All Ours

Do couples do best when they pool all their money, old-fashioned as it may seem?

This series is now available as an eBook for your Kindle. Download it today.

Whenever my husband, Mike, and I talk about merging all our money, I flash to the purchases I don't want him to know about. For instance: I don't want him to know I blew $400 on a Rachel Comey blouse to wear to his birthday party. I imagine what he would say if he saw the receipt. "Is it made of gold?" or "I like you just as much in a T-shirt." I can justify the expense to myself. I can afford occasional fripperies; it's important to me to feel attractive at big events. But that's me, not him. As for his habits, do I really want to know how much he spends on DVDs, when most of them are sitting in the corner of our living room, still in their plastic wrapping? The question recalls for me Elizabeth Weil's quip in the New York Times Magazine about her foodie husband's predilection for purchasing haute staples like Blue Bottle coffee at $18 a pound: "We spent far more money on food than we did on our mortgage."

In our quest for a system of financial management, my fear that Mike and I will judge each other is one of my hang-ups about the Common Pot method, my name for putting all our money in joint accounts. Another worry is that I'd lose some fundamental, hard-won autonomy.

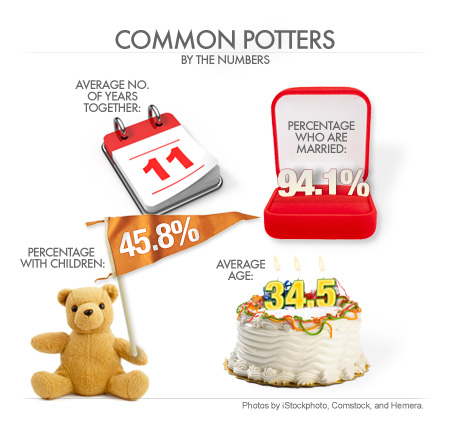

Later this week, I'll explore what I call the Sometime Sharer method for couple finance, a combination of joint and individual accounts; and the Independent Operator system, which entails strict financial separation. Today, I'm focusing on the Common Pot, and what I have to report comes largely as a happy surprise for me. The Common Potters I spoke to, drawn from the survey I posted on Slate last fall, were largely accepting of each others' spending habits. And rather than feeling confined by old-fashioned mores, many couples said that sharing all their resources is a tangible demonstration of their bond to each other. At the same time, my reporting didn't assuage all my concerns that this method stifles individual freedom—particularly for women.

I'll start with Tamara, 28, a lawyer, and her husband Peter, 27, a paralegal. (I've changed their names at their request.) Tamara and Peter met as trumpet players in their high-school marching band, which means they've been together since before they had driver's licenses. They started pooling their money when they moved in together during college. They continue to pool all their earnings and savings, and though at the moment Tamara makes nearly four times what Peter does, she does not begrudge any of his spending. "I can't see myself getting mad at him for splurging on a little something," she says. This is Peter's last month at his job: He just quit so he can figure out his true calling, and Tamara says her attitude toward his spending will not change even when he's not bringing in a salary. "All money is our money," she explains. When she was in law school, Peter supported her—now it's his turn.

And yet, some of Tamara's friends from law school are not so comfortable with her financial arrangement. They tell Tamara she's a "fool" for becoming the sole breadwinner and make comments like, "I couldn't be with anybody who didn't work as hard as I do." The peanut gallery didn't say a word when Peter was working and Tamara was in school. So why does the couple's Common Pot bother them now?

Perhaps Tamara's friends got messages like the one I got from my grandmother—women should have their own money—and, like me, they hadn't thought through the way advice like this actually applies to their modern lives. My grandmother had a Common Pot by default, not by choice, because she never earned her own money. If she and my grandfather had divorced, she would have been in major financial trouble. She was living the norm for the time: Only 32 percent of wives in 1960 were in the labor force (PDF). Even though circumstances are different now, many women have internalized the message. Like Jill, 29, who wrote to tell me that her mother was left with nothing when her parents split and drilled into her, "Keep some money separate so if the 'spit' hits the fan you'll have a little something to fall back on."

Does this advice still make sense, now that 61 percent of wives work, and divorce law in most states provides for equal or equitable distribution of assets? For me, the answer is, not really. Talking to Common Potters like Tamara and Peter made me see something I'd missed before: There is a difference between earning your money and keeping your money, and the former is what is actually important to me. In my marriage, I feel like I'd have decision-making power over any shared pot, which my grandmother did not. And if something happened to Mike, or to our relationship, I would not feel helpless or screwed over. I would be able to support myself, as I always have.

What about women who don't work—does a Common Pot come with a bigger downside for them? That's a harder question for me to answer. On the one hand, it's no longer really socially acceptable for a husband to tell his wife she has no say over the way they spend money as a couple, the way it was acceptable for my grandfather to be the sole financial decision-maker. On the other hand, some women who don't work are unsettled about their traditional role. For every stay-at-home mom like Holly, 35, who says of her husband, "I'm thrilled he is able to provide for us," there is a stay-at-home mom like Rachel, 38, who wrote to me, "In general I've had negative feelings about my own lack of career and my work outside the home."

Stay-at-home moms aren't the only ones who are ambivalent about having a Common Pot. If you and your mate have divergent spending styles, this method can be a disaster. Take Beth, 40, an attorney, and her husband Alan, 39, who works for a cable company. (I've changed their names, too, for privacy's sake.) Alan keeps track of every penny they both spend with Quicken. Beth most definitely does not. "Every time I go to Target, he'll want to know what was that $100 spent on. Greeting cards? I don't know!" She appreciates that he is so diligent about their money, but she also feels like he doesn't trust her, even though she managed her own finances without going into debt for 10 years before they were married. "He thinks I would go crazy and drive us into the ground if he didn't know where every dollar was going," she says.

