, Pennsylvania Dutch Country—because by far the most widely recognized Pennsylvania regional dialects are those associated with Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

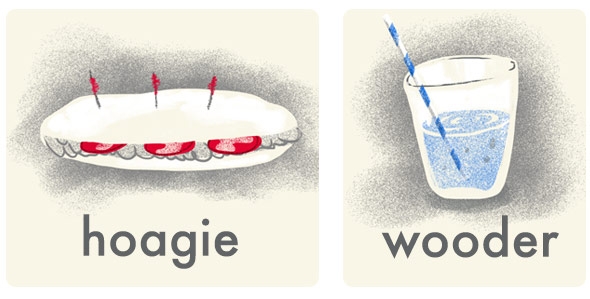

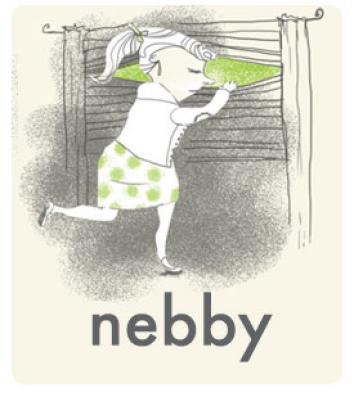

The Philadelphia dialect features a focused avoidance of the “th” sound, the swallowing of the L in lots of words, and wooder instead of water, among a zillion other things. In Pittsburgh, it’s dahntahn for downtown, and words like nebby and jagoff and yinz. But, really, attempting to describe zany regional dialects using written words is a fool’s errand. To get some sense of how Philadelphians talk, check out this crash course clip created by Sean Monahan, who was raised in Bucks County speaking with a heavy Philly accent. Then hit the “click below” buttons on the website for these Yappin’ Yinzers dolls to get the Pittsburgh side of things, and watch this Kroll Show clip to experience a Pennsylvania dialect duel.

Get More: Comedy Central,Funny Videos,Funny TV Shows

According to Barbara Johnstone, a professor of English and linguistics at Carnegie Mellon University, migration patterns and geography deserve much of the credit (or blame) for the variety of speech quirks on display in Pennsylvania. A horizontal dialect boundary that roughly traces Interstate 80 spans the length of the state. The speech and vocabulary of those living north of that line of demarcation, she says, were influenced by those who migrated into the U.S. through Boston mainly from the south of England. “Whereas the people in the rest of Pennsylvania below that tended to come to the U.S. from Northern England and arrived in Philadelphia and other places along the Delaware Valley,” Johnstone says. “They came from Northern England and Scotland and Northern Ireland.”

Those living north of I-80 have historically used different words for certain things than those living in the southern half of Pennsylvania—pail vs. bucket, for instance. And the pronunciation of various vowel sounds north of the boundary doesn’t align with how those vowels are pronounced in other parts of the state. “Rot can sound, to south-of-I-80 ears, like rat,” she adds, “or bus, like boss.”

Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo

Settlement in western Pennsylvania began to pick up around the time of the American Revolution, and those who set down roots in the area—predominantly Scotch-Irish families, followed by immigrants from Poland and other parts of Europe—tended to stay put as a result of the Allegheny Mountains, which bisect the state diagonally from northeast to southwest. “The Pittsburgh area was sort of isolated,” says Johnstone. “It was very hard to get back and forth across the mountains. There’s always been a sense that Pittsburgh was kind of a place unto itself—not really southern, not really Midwestern, not really part of Pennsylvania. People just didn’t move very much.”

The result was a scenario in which—with some exceptions, such as the transfer of the word hoagie from Philly to Pittsburgh—the two dialects could develop and grow independently. Fast-forward 250 years or so, and people from Pittsburgh are talking about “gettin’ off the caach and gone dahntawn on the trawly to see the fahrworks for the Fourth a July hawliday n’at,” while Philadelphia folks provide linguistic gems like the one Monahan offered up as the most Philly sentence possible: “Yo Antny, when you’re done your glass of wooder, wanna get a hoagie on Thirdyfish Street awn da way over to Moik’s for de Iggles game?”

He deciphered the easy elements—like “Antny” (Anthony), “hoagie” (submarine sandwich), “Iggles” (the Philadelphia Eagles)—before transitioning to the more upper-level material. “We have this very unusual grammar quirk with the word done,” Monahan explains. “When you say ‘I’m done’ something, it means the task is done. The rest of the country would say ‘I’m done with my water.’ But if I say ‘I’m done with my water’ in Philadelphia, that would mean I’ve had some, and I don’t want to finish the rest. If I say ‘I’m done my water,’ that means I’ve drunk all of it. They mean two different things.”

Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo

That’s not really the case anywhere else in the country. There also aren’t many places, he adds, where people refer to someone named Mike as “Moik” in conversation. “That ‘oi’ is what I would call the defining Philadelphia sound in the way that the Philly accent is today,” Monahan says. As for “Thirdyfish Street”? That’s “Thirty-fifth Street” to you and me. Philadelphians often replace “th”s in words with other sounds, though, and “everything just winds up getting all blurred together.”

According to University of Pennsylvania linguistics professor William Labov, the Philly dialect represents a tug of war between the city’s connections to, and influences from, different parts of the country. “I think Philadelphia is torn between its northern and southern heritage,” he says. The result is a regional dialect that combines many influences to form a one-of-a-kind manner of speaking. And, he adds, it’s a way of speaking that has become a source of pride for many residents. Labov is currently working on a project at Penn that involves interviewing students who have graduated from Philadelphia high schools to determine their perceptions about Philly. “Most are very positive about the city and see themselves staying in Philadelphia,” he says. “As far as the dialect is concerned, only a few points have become self-conscious. For most of Philadelphia, the general attitude is quite positive.”

Across the state, in western Pennsylvania, Pittsburghese has developed over time into a badge of honor for locals—something akin to a spoken symbol of blue-collar toughness and tradition. Notoriety on the dialect front gained steam when linguists began visiting the area in the 1930s and ’40s, providing scholarly support for the notion that Pittsburghers had developed a unique way of talking. Around the same time, Johnstone says, interactions between those from Pittsburgh and people from other parts of the country during World War II resulted in a more broad recognition of the phenomenon. Things really picked up during the 1960s, as more linguists focused on the region and newspapers began running pieces on elements of the dialect. The publication of Sam McCool’s New Pittsburghese: How to Speak Like a Pittsburgher in the 1980s represented the first time that someone had detailed for a mass audience the sounds and words that make up the dialect, and it provided thousands of displaced Pittsburghers a way to reconnect with their home town. (Many of them moved to other states when the local economy tanked.) The widespread use of personal computers during the years that followed meant that people all over the world could discuss Pittsburghese at any time, and the topic now garners more attention than ever.

But as the national and international buzz about the distinctiveness of both accents increased, so did the number of young people from the state’s two largest cities who decided to attend college far away from home. As familiarity with various unique elements of Pennsylvania’s dialects reached an all-time high, the influence of those dialects on younger generations was challenged.

Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo

“You learn really fast when you first show up [to college], because, particularly if you’re a freshman, you’re an undergraduate, you’re the new kid on the block and you don’t want to stick out,” says American University linguistics professor Naomi Baron. “If you look at the history of broadcasting in this country, when broadcasting went national, one of the things that happened is there were handbooks written for national radio broadcasters on how to eliminate the regionalisms from their speech so that they would be understood across the country. And in a sense that’s what a lot of people do when they come to college today. They drop what they assume are going to be the regionalisms.”

Pittsburgh native and nj.com sportswriter Dom Cosentino is one of those who left the Steel City for an out-of-town college. That school, La Salle University, also just happened to be in Philly. It was a rude awakening. “I had no clue about any of it—that Pittsburgh people even talk a certain way—until I moved away,” he says. “Almost immediately I noticed I talked differently, and I noticed other people talked differently. They would kind of make fun of the way I talked, or the way I’d say certain words—I was calling my ‘mawm’ instead of my ‘mom,’ and that kind of thing.” In a very short period of time, Cosentino says, he went from being “Dawm” to “Dom.” “I wouldn’t say that I went to a full-on Philadelphia accent, but it wasn’t long before I was coming back to Pittsburgh and my friends were sort of making fun of the fact that I didn’t talk like I was from Pittsburgh much anymore.”

