The Passion of Lew Wallace

The incredible story of how a disgraced Civil War general became one of the best-selling novelists in American history.

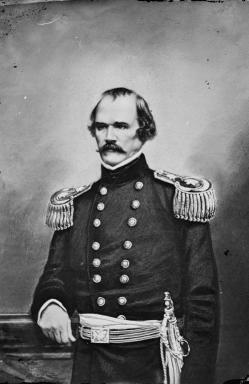

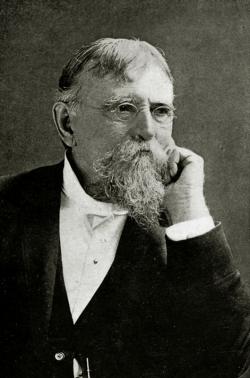

Courtesy of Brady-Handy Photograph Collection/Library of Congress

You can also listen to John Swansburg read this piece using the player below:

I.

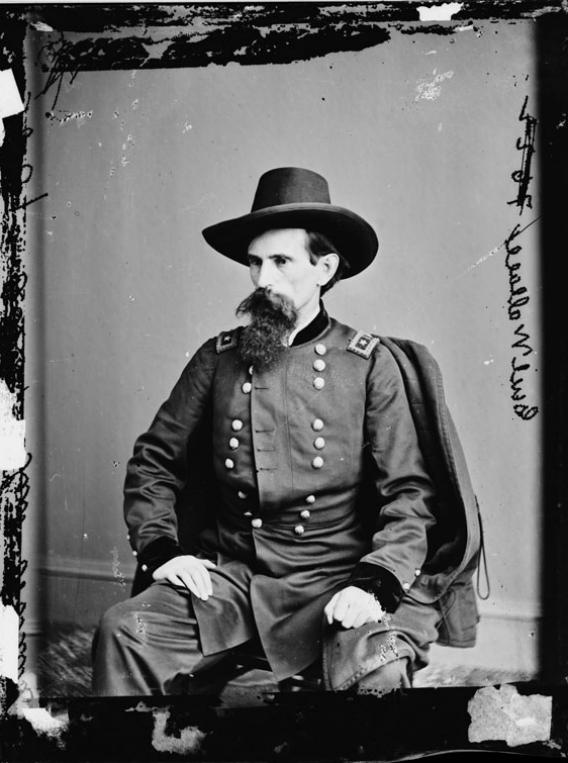

Lew Wallace was making conversation with the other gentlemen in his sleeper car when a man in a nightgown appeared in the doorway. The train was bound for Indianapolis and the Third National Soldiers Reunion, where thousands of Union Army veterans planned to rally, reminisce, and march in a parade the New York Times would later describe as “the grandest street display ever seen in the United States.” It was Sept. 19, 1876, more than a decade since the Civil War had ended. Wallace had grayed a bit, but still wore the sweeping imperial moustache he’d had at the Battle of Shiloh. “Is that you, General Wallace?” the man in the nightgown asked. “Won’t you come to my room? I want to talk.”

Robert Ingersoll, also a veteran of Shiloh, was now the nation’s most prominent atheist, a renowned orator who toured the country challenging religious orthodoxy and championing a healthy separation of church and state. Wallace recognized him from earlier that summer, when he’d heard Ingersoll, a fellow Republican, make a rousing speech at the party’s nominating convention. Wallace accepted his invitation and suggested they take up a subject near to Ingersoll’s heart: the existence of God.

Ingersoll talked until the train reached its destination. “He went over the whole question of the Bible, of the immortality of the soul, of the divinity of God, and of heaven and hell,” Wallace later recalled. “He vomited forth ideas and arguments like an intellectual volcano.” The arguments had a powerful effect on Wallace. Departing the train, he walked the pre-dawn streets of Indianapolis alone. In the past he had been indifferent to religion, but after his talk with Ingersoll his ignorance struck him as problematic, “a spot of deeper darkness in the darkness.” He resolved to devote himself to a study of theology, “if only for the gratification there might be in having convictions of one kind or another.”

But how to go about such a study? Wallace knew himself well enough to predict that a syllabus of sermons and Biblical commentaries would fail to hold his interest. He devised instead what he called “an incidental employment,” a task that would compel him to complete a thorough investigation of the eternal questions while entertaining his distractible mind. A few years earlier, he’d published a historical romance about the Spanish conquest of Mexico, to modest success. His idea now was to inquire after the divinity of Christ by writing a novel about him.

It took four years, but in 1880, Wallace finished his incidental employment. He called it Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. It’s one of the great if little known ironies in the history of American literature: Having set out to win another soul to the side of skepticism, Robert Ingersoll instead inspired a Biblical epic that would rival the actual Bible for influence and popularity in Gilded Age America—and a folk story that has been reborn, in one medium or another, in every generation since.

II.

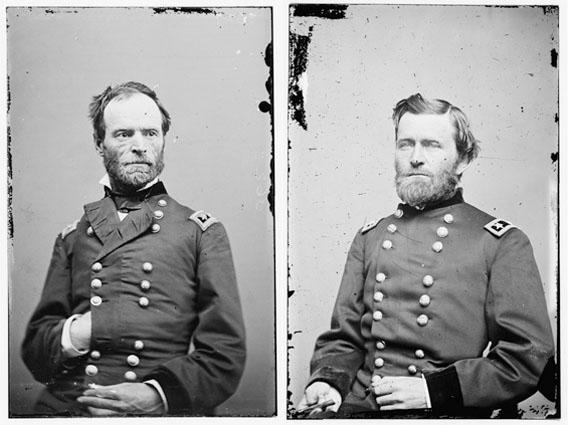

The ongoing celebration of the Civil War’s 150th anniversary has focused thus far on the conflict’s traditional heroes. Ulysses S. Grant is the subject of a best-selling biography; Abraham Lincoln just won an Oscar. Lew Wallace is not one of those heroes. He lacked Grant’s training and instincts for war, and possessed nothing akin to Lincoln’s political genius or personal charm. Wallace was brave but overconfident on the battlefield, impatient and impertinent off of it. The Union’s two greatest generals, Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, both rebounded from early missteps—Sherman was so spooked after the Union’s defeat at First Bull Run that critics openly questioned his sanity. Wallace, however, couldn’t live down his early stumble, at Shiloh, and spent much of the war on its sidelines.

Yet Wallace’s unlikely journey from disgraced general to celebrated author is as thrilling as any story of his era, and his fame in his own lifetime surpassed that of all but a handful of his comrades in arms. Few men participated so completely in the postbellum American experience. Wallace had a Zelig-like knack for insinuating himself into the defining moments of his day. A lawyer by training, he served on the tribunal that tried the Lincoln assassination conspirators and presided over the one that convicted Henry Wirz, the commandant of the notorious prison camp at Andersonville, Ga., and the only Confederate executed for war crimes. During the disputed election of 1876, the Republican Party sent Wallace to oversee the original Florida recount. For his role in delivering the White House to Rutherford B. Hayes, he was rewarded with the governorship of the New Mexico territory. The duties of office included putting down a range war in Lincoln County; among the combatants was William H. Bonney, better known as Billy the Kid. Initially charmed by the young gunslinger, Wallace once asked him for a demonstration of his marksmanship and was impressed by his handling of both six-shooter and rifle. He soon tired of the Kid’s homicidal antics, however, and put a $500 bounty on his head.

His role in the life and death of Billy the Kid earned Wallace a bit part in the dime novels that burnished the outlaw’s legend, but it was nothing compared to the celebrity his own novel brought him. He had begun the book in his native Indiana, writing in the shade of what would come to be known as the Ben-Hur beech, and would finish it in Santa Fe. At night, after he’d wound down the territory’s affairs, he would retreat to a dismal back room of the adobe governor's palace and bar the doors and windows. Sitting at a rough pine table, he composed the novel’s eighth and final book by the light of a solitary lamp.

Wallace’s novel has since been eclipsed in the American imagination by a bronzed, bare-chested Charlton Heston, careening around the Holy Land in William Wyler's 1959 film adaptation of Ben-Hur, which won a record 11 Academy Awards and was a blockbuster hit for MGM. But the book was wildly popular in its day, selling perhaps as many as a million copies in its first three decades in print. The story of the Jewish hero Judah Ben-Hur, whose life Wallace ingeniously intertwined with that of Jesus Christ, captivated readers despite winning little affection from contemporary critics, who found its romanticism passé and its action pulpy. On a visit to Boston, home of the literary old guard, Wallace noted with pique that William Dean Howells, James Russell Lowell, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. all declined invitations to parties held in his honor. “Why did they not come?” he wrote to his wife Susan. “Would their presence have been too much of a sanction or endorsement for the wild westerner?”

Ben-Hur found admirers in other high places. Grant, who hadn't picked up a novel in a decade, read Ben-Hur in a single, 30-hour sitting. President James A. Garfield, a former professor of literature, devoured it nearly as fast, stealing chapters between meetings. He woke at 5:30 one morning so he could finish it in bed. "With this beautiful and reverent book you have lightened the burden of my daily life,” he wrote to Wallace later that same day. Ben-Hur’s publisher, Harper & Brothers, soon produced a Garfield Edition, with the president’s letter reproduced as a foreword; the lavishly illustrated two-volume set sold for a then astronomical $30.

The novel’s readership wasn’t confined to Union veterans. In an Indiana newspaper, the historian S. Chandler Lighty discovered Varina Davis’ account of reading Ben-Hur aloud to her father “from 10 o’clock until daybreak, both of us oblivious to the flight of time.” Her father was Jefferson Davis, the former Confederate president. Men and women on both sides of the Mason-Dixon could enjoy Wallace’s tale of martial virtue set safely in the distant past and embrace its message of Christly compassion triumphing over Old Testament vengeance. The story of Ben-Hur’s success is, in part, the story of how Americans put the divisions of the war behind them in the waning days of Reconstruction.

It’s also the story of how they welcomed a new era of economic opportunity. Among other things, Ben-Hur is a rags-to-riches story, in the mode of Wallace’s contemporary, Horatio Alger. Judah’s virtuousness is tested, and richly rewarded, throughout the novel. The Gospel of Matthew teaches that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. In Ben-Hur, Wallace suggests that piety brings with it prosperity—an alluring prospect to readers eager to take part in Gilded Age affluence.

Wallace himself had struggled financially through much of his life. His correspondence is full of enthusiastic accounts of railroad investments and mining prospects that never pan out; he patented unprofitable improvements to railway ties, automatic fans, and the fishing rod. But Ben-Hur opened the doors of opportunity. The novel so impressed President Garfield that he offered Wallace the position of minister plenipotentiary to the Ottoman Empire (annual salary: a princely $7,500) and encouraged him, when not attending to U.S. interests, to gather material for a new novel. By the time Wallace returned from Constantinople four years later, Ben-Hur had become Harper & Brothers’ top-selling title. A steady stream of royalty checks freed Wallace from the practice of law (“that most detestable of occupations,” he called it) and from his creditors. “I contemplate with great satisfaction the pains that will wrench his little pigeon heart when he hears that all my debts are paid,” Wallace wrote of one of them, his brother-in-law.

Courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, M0292

Wallace enjoyed his newfound wealth. He built the finest luxury apartment building in Indianapolis—the Blacherne, named for an imperial palace in Constantinople—and kept a grand apartment for himself. Next to his home in nearby Crawfordsville he erected an idiosyncratic study—Ben-Hur’s face peers out from a frieze above the entrance—where he could pursue his avocations. He played the violin and made his instruments by hand. He was also an accomplished visual artist. During the Lincoln conspiracy trial, Wallace passed the time making sketches of the accused, which he later used as the basis for a large oil painting. Having grown up in the woods of the Old Northwest, he was an avid outdoorsman, and spent much of his leisure time hunting and fishing at his newly acquired game preserve, Water Babble.

Yet for all the worldly comfort Ben-Hur brought its author, Wallace was restless. He wasn’t just a writer of romances; he was a romantic himself, with a chivalric sense of honor, and he was plagued by the blot left on his reputation by the Battle of Shiloh. That battle, in which 26,000 men were killed or wounded, scarred all of its participants. Robert Ingersoll, then a Union cavalryman, spent the first day corralling infantry as they fled the slaughter of the front lines; when a storm broke that evening, he wrote that the rain fell "slowly and sadly, as though the heavens were weeping for the dead." Even the usually imperturbable Grant was taken aback. Writing of Shiloh in his memoirs, he recalled a field “so covered with dead that it would have been possible to walk across the clearing, in any direction, stepping on dead bodies, without a foot touching the ground.” Shiloh wouldn’t be the bloodiest fight of the war, but it was the first to intimate the horrors to come, and it dispelled any hope of a quick end to hostilities. After Shiloh, Grant wrote, “I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest.”

It’s difficult to comprehend death on this scale; now try to imagine being blamed for it. On April 5, 1862, Lew Wallace had been the youngest major general in the Union Army, a promising if brash officer who’d fought ably during the early months of the conflict. But on April 6, when the Confederates attacked and nearly succeeded in overrunning Grant’s Army of the Tennessee, Wallace failed to bring his sorely needed troops to the field of battle, and he shouldered a heavy portion of the blame for the dire toll. He was rumored to have gotten lost on the short journey to Shiloh’s front lines—or worse, to have lost his nerve. Within a few months, he was relieved of his field command. He spent the rest of the war trying to win back the confidence of his superiors and the rest of his life trying to prove his innocence. In Ben-Hur, Wallace had written a novel that would help America forget the Civil War. But its author never could.

III.

One of Lew Wallace’s earliest memories was of hiding amid a hillside stand of ironweed and watching his father drill the local militia of Covington, Ind. The Sauk leader Black Hawk was doing battle with settlers in neighboring Illinois—where a young Abraham Lincoln had volunteered for service—but his campaign to win back his people’s land would soon be defeated, to the relief of Covington’s home guard. Though David Wallace was a West Point graduate, most of his men carried umbrellas and cornstalks in lieu of muskets during their training exercises. To his 5-year-old son, however, “nothing of military circumstances half so splendid and inspiring had ever taken place.”

The Wallaces were a prominent if not a wealthy family. David, a lawyer, would eventually serve a term as Indiana’s governor and move his family to the state capital. But Lew spent much of his boyhood in the country, on what was then still the American frontier. In his posthumously published autobiography, he describes a boy who would have been at home in Tom Sawyer’s gang, forever fleeing instructors and marching off to do imaginary battle with a sword made of old clapboards. In 1842, when Wallace learned of Texas’ War of Independence, he and a friend provisioned a canoe and set out down the White River to offer their services to James Bowie and Davy Crockett. Lew’s grandfather apprehended them a few miles downriver. Wallace was 15.

Courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, M0292

Though he disdained the schoolhouse, Wallace was from an early age an avid reader, consuming the works that would shape his literary sensibility and further whet his appetite for war. The romances of Sir Walter Scott and Jane Porter’s account of William Wallace’s heroism in the face of British oppression made him long for a chance to prove his own mettle. In the meantime, he would carry himself like a goodly knight. A neighbor described him as having “the bearing of a soldier and the manners of a courtier.” That courtly manner, and his striking good looks—tall, sinewy, with “a dark and beautiful face, correct in every line,” in the words of one admirer—would help him win the hand of Susan Elston, who married Wallace despite her father’s dim view of his prospects and memories of prior offences. As a boy, Wallace had snuck into the stately Elston home to behold two domestic items unfamiliar to him: a sofa and a piano.

With reluctance, Wallace followed his father into the legal profession, and he was preparing for the bar exam when the United States declared war with Mexico in 1846. The 19-year-old tried to complete his studies, but his mind was already in Matamoros. “Of what consequence was a license to practice law?” he wrote. “How petty the soul which could be screwed down to prefer a court to a camp!” In his autobiography, which unlike his fiction admits a touch of humor, he recalled appending a note to his hastily completed bar exam:

“Dear Sir,—I hope the foregoing answers will be to your satisfaction more than they are to mine; whether or not, I shall go to Mexico.”

A few days later, the examining judge replied:

“Dear Sir,—The court interposes no objection to your going to Mexico.”

“The communication was unaccompanied by a license,” Wallace wrote. He volunteered his services to the U.S. Army.

Wallace imagined the conquest of Mexico would be full of the “gallantries” he’d read about in novels. Instead, his regiment was ordered to garrison an unnamed camp at the mouth of the Rio Grande, across the river from a small Mexican smuggler’s outpost, which the soldiers called “Bagdad.” The camp was soon beset with an epidemic of diarrhea so fatal that the survivors ran out of wood for coffins. The men heard of Gen. Zachary Taylor’s victories from passing steamboats. But if Mexico failed to live up to Wallace’s romantic notions of war, it also failed to disabuse him of them.

IV.

When he returned from Mexico, Wallace hung a black-and-white shingle outside a small office in Covington advertising his services as a lawyer. Though he’d finally acquired a license to practice, business was not brisk. One day, Wallace accompanied a colleague to a tavern in nearby Danville, Ill. There the young lawyers met a man Wallace described as “the gauntest, quaintest, and most positively ugly man who had ever attracted me enough to call for study.” The man was engaged in a storytelling contest with several local lawyers, and, despite his rough aspect, was running away with the competition, exhausting all comers with a seemingly endless store of well-spun yarns. It was Wallace’s first glimpse of Abraham Lincoln.

By the time Lincoln was inaugurated in 1861, Wallace’s fortunes had improved slightly. He had worked as a prosecutor, won election to the state Senate, and defected from the Democratic Party to the Republican, more out of a commitment to the Union, and a growing admiration for Lincoln, than any ardent abolitionist feeling. When Fort Sumter came under fire in April, Indiana’s Republican governor, Oliver P. Morton, called on Wallace to help him organize Indiana’s volunteers, a duty Wallace accepted on the condition that he might command one of the state’s six regiments once they’d been mustered. Morton agreed, and Wallace was commissioned a colonel. He was about to get his second taste of war, and his first chance to realize his dream of winning honor in the line of duty.

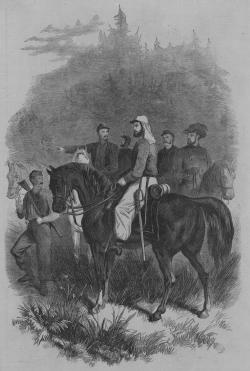

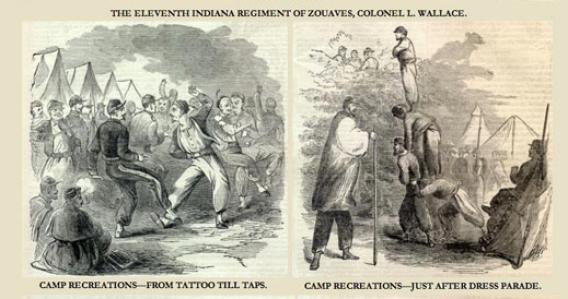

In a full-page illustration by Winslow Homer, published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly in 1861, Wallace sits astride his horse in a pair of billowing trousers, an exotic-looking kepi perched on his head. He is wearing the uniform of the Zouave, elite units of the French Army that borrowed their tactics and uniform style from Algerian fighters. Zouaves moved swiftly, reloaded their weapons on the ground (as opposed to making a target of themselves standing up), and communicated by bugle calls rather than verbal orders, which could be drowned out in the din of war. According to Robert and Katharine Morsberger, Wallace’s most comprehensive biographers, he first encountered the Zouaves in a magazine article. The modified tactics must have pleased Wallace the tinkerer; the uniforms surely satisfied his taste for pageantry. When he’d taken command of the 11th Indiana volunteers, he’d resolved to train and outfit his men in the manner of the Zouave.

Courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, P0455

In June, before the war’s first major battle was fought at Bull Run, Wallace’s regiment was ordered to Cumberland, Md. to support Union activities in the vicinity of Harper’s Ferry, then in rebel hands. Alerted to the presence of a Confederate garrison in a nearby town, Wallace decided to put his Zouaves into action. After a 20-mile march under cover of darkness, the 11th Indiana surprised a small unit of Confederates holed up in the town of Romney, in what is now West Virginia. The regiment’s unfamiliar tactics “frightened the rebels and they all took to their heels like scared cats,” as one of Wallace’s men put it in a letter cited by Gail Stephens, a student of Wallace’s military career. The enemy withdrew after a brief skirmish, leaving behind their supplies and slaves. A Zouave who sustained minor injuries after being shot in the belt buckle represented the lone Union casualty.

The victory at Romney was of minor strategic value, but it was early evidence that the Union Army could hold its own against the vaunted rebels and, to Wallace, proof of his ability as a commander. A friend in Washington told Wallace that President Lincoln had spoken of his “splendid dash on Romney.” Harper’s Weekly sent an illustrator to make a series of drawings of the now famous 11th Indiana. Depicting scenes of after-hours horseplay—one Zouave bounds around camp on a pair stilts—they capture the innocence of that early moment in the war.

In his autobiography, Wallace writes that the acclaim the Zouaves won at Romney “astonished nobody so much as ourselves.” But that has the ring of revisionist modesty. Wallace never lacked for confidence, even as an inexperienced volunteer. In the months that followed, he wrote to Susan despairing of the war’s progress (“defeat follows defeat—mismanagement after mismanagement”) and offering detailed explanations of how he would quickly bring the Confederacy to its knees were he in command.

After his success at Romney, Wallace was sent to the war’s western theater, where Grant was preparing for his invasion of Tennessee. Wallace was rising rapidly through the ranks—he was soon promoted to brigadier general—but was impatient for further glory and frequently unhappy with the role he was assigned in the campaign. After being left on guard duty during the army’s initial advance on Fort Donelson, Wallace grumbled to Grant’s aide-de-camp, a Captain Hillyer. “You are not going to be left behind,” Hillyer reassured him. “I know Gen. Grant's views. He intends to give you a chance to be shot in every important move.” Wallace’s eagerness to lead every charge would only make his disappearance at Shiloh that much harder to fathom.

V.

In the spring of 1862, Confederate Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston found himself in an unenviable position. After a series of defeats at the hands of Grant, the rebels had been forced to yield central Tennessee and consolidate their forces in Corinth, Miss., home to a strategic railroad crossing. Johnston commanded a force about 40,000 strong; Grant, encamped 20 miles north on the Tennessee River at Pittsburg Landing and Shiloh Church, had 40,000 men of his own, though he was soon to be reinforced with 35,000 more from Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. The dilemma before Johnston was whether to dig in at Corinth and wait for a superior Union army to advance, or to bring the fight to Grant while the odds were still close to even.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Johnston chose to attack, hoping the element of surprise would tilt the balance in the Confederates’ favor. The relative ease with which Grant had pushed the rebels out of Tennessee had certainly left him complacent. The Union general had decided against entrenching; despite being deep in enemy territory, Grant felt the initiative was his. He did, however, take the precaution of posting Lew Wallace and his 7,500 men 6 miles upriver, where they could keep an eye on the Union flank.

At dawn on the morning of April 6, a patrol of Federal scouts made an unhappy discovery: Thousands of men in gray uniforms advancing on Union soldiers who were just sitting down to breakfast. When word of the attack reached Grant, he ordered Wallace’s Third Division to help turn back the surging Confederates, who were overrunning the hastily assembled Union lines. But Wallace never showed.

Wallace’s detractors would later claim that he had simply lost his way in the Tennessee woods. The truth is more complicated. From Crump’s Landing, where he’d been stationed, there were two roads leading to the Union front: one that hugged the river to Pittsburg Landing, the other a so-called shunpike that led to Shiloh Church, where Sherman was camped. Having surveyed his position in the days prior to the Confederate attack, Wallace had judged the shunpike to be the most passable, and had ordered his cavalry to make further improvements to it in case he needed to march his division quickly to the front.

It was around 11 a.m. when Grant’s summons reached Wallace. Grant’s order, issued verbally and transcribed and delivered by an aide, was lost in the course of the battle; its contents would become the subject of acrimonious debate. Grant claimed that he ordered Wallace to march to Pittsburg Landing, via the river road. Wallace said the order simply instructed him to join up with the right of the Union lines. He took the shunpike.

In her thorough study of Wallace’s military career, Shadow of Shiloh (2010), Gail Stephens makes a compelling case that Wallace’s version of events is the most logical. Timothy B. Smith, a former Park Ranger at the battlefield and a historian who has written extensively on Shiloh, agrees. Wallace may have enjoyed playing armchair general-in-chief in his letters to Susan, but he was not in the habit of disobeying orders, and he’d never shown anything but an appetite for battle. (Grant had made good on his promise to put Wallace in the line of fire at Fort Donelson, and his poised performance had earned him another promotion, to major general, then the highest rank in the army.) Wallace had also made his preference for the shunpike known prior to the Confederate attack, alerting the commander of the neighboring division of his plans to use that road, though that information never reached Grant. It seems likely that either due to a mistaken assumption on Grant’s part (that Wallace would necessarily take the river road), or an omission on the part of his messenger, Wallace believed his orders were to join up with the Union army as quickly as possible, and he chose the road he believed best suited to that task.

What Wallace didn’t know was that by the time his men began marching, the Union army was no longer where he thought it was. Sherman’s position had been overrun, pushed back toward the river. Had Wallace marched to the end of the shunpike he’d have found himself behind enemy lines, cut off from the rest of the Union army. Impatient for Wallace to arrive, Grant sent an aide to speed his progress around 1:00. The aide found him on the shunpike, headed unwittingly toward the Confederate rear. Informed of the new disposition of Union forces, Wallace reversed course and marched his men to the new lines. He arrived as night was falling, too late to fire a shot in the first day’s fight.

VI.

“Well, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” Sherman is said to have remarked to Grant on the night of April 6. “Yes,” Grant replied. “Lick ’em tomorrow, though.” With Wallace’s division finally in place, and Buell’s reinforcements having arrived overnight, Grant unleashed a vicious counterattack on April 7, pushing the rebels back over ground still littered with the dead and dying from the previous day’s fight. Realizing they were now outnumbered, the Confederates beat a retreat in the afternoon.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Shiloh was initially hailed as a Union triumph. Among the Confederate dead was Albert Sidney Johnston, who’d been shot while leading his men in a charge; he would be the highest-ranking officer on either side to be killed in action during the war. But as casualty figures made their way north, newspapers began to portray the battle as a scandalous failure. Questions arose regarding Grant’s competence; there were rumors he’d been drunk during the battle. Lincoln’s famous quip about Grant—“I can’t spare this man; he fights”—came in the wake of Shiloh, as members of Congress, and even the governor of Grant’s home state of Ohio, called for his head.

Grant’s career survived Shiloh; Wallace’s did not. The north needed someone to blame for the heavy casualties, which exceeded those of all the war’s previous battles combined. Wallace’s “dilatoriness” gave Grant cover for his own lack of preparedness, and he implicated Wallace in his official reports. The press, with the help of Grant’s staff, grabbed hold of the story of the missing division. Though Wallace received no official reprimand for his actions, by July he had been relieved of his field command. He spent the rest of 1862 and all of 1863 a general without an army—and worse, for Wallace, a soldier robbed of his honor.

He spent his idle time ill-advisedly, peppering the Union command with letters, maps, and affidavits in an attempt to clear his name. His superiors had other things to worry about, and largely ignored him. At one point Wallace demanded a court of inquiry to investigate his actions at Shiloh. He was only talked out of it by Sherman, who knew Wallace well enough to play expertly on his vanities.

“Keep quiet as possible and trust to opportunity for a becoming sequel to the brilliant beginning you had,” he wrote. “I do not think that Gen. Grant or any officer has unkind feelings toward you, [though some] may have been envious of your early and brilliant career.” Sherman prescribed a course of political expedience: “Avoid all controversies, bear patiently temporary reverses, get into the current events as quick as possible, and hold your horses for the last home stretch.”

VII.

Sherman was right. Wallace did get a chance at redemption in the last home stretch. In the summer of 1864, the Confederate general Jubal Early made a dash for Washington. Grant had left the city largely undefended as he tried to pin Lee down at Petersburg, Va. Wallace, then stationed in Baltimore, was the only man between 13,000 Confederates and the Union capital. Piecing together a rag-tag army of 6,000, he fought a hopeless battle at Monocacy Junction, yet managed in defeat to slow Early’s advance for a crucial day, buying time for Grant to send reinforcements. Were it not for Wallace’s stand, the capital might have fallen. A Navy warship had been idling near the Sixth Street docks to speed Lincoln to safety.

Grant praised Wallace’s actions and warmed to him personally. One day, he invited Wallace to visit him at his headquarters in Virginia. Wallace arrived on his horse Old John, a red bay with white feet and a piebald face. The horse was unusually tall and unusually fast. “Old John in full gallop looked like the incarnation of the wrath to come,” said a friend who had seen him in action. He was beloved by Wallace and by his men. At Fort Donelson, Old John had gone without forage for two days. Wallace’s soldiers crumbled up their hard tack, put it in their hats, and offered it to the general’s horse.

Grant and Wallace rode out to inspect a fort on the left of the Union lines. Grant, a gifted horseman, admired Old John and proposed a race back to camp. Wallace assented, but reined his horse in as the race began. “Let him out!” barked Grant, seeing that he was being afforded a handicap. Wallace did as he was ordered, and though Grant was in a furious gallop, Old John easily sprinted ahead. After a mile or two, Grant called a halt—and offered to buy Old John on the spot. Wallace refused. “Neither love nor money,” he said, “can buy Old John.”

Photo by Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

An account of the impromptu race appeared in the Denver News on Feb. 19, 1905, a few days after Wallace had died. The article was written by J. Farrand Tuttle Jr., the son of the president of Wabash College (located in Wallace’s hometown of Crawfordsville) and a friend of the family. Wallace himself never wrote of the race. Perhaps, in a rare demonstration of tact, he realized it wasn’t to his advantage to brag of beating Grant at a favorite pastime. Or perhaps Tuttle was merely relaying a local legend, a story passed around the Wallace paddock.

Or maybe Wallace did write of the race, but only under the veil of fiction. In every incarnation—novel, play, the 1925 silent film, Wyler’s 1959 spectacle—Ben-Hur’s most celebrated scene has always been the chariot race between Judah and his friend-turned-rival Messala. Early in the story, Messala betrays his boyhood companion, accusing Judah of a crime he didn’t commit: the attempted murder of Judea’s Roman governor. After years of suffering in exile, Judah is afforded an opportunity to avenge himself in the arena. Though Messala is heralded as the greatest charioteer in the empire, he can’t contain the superior horsemanship of Judah, who rides to victory.

It’s hard not to read some wish fulfillment into Judah’s triumph. In the wake of the chariot race, Judah is cleared of the charges that have tarnished his good name, and, having goaded Messala into betting heavily against him, his victory also wins him a fortune to rival the emperor’s. Whatever satisfaction Wallace may have felt racing Grant through the fields of Virginia, it did nothing to improve his reputation or finances. But Ben-Hur would indeed fulfill its author’s wishes, making him fantastically wealthy and dimming the memory of Shiloh—in the public imagination if not Wallace’s own.

VIII.

Ben-Hur wasn’t an immediate success. Sales were slow for the first few months as the book absorbed mixed reviews. With its story of a noble prince endeavoring to save his family and restore his good name (winning the heart of a humble but beautiful Jewess in the process), the novel resembled the romances Wallace had loved as a child, which had long since fallen out of critical favor. With its chariot race and sea battle, it shared something with the dime novels then enjoying wide popularity but no literary esteem. Always a lover of the bold stroke, Wallace had written out his final manuscript in purple ink, a color his critics would have found apt for some of the novel’s loftier passages.

Courtesy of Indiana Historical Society, M0292

Yet what the critics dismissed the reading public soon came to love. Tracking book sales in the 19th century is an inexact science, but the Morsbergers, Wallace’s biographers, estimate that Harper Brothers sold a million copies of the novel between 1880 and 1912; in 1913, Sears, Roebuck ordered a million more, at the time the largest book order ever placed. James David Hart’s The Popular Book: A History of America’s Literary Taste (1950) cites a study conducted in 1893, which found that only three contemporary novels were held by more than 50 percent of public libraries. Ben-Hur was first among them, present in 83 percent of the collections surveyed. (The other two were Little Lord Fauntleroy and Ramona.) “If every American didn’t read the novel, almost everyone was aware of it,” Hart concludes.

Carl Van Doren, in The American Novel (1921), credited Ben-Hur with winning “practically the ultimate victory over village opposition to the novel,” arguing that it was likely the first work of fiction many Americans ever read—or at least the second, after Uncle Tom’s Cabin. As Howard Miller, a professor emeritus of history and religious studies at the University of Texas, has argued, if Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel played a role in dividing the Union in the 1850s, “Wallace's Ben-Hur helped to reunite the nation in the years following Reconstruction.”

Wallace’s novel is about the visceral thrill of vengeance and the spiritual thrill of forgiveness. The chariot race is rightly the most famous scene in Wallace’s novel, a stirring set piece and a surprise if you’ve only ever seen the 1959 movie. In Wyler’s film, Messala outfits his chariot with vicious metal spikes that shred the wooden wheels of his competition. Hollywood’s Messala is a villain through and through, not only responsible for Judah’s exile, but a cheater in the arena too. But in the novel, Judah is the aggressor, running down Messala’s chariot, wrecking it from behind with "the iron-shod point of his axle" and leaving its driver to be trampled by oncoming horses.

Having vanquished Messala in the Antioch arena, Judah sets out for Jerusalem to continue his campaign of retribution, a Jewish William Wallace bent on freeing Judea from its Roman oppressors. But when he arrives in the Holy Land he encounters a rabbi from Nazareth, a man promising not an earthly kingdom but a heavenly one. (Lest Judah have any doubt as to the truth of the rabbi’s teachings, the Nazarene cures his mother and sister of the leprosy they’ve conveniently contracted while wasting away in a Roman jail.) After witnessing Jesus’ arrest and crucifixion, Judah lays down his sword and instead takes up the work of honoring Christ’s message of forbearance. The novel closes with Judah deciding to spend his vast wealth to finance a catacomb where Christian martyrs can be buried and venerated.

Offering the satisfaction of a revenge plot while preaching the gospel of compassion, Ben-Hur resonated with a country that was moving from vengeance to forgiveness itself. The National Soldiers Reunion that Wallace and Ingersoll attended in 1876, at the tail end of Reconstruction, was a strictly Union event, with speeches and parades honoring the North’s just cause. But at the Reunion held just two years later, in Cincinnati, blue mingled with gray: Joe Johnston, John Bell Hood, and Robert E. Lee’s nephew Fitzhugh were among the invitees, and the order of the day was celebrating the heroism of combatants on both sides of the conflict. Ex-rebels were now in the halls of power as well. Wallace’s first official duty as minister to Turkey was to relieve his predecessor—Former Gen. James Longstreet, the trusted Lee lieutenant who had fought at Chickamauga, Antietam, and Gettysburg. After the war, Longstreet had joined the Republican Party and been embraced by his former enemies.

Courtesy of General Lew Wallace Study and Museum

The details of Wallace’s interview with Longstreet are lost to history, but it’s likely the meeting was cordial. Wallace had presided over what would be the Union’s only act of retributive justice after Appomattox: the trial of Henry Wirz, the commandant of Andersonville. If he had any misgivings about executing Wirz (whose degree of culpability for the camp’s atrocities has long been a matter of dispute), he didn’t record them. The drawing he made during the proceedings—of a Union soldier who’d been shot while trying to get a drink of clean water—suggests he was content to see the commandant hang. But by 1880 Wallace harbored no grudge against his former adversaries; on the contrary, ever the romantic, he held the sacrifices they made in high esteem. Speaking at the dedication of the Chickamauga battlefield, he described the Confederates as having made “an honest mistake.” He encouraged his audience to remember “not the cause, but the heroism it invoked.”

Wallace’s admiration for the heroes of the Lost Cause seeped into his novel. As the literary historian David S. Reynolds has noted, in Ben-Hur’s portrait of the Jewish people, readers in the American South could find a subjugated, slave-holding, and yet noble people sympathetically described. And indeed, despite being authored by a Union general, the book found an avid readership in the former Confederacy, making Ben-Hur among the first mass entertainments to transfix all corners of the reborn nation. One of the earliest fan letters Wallace received came from Paul Hamilton Hayne, a respected poet and editor and a Confederate veteran. “It is—me judice—a noble and very powerful prose poem!” Hayne wrote. “Simple, straightforward, but eloquent.”

Wallace was thrilled to learn that a former rebel had enjoyed his novel. In his reply to Hayne, he expressed delight at receiving such high praise from “the Singer of the South.” He then delicately asked the poet if he had any objections to Wallace’s publishing the letter. After his long string of financial failures, he was eager to join in the prosperity of the nascent Gilded Age, and hoped testimonials like Hayne’s would help him move copies.

For Wallace as for many Americans, the profit motive had extinguished any lingering sectional enmity. That Judah Ben-Hur finds Christ and wins a great fortune was surely not lost on the novel’s newly affluent readers, North and South. (The most popular of the many of novels of Christ that followed in Ben-Hur’s wake picked up this theme; In His Steps (1897) imagined a small town whose citizens earn spiritual and financial reward by constantly asking themselves “what would Jesus do?”)

Ben-Hur’s action-packed middle section undoubtedly accounted for much of its popularity, but the novel also benefitted greatly from its interpretation of the life of Christ, which opens and closes the novel. As Reynolds demonstrates in his study of American religious literature, Faith in Fiction (1981), Biblical novels had already begun to flourish in America by the time Wallace sat down to write Ben-Hur, books like David Ingraham’s epistolary novel The Prince of the House of David (1855) and William Ware’s Julian: Or, Scenes in Judea (1856). But Ben-Hur was among the first American novels to make Jesus a full-fledged character in its story.

Wallace was in some ways cautious in his treatment of Jesus: His speaking part is small, and the dialog is taken verbatim from the King James Bible. But in other ways Wallace was daring. At the outset of Judah’s trials, as he’s being marched off to slavery, a young man in Nazareth wordlessly offers the prisoner a drink of water:

“...looking up, [Judah] saw a face he never forgot—the face of a boy about his own age, shaded by locks of yellowish bright chestnut hair; a face lighted by dark-blue eyes, at the time so soft, so appealing, so full of love and holy purpose, that they had all the power of command and will.”

The scene is remarkable for having been created out of whole cloth; inventing occurrences in the life of Jesus simply wasn’t done in 19th-century Biblical fiction. It’s also notable for its detailed physical portrait of Christ, who is described as he’d rarely been before, in the Gospels or elsewhere. Wallace wrote of the pallor of Jesus’ complexion, the “reddish golden” highlights the sun leaves in that chestnut hair, and even the impressive length of his eyelashes. Iras, the novel’s femme fatale, derisively refers to Jesus as “the man with the woman’s face”—perhaps with a touch of jealousy.

Wallace was equally attentive to the geography, topography, and even flora and fauna of ancient Judea. (Rarely in American fiction has the camel been described so extravagantly.) He spent long hours researching the setting of his story, travelling to libraries in Washington, D.C., New York, and Boston. When he later traveled to Jerusalem during his term as minister to Turkey, he congratulated himself on his accuracy: “At every point of the journey over which I traced [Judah’s] steps to Jerusalem, I found the descriptive details true to the existing objects and scenes.”

Wallace’s careful descriptions are not incidental to the novel’s appeal. He made the figure of Christ, and the times in which he lived, come alive for readers at a moment when faith was under assault, by the speeches of Robert Ingersoll, the writings of Charles Darwin, and the lingering trauma of the Civil War. “The horrors of battle and the magnitude of the carnage were difficult to put aside,” writes Drew Gilpin Faust in This Republic of Suffering (2008). “The force of loss left even many believers unable to abandon lingering uncertainties about God’s benevolence.” One of the only rivals to Ben-Hur’s popularity in the 19th century was Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’ The Gates Ajar (1868), which painted for its readers a detailed, and comforting, portrait of the heaven that awaited the thousands of dead soldiers. In Ben-Hur, Wallace gave readers a flesh-and-blood Jesus who walked through a realistically rendered landscape, reassuring the wavering reader of Christ’s divinity by making the case for his historicity.

Letters Wallace received from readers attest to the novel’s descriptive power. “The messiah appears before us as I always wished him depicted to men,” wrote a Roman Catholic priest. “The various descriptions surpassed in their attraction, glowing colors, and truthfulness all I have ever read before.” According to a contemporary newspaper account, pastors and school superintendents were fond of pointing out that “the most vivid picture of the Holy Land in the time of Christ was in Ben-Hur.” As a result, “no boy who went to Sunday school could have escaped the story if he tried.” (Teachers who ignored the novel may have done so at their peril. In Anne of Green Gables (1908), the young heroine sneaks Ben-Hur into her Canadian history class. “I had just got to the chariot race when school went in,” she later confesses. “I was simply wild to know how it turned out.”)

The novel had a strong effect on its readers, young and old. “I feel that I am a better man for having read it,” wrote Samuel Moore to the author, on the stationery of Moore, Morgan & Co, Wholesale Dry Goods and Notions of Lafayette, Ind. “In my knowledge of books it has but one superior, and that is The Book.” For others, it accomplished what even the Bible could not. Perhaps the most remarkable response Wallace received was from a man named George Parrish, a self-described “drunkard” who had lost everything to his addiction. “I had no future to hope for,” he wrote to Wallace from a YMCA in Kewanee, Ill. “No past but of which I was ashamed.” Ben-Hur, however, inspired Parrish to find religion, and recovery. “It seemed to bring Christ home to me as nothing else could,” he explained, and “resting on his strength, I stood up again in this community and was a man.” Parrish wrote that it had been a year since he read the novel, and he’d “faltered” not once in that time. “I want to thank you for that book,” he wrote to Wallace. “Thank you as a man who has come up from midnight into midday.”

IX.

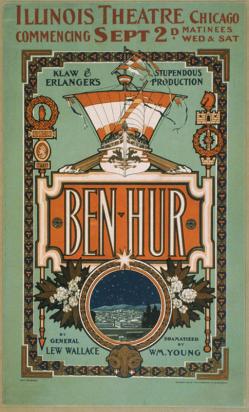

As the novel’s popularity spread, theater companies hoping to bring Ben-Hur to Broadway besieged author and publisher with lucrative offers. But Wallace was reluctant. He worried that audiences would not permit a depiction of Christ on stage. (In 1879, a passion play in San Francisco had landed its star in jail, still wearing his halo.) But years of lobbying by the New York producers Marc Klaw and Abraham Erlanger eventually broke him down. The agreement between the parties stipulated that no actor would play the role of Jesus. He would instead be represented by a 25,000-candlepower light.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

The play was a runaway hit, a fixture of Broadway and the regional theater for the next 20 years. And like the novel, it soon overcame any clerical objections. One clergyman wrote to Wallace of “the immense missionary work Ben-Hur has done. I am sure the author will receive the blessing of the Master of the Harvest for the countess souls his labor has garnered.” William Jennings Bryan called it “the greatest play on stage when measured by its religious tone and moral effect.” The evangelist Billy Sunday liked it so much that he volunteered his services as a spokesman.

And it wasn’t just a hit in New York; like the novel, it found a truly national audience. Regional theaters were so eager to host the show that they conducted renovations in order to accommodate the elaborate production. In the 1904-05 season alone it played in Milwaukee, Indianapolis, Columbus, St. Louis, Dallas, Austin, San Antonio, Galveston, Houston, New Orleans, Mobile, Birmingham, Atlanta, Cincinnati, Chicago, Louisville, Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Washington, and the former Confederate capital, Richmond. If the novel had introduced many Americans to fiction-reading, the play introduced even more to the theater. Newspaper accounts of the traveling production describe audiences filled with first-timers, many of them devout churchgoers who’d previously been suspicious of the stage. Texas’ Howard Miller, an expert on the play, points to newspaper coverage of a 1907 performance in Toledo, Ohio. When the curtain fell after the crucifixion, many in the rapt audience failed to applaud—not because they hadn’t enjoyed the production, but because they weren’t accustomed to clapping for Christ.

Klaw and Erlanger had created an impressive spectacle, with a massive cast, a reverent treatment of the Christ story, and exhilarating interpretations of the novel’s action scenes. The chariot race was performed using real horses, which galloped on hidden treadmills—a not-unprecedented trick, but a breathtaking one nonetheless. As had been the case with its source, the play failed to impress critics (“the piece rises above the level of ordinary melodrama in only two or three scenes,” wrote the New York Times), but audiences couldn’t stay away. Miller notes that for many Americans, seeing Ben-Hur became an annual rite, akin to Christmastime pilgrimages to The Nutcracker today. Irving McKee, Wallace’s first biographer, estimated that by the time the show’s two-decade run came to an end, 20 million people had seen it.

Wallace was awestruck when he first saw the Ben-Hur stage sets. “My God,” he said. “Did I set all of this in motion?” What he had set in motion was an entertainment that had reached more Americans than perhaps any other story save the original tale of the Christ. Though he couldn’t know it, Ben-Hur’s success on stage augured its future as a blockbuster silent film in 1925 and feature film in 1959—few folk stories in American history have proved as durable. Wallace, however, remained convinced that his legacy had been written not under the Ben-Hur beech but on the road to Shiloh Church.

X.

In 1884, Century Magazine commissioned a series of firsthand accounts of Civil War battles. With his literary star on the rise, Wallace was asked to contribute one of the first, on Fort Donelson. His article appeared in December, alongside serial installments of Huckleberry Finn and William Dean Howells’ The Rise of Silas Lapham. Whatever satisfaction Wallace took in keeping such august company was soon replaced by apprehension, however, when he learned that Grant, deeply in debt and suffering from cancer, had also agreed to write for the Century series after years of refusing to revisit the war. His subject would be Shiloh. Wallace’s ignominious role in the fight threatened to return to the national stage.

Photo by Popperfoto/Getty Images

Wallace wrote Grant imploring him to use the article as an occasion to absolve him of wrongdoing. The letter left no argument for his blamelessness unexplored. He reminded Grant that he’d fought bravely at Donelson and acted with dispatch to save Washington in 1864. He asked Grant to consider what motive he possibly could have had to “play you falsely that day.” He even suggested that had Grant’s aide, Rowley, not caught up to him on the shunpike, Wallace might have saved the day at Shiloh. In wistful detail, he painted a counterfactual history of April 6 in which he bravely charged the Confederate lines from the rear. It reads like a page out of one of his novels:

“The enemy had used the last of his reserves. I would have taken the bluff on which Sherman had been camped in the morning and without opposition affected my deployment. The first of the rebels struck would have been the horde plundering the sutlers and drinking in the streets of the camp. Their fears would have magnified my command …”

Not trusting that his letter would have its desired effect, Wallace also visited Grant to plead with him in person. His talent for horning in on history did not fail him. He arrived on the same day that Twain was paying a call to the former president, bearing an offer to publish his memoirs (and to pay his friend a handsome 70 percent royalty). “There’s many a woman in this land that would like to be in my place,” said Julia Grant when the two callers met in the parlor, “and be able to tell her children that she once sat elbow to elbow with two such great authors as Mark Twain and General Wallace.”

Only one of the great authors got his wish that day. Grant’s article not only failed to absolve Wallace, it reaffirmed his conviction that the Third Division had taken the wrong road and that its absence had cost the Union dearly on the first day of fighting. It was worse than perhaps even Wallace had dared to fear.

Shortly after the article was published, however, Grant had a change of heart. The widow of a general who had been killed in action at Shiloh had come across a letter from Wallace to her husband, dated April 5, 1862. It was the letter Wallace had sent to the commander of the neighboring division at Shiloh, announcing his plans to use the shunpike should trouble arise. It convinced Grant of what Wallace had long argued. The letter “modifies very materially what I have said, and what has been said by others, about the conduct of General Lew. Wallace at the battle of Shiloh,” Grant wrote. He still maintained that he’d ordered Wallace to take the river road, but allowed that his wishes may have been lost in the fog of war: “My order was verbal, and to a staff officer who was to deliver it to General Wallace, so that I am not competent to say just what order the general actually received.”

It was the vindication Wallace had longed for since 1862. But even this failed to satisfy him. The Century article, with its repetition of the standard account of Wallace’s mistakes, became the Shiloh chapter of Grant’s memoirs. The exoneration appeared as a footnote, one that Wallace worried would be ignored by most readers. Rightly, as it would turn out: A Blaze of Glory, Jeff Shaara’s recent novel of Shiloh, and The Man Who Saved the Union, H.W. Brands’ recent biography of Grant, both describe Wallace as having been lost on April 6.

Unsatisfied with Grant’s pardon, Wallace continued his efforts to clear his name, taking any chance he could get to refight the battle. In 1888, Benjamin Harrison tapped his fellow Hoosier to write his campaign biography, hoping to leverage some of Wallace’s celebrity for his presidential run. (“That is excellent,” wrote a waggish friend of Harrison’s when Wallace accepted the assignment. “He did so well on Ben-Hur that we can trust him with Ben Him.”) Wallace began the chapter on Harrison’s Civil War service with what he euphemistically called “the great Union victory” at Shiloh, taking a few pot shots at the high command before moving on to battles in which the subject of his biography actually took part. In April 1862, when Shiloh was fought, Benjamin Harrison was still practicing law in Indianapolis.

Wallace just couldn’t let the battle go. In a moving letter to Susan from the waning days of his appointment in Turkey, Wallace reflected on his long, varied career and looked forward to passing his final days “in the old man’s gown and slippers, helping the cat keep the fireplace warm.” He was proud of the diplomatic work he’d done, and pleased by Ben-Hur’s success. Only one cloud hung over his head: “Shiloh and its slanders! Will the world ever acquit me of them?” he wrote. “If I were guilty I would not feel them as keenly.”

XI.

In the spring of 1898, as tensions between the United States and Spain mounted, Lew Wallace sent a telegram to Secretary of War Russell Alger. He offered to raise a brigade, or even a division, of volunteer troops from the black population of the Midwest and lead them into battle himself. “The most magnificent regiments in the Turkish army consist of negroes,” he wrote. “I think it could be duplicated in our country.” Alger’s reply was prompt and polite, thanking the general for his “patriotic action in this matter.” But the McKinley administration had little need for a 71-year-old general. “In the event of war,” Alger wrote. “You will be duly notified.” Don’t telegram us, we’ll telegram you.

Courtesy of Carol M. Highsmith/Library of Congress

Wallace’s attempt to join the war effort may look like a publicity stunt, but his offer seems to have been made in earnest. As the Morsbergers document in their biography, Wallace used all of his political capital in an attempt to win a commission, sending a wave of friends in Washington to petition the McKinley administration on his behalf.

The Civil War was fading further into memory, and its events took on a rose-colored hue. Though Grant’s hard-nosed essay on Shiloh was a notable exception, Century Magazine’s “Battles and Leaders” series had tended toward the celebration of great men committing valorous acts. A new generation of young men now longed for a chance to demonstrate their courage in a war with Spain, and indeed a renewed martial spirit was likely a factor in Ben-Hur’s popularity in the last decade of the 19th century. Judah’s manly exploits appealed to Gilded Age Americans wary of what the historian Jackson Lears has termed “overcivilization”: the soft, domestic comforts of bourgeois metropolitan life in a country with a now-closed frontier.

Some of Wallace’s comrades-in-arms rejected post-war sentimentalism, perhaps none so completely as Ambrose Bierce, whose essay “What I Saw of Shiloh” (1881) described the battle in ghastly detail. He recalled the sight of a sergeant, still breathing “in convulsive, rattling snorts” despite having been shot through the skull. “I had not previously known one could get on, even in this unsatisfactory fashion, with so little brain,” he wrote. To Bierce, death was “a dismal thing, hideous in all its manifestations.” But Wallace had never lost the romantic view of war that had taken hold of him as a boy. He had his doubts about America’s nascent imperialism, but if there was to be a fight, he wanted to be in the thick of it.

“How many there are who spend their youth yearning and fighting to write their names in history,” observes the narrator of A Prince of India, Wallace’s 1893 follow-up to Ben-Hur, “then spend their old age shuddering to read them there!" Wallace still shuddered at the way his name had been written into history, and he surely also saw the war with Spain as one final chance at a revision. When McKinley failed to commission him a general, he visited his local recruiting office and attempted to enlist as a private. “If I can not serve in the one capacity, I should be happy to serve in the other,” Wallace told the Indianapolis News, calling the rank of private “no less honorable” than that of major general. The recruiter, citing his age, turned him away.

XII.

Wallace died of stomach cancer on Feb. 15, 1905, at the age of 77. In the days following his death, nearly every newspaper in the country carried an obituary, many of them as lead stories that jumped to full-page spreads. The Cincinnati Enquirer announced the news with a headline overwrought even by fin de siècle standards, though not atypical of the coverage:

Ended

Is the Chariot Race

In Which He Drove Pegasus to Lasting Fame

And General Lew Wallace Succumbs to Death

Author of Ben-Hur Had Hoped to Be Restored

By the Gentler Agencies of Spring

But Failed to Muster the Necessary Strength

To Resist Winter’s Rigor and the Encroachment of Disease—Sketch of His Career

Some of these career sketches revisited the scandal of Shiloh, but the success of Ben-Hur was the dominant theme of most. “Throughout the rank and file of our steady churchgoing people the man who is ignorant of Ben-Hur, who cannot relay vividly every point of the chariot race, is set down as beyond the pale in both literature and religion,” wrote the New York Post. “Shakespeare and Milton are above the range of honest folk, the Bible they are often content to take at second hand, but Ben-Hur brings grandeur nearer our common dust.”

Wallace is buried in his hometown of Crawfordsville, in a cemetery near Indiana Route 231. Over his grave stands a gaudy marker of which he surely would have approved—an obelisk draped in a granite rendering of Old Glory. His epitaph is a line taken from Ben-Hur: “I would not give one hour of life as a Soul for a thousand years of life as a man.”

Photo by John Swansburg

That line is spoken by Balthazar, one of the three Wise Men who arrive in Bethlehem to herald the virgin birth, and, in Wallace’s novel, the man who shepherds Judah Ben-Hur toward a belief in Christ’s divinity. Wallace professed that writing the novel led him to his own belief in Christ, though he never joined a church. (“Not that churches are objectionable to me, but simply because my freedom is enjoyable,” he explained.) There’s no reason to doubt the sincerity of Wallace’s faith, and yet it’s hard to believe that he ever came to share Balthazar’s disdain for earthly endeavor. Few men in American history have made more of their time in this life, or been so concerned with the legacy they were leaving behind.

It would surely please Wallace to know that he achieved a kind of immortality in this world. Though his name is not well remembered today, his novel has never disappeared from the American landscape. Earlier this month, scholars convened at Rutgers for a daylong conference on the book, covering everything from its theology to its geology. This Easter weekend, the Ovation channel will air the American premiere of an excellent Canadian miniseries adaptation of Ben-Hur, starring, among others, Hugh Bonneville of Downton Abbey. MGM, meanwhile, has just bought a script for a new feature film version. In the item reporting MGM’s acquisition, Deadline Hollywood noted that scripts about Pontius Pilate, Noah, and two about Moses have lately attracted attention from powerbrokers like Brad Pitt, Ridley Scott, and Steven Spielberg—attention that is sure to intensify in the wake of the record-setting ratings success of the History Channel’s The Bible miniseries. That Americans can’t resist a Biblical epic may seem intuitive in 2013, but it wasn’t in 1876. All of these productions owe something to Lew Wallace.

Wallace, in turn, surely owed some part of his literary success to his military failure. Unable to live up to his romantic ideal of the gallant soldier, he was left to imagine such a soldier in his fiction. In Judah Ben-Hur, he created the hero he wished he’d been at Shiloh, a paragon of strength and pluck.

Wallace returned to Shiloh several times after the war, surveying the land for new evidence to support his version of events. During one trip, made after Ben-Hur had won him fame and fortune, he found the tree next to which he’d camped one night. It had been a sapling then; it was now full-grown. Wallace broke a branch from its trunk and sent it off to Tiffany & Co., in New York, which outfitted it with an elegant ivory handle. Cane or scepter? A symbol of frailty or power? It could be either. Shiloh had laid Wallace low—and set him on his roundabout road to glory.

Courtesy of General Lew Wallace Study and Museum