A year ago, the chief military lawyer of the United States promised Americans that the Obama administration, unlike the Bush administration, wouldn’t bend the law to suit its wishes. “In the conflict against an unconventional enemy such as al-Qaida, we must consistently apply conventional legal principles,” said Jeh Johnson, the Defense Department’s general counsel. “We must not make it up to suit the moment. Against an unconventional enemy that observes no borders and does not play by the rules, we must guard against aggressive interpretations of our authorities that will discredit our efforts, provoke controversy and invite challenge.”

Today, that promise is roadkill. To justify drone strikes against al-Qaida and its “associates,” the United States has redefined every legal term that got in the way. We have done this explicitly because honoring the original meanings of these terms would cost us too much.

White House counterterrorism adviser John Brennan made the first public move in September 2011. The United States would strike only to avert an “imminent” attack, but with a caveat:

We are finding increasing recognition in the international community that a more flexible understanding of “imminence” may be appropriate when dealing with terrorist groups, in part because threats posed by non-state actors do not present themselves in the ways that evidenced imminence in more traditional conflicts. After all, al-Qaida does not follow a traditional command structure, wear uniforms, carry its arms openly, or mass its troops at the borders of the nations it attacks. Nonetheless, it possesses the demonstrated capability to strike with little notice and cause significant civilian or military casualties.

Al-Qaida was too good at concealing imminent attacks. Therefore, all its attacks would now be classified as imminent. In March 2012, two weeks after Johnson pledged not to reinterpret the law to suit present needs, Attorney General Eric Holder declared that requiring the United States to wait until “the precise time, place, and manner of an attack become clear … would create an unacceptably high risk that our efforts would fail, and that Americans would be killed.” To save lives and win the war, the meaning of imminent had to change.

The meaning of sovereignty had to change as well. “We are at war with a stateless enemy, prone to shifting operations from country to country,” said Holder. “International legal principles, including respect for another nation’s sovereignty, constrain our ability to act unilaterally. But the use of force in foreign territory would be consistent with these international legal principles if conducted, for example, with the consent of the nation involved—or after a determination that the nation is unable or unwilling to deal effectively with a threat to the United States.” Under this interpretation, a country infected by militants associated with al-Qaida could consent to American military action, in which case the United States was entitled to strike. Or it could forbid American military action, in which case the United States was entitled to strike. Or it could offer to oust the militants itself, in which case, if it failed, the United States was entitled to strike.

Holder promised that if the targeted person was an American citizen, the United States would use lethal force only if “capture is not feasible.” But that term, too, had to be updated. “Whether the capture of a U.S. citizen terrorist is feasible,” Holder argued, “may depend on, among other things, whether capture can be accomplished in the window of time available to prevent an attack and without undue risk to civilians or to U.S. personnel.” Any delay in pulling the trigger might lead to an imminent attack, given the new definition of imminent. Furthermore, any attempt to capture the targeted person might endanger members of the capture team. Therefore, fire away.

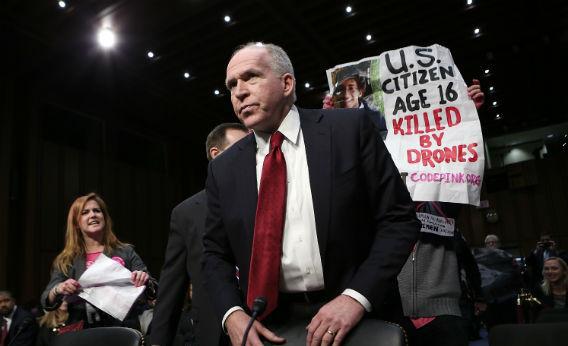

A month after Holder’s speech, Brennan expanded on the feasibility standard: “These terrorists are skilled at seeking remote, inhospitable terrain—places where the United States and our partners simply do not have the ability to arrest or capture them. At other times, our forces might have the ability to attempt capture, but only by putting the lives of our personnel at too great a risk.” By this calculus, capture was almost never feasible. That’s why Brennan, in his April 2012 address and in his confirmation hearing yesterday for CIA director, failed to name more than one al-Qaida associate the United States had captured, rather than killed, during Obama’s presidency.

Last week, to assuage critics of the targeted killing program, the administration leaked a Justice Department “white paper” summarizing its new interpretations. (See these incisive critiques by Slate’s Eric Posner and Fred Kaplan.) Imminent, for instance, will no longer be understood to require “clear evidence that a specific attack on U.S. persons and interests will take place in the immediate future,” since this definition “would not allow the United States sufficient time to defend itself.” The paper concedes that any official who authorizes a strike must be “informed.” But such questions, according to Johnson and Holder, “are not appropriate for submission to a court,” since they “depend on expertise and immediate access to information that only the Executive Branch may possess in real time.” You can’t judge whether the decision to strike was sufficiently informed, because we won’t inform you.

At yesterday’s hearing, Brennan clarified nothing. In written questions submitted beforehand, the Senate Intelligence Committee asked him how the administration decides that a possible terrorist attack is sufficiently “imminent” to warrant a strike. Brennan simply quoted Holder’s redefinition of the word. Beyond that, Brennan said the standard was too “fact-specific” to spell out. But he assured senators that the United States pulls the trigger only when “the threat is so grave and serious, as well as imminent, that we have no recourse except to take this action that may involve a lethal strike.”

I’d like to believe that. But the record tells a simpler story. To minimize any risk to Americans, our government will find a way around whatever gets in the way, including our language and our law.

William Saletan’s latest short takes on the news, via Twitter: