Rap sometimes struggles with a false dichotomy between “realness” and self-conscious artistry that dates back (at least) to the split between 1990s progressive rap groups (A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, etc.) and the gangsta stylists who largely usurped them. At the time, jazz references became a signifier that slotted an artist over on the boho sidelines rather than in the corners-and-clubs–ruling mainstream. With To Pimp a Butterfly in 2015, Kendrick Lamar pulled off the improbable feat of reuniting the salon and the street, with an epic narrative about success and guilt and about black bodies and psyches in crisis, set largely to a new generation of L.A. post-jazz sounds (from Kamasi Washington, Flying Lotus, Thundercat, and other associates of the West Coast Get Down collective). It made the album one of the few consensus rap masterpieces of the decade.

Following up was bound to be a hurdle. But going further in the Butterfly direction (instead of the Pimp one, you might say) would have been an excursion too far from hip-hop’s contemporary center. Lamar is too fierce about his place as his generation’s sharpest contender in the never-ending greatest-rapper debate to step out of the main game. As he reinforced with last month’s one-off single, “The Heart, Part 4,” he’s got rivals to fend off, including Drake, Future, and Big Sean. Just as important, he’s too loyal to Compton, the home turf he fretted about abandoning on TPAB, to commit to a sound too esoteric for most fans’ ears. And, finally, he perhaps felt the time wasn’t right for any indirectness.

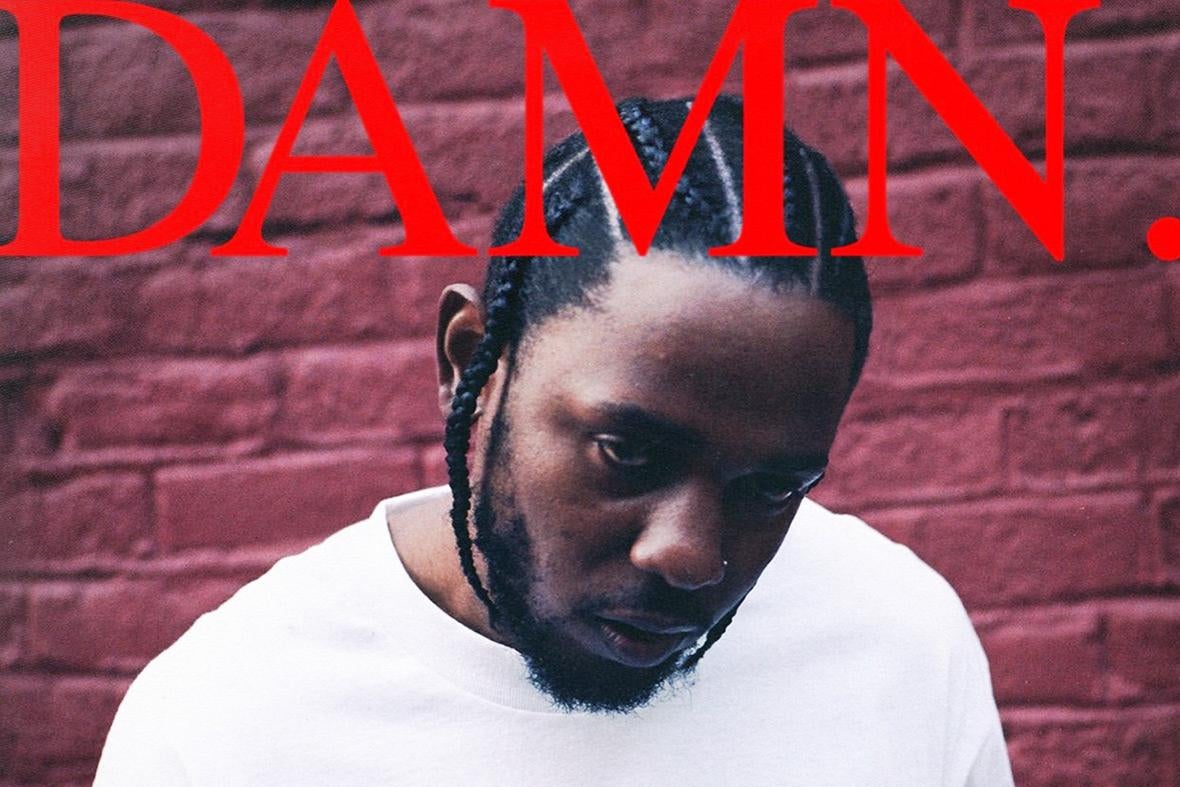

So on Damn (officially styled, along with the song titles, in all caps and with an emphatic period at the end), the album he dropped at the end of last week, the sound palette is stripped back to starker beats, effects, and vocal hooks. Live free-jazz performers and electronic experimenters mostly cede to more commercial banger-makers such as Mike Will Made-It and in-house team member Sounwave; producers’ producers such as the Alchemist and 9th Wonder; and a newer collaborator called Bēkon, formerly known as Danny Keyz. Lamar’s label head Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffith also played a much more active role. Where TPAB drew heavily on the 1990s legacy of California rap as well as older jazz and soul, Damn more often evokes the Dirty South sound whose tendrils extend into most contemporary hip-hop. (However, there are relatively few of the trendy island rhythms and house beats that prevailed, for instance, on Drake’s latest release; Lamar’s not angling for Song of the Summer.) And instead of appearances from more obscure guests like Bilal, there’s a superb feature from Rihanna (rapping, even) on the core-values statement “Loyalty,” and even a (thankfully) subdued one from U2.

So Kendrick the competitor is on full alert here, but Lamar the artist and conceptualist never hits the snooze button either. Damn has the thematic weight and structural intricacy to fit into what’s becoming a historic album run à la mid–1960s Bob Dylan or early–1970s Stevie Wonder, following TPAB and 2012’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D City. Unlike those records, though, Damn is not a cinematic or operatic story cycle. It’s in another mode.

The first track, “Blood,” kicks off with cosmic-choir harmonies, posing the question, “Is it wickedness? … Is it weakness? … You decide …” Musically it calls up the choral sections on 2016 albums by Kanye West and Chance the Rapper that announced rap had a gospel-music revival going on. Characteristically, Lamar carries that impulse to a further extreme, as a true believer and always a tormented moralist: As a whole, Damn really is an extended sermon. It was no coincidence that he dropped it on Good Friday, though not, as the internet instantly convinced itself, because Lamar was going to “rise again” with a whole second album on Easter Sunday. It was because he wanted to testify about sin and redemption, in 14 songs, like the Stations of the Cross.

Throughout Damn, Lamar uses preacher’s tactics, pulling in anecdotes and texts from all kinds of sources and weaving into them repeated phrases and images to insinuate themes and work his way around to his primary message. Reductively I’d describe it as being about the burden of free will—that God has given humanity the ability either to choose virtue or to yield to temptation, in every sphere of life, and most of us screw it up. Which comes with consequences, although as Lamar and his backing vocalists frequently reiterate, “What happens on Earth stays on Earth.”

He opens on “Blood” with what might be described as the parable of a not-so-smart Samaritan, when he stops to help a blind lady on the street and gets shot for his troubles. And he builds to a (literally) killer closer with “Duckworth,” a rapid-fire account of how, decades ago, Lamar’s own father (Duckworth is his surname) used his wits and good graces to narrowly avoid being killed by a then-gangbanging Top Dawg in a Compton fast-food robbery. Without that act of mercy, Lamar speculates, a fatherless boy probably would have succumbed to gang life himself and ended up dead instead of recording albums with his dad’s former would-be murderer. (“Whoever thought the greatest rapper would be from coincidence?”) It’s Lamar’s climactic personal illustration of the ramifications of our moral choices, and one hell of a yarn.

(A lot of fans online have been couching their praise by saying, “If it’s true, that’s an amazing story.” But no, that’s too much “realness” testing. As Lamar puts it across, it’s an amazing story, full stop. Reportedly it did happen, but it would be just as stunning a piece of fiction. And the way Lamar sets it up by seeding previous songs with brief mentions of other family members is more of his adroit sermon-constructing technique.)

Near the end of that song, the sound begins running backwards, as if rewinding, and some music and words from “Blood” start to repeat, returning us to the top of the album and to the top of another cycle: Which choices will you make this time? it implies. Could it all turn out differently?

As always, Lamar is ready and eager to skewer his own failings, as in a face-smacking, spat-out, revenge-murder-spree fantasy on “XXX” (the U2 collaboration), which he caps by murmuring, “All right kids, we’re gonna talk about gun control.” But he’s more self-assured and less tortured here than on TPAB—the tracks placed squarely in the middle are “Pride” and first single “Humble,” as if to admit his vanity is his current greatest vice—and he’s more prepared to lay blame.

That’s what the much-discussed Fox News samples on the first few tracks are about, with clips of conservatives grousing on air about Lamar’s work and hip-hop in general as the true scourge of black America. Lamar isn’t just beefing back, but pointing out how societies as a whole also make choices and shirk their responsibilities.

White America’s self-soothing denial of its role in black pain and oppression is a similar kind of sin, on a larger scale, to the ones he’s illuminating on many other earthly planes, as highlighted by all his blunt, elemental one-word titles such as “Lust,” “Love,” and “Fear.” Tracks like the latter, one of the album’s most heated and penetrating, as well as the equally scathing “DNA,” probe for the root causes of our personal and collective misdeeds, yet they question whether those explanations are just the excuses we make. Like another great inquisitor into American morality, James Baldwin (a nonbeliever, but also schooled in the pulpit), Lamar doesn’t think it’s so simple as whites being genetically rotten, but that majoritarian America projects its own evils onto the marginalized. He sounds that out in “XXX” in a couplet full of thematically apt, internal slant rhymes: “Gang members or terrorists, et cetera, et cetera: / America’s reflections of me—that’s what a mirror does.” (However, Lamar does flirt with more conspiratorial ideas in several places: the notion that black people are the true Israelites, and as God’s actual chosen people, have been singled out for suffering as some kind of a test. Oh, religion, why must your moral insights always come with a catch?)

There are more laid-back, playful sections, too, with fatter, more luscious beats and plenty of clever background sounds and aural allusions. Lamar still speeds and slows his syllables, and rounds and sharpens and lowers and heightens his vocal timbre like one performer voicing an entire cartoon cast. But the tendency on Damn to take more streamlined sonic routes that drive more directly to a point also seems like his response to the pressures of the moment. When To Pimp a Butterfly came out in the late Obama years, it made sense to explore wide spaces for undreamt possibilities and ways of being, their promises and their perils. In 2017, that has become a luxury.

There are only a few direct references to Donald Trump on Damn, but his presence in the background, I think, fuels the whole album’s determination to demand an accounting of how the world can go so wrong. Late in the song “Lust”—which is otherwise about heedless hedonism (perhaps including a groping president’s?)—Lamar looks back on the morning after the election, which generates one of my favorite lyrical and sonic moments on the album. Or rather, partly, not on it. He vividly evokes the common experience that day of disbelief, “still and sad, distraught and mad” talking to neighbors and agreeing on the need to “parade the streets with your voice proudly”—but then comes “time passin’, things change, reverting back to our daily programs, stuck in our ways.” Lamar punctuates and sums that backsliding up with a single word.

Now, on the album’s final version, that word is the song’s title, “lust,” and it’s topped with a wiggly line of electric-guitar feedback. But on the version leaked the day before the official release, it was “drones,” and it was followed by an extended electronic version of that feedback, accompanied by heavy, fearful, and/or lustful breathing. It summoned up every sense of the word drone—a monotonous sustained musical note, a hovering and menacing military technology, and then all of America as buzzing insect workers in an unthinking colony, too often carrying on our assigned roles when we should be rising and resisting the pretender king.

I suppose Lamar and his producers might have changed it in pursuit of more concision and coherence, but I lament it. It perhaps shows one of his (few) artistic faults, a tendency to want to knit things up too tightly, to adhere too strictly to concept. I can analyze why every track on Damn is here, but there are a few (“Element” and “God,” primarily) that to my ears enhance the cycle more than they do the music. Several reports from his collaborators say that there were plenty of hot tracks that went unused (which helped propel the online second-coming rumors this weekend). If he follows the pattern of TPAB, perhaps we’ll get to hear some of those in the future on an EP, in the manner of Untitled, Unmastered.

Then again, perhaps Lamar was right that they would subtract from the whole. No matter, ultimately, because listening to Damn already leaves this listener, at least, wrung out, down to the soul. Once he pimped a butterfly, and now he’s pinned a nation of bees. Here, the realness is the artistry, and vice-versa, and it makes all his rivals seem like slouches by comparison. On every front, then, divine mission accomplished.