In Defense of Drones

They're the worst form of war, except for all the others.

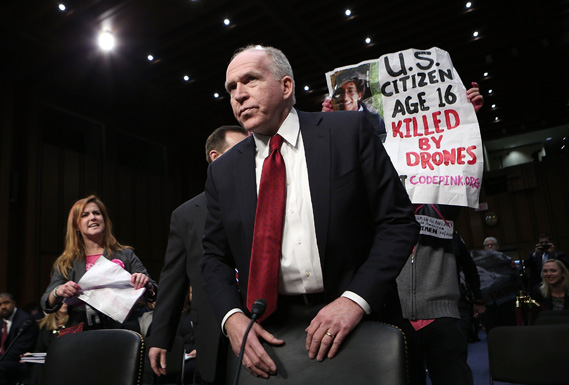

Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images

“UN: Drones killed more Afghan civilians in 2012,” says the Associated Press headline. The article begins: “The number of U.S. drone strikes in Afghanistan jumped 72 percent in 2012, killing at least 16 civilians in a sharp increase from the previous year.” The message seems clear: More Afghans are dying, because drones kill civilians.

Wrong. Drones kill fewer civilians, as a percentage of total fatalities, than any other military weapon. They’re the worst form of warfare in the history of the world, except for all the others.

Start with that U.N. report. Afghan civilian casualties caused by the United States and its allies didn’t go up last year. They fell 46 percent. Specifically, civilian casualties from “aerial attacks” fell 42 percent. Why? Look at the incident featured in the U.N. report (Page 31) as an example of sloppy targeting. “I heard the bombing at approximately 4:00 am,” says an eyewitness. “After we found the dead and injured girls, the jet planes attacked us with heavy machine guns and another woman was killed.”

Jet planes. Machine guns. Bombing. Drones aren’t the problem. Bombs are the problem.

Look at last year’s tally of air missions in Afghanistan. Drone strikes went way up. According to the U.N. report, drones released 212 more weapons over Afghanistan in 2012 than they did in 2011. Meanwhile, manned airstrikes went down. Result? Fifteen more civilians died in drone strikes, and 124 fewer died in manned aircraft operations. That’s a net saving of 109 lives.

On Monday, Afghan President Hamid Karzai banned his security forces from requesting NATO airstrikes in residential areas. Why? Because a week ago, an airstrike killed 10 civilians. What kind of airstrike? Bombs.

In war after war, it’s the same gruesome story: crude weapons, dead innocents. In World War II, civilian deaths, as a percentage of total war fatalities, were estimated at 40 to 67 percent. In Korea, they were reckoned at 70 percent. In Vietnam, by some calculations, one civilian died for every two enemy combatants we exterminated. In the Persian Gulf War, despite initial claims of a vast Iraqi death toll, we may have killed only one or two Iraqi soldiers for every dead Iraqi civilian. In Kosovo, a postwar commission found that NATO’s bombing campaign killed about 500 Serbian civilians, almost matching the 600 enemy soldiers who died in action. In Afghanistan, the civilian death toll from 2001 to 2011 has been ballparked at anywhere from 60 to 150 percent of the Taliban body count. In Iraq, more than 120,000 civilians have been killed since the 2003 invasion. That’s more than five times the number of fatalities among insurgents and soldiers of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

Why so many noncombatant deaths? Study the record. In Vietnam, aerial bombing killed more than 50,000 North Vietnamese civilians by 1969. Each year of that war, the least discriminate weapons—bombs, shells, mines, mortars—caused more civilian injuries than guns and grenades. In Kosovo, the munitions were more precise, and NATO tried to be careful. But according to a postwar report by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, NATO’s insistence on flying its planes no lower than 15,000 feet—a rule adopted “to minimize the risk of casualties to itself”—“may have meant the target could not be verified with the naked eye.” In Afghanistan, a 2008 report by Human Rights Watch found that “civilian casualties rarely occur during planned airstrikes on suspected Taliban targets.” Instead, “High civilian loss of life during airstrikes has almost always occurred during the fluid, rapid-response strikes, often carried out in support of ground troops after they came under insurgent attack.”

Drones can overcome these problems. You can fly them low without fear of losing your life. You can study your target carefully instead of reacting in the heat of the moment. You can watch and guide the missiles all the way down. Even the substitution of missiles for bombs saves lives. Look at the data from Iraq: In incidents that claimed civilian lives, the weapon with the highest body count per incident was suicide bombing. The second most deadly weapon was aerial bombing by coalition forces. By comparison, missile strikes killed fewer than half as many civilians per error.

How do drones measure up? Three organizations have tracked their performance in Pakistan. Since 2006, Long War Journal says the drones have killed 150 civilians, compared to some 2,500 members of al-Qaida or the Taliban. That’s a civilian death rate of 6 percent.* From 2010 to 2012, LWJ counts 48 civilian and about 1,500 Taliban/al-Qaida fatalities. That’s a rate of 3 percent.

The New America Foundation uses less charitable accounting methods. But even if you adopt NAF’s high-end estimate, the drones have killed 305 civilians, compared to some 1,500 to 2,700 militants, which puts the long-term civilian death rate at about 15 percent. NAF’s figures, like LWJ’s, imply that the rate has improved: From 2010 to 2012, NAF’s high-end civilian casualty tally is 90, and its midpoint estimate of dead militants is 1,410, yielding a civilian death rate of 6 percent.

The highest reckoning of noncombatant killings comes from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Since 2004, BIJ counts 473 to 893 civilian deaths, against a background of roughly 2,600 to 3,500 total killings. Using BIJ’s high-end estimates, if every fatality other than a civilian is a militant, the long-term civilian death rate is 35 percent. Using BIJ’s low-end estimates, the rate is 22 percent. But again, if you break down the data by year, they point to radical improvement. From 2010 to 2012, BIJ’s count of 172 civilian deaths, against a background of 1,616 total fatalities, yields a civilian death rate of 12 percent.

In Yemen, NAF says drones have killed 646 to 928 people, of which 623 to 860 were militants. If you assume that everyone not classified as a militant was a civilian, that’s a civilian death rate of 4 to 8 percent. LWJ’s Yemen numbers are less kind: It counts 35 civilian deaths and 274 enemy deaths in 2011 and 2012, yielding a rate of 13 percent. BIJ hasn’t tallied its Yemen data, but if you add up all the fatalities it counted as civilian in 2012, you get a civilian death rate of 10 to 11 percent. (For one strike last May, which several witnesses attributed to a plane, BIJ counts more noncombatant deaths than total deaths. If you don’t include those fatalities in the drone column, the civilian death rate for 2012 is just 7 percent.)

You can argue over which of these counting systems to believe. But the takeaway is obvious: Drones kill a lower ratio of civilians to combatants than we’ve seen in any recent war. Granted, many civilians in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other such wars were killed by our enemies rather than by us. But that’s part of the equation. One reason to prefer drones is that when you send troops, fighting breaks out, and the longer the fighting goes on, the more innocent people die. Drones are like laparoscopic surgery: They minimize the entry wound and the risk of infection.

Over the years, I’ve shared many worries about the rise of drones: the illusion of withdrawal, the militarization of the CIA, the corruption of law, the evasion of congressional restraint, the risk of mission creep, and the proliferation of signature strikes. But civilian casualties? That’s not an argument against drones. It’s the best thing about them.

Correction, March 13, 2013: This article originally used the phrase "civilian casualty rate" to describe the ratio of civilian deaths to enemy combatant deaths. Casualties include injuries as well as deaths. Accordingly, the phrase has been changed to "civilian death rate" in all instances.

William Saletan's latest short takes on the news, via Twitter: