Cuckoo for Cocoa

Are women really crazy about chocolate?

During the week leading up to Valentine’s Day, Americans will purchase more than 60 million pounds of chocolate—and more than 75 percent of it will be given by men to women. No doubt, most of the heterosexual men who give chocolate to their partners see it as a token of affection, a way to strengthen their romantic bonds, a gesture to show their partners that they are loved. Plus, it’s kind of a no-brainer—all women love chocolate, right?

The stereotype that women are crazy about chocolate has become virtually axiomatic. Many women happily propagate the idea that chocolate is feminine fare: Bookstores teem with cocoa-themed titles written by and geared toward women, be they heartwarming (Chocolate for a Woman’s Soul), prescriptive (The Chocolate Lovers’ Diet), or sardonic (Give the Bitch Her Chocolate). Profiles of female celebrities routinely feature confessions of chocoholism—or at least occasional indulgences in the dark stuff. Even women who are keenly aware of stereotypes and double standards have a soft spot for chocolate; feminist blogs Jezebel and the Hairpin regularly feature posts on chocolate, with varying degrees of tongue-in-cheekness. Where did this stereotype come from?

It certainly didn’t come from science. Research on whether women like chocolate more than men has yielded mixed results, in part because craving—the term researchers tend to use when talking about chocolate proclivities—is an inherently subjective phenomenon. Some surveys have revealed virtually no difference in chocolate cravings between men and women, but others indicate a significant gender discrepancy. There’s no hormonal reason for women to like chocolate more than men (chocolate cravings don’t decrease much after menopause) but some studies indicate that American women crave chocolate more than women in other countries, suggesting that cultural factors are at play.

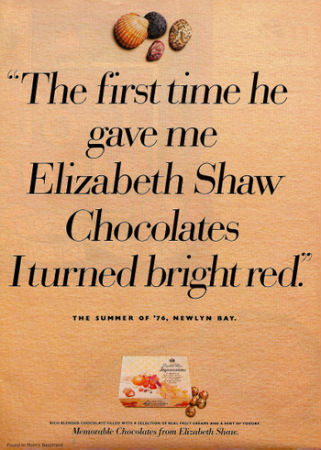

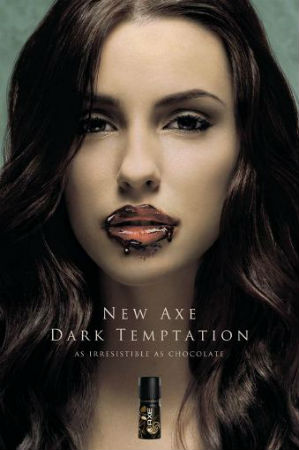

The more realistic culprit for the perceived link between women and chocolate is marketing. Television commercials and print ads often show women’s need for chocolate as desperate and animalistic. (For a few hilarious examples of this, browse through Slate’s slide show of stock photos of women eating chocolate.) What’s more, advertisers routinely depict the pleasure of eating chocolate as not only equal to the pleasure of sex, but identical to the pleasure of sex or redeemable for the pleasure of sex.

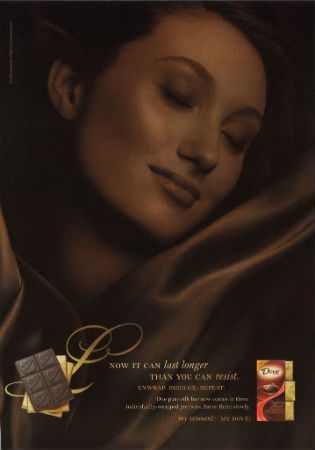

As an example of the first trope—chocolate as sexual bliss conveniently wrapped up in foil—consider a 2010 Dove Chocolate commercial, which features a beautiful, scantily clad woman lounging alone in a courtyard as sultry guitar music plays. She bites into a piece of chocolate, and a magical chocolate-colored piece of silk flies toward her and rubs itself against her bare skin as she smiles. This commercial, like others of its ilk, portrays women as bored and unsatisfied until chocolate enters their lives and fulfills all their desires.

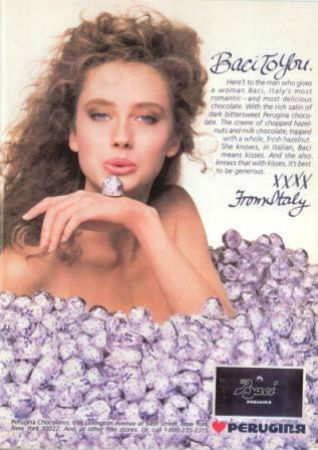

Other ads take the ostensibly humorous tack of portraying the relationship between chocolate and sex as transactional. In these ads, men give chocolate to women and suddenly find them not only amenable to sex but aggressively interested in it. The most ridiculous example of this kind of ad—and possibly the most ridiculous example of any ad ever made—is Axe’s infamous Chocolate Man ad, in which a white man is magically transformed into chocolate and induces a frenzy of lust in every woman he encounters.

Though the notion that women become raging sluts at the sight of chocolate is relatively new, the relationship between chocolate and sex isn’t. The Aztecs are said to have ritualistically eaten cacao off each other’s skin during sex, and the Aztec emperor Montezuma reportedly drank copious quantities of a chocolate-based beverage to enhance his virility. When chocolate crossed the Atlantic in the 16th century, its salacious reputation followed it, fed by missionaries’ recollections of watching chocolate-fueled Aztec orgies.

According to Mort Rosenblum, the author of Chocolate: A Bittersweet Saga of Dark and Light, when the spoils of the New World arrived in Spain, “The men drank coffee and stronger stuff, and the women drank chocolate.” But in Enlightenment-era Europe chocolate was still also seen as an arouser for men. Giacomo Casanova reputedly drank it in the lead-up to assignations, and Madame du Barry, Louis XV’s mistress, supposedly fed chocolate to her lovers to improve their potency. (Racial anxieties surrounding chocolate—typified by that awful Axe ad—also date to Enlightenment-era Europe; Rosenblum tells an anecdote about Madame de Sevigny “writing to her daughter saying, ‘Don’t drink too much [chocolate]; Madame So-and-So drank it, and her child came out black as the devil.’”)

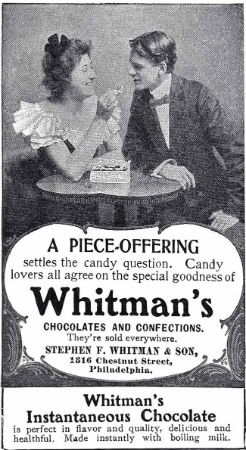

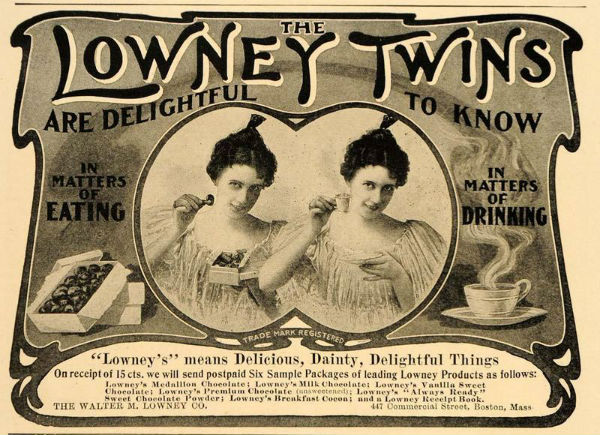

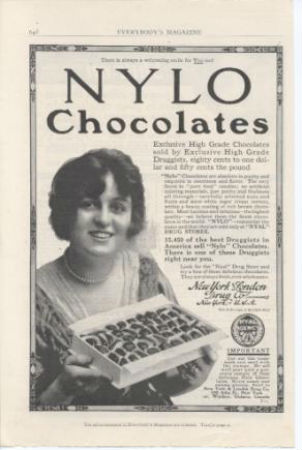

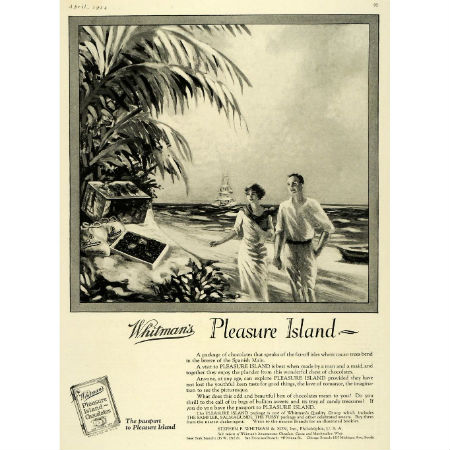

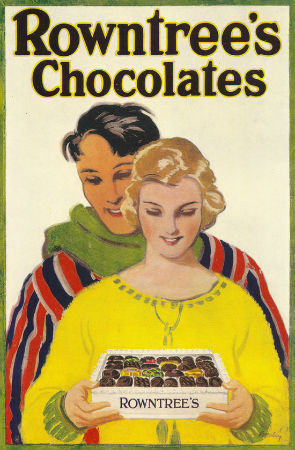

Chocolate’s somewhat taboo but relatively gender-neutral status continued even after industrialization, which, in the words of food historian Barbara Haber, “turned [chocolate] from a bitter and chalky product into the smooth, sweet and sensuous bonbons and bars we eat today.” According to historian Kathleen Banks Nutter’s article “From Romance to PMS: Images of Women and Chocolate in Twentieth-Century America” (which can be read in the anthology Edible Ideologies), early 20th-century advertisements for chocolate often portrayed a woman smiling coyly while offering chocolates to the (implicitly male) viewer rather than indulging herself. One ad’s tag line read, “A visit to Pleasure Island is best when made by a man and a maid, and together they enjoy the plunder from this wonderful chest of chocolates.”

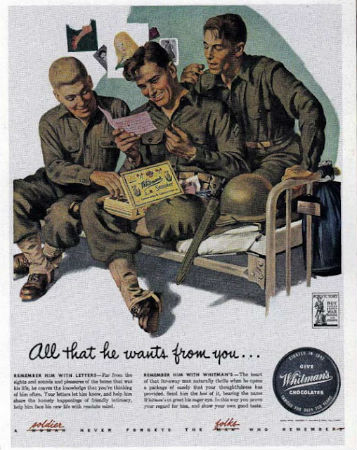

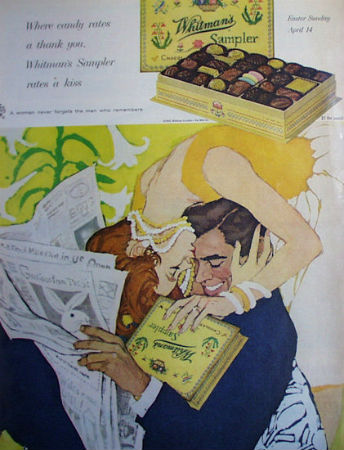

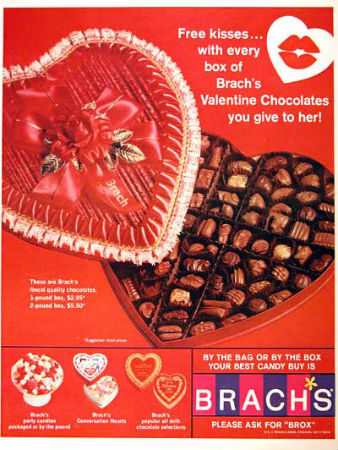

In fact, the modern stereotype of the crazed chocolate-craving woman didn’t appear until the 1960s. According to Nutter, that decade’s casting off of the strict gender roles and sexual prudishness of previous years compelled chocolate advertisers to try a new tack. Advertisers responded to women’s increasing legal gains, financial independence, and social power with pseudo-feminist ads that told women they didn’t need a man so long as they had chocolate. At the same time, advertisements began to sell men on the idea that access to a woman’s sexuality could be bought with chocolate: In 1967, Brach’s ran an ad geared toward men with the slogan, “Free kisses with every box of Brach’s Valentine Chocolates you give to her.”

Today’s chocolate ads, though more explicit, echo the themes of 1960s ads—and age-old sexual double standards. According to Katherine Parkin, an associate professor of history at Monmouth University and the author of Food is Love: Food Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America, contemporary chocolate advertisements don’t need to appeal to men’s desire to indulge themselves, since “Men have more freedom to indulge in all kinds of pleasures.” Instead, chocolate marketers tell men to look at chocolate as an investment: per Parkin, “It’s a pretty inexpensive gift to hope to secure sex from a woman.”

But women still face social stigma for being too sexual, so chocolate advertisers sell them on a different story. Parkin explains, “Our society across the 20th century became more open to women’s sexuality, but … the pressures on women remain to be chaste and available.” Chocolate lets women avoid that pressure, and it’s more socially acceptable for women than other sensual consumables, like alcohol. Mainstream America still isn’t comfortable with the idea that women might actually enjoy sex per se—but it’s more than happy to watch beautiful women feign sexual bliss while biting into a piece of chocolate.