Baron sees that same scenario play out year after year on campus, with the net impact being thousands of dropped accents. Of course, some regional language quirks may return if and when students move back to their hometowns after college. But many won’t. So, extrapolating over the course of 20 or 50 or 100 years, does that mean the Philly and Pittsburgh dialects are destined to disappear? And will our contemporary propensity to communicate via text rather than speech speed that decline?

First, the good news: According to Baron, who is the author of Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World, all the time we spend emailing and texting and tweeting and IMing doesn’t portend the downfall of distinctive regional dialects. She has been teaching for a “number of years, including pre-personal computers and post, and before all the new technologies that have come in the last five to 10 years,” Baron says. “And what’s really clear to me is that the technologies aren’t having any influence at all on dialects.”

We may speak less to one another these days, but when we do speak, Baron says, we talk pretty much as we have in the past. And those conversations are now more likely to occur in environments that are welcoming of accents and strange names for things and unusual pronunciations. “As the world gets more internationalized in so many ways, we don’t notice things like accents the way we used to,” Baron says. “Day to day, we see so many people who speak so many versions of English. We don’t judge people nearly as much, and therefore people are free to speak the way they have spoken, including with regional accents and dialects.”

Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo

A March New York Times piece titled “The Sound of Philadelphia Fades Out” appears to serve as a wet blanket to Baron’s optimism about the persistence of regional dialects. The article cited a 2013 University of Pennsylvania study for the proposition that “the Philly sound is conforming more and more with the mainstream of Northern accents.”

But if you talk to William Labov, who co-authored the study, you’ll get a decidedly less fatalistic perspective on the trajectory of the dialect. He refers to analysis of sound and speech changes as “a game of musical chairs,” and suggests that making broad pronouncements based on shifts in one element of a dialect is probably not a good idea. “Philadelphia is maintaining its local dialect, and developing in new directions,” Labov notes. “I would say that the dialect is in pretty good shape.” Monahan agrees. He says the Times piece is too simplistic in its summation of the linguistics involved. “Certain vowels are getting less strong over time,” he notes, but “others are getting stronger.”

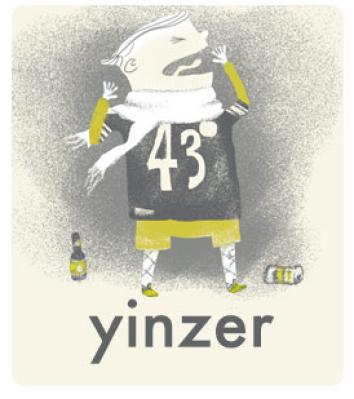

Johnstone is quick to point out that the Pittsburgh dialect—and how people perceive it—is constantly evolving. She notes the increased national attention garnered by the word jagoff during the past few years (“If you’re an outsider, you don’t know whether or not it’s obscene”), and the development of the “yinzer” persona as a common stereotype. “It seems to be getting used for a particular kind of working class person—male or female, but usually male—who is kind of loudmouthed and maybe not quite so smart and has all the stereotypical characteristics of Pittsburgh: has never moved away from home, loves the Steelers, loves to party, likes to drink beer,” says Johnstone, adding that widespread use of the term only really began around 2000. “It’s both negative and positive. It’s both mocking and also something that people orient to.”

Twenty years from now, though, yinzer might be used to describe someone who has moved away from Pittsburgh, and by 2040 “Thirdyfish Street” may have morphed into “Thirfistree.” This year’s jagoff may be next year’s gutcheez. Or, as Johnstone notes, all those words could fall out of use altogether. The history of language tells us that almost nothing remains static or lasts forever. “It’s a fact about language. This process has been going on forever. What happens is that there are new ways of speaking that develop.”

And, according to Labov, those new ways of speaking will give us new things to fixate on and gab about. As we grow familiar with certain publicized hallmarks of a given dialect, those elements tend to dissipate, only to be replaced by other unique language strains that often show some connection to what came before. “When people become aware of particular sounds, it’s like throwing a monkey wrench into a car,” Labov says. “It’s going to bang up part of it, but the rest of it will go on its own way. And the car runs.”