Beth says she feels micromanaged. And certainly, there are men out there who still use money as a way to control their wives—I got one heartfelt e-mail from a woman who said she would never share money with a man again because her abusive first husband froze their joint account when she tried to leave him. However, Tamara's friends don't have this worry about Peter: Instead, they think he'll be a mooch. Where does that assumption come from?

A recent survey from Pew (PDF) showed that 40 years after the women's liberation movement, Americans are still uncomfortable with the idea of a woman as the breadwinner. We're onboard with women working: According to the survey, 62 percent of men and women say the ideal marriage is one in which both husband and wife work and take care of the children. But beneath the surface, we're not quite ready for women's contributions to their families to be on equal footing with men's. When Pew asked about whether it was important for a woman to be able to support a family in order to be ready for marriage, only 33 percent said yes. When Pew asked the same question about men, 67 percent said a man should be able to support his wife before he gets hitched. Tamara's friends may reflect the widespread American belief that real men take care of their families.

There's a class wrinkle, here, though: People who make less money than high earners like Tamara's law school chums are more likely to say that it is important for women to be good providers : 44 percent of people who earned less than $30,000 a year believe that women should support their families vs. 28 percent who earned more than $75,000 a year, according to the Pew survey. Perhaps this is because, historically, low-income women have long had to work to support their families, while middle- and upper-middle-class women have been working outside the home in large numbers only for the past few decades. Or perhaps it's because wealthier women are less ready to upend old-fashioned ideas about masculinity. From the point of view of equity, it's discouraging that upper-income women aren't more supportive of arrangements like Tamara and Peter's. A Common Pot like theirs, and the two-way trust it's founded on, allows women to go for glass-ceiling-breaking gigs with a spouse who is in a position to take the lead on child care, when the babies appear.

For couples with big income disparities, the Common Pot also can pave over the uneasiness that either spouse may feel about their uneven finances. If all the money coming into a relationship goes into a single set of accounts, no one has to constantly revisit what proportion is his or hers, and couples don't have to keep discussing who is paying for what. This can be true whether it's the man or the woman who earns more. A 27-year-old with a doctorate wrote to me about how her Common Pot makes it a nonissue that her husband now earns three times more than she does. "I don't feel like we fight about that disparity at all—the money all feels like 'ours,' " she says.

Because Mike and I were wary of combining any money before we were married, we still think of the money we earn as "yours" and "mine." But from the couples I interviewed, I heard over and over again about the psychological importance of "ours." Most Common Potters I spoke to believe that shared money is an inextricable part of a true union, with easing the awkwardness of income disparity as a side benefit. Brian, a 31-year-old in marketing and communications, offers this quote from Wendell Berry to explain his reasoning for the Common Pot he shares with wife Keri, 30, who is a stay-at-home mom:

There are, however, still some married couples who understand themselves as belonging to their marriage, to each other, and to their children. … To them, 'mine' is not so powerful or necessary a pronoun as 'ours.'

The How-To Part: Managing Common Pot Accounts

Though Tamara is the main breadwinner, it is Peter who does more of the work of managing the couple's Common Pot. Once a month, Peter uses a simple spreadsheet to run the numbers for the couple's regular expenses. He divides the money that he and Tamara earn monthly into 13 categories, using a column for each category: rent, electricity, landline/Internet, cell phones, transportation/fuel, entertainment, emergency fund, student loans, credit card, savings, IRAs, Peter's spending money, and Tamara's spending money (click here to see the couple's spreadsheet). The credit card is used for miscellaneous expenses such as groceries and clothing. After checking with Tamara, Peter pays the bills from the couple's checking account. They discuss and decide together on student-debt repayment and investment strategies.

Thirty-five years ago, women mostly managed the domestic budget, even though (or perhaps because) they then earned much less of it. In a 1975 Roper Organization poll, 58 percent of married women said they paid all or most of the monthly bills, compared with 47 percent of men. Several women I spoke to remembered their mothers sitting at the dining room table balancing the family's checkbook, sometimes with thick-framed glasses perched on their noses.

Now that earning is more equal between men and women, money management seems to be more evenly divided, too. In the responses to my survey, almost 50 percent of married women with a Common Pot said they mostly manage the money in their household, eight percentage points lower than the older Roper survey. Nearly 50 percent of married men with a Common Pot say they're the ones who are up late paying the bills. Almost 30 percent of married men and women said they managed the money together with their spouses.

The couples I talked to in which one person mostly managed the money said that he or she had better math skills or was more meticulous. In Tamara and Peter's case, Peter does the brunt of management because he has more free time. Sociologists call this "voluntary specialization." They key word here is voluntary: Both halves of the couple should be comfortable with one person taking the lead, or else it leads to strife.

Occasionally voluntary specialization can lead to couples relying on some old-fashioned gender stereotypes. Sometimes when wives were the ones managing, my interviews with couples had Judd Apatow moments. As 27-year-old Ryan says about his wife, Anna (names changed for privacy), "The way that we present ourselves to friends and families, we're both adults, but she's the more responsible one, and I'm the sillier one."

The Common Pot works well for Tamara and Peter because they have the same attitude toward each other's spending. They even go shopping together for clothes, and Tamara can't understand why anyone would freak out over, say, a $400 Rachel Comey blouse. Though I was initially skeptical of the touchy-feely couples shouting "ours" from the rooftops, I was ultimately rather moved by Tamara's invocation of the word. Tamara and Peter's attitude toward money seemed healthy, and their bond solid and sweet. The Common Pot hasn't smothered their individuality—it has allowed Peter and Tamara to pursue their personal intellectual dreams. I do trust my husband not to spend money we don't have, and he trusts me, too. I can feel my resolve against merging my money with Mike's beginning to soften.